The use of a participant survey, administered at the outset of an online course, can provide information useful in the management of the learning environment and in its subsequent redesign. Such information can clarify participants’ prior experience, expectations, and demographics. But the very act of enquiring about the learner also signals the instructor’s social presence, relational interest, and desire to enter into an authentic dialogue. This study examines the use of participant surveys in online management courses. The first section discusses the informational bridges that this instrument provides. The second section considers survey responses to open-ended questions dealing with student sentiments. This analysis suggests that the survey plays a valuable part in accentuating social presence and in initiating relational bridges with participants.

Keywords: Instructional design; instructional management; social presence; learner engagement; relational dialogue

Benjamin Kehrwald (2008) reminds us that “although technology gets much of the attention in online learning, it is people who make online learning environments productive” (p. 99). While technology provides opportunities and sets structural constraints, the effective design and management of online instructional systems requires an understanding of, and engagement with, those who participate in them. Yet, it is all too easy for the designer/instructor to forget that the distant learner is unique and that a new cohort of students can differ significantly from the previous one. Rogers, Graham, and Mayes (2007) make the point that instructors and instructional designers often assume that “the learner is a lot more like himself or herself than they in reality are… [and] seriously underestimate how important the differences in context are” (p. 212). These natural but erroneous assumptions may have serious consequences on the effectiveness of the learning environments that are created.

In order to make online environments productive, instructors need to be more aware of the uniqueness of participants and to engage with them as authentic, legitimate learners. Rogers, Graham, and Mayes (2007), considering cross-cultural online contexts, also develop a metaphor of bridge-building to highlight acknowledging learner difference, reaching out to that uniqueness, and facilitating exchange opportunities between instructors and their students. The bridge-building metaphor is a central image in the present study. The key question is: How can informational and relational bridges between an instructor and online participants be constructed?

This study examines the use of a participant survey, administered at the beginning of an online course. The Course Participant Survey (CPS) serves two distinct purposes. First, it collects data that might subsequently be useful in managing and redesigning the online learning environment. This might be considered the passive role of the CPS. Second, the CPS demonstrates social (instructor) presence and relational interest and provides an early structure for student response and communication. This is the active, relational role of the survey. The CPS is easily constructed and administered; yet despite—or perhaps because of—its simplicity, it can play a significant role in establishing informational and relational bridges between instructor and student.

The first section of this paper examines the informational aspect of the CPS, looking at the kinds of information that can be collected and the uses to which they might be put. This aspect of participant surveys is useful, fairly obvious, and essentially passive in nature. The second section, however, explores a less obvious and more interactive function of the CPS. It is suggested that asking students directly about themselves, their experiences, and their thoughts at the outset of an online course signals instructor interest, concern, and social presence. An analysis of student responses, taken from a number of online courses, indicates that the CPS confirms social presence and is used by students to acknowledge and respond to feelings of social co-presence, psychological involvement, and relational behavior.

At the beginning of each online course, the author asks each student to complete The Course Participant Survey (CPS). The survey consists of two types of questions. Those at the beginning require simple statements of fact: amount of prior online experience, computer and technological competence, work and supervisory experience, organizational experience and exposure, and the time budget allotted for coursework. These questions seek broad demographic information. They acknowledge attributes of the course participants but in a neutral, statistical manner. In the second section of the CPS, open-ended questions invite participants to make personal statements and disclosures. These might include reasons for course enrollment, anticipated benefits of the course, long-term career and educational goals, and personal feelings and concerns on starting the course. The final question in this section invites participants to share any additional information they consider relevant. An example of the CPS is shown in Appendix A.

The Course Participant Survey is designed to obtain statistical, demographic, and educational information that the instructor considers relevant to the educational experience. Careful thought and ethical concern should be given to all stages of the survey process, including the nature of the questions posed, data storage, confidentiality, and use. The demographic information collected at the beginning of the course significantly increases the instructor’s awareness of students as individual and authentic participants in the learning experience and provides the opportunity to consider relevant characteristics of the cohort involved. Information obtained can serve multiple purposes in organizing and delivering the course, including in-process adjustment, course redesign, and informing strategies for cross-cultural sensitivity, diversity, and inclusion. These will now be briefly considered.

In-process adjustments are those made during the course. They represent departures from plan brought about by significant, unanticipated, intervening contingencies. A review of the information collected in the CPS may alert the instructor to learner opportunities and challenges that were not initially recognized. For instance, if the CPS indicates that the participants in an online management course possess higher levels of management experience than previous cohorts did, learning activities in the present course can be adjusted and retuned to capitalize on this new potential. Similarly, if the CPS indicates that the cohort is weak in distant learning skills or has little prior exposure to online study, in-process adjustments can be made to the instructor’s role and to the management of the educational experience in areas such as assistance, support, and encouragement.

