Volume 16, Number 6

Christian Dalsgaard and Klaus Thestrup

Centre for Teaching Development and Digital Media, Aarhus University, Denmark

The objective of the paper is to present a pedagogical approach to openness. The paper develops a framework for understanding the pedagogical opportunities of openness in education. Based on the pragmatism of John Dewey and sociocultural learning theory, the paper defines openness in education as a matter of engaging educational activities in sociocultural practices of a surrounding society. Openness is not only a matter of opening up the existing, but of developing new educational practices that interact with society. The paper outlines three pedagogical dimensions of openness: transparency, communication, and engagement. Transparency relates to the opening up of student work, thoughts, activities, and products in order to provide students with insight into each other’s activities. Communication aims at establishing interaction between educational activities of an institution and surrounding practices. Openness as joint engagement in the world aims at establishing interdependent collaborative relationships between educational institutions and external practices. To achieve these dimensions of openness, educational activities need to change and move beyond the course as the main format for openness. With examples from a university case, the paper discusses how alternative pedagogical formats and educational technologies can support the three dimensions of openness.

Keywords: Openness, Open Education, Online Education, MOOCs, OER, Transparency, Communication, Engagement.

The starting point for the paper is the question: What is the objective of openness in education? And more specifically: What are the pedagogical opportunities of openness? Open or openness is and has been a central concept within research and discussions on online education in the last 10-15 years. The open educational resources (OER) movement has paved the way for the concept of openness, which today is most visible in ongoing debates as the first O in MOOCs - Massive Open Online Courses. Historically, the most central objective of open education has been to offer education for students that for different reasons do not have access to the traditional educational system (McAndrew, 2010; Littlejohn & Pegler, 2014). Thus, the objective behind open education is not pedagogical, but is mainly derived from education policy. In this paper, we call for an increased focus on the pedagogical opportunities of openness in education.

The original ideas of open universities and distance education also constitute the main motivation for the open education movement today; i.e. to educate people with no or limited access to the traditional educational system. However, since the coining of Open Educational Resources (OER) in 2002 (UNESCO, 2002), the open education movement has widened the concept of open towards education for all. The main rationale behind the OER movement is to utilise digital media to provide free and open access to educational resources that can be copied, distributed, and reused worldwide (Caswell, Henson, Jensen and Wiley, 2008; Friesen, 2009;). Thus, OER mirror and extend the original intentions of open education, and consequently, a key focus of the OER movement is sharing, accessibility, and reuse (Windle, Wharrad, McCormick, Laverty and Taylor, 2010; Pegler, 2012). Apart from influencing education policies, the OER movement has contributed massively to developments within digital repositories and also within development of metadata standards and open licensing (Hylén, 2006). Like OER, the perspective of MOOCs is to provide education for all - in the format of courses, not (only) resources. Although education for all is a key objective for MOOCs, as well as OER, the debate revolving around MOOCs has somewhat distorted the discussions on the concept of openness. MOOCs are, arguably, one of the most interesting initiatives within open education, but it is evident from the massive criticism of MOOCs that they are not the sole answer to the challenges of open education, and they do not fulfill all the potentials of online education. de Langen and van den Bosch (2013) argue that both MOOCs and OER are primarily a supplement, rather than a competitor, to regular forms of education for degree-searching students. However, experiences from current MOOC experiments can be used as a catalyst for exploring new opportunities of open online education. In a white paper on MOOCs, Yuan, Powell and Olivier (2014) place emphasis on the opportunities arising from MOOC experiences and they highlight a number of themes relevant to higher education. One of the themes is openness, and Yuan, Powell and Olivier (2014) argue that MOOCs provide new approaches to online learning, especially learning that goes beyond institutional borders. A second theme is pedagogic opportunities, where MOOCs have challenged the traditional roles of teachers and students. Following Yuan, Powell and Olivier (2014), this paper will use the MOOC experiments as a stepping stone for a more broad discussion of the new opportunities of openness in education.

As research on MOOCs clearly conclude, there are many challenges to opening up education to a large audience. Low completion rates have been highlighted as a central challenge of open online courses, in particular MOOCs (Chen, 2014; Daniel, 2012; Kizilcec, Piech and Schneider, 2013; Clow, 2013). According to a study in Jordan (2014), an average of 43,000 students enrolls in a MOOC, and only 6.5% complete the course. The longer the course, the smaller the completion rate (Jordan, 2014). OER are naturally not confronted with issues of dropout rates, but according to McAndrew, Farrow, Elliott-Cirigottis and Law (2012), there is not much evidence of the extent of use and reuse of OER (McAndrew et al., 2012). In that respect, OER face the same challenge as MOOCs of providing evidence of reaching new target groups.