In-process adjustment ensures that variances between anticipated (planned) and actual (possible) performance are reduced. Such adjustments constitute natural responses to feedback in dynamic and evolving learning environments; however, they rely on the instructor’s awareness and experience. As mentioned previously, instructors may be unaware of the unique characteristics of a particular student cohort or of the nature of the challenges and opportunities that those students bring to their learning. Changes in learning activities and assignments need to be considered and implemented at an early stage in the course. Information retrieved from the CPS can alert the instructor to possible revisions and changes even as the course begins.

For participants, the perceived effectiveness of an online learning environment correlates with their degree of engagement in it (Cho & Jonassen, 2009; Hill, Wiley, Nelson, & Han, 2004). One way of initiating higher levels of engagement is by fine-tuning learning activities and revising educational goals to better align them with students’ prior experience, potential, and expectations. In-process adjustment creates an altered online learning environment, which participants can recognize as appropriate and challenging. This provides a basis for fuller and more effective participant engagement.

Sometimes fine-tuning a course is insufficient: fundamental redesign is called for. Here, the analysis of course evaluations can be helpful in re-establishing appropriate educational goals, learning activities, course management, and anticipated outcomes. Reliance on end-of-course (summative) evaluations underscores the cyclical nature of designing and improving learning environments, in which actual learner experiences and accomplishments are elicited, interpreted, and acted upon to improve subsequent offerings of the course (Wiliam & Black, 1996).

The interpretation of summative evaluations, however, must be tempered by an informed appreciation of the nature and characteristics of those who have participated in the course. Gaps between anticipated and actual educational outcomes might indeed suggest a misalignment in the structure, content, and dynamics of the course. However, the variance might also be attributed in part to a significant shift in the course population. For example, poor performance results in the leadership module of a management course might indicate design problems with that module. An analysis of participants’ prior experience, obtained from the CPS, might indicate that this particular student cohort had limited leadership experience compared with previous students who completed the course. The cohort under review has less personal experience on which to reflect and thus less experience to incorporate into their learning. This cohort might be an exception: future course participants might have more leadership experience, similar to those in the past. In a different scenario, CPS data might show a trend in decreasing leadership exposure, which might suggest redesigning the course to recognize this trend.

When engaging in cross-cultural situations, we often lack an understanding of what constitutes cultural difference and how to communicate effectively across boundaries of difference. The CPS is a useful vehicle for obtaining information about learners in cross-cultural, or culturally diverse, distant learning contexts. Distant learning has dissolved geographical and social boundaries but it has not eliminated cultural differences. Cultural assumptions can manifest in many aspects of the online environment: willingness or reluctance to contribute to conferences, communication styles, difficulty in understanding language, and the degree to which individuals are willing to work collaboratively (McLoughlin & Oliver, 2000; Wang, 2007).

Liu, Liu, Lee, and Magjuka (2010) suggest that a “culturally inclusive learning environment needs to consider diversity in course design in order to ensure full participation of the international students” (p. 187). Cultural difference, in terms of values and core attitudes, can be subtle and unanticipated. A fuller appreciation of cultural difference, and a commitment to cultural inclusiveness and diversity, permits more effective learning activities grounded in participants’ cultural assumptions.

Course Participant Survey self-disclosure can sensitize the instructor to cultural issues. This has certainly been the author’s (a Scot) experience in working with international students from Central and Eastern Europe. Self-disclosure provided via the CPS has also been useful in working with military learners who are currently serving with the U.S. armed forces. Understanding the culture in which participants are embedded, and the specific concerns and difficulties that they face, is vital in designing and administering an effective online learning experience (Starr-Glass, 2011). The CPS, even at a symbolic level, indicates the instructor’s willingness to listen to students as distinct individuals, to explore cultural assumptions, to construct bridges to span cultural gaps, and to create a diverse and inclusive learning space. It also allows students to share information that they might not otherwise have shared.

Participant surveys provide a simple but useful bridge for the flow of information that might have an impact on the learning environment. In the second section of this paper, another aspect of the CPS is considered: the bridges between learners and instructors that allow the development and expression of social presence and associated behavior.

Short, Williams, and Christie (1976) originally defined social presence as “the degree of salience of the other person in a mediated interaction and the consequent salience of the interpersonal interaction” (p. 65). Subsequent definitions, sometimes applied to the nature and richness of the communication medium itself and sometimes attributed to those using it, have usually embodied these original aspects. Gunawardena and Zittle (1997), for example, produced a working definition that has proved succinct, enduring, and useful: social presence is “the degree to which a person is perceived as a ‘real person’ in mediated communication” (p. 9).