The MOOC solution to open education has also been criticized for problematic business models (Daniel, 2012) and for an increased commodification of education (Dolan, 2014). OER and MOOCs face similar challenges of establishing business models for sustainable development and maintenance (Friesen, 2009; Wiley, 2007; Downes, 2007). As de Langen (2013) also writes, investments in OER have decreased in recent years. Most critically to the perspective of this paper, also the pedagogical quality of OER and MOOCs has been questioned. When discussing MOOC pedagogy, it is relevant to distinguish between different types of MOOCs, mainly between xMOOCs and cMOOC. The latter represent the early MOOCs that were explicitly based on connectivism, whereas the term xMOOC is used for MOOCs provided through Coursera, EdX and similar (Siemens, 2013; Daniel, 2014). The pedagogical criticism is mainly directed at xMOOCs and primarily targets the dominance of one-way video lectures, isolation of the individual learners, and ineffective assessment (Chen, 2014; Daniel, 2012; Dolan, 2014). Daniel (2012) points out that xMOOCs do not even employ a new pedagogy, but rather make use of online and distance learning techniques that date back at least 40 years.

In that sense, there is much that is not new and innovative of recent xMOOCs. However, what is new in MOOCs is the exploration and experimentation with education made available to all – in the form of online courses. However, from the point of view of opening up education for everybody, a central critique of MOOCs and OER is that they disregard the complexity of the target groups that they address. Jordan (2014) states that MOOCs are in fact not for everybody, but primarily favour the educationally privileged, whereas it is difficult for MOOCs to reach disadvantaged students. For example, the majority of Coursera students are at least on an undergraduate degree level (Jordan, 2014). Similarly, Dolan (2014) criticizes the “one size fits all” approach of most MOOCs. All enrolled students are supposed to follow the same course, hand in the same assignments, and go through the same activities.

A study of subpopulations of learners in MOOCs by Kizilcec, Piech and Schneider (2013) clearly shows that one size does not fit all kinds of learners. This study (Kizilcec et al., 2013) also provides an important contribution to the criticism concerning high dropout rates. Kizilcec, Piech and Schneider (2013) identify four prototypical types of learner engagement in MOOCs. They distinguish between learners completing, auditing, disengaging, and sampling. Especially the auditing group is interesting. None of the auditing learners completed the course – and will be part of the “negative” percentage of dropouts – but they expressed a high degree of satisfaction, and the courses were useful to them. Also disengaging and sampling learners are relevant to understand the complexity of different ways of using open education. It may not necessarily be the fault of the course that these learners are disengaged and only sample from the course. These groups of learners are not necessarily interested in following an entire course, but have other needs for input and resources that they found in the MOOCs.

A central question arising from the studies of Kizilcec, Piech and Schneider (2013) is how open education can be designed in order to support different target groups, such as external partners or "non-students" of the surrounding society. This paper will contribute to this discussion. We wish to go back to the fundamental objectives of open education and discuss them from a pedagogical perspective. In that sense, the paper is not specifically about OER or MOOCs, but more broadly concerns how open educational methods can develop the pedagogical quality of education and through this qualify the discussions on OER and MOOCs. Returning to the question “What is the objective of openness in education?”, the paper will approach the concept of openness from a pedagogical perspective and provide a framework for understanding the pedagogical opportunities of openness in education. The purpose of the paper is to explore different dimensions of openness in (higher) online education.

Behind opening up education are different motives. One is a political, ideological motive concerning open and free education for all, another is public relations of institutions. Several other motives could be found, and every motive will result in very different conceptions of openness. As stated above, this paper will explore pedagogical motives for openness in education. Although openness is primarily related to online education, it is not a new concept or thought within educational and pedagogical thinking. The technological frame of online education has coupled openness with accessibility to content and courses. To explore pedagogical motives for openness, the paper will draw on the ideas and visions of John Dewey from the beginning of the 20th century. Dewey (1907) argued – in his own terminology – for opening up the school system, and his thoughts are highly relevant in today’s discussions on openness. Taking Dewey (1907) as a starting point, a central objective of openness is to connect education to the life and work of the surrounding society.

“From the standpoint of the child, the great waste in the school comes from his inability to utilize the experiences he gets outside the school in any complete and free way within the school itself; while, on the other hand, he is unable to apply in daily life what he is learning at school. That is the isolation of the school -- its isolation from life.” (Dewey, 1907)

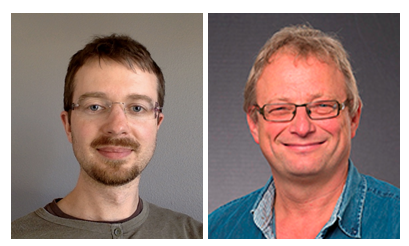

Dewey (1907) argues that the school should be made a form of active community life, rather than “a place set apart in which to learn lessons.” In that sense, educational institutions should themselves be viewed as communities that engage in interaction with other parts of society. Dewey (1907) argued for a development in schools “of a spirit of social cooperation and community life.” To support this understanding of the school in society, Dewey put forth illustrative proposals for building a school that is not isolated from, but rather in constant interaction with society (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dewey’s model of school in interaction with society (adapted from Dewey, 1907).

Figure 1 shows Dewey’s illustration of how the school should interact with different areas of society. One of the dimensions of interaction with society is that of “business,” which can provide an example of the kind of interaction or openness that Dewey (1907) envisioned for educational institutions.

“Though there should be organic connection between the school and business life, it is not meant that the school is to prepare the child for any particular business, but that there should be a natural connection of the everyday life of the child with the business environment about him ...” (Dewey, 1907)

Dewey’s (1907) image of openness is to connect activities of the educational institution to that of the surrounding society. Today, the school is not necessarily a physical building as it was in the first half of the 20th century. Schools of today can very easily communicate with the surrounding society by means of digital technologies, which from a Deweyan perspective provides new opportunities for relations between school and society. Digital technologies are mobile, ubiquitous, and provide opportunities for exchange, inspiration, and production of content across time and space.

A point that can be drawn from Dewey’s thoughts on the role of school in society is that opening up courses and making them available to everyone is not the same as interaction with and participation in society. From the thoughts of Dewey, this paper explores the opportunities for opening up education as such towards society, rather than opening up different courses. The traditional approach to open education is to offer courses to a larger group of students. However, the target group is still students, which is evident in the focus on completion rates (Chen, 2014; Daniel, 2012) and from the fact that most MOOC participants are educationally privileged (Jordan, 2014). But open education can also interact with a surrounding society and consequently reach new target groups – that is, “non-students” and people that are not familiar with higher education or a more traditional academic way of thinking and working.

Students taking part in open education are often active in their own work life or local community life and this constitutes a huge potential to both act in and reflect upon when solving tasks in an educational system. Basically they have the capability to be and become reflective practitioners (Schön, 1983) in its most demanding sense. They can become part of educational and societal processes, where the theoretical approach challenges existing practical methods and principles and vice versa. The result can in principle both be fundamental changes in the practical approach and being an active part of academic discussions on theoretical developments.

The pedagogical approach behind the perspective on openness presented in this paper is rooted in the pragmatism of Dewey (1916) and further draws on sociocultural theory. Central to these approaches is the emphasis on the importance of actions and practice for learning. Wertsch (1994) defines a sociocultural approach: “At the most general level a sociocultural approach concerns the ways in which human action, including mental action (e.g., reasoning, remembering), is inherently linked to the cultural, institutional, and historical settings in which it occurs.” (p. 203). The sociocultural approach has roots in pragmatism (Dewey, 1916) and cultural historical activity theory (Vygotsky, 1978; Leont’ev, 1978), and also draws parallels to the theory of situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991). A fundamental starting point for learning according to Dewey (1916) is aims and purposes of individuals. Individuals are directed at goals and act with purposes that frame the context for learning. In that sense, learning stems from the context of the individual. However, social relations are also central to a sociocultural approach. Lave and Wenger (1991) and Brown, Collins, & Duguid (1989) argue that learning is always situated within a social practice. The actions of the individual are placed within a sociocultural practice, which includes actions of other people. In that sense, actions are never strictly individual, because they always relate to actions of others (Leont’ev, 1978). As a consequence, different forms of interaction between individuals become central to learning.

To connect the sociocultural approach to Dewey’s thoughts on open institutions, openness in education can be defined as a matter of engaging educational activities in sociocultural practices of a surrounding society. On one hand, institutions should provide students with access to activities of others and to sociocultural practices outside the institution. On the other hand, educational institutions should aim at developing relations between themselves and relevant surrounding sociocultural practices. The latter includes a pedagogical potential of open education to contribute to aims and purposes of “non-students” in a surrounding society. Education of these “non-students” should not attempt to construct new aims and purposes originating from an institutional course setting, but should facilitate interactions that benefit the context of the individuals outside the institution. From that perspective, a course is not the right open format. In the case presented in the paper, we will discuss other kinds of open formats for interaction with a surrounding society.