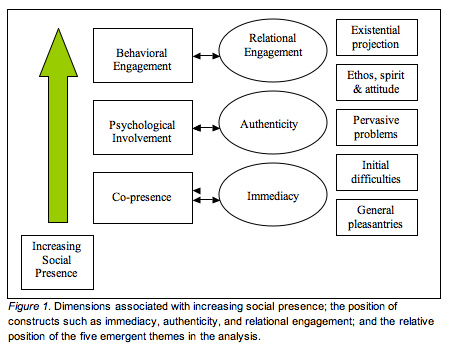

Drawing on an extensive review of the literature, Frank Biocca and others (Biocca, Harms, & Burgoon, 2003; Harms & Biocca, 2004) considered the complexity and confusion that has persisted around the existence, measurement, and effect of social presence in mediated communication. They suggest three distinct, but related, dimensions within social presence.

Psychological involvement is initiated when there is an appreciation of the presence of other psychological and social actors possessing cognitive and affective dispositions. When personal knowledge is not exchanged in distant learning environments, social presence and psychological involvement are inevitably compromised. This can lead to reduced learning opportunities and diminished satisfaction in online learning environments for both students and those who instruct them (Richardson & Swan, 2003; Swan & Shih, 2005). As Robert Starratt (2004) puts it,

…we cannot be present to the other if the other is not present to us; the other’s presence must somehow say this is who I am …. [B]eing present disposes one to act in response to the other, due to the knowledge communicated by mutual presence of one to the other. (p. 87–88)

A significant issue in “being present” online is the presentation of self by the instructor. The instructor, by assuming different roles and personas, can encourage and support exchange among students by confirming, validating, challenging, probing, or conceding a personal lack of knowledge. These efforts can either accentuate “instructor presence” or be directed towards encouraging all online participants to recognize and project their own social presence (Starr-Glass, 2009). Dennen (2007) has indicated that “the skilled facilitator can influence positioning of both self and others, and thus may use positioning in the performative sense as an instructional intervention” (p. 105). Fluid and dynamic social positioning by the instructor develops a more robust social presence that can stimulate not only the psychological involvement but also the authentic engagement of others and increase the degree to which they consider their virtual learning space to be populated by other cognitive, social, and salient learners.

The quality of “being present” is also reflected in the construct of immediacy (Mehrabian, 1967; Wiener & Mehrabian, 1968). Instructor immediacy is understood to include demonstrating a sense of a unique person, expressing emotion, and relating responses appropriately to the needs of participants. Immediacy contributes to, and is in turn encouraged by, higher levels of social presence and psychological involvement (Schutt, Allen, & Laumakis, 2009). In online instructional practice, it has been demonstrated that perceived instructor immediacy can be significantly increased by actions such as providing timely and active student feedback; indeed, both faculty and students seem to agree that this manifestation of immediacy is highly significant in effective online instructors (Bailie, 2011).

Yet another construct associated with psychological involvement and behavioral engagement is authenticity. Authenticity is the quality and extent of personal disclosure. Cranton (2001) defines it as “the expression of the genuine self,” while Brookfield (1997) sees it as a demonstrated consistency and congruence between espoused values and subsequent action. Authenticity not only signals cognitive and affective presence, it also invites interaction. It may well contribute to, and be reinforced by, relational engagement. Dalhberg, Dalhberg, and Nyström (2008) understand relational engagement as a process that is an “open discovering way of being … [the] capacity to be surprised and sensitive to the unpredicted and unexpected … vulnerable engagement … disinterested attentiveness” (p. 98). They also understand relational engagement to include an openness that is “the mark of true willingness to listen, see, and understand … [I]t involves respect … sensitivity, and flexibility” (p. 98).

Social presence, and the constructs associated with it, has a significant impact in distant learning environments. Social presence has been shown to correlate positively with overall participant satisfaction (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1996; 1997). It has also been found to increase participant activity and online interaction (Tu, 2000; Tu, 2002; Tu & McIsaac, 2002). In online discussions, higher levels of social presence are associated with a deeper and richer quality of exchanges (Swan, 2001; Swan & Shih, 2005). Quality of interaction seems to be increased because participants come to an appreciation that they are dealing with “real persons” within the mediated communication environment (Aragon, 2003; Kehrwald, 2010; Maor, 2003). There is also evidence to suggest that social presence contributes to social bonding and a nascent sense of community online (Shin, 2002; Wise, Chang, Duffy, & Del Valle, 2004).