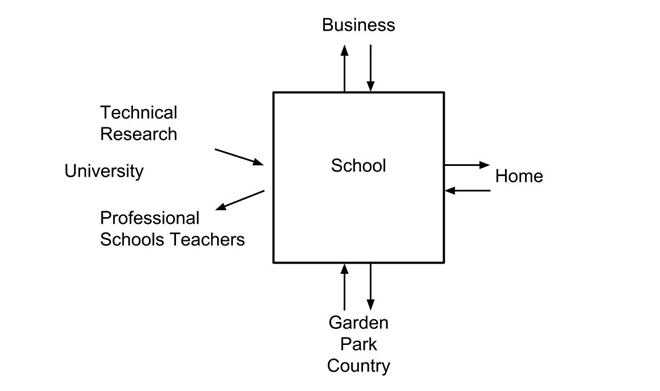

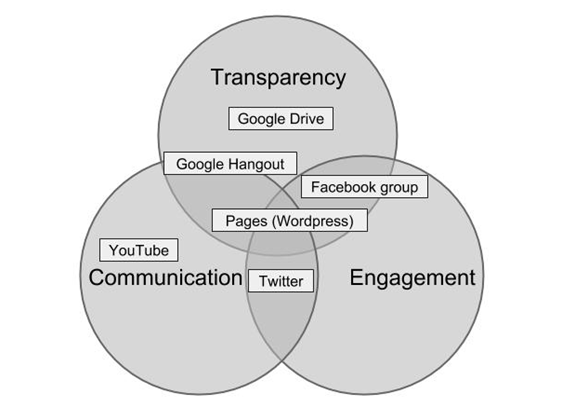

Whereas Dewey (1907) primarily focuses on the exchange from the outside world towards educational institutions, the approach to openness presented below also encompasses interaction from the institution towards the outside world. The paper will make a distinction between three dimensions of openness that serve different purposes: openness as transparency, communication, and engagement. Together, the three dimensions provide an understanding of pedagogical opportunities of openness. The model in figure 2 shows that the three dimensions of openness are non-hierarchal and overlapping.

Figure 2. Three dimensions of openness.

The first dimension of openness relates to supporting transparency between students. This is in line with Dalsgaard and Paulsen (2009) who argue that transparency is a kind of communication where students gain insight into the activities of each other. Transparency differs from collaboration and discussion in the sense that transparency might only be a matter of students viewing the activities and work of each other. Thus, transparency could be a form of sharing of discussions, texts, and products between groups or individuals that are not collaborating with each other. This dimension of openness relates to making student work available between students. From a sociocultural perspective, the pedagogical potential of transparency relates to students’ reflection on their own work and activities in relation to that of others (Dalsgaard and Paulsen, 2009). Transparency is a matter of opening up activities to fellow students to provide an insight into related activities. This dimension calls for opening up the work, thoughts, activities, and products of students. In that sense, this is first of all an internal openness between students. However, this openness can potentially move beyond the specific course, but it is important to note that this form of openness has students as a target group, but it can potentially be students in other courses or enrolled at other universities. This dimension of openness is relevant to what Dron and Anderson (2014) term “set.” A set is a social form “made up of people with shared attributes” (Dron and Anderson, 2014), which could be a shared interest in a topic. From the sociocultural perspective, people within sets share aims or purposes or even a sociocultural practice, which means that their activities are likely to be relevant to each other. The objective of this kind of openness is to provide students with input and inspiration from fellow students. This means that the open format is not a course, but isolated work of students.

The second dimension relates to openness as communication between students and the outside world. In other words the objective is to establish communication between educational activities of an institutional course and surrounding sociocultural practices. Transparency is the starting point for this kind of interaction, the difference being that the target group has changed. From the point of view of the institution, this form of openness is made possible by opening up educational activities, discussions, and products. However, the objective is not to provide access for external partners to a course or existing course activities, but rather to communicate to related sociocultural practices that do not consist of students enrolled in a course. Compared to transparency, this implies different open formats for communication targeted at the surrounding society of "non-students." The target group for this open format is people who share a field of interest (Dalsgaard, 2006). This dimension of openness can be viewed as a kind of presentation or dissemination of educational activities emanating from a course. The aim is that external partners such as students from other educational programmes, companies, or non-profit organizations can follow and get insight into the subject matter of the courses. In that sense, this dimension of openness aims at reaching new target groups by providing different formats than the ones aiming at enrolled students. This can be seen as an attempt to overcome the “one size fits all” tendencies of MOOCs (Dolan, 2014) and directly target for instance the auditing, disengaging, and sampling types of students (Kizilcec, Piech and Schneider, 2013). This kind of communication could take on the form of network communication (Dron and Anderson, 2007; 2014), which means that the shared educational activities and products can potentially reach people and practices unknown to course participants.

The dimension of openness as communication can also be viewed from the point of view of the practices outside educational institutions. From the perspective of the outside world, external partners can also attempt to communicate their information and practices, thus making it possible for institutions to connect. This would comply with Dewey’s (1907) ideas about connecting educational institutions and society. Similar to transparency, this dimension of openness does not necessarily entail two-way communication or collaboration between institution and external partners. It can involve two-way communication and discussions between institution and external partners, but it can also be limited to one-way communication targeted at specific groups with the objective of providing input and inspiration. From the point of view of educational institutions, the objective could be dissemination of current discussions within the academic field, whereas external partners could pose questions or provide real world challenges to educational institutions.

The third dimension of openness aims at establishing interdependent relationships between educational institutions and external practices. The objective is that students and teachers become partners in discovering and solving actual problems together with other partners that might be other institutions, companies, or non-profit organisations. Transparency is now transformed into actual communication, when there is an ongoing dialogue between different participants in a project. Communication turns into engagement through a common task, which becomes the focal point for mutual engagement between educational institution and external partners. Consequently, the open format of this dimension is not a course, but rather takes the form of a collaborative project or task.

The three dimensions of openness can co-exist at any given time or they can be established according to the actual educational situation and possibilities.

To discuss the three dimensions of openness, we use examples from the educational programme ICT-based Educational Design (Centre for Teaching Development and Digital Media, Aarhus University, Denmark), which was redesigned in 2012 from a traditional campus-based to a mainly online programme. A central focus point of the redesign was to open up the educational programme to the outside world.

Its purpose is to enable the students to analyse and design ICT-based educational processes in both formal and informal contexts such as schools, kindergartens, and in principle anywhere learning can take place. The enrolled students are often experienced teachers and pedagogues with work experience and have to a large extent used different kinds of technologies prior to enrollment. The students are spread over the country, but more and more students also attend the programme even though they live part time outside the country. Each year around 30 students are enrolled in the educational programme.

The descriptions below are based on our ongoing development of the programme. Throughout the study, we have continuously experimented with new educational formats and technologies. After each module we have gathered data from student communication, writings, and productions, and we have used student evaluations (both questionnaires and oral evaluations) to understand how the students reacted to our changes. We have employed an increasing number of technologies in order to support the different kinds of openness. The presented study is not meant to replace MOOCs, but the intention is to contribute to the ongoing debates on MOOCs, OER, and other kinds of online education. We consider our work as a range of pilot studies preparing for a larger and more substantial way of identifying, supporting and debating openness in education. The current pilot studies form the background of future qualitative research in the field.

As these students are practitioners enrolling in an educational programme at an academic level, Schön's reflective practitioner is at stake as a way of understanding the way of teaching and constructing form and content of the course (Schön, 1987). The practitioner reflects in action, but through reflecting upon action, the practitioner can change the very principles and patterns of action. Thus, action and reflection have to be closely and constantly connected to make the student a reflective practitioner during the programme and of course after the finished education. In addition the students are presented for entrepreneurship as a way to carry out projects, where the goal of the project is based on the development in the process (Sarasvathy, 2001). The students work with learning theories with the objective of understanding how education (including their own) takes place within a global knowledge and media society and therefore is in a process of comprehensive change from knowing what to learn in advance in an industrial society to be able to learn in a knowledge society (Low, 2013; Robinson, 2010). A central perspective of the educational programme is to view education as experimenting together in communities (Thestrup, 2013; Thestrup, forthcoming). Students are told that they are part of the same process and that the educational programme itself is experimenting with how to teach and learn.

In the transition to online education, the objective has been to open up the educational programme and make activities and resources available online to students within the course and also to a larger public. The students themselves only meet face to face with the teacher on seminars once or twice every semester. The different courses in the programme instead use different platforms to communicate and produce together. Students work in groups and use Google Hangout to communicate, and Google Drive to write and produce texts and store video together. Google Hangout is also used when the teacher wants to talk together with all students at the same time and decide on what to do next. YouTube is used to publish videos on specific topics. The programme also employs a blogging platform called Pages (developed by Centre for Teaching Development and Digital Media, Aarhus University) based on Wordpress and Buddypress. Within the platform each group has a blog, where they on a weekly basis are asked to post videos, photos, links, and texts on relevant topics, and where they comment on each other’s posts. Meetings, discussions, and lectures are on an increasing level being recorded and broadcasted on Google Hangout on Air. Facebook groups by both teachers and students are used for ongoing inspiration, discussions, and notifications. The actual software used can change but the intention is to establish and integrate the three dimensions of openness. For instance, the Pages platform is open for anyone to have a look or to comment (http://pages-tdm.au.dk).

The case is based on the two courses Learning & Context (10 ECTS) and Learning Theories and Technology (20 ECTS). These courses are both placed at the first semester of the educational programme. Within both courses, students are asked to construct and analyze their own projects that they try out in different contexts. Students are typically divided in 7-8 groups. For each course, the groups are given around 6-8 assignments to solve. Each course then results in approximately 60 blogposts containing video, links, and text. Further, all post are commented by teachers and students somewhere between two and five times. That amounts to 120-300 comments in total. The students also meet with the teacher approximately once a week on Google Hangout. The teacher writes comments in the Facebook group 2-3 times a week. Finally, the Learning Management System, Blackboard, is used to give assignments, and to provide lesson plans, and bibliographies to establish an overview of deadlines and course descriptions.

First of all, we have employed the transparency dimension by establishing an internal openness where students share Google Documents not only in groups but with everybody. This means that almost all student work is made available to everyone within the course, including student assignments. It is by no means a trivial thing to ask students to share their work with fellow students. We have had few experiences with reluctant students, but there is no doubt that much effort should be put into the establishment of a culture of openness among students. This is not necessarily something that students are used to or comfortable with.

The blogging platform was developed in 2012 as part of a comprehensive attempt to design a process, where the students started to build a blogging community that made student and teacher activities as visible as possible to everybody involved. Students can see and comment on the work of other students. The teacher can do the same, and what he or she might comment is also available to all students. This transparency is a means to establish an ongoing learning process, where students can sketch out ideas and opinions, be in doubt, discuss theory and practise, explain and convey. The blogging community is a transparent feedback system, where everybody is activated. The teacher is establishing a professional and internal relation between teacher and students on the actual subjects involved. This dimension is suited for underlining a processual understanding of learning and where the establishing of a new practice is the very center. There is literally something to talk about in the field in question because something it is being tried out simultaneously. There is something to learn from the teacher and the other students.

To make the transparency usable and productive, the students are asked to write and film together. They not only comment on each other, they also produce statements that explicitly include both explanations and questions on theory and practice. They show what they think, what they do and what they are in doubt about. They are also asked to use different visual expressions and different apps to deliberately experiment with how to communicate. Here something is said that matters – even the questions. This approach to a transparent form of openness aims at facilitating communication, discussion, and exchange between students, and ultimately to construct a community among students (Thestrup, 2013).

Within the communication dimension the students actively involve people outside the course in the tasks they have to solve. To show this dimension of openness, students in their groups are asked to make Mindmaps that demonstrate the learning resources for both each person and for the group. In this network of persons and places they are asked to look into both formal and informal contexts. It might be an uncle who knows something about a certain topic or it might be a teacher. They are also asked to create or take part in new networks through for instance Twitter and Facebook. The blogs are in themselves possible tools of communication connecting with a world outside of the course. To show this, the students have been asked to invite someone from outside the course to comment on the blog posts. Those invited have been experts on communication on the actual content and so the comments have been on both areas. The students have met persons who might simply disagree with them or know something the students have not thought of. This communication through social media is an ongoing process but results and examples from these blogs are also presented on a special homepage meant to show what ICT-based Educational Design is about (http://pages-tdm.au.dk/omitdd/cases3/).

A point to be drawn from our experiments with both the transparency and communication dimensions of openness is that different formats are necessary for the two dimensions. In 2012, students also wrote blog posts that were intended to support both internal transparency and external communication. However, it became evident that it was necessary to communicate differently to the external world. The early blog posts were in the form of written assignments and required prior knowledge of the subject matter. As a consequence, the blogs are now more and more being used for posts in a more journalistic format that target a broader public without sacrificing academic argument or scientific method.

The engagement dimension of openness can be exemplified by a project that took place in the Fall 2014 during the course Learning Theories and Technology. The main library in Aarhus is moving to another much larger building Dokk1 (Pier1) and is transformed into to a mediaspace that is a mix of books and digital media, and an open and accessible learning environment supporting both democracy and community (www.urbanmediaspace.dk). The request from the library was to give examples of ways to combine digital spaces and the library with the outside world using communication technologies. The project was one in a long row of experiments at the library on how the future library should be. To construct these experiments the students had to find users of the library and ask them what their needs and dreams about using the library were. They had to talk to a team coordinator who was part of the preparations for new activities at the new library. Also they had to come up with some examples that the users might use, and demonstrate this use at the library with actual users.

One group of students invited families with children that were dyslexic and the headmaster and some young people from a school that had this problem as their special focus. These people discussed, exchanged ideas, and apps that could support the children and youngsters. Some of the invited participants stayed at the library and used digital media to communicate with participants at a different venue in a different part of the country. Another group established a workplace on toy hacking with children. Here the children took apart old toys and made new toys out of it. Again another group of children were staying at their own school but had the possibility to be in contact with the children at the library through digital media. The students in the different groups later used their experiences during examination, where they as reflective practitioners with an entrepreneurial mindset were urged to combine theory and practice and present new ICT-based learning designs inspired by the ones for the library.

The three dimensions transparency, communication, and engagement do exist simultaneously in the project with the main library. The students communicated internally in the groups and between the groups using the blogging community and the Facebook group. They presented and commented on blog posts with video and texts to each other. They also in the process communicated with the team coordinator at the library, the different user groups they had contacted, and others who might know something about the unsolved challenges ahead. At the library they even met new users who came to the library and joined their experiments. During these activities they were in contact with the teachers, who guided them in the process. The students and the teachers were working internally and externally at the same time.

The educational programme is opened towards society for the benefit of both students and society. In principle outside people, for instance other students, can follow the process or even join it. External partners in projects can get smaller or bigger solutions to challenges they are facing. Inspiration to do so can both go from an institution like the university towards society or from society towards the institutions. The teacher role tends to be more of a project manager dealing with a challenge than only a lecturer of a subject. The student role also tends to be more of the project manager facing a problem than just receiving and discussing information already defined by the teacher. Communication between the two is not one-way but can unfold as a dialogue.

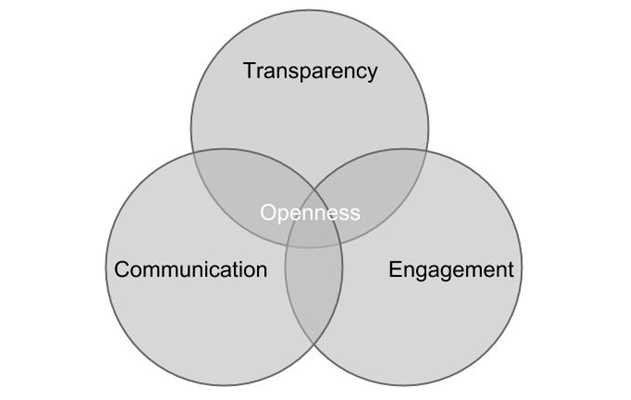

In order to implement the three dimensions of openness, technologies play a key role. Since the students in the case are spread out over the country, communication and production technologies are a necessity. Any technology has to be framed as an educational technology fit for openness. Figure 3 illustrates how different educational technologies were used in the case to support the different dimensions of openness.

Figure 3. Educational technologies supporting the three dimensions of openness in the case.

Google Drive has been the basic technology for establishing an internal transparency between students. Similarly, Facebook groups can support a transparent and open culture within a course, but as demonstrated in the case it has also supported engagement in the form of collaborative projects between students and external partners. In the case, Google Hangout was primarily used for internal transparency and partly for external communication. Everyone can see each other, talk together and share documents during the meeting. The Pages blogging platform was utilised to support all three dimensions. It supported internal transparency through student blogs, which at the same time served as communication to the outside world. Also, external partners were engaged in blog discussions with students and teachers. The intention of YouTube channels was to extend communication beyond the course to the outside world. Texts and videos can inform others and evoke comments and discussions. In the presented case, Twitter was primarily used for external communication and engagement. However, Twitter has the potential to support all three dimensions of openness. It can serve transparency between students, but the primary potential relate to the network communication of Twitter, which can reach new target groups; it is a way to get in touch, get information on where to look for something and for minor discussions.

The mentioned tools are not the only ones used within the educational programme, but the other tools do not serve a function in relation to the three dimensions of openness. For instance, Blackboard is used as a basic course management system that secures that the students at all times are informed on tasks, decisions, and exams. This could also be done through other systems like Google Drive, but the important thing is that this happens and in a legal way.

The point is that the chosen software constitute elements in a coherent system that makes transparency, communication, and engagement possible. It is a question of deciding how to use what part of a communication and production technologies for what purpose together with whom, rather than trying to find software, that only covers one aspect of openness as a technology. One could in an actual design of learning processes use a given software in another way to cover another area of openness than stated in Figure 3. For instance, Google Hangout can be used for transparency to ensure that everybody involved has a possibility to know what everybody else is doing, for communication with external partners and for increasing the engagement with solving challenges in the society that concern these external partners. It comes down to pedagogy and a thinking of education that frames a certain use of different technologies.

Through the three dimensions of openness, conditions are in place to establish a sociocultural connection between education and society. Dewey's pragmatic vision from 1907 scribbled on a blackboard long before the existence of digital media can be enhanced through the different online communication and co-production possibilities. The two examples of students engaging with dyslexic students and children who tried to hack their own toys at a public library point at learning processes involving both students, and in this case children, that can take place in more informal surroundings and possibly connect to experiences and experiments in lived life.

The paper has brought forth arguments based in sociocultural theory that the main pedagogical potential of openness is to engage educational activities in sociocultural practices of a surrounding society. This implies a change in the ways that educational institutions conceive of their output and their target groups. The course as the main open format, as it is the case in MOOCs, is not able to target a broader public of “non-students” that can potentially be reached by opening up educational activities. Instead, this requires that the educational activities of the institution change and adapt to activities of a surrounding society. The paper has explored pedagogical potentials of openness and presented the three dimensions transparency, communication, and engagement. Transparency relates to the opening up of student work, thoughts, activities, and products in order to provide fellow students with insight into each other’s activities. The objective of the second dimension is to establish communication between educational activities of an institutional course and surrounding sociocultural practices. A key target group for this dimension of openness is “non-students” who share a field of interest with the subject matter of the course. Finally, openness as joint engagement in the world aims at establishing interdependent collaborative relationships between educational institutions and external practices.

Educational technologies play a key role in enabling the three outlined dimensions of openness in education. The presented case of the paper shows that there is no one-to-one relationship between dimensions and technologies, but that the three dimensions can be achieved by a combination of technologies that play different roles. Within the presented case, Google Drive and Google Hangout primarily provided support for internal transparency, whereas an open blogging platform in a combination with Facebook groups, Twitter, and YouTube extended the transparency and developed a foundation for communication and engagement with the outside world.

The primary historical objective of open education has not been of a pedagogical nature, but has been a political objective of providing education for students with limited access to institutions. From the perspective of this objective, the pedagogical methods of open, online, and distance learning can be viewed as “the next best thing,” because of the initial restraints of reaching a broader audience who are unable to attend a traditional class. In that sense, the often highlighted potential of Open and Distance Learning (ODL) to reach alternative target groups can overshadow the unique pedagogical opportunities of openness. Based on the pedagogical approach to openness presented in this paper, we call for an increased focus on the pedagogical advantages and opportunities of open, online education.

The implications of the developed framework for openness for ODL theory are to further develop a pedagogical approach that conceptualises the unique pedagogical dimensions of openness. For ODL practice, the challenge of the framework is to develop new pedagogical methods that enable transparency, communication, and engagement. This is not done only by opening up resources or courses (like OER or MOOCs), but requires new educational activities that move beyond courses and enrolled students, and that are able to communicate and engage with the surrounding society - both locally and internationally.

The paper and the case has demonstrated that the framework of the three dimensions of openness can be utilised to analyse and design educational activities and technologies connected to sociocultural theory and Dewey's pragmatism. Future studies and educational development will show the refinement of the model and the possible impact on online education in all its forms.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A. & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), p. 32-42.

Caswell, T., Henson, S., Jensen, M., & Wiley, D. (2008). Open content and open educational resources: Enabling universal education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(1).

Chen, Y. (2014). Investigating MOOCs through blog mining. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2).

Clow, D. (2013, April). MOOCs and the funnel of participation. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 185-189). ACM.

Dalsgaard, C. (2006). Social software: E-learning beyond learning management systems. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, 2.

Dalsgaard, C., & Paulsen, M. F. (2009). Transparency in cooperative online education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(3).

Daniel, J. (2012). Making sense of MOOCs: Musings in a maze of myth, paradox and possibility. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 3, Art-18.

de Langen, F. H. T. (2013). Strategies for sustainable business models for open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(2), 53-66.

de Langen, F., & van den Bosch, H. (2013). Massive open online courses: Disruptive innovations or disturbing inventions?. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 28(3), 216-226.

Dewey, J. (1907). The school and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: The Free Press.

Dolan, V. L. (2014). Massive online obsessive compulsion: What are they saying out there about the latest phenomenon in higher education? The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2).

Downes, S. (2007). Models for sustainable open educational resources. National Research Council Canada (2006).

Dron, J., & Anderson, T. (2007). Collectives, networks and groups in social software for e-Learning. In World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education, 1, pp. 2460-2467.

Dron, J., & Anderson, T. (2014). Teaching crowds: Social media and distance learning. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press.

Friesen, N. (2009). Open educational resources: New possibilities for change and sustainability. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 10(5).

Hylén, J. (2006). Open educational resources: Opportunities and challenges. Proceedings of Open Education, 49-63.

Jordan, K. (2014). Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(1).

Kizilcec, R. F., Piech, C., & Schneider, E. (2013). Deconstructing disengagement: analyzing learner subpopulations in massive open online courses. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (pp. 170-179). ACM.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Moscow: Progress.

Littlejohn, A and Pegler, C. (2014). Reusing Resources: Open for Learning. Journal of Interactive Media in Education,1(2). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/2014-02

Low, E. L. (2013). Learning in and for the 21st Century. The Office of Education Research. NIE/NTU, Singapore.

McAndrew, P. (2010). Defining openness: updating the concept of" open" for a connected world. Journal of interactive Media in Education, 2, Art-10.

McAndrew, P., Farrow, R., Elliott-Cirigottis, G., & Law, P. (2012). Learning the lessons of openness. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2, Art-10.

Pegler, C. (2012). Herzberg, hygiene and the motivation to reuse: Towards a three-factor theory to explain motivation to share and use OER. Journal of Interactive Media in Education 2012, 1(4), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/2012-04

Robinson, K. (2010). Changing paragdigms: RSAnimate, RSA Events, Cognitivemedia, lokaliseret 15.01.2015 på https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U

Sarasvathy, S. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243-263.

Schön, D. A: (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Location: Jossey-Bass Publishers

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic books.

Siemens, G. (2013). Massive Open Online Courses: Innovation in Education. Open Educational Resources: Innovation, Research and Practice, 5.

Thestrup, K. (2013). Det eksperimenterende fællesskab: Medieleg i en pædagogisk kontekst [The experimenting community: Media play in a pedagogical context]. Doctoral dissertation, Aarhus University, Denmark.

Thestrup, K. (forthcoming). A Framework for the future. When kindergartens go on-line. In Kupiainen, R. og Kotilainen, S. (ed.). Media Education Futures (working title). Nordicom Review.

UNESCO (2002). Forum on the impact of Open Courseware for higher education in developing countries final report. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001285/128515e.pdf.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. London: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1994). The primacy of mediated action in sociocultural studies. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 1(4), p. 202-208.

Wiley, D. (2007). On the sustainability of open educational resource initiatives in higher education. COSL/USU Paper commissioned by the OECD's Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) for the project on Open Educational Resources

Windle, R.J., Wharrad, H, McCormick, D, Laverty, H & Taylor, M.G. (2010). Sharing and reuse in OER: experiences gained from open reusable learning objects in health. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(4). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/2010-4

Yuan, L., Powell, S., & Olivier, B. (2014). Beyond MOOCs: Sustainable online learning in institutions. Cetis publications. Retrieved February, 8, 2014.

Dimensions of Openness: Beyond the Course as an Open Format in Online Education by Christian Dalsgaard, Klaus Thestrup is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.