The Course Participant Survey (CPS) is routinely sent to every student at the beginning of the author’s online courses. The courses deal with management theory and organizational design, and, as such, predominantly attract business administration majors. The majority of students are currently serving in the U.S. military, living in Europe or deployed in Iraq or Afghanistan. A previous survey of this population indicates that enrolled students have considerable prior online distant learning experience (mean 4.7 courses; mode 2.0) and long service records (mean 12.2 years; mode 10.0).

This study focuses on a single open-ended question inserted at the end of the CPS: “Is there anything else that you would like to share with me?” It was hypothesized that the question would convey the instructor’s desire and invitation to enter into a dialogue—however partial or limited—regarding learner authenticity and legitimacy: recognition of the learner as a “real person.”

Course Participant Survey information was requested from students in five sections (winter 2010 and spring 2011) of an online course in management theory and organizational design. The sample was opportunistic and included only students registered in the indicated sections. The generalizability of results to a wider cross-college population is therefore limited. The total enrollment for these five sections was 95, and 75 of these students returned a completed CPS. The high completion rate (79%) suggests strong interest. Students were informed that completion of the CPS was voluntary and would have no impact on their participation score for the course. CPS information was regarded as confidential (not shared with other students or faculty) and was stored securely.

Qualitative analysis of text responses was made without assumptions or imposed patterns. A phenomenological perspective was adopted, in which individual responses were understood to be the products “of how people interpret their world, … grasp the meanings of a person’s behavior, … [and] see things from that person’s point of view” (Bogdan & Taylor, 1975, p. 14). The analysis tried to “describe, decode, translate, and otherwise come to terms with the meaning, not the frequency, of certain more or less naturally occurring phenomena in the social world” (Van Maanen, 1983, p. 9). It was considered that such an analytical approach would reveal fragmentary insights and emergent themes within the surveys analyzed (Adams & Schvaneveldt, 1985; Shaffir & Stebbins, 1991).

The degree to which social presence, immediacy, and authenticity was evidenced was determined subjectively using theoretical frameworks informed by the literature reviewed above. Lower levels of social presence (co-presence) were characterized as general statements, which conveyed little about the writer. Increasing degrees of social presence (psychological involvement and behavioral engagement) were characterized by higher levels of immediacy, authenticity, and the suggestion of proto-relational engagement. Generally, these responses were longer and more elaborate, communicated specific personal concerns or dispositions, served as presentations of self, and often suggested a desire for the instructor’s response or recognition.

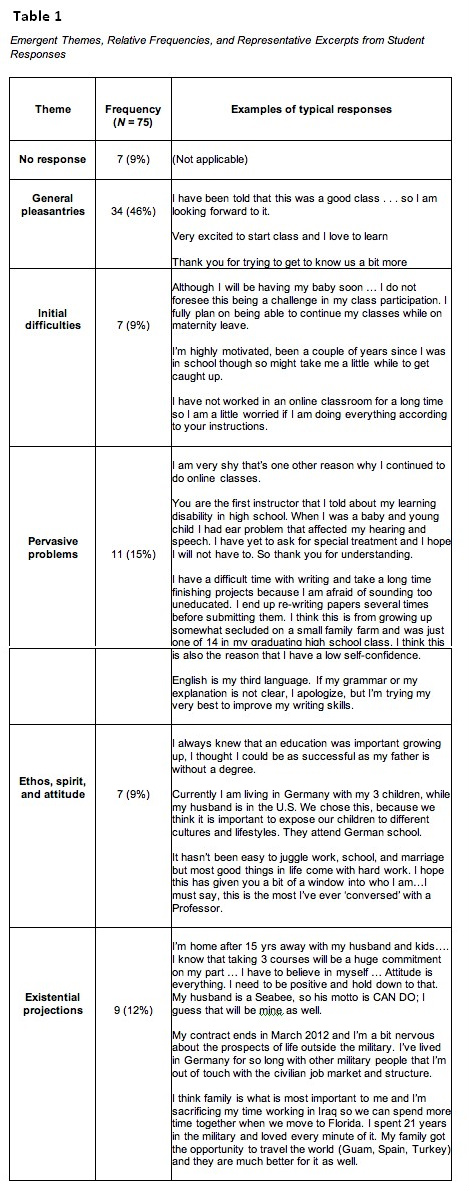

Five emergent themes were identified among student responses. These were labeled general pleasantries; initial difficulties; pervasive problems; ethos, spirit, and attitude; and existential projections. Figure 1 indicates the suggested manner in which these themes relate to increasing levels of social presence and constructs such as immediacy, authenticity, and relational engagement.

Some students simply noted that they had “nothing to add at this moment.” Others added generalized pleasantries, which were typically optimistic, enthusiastic, and forward-looking. These responses were formulaic in nature, indicating a sense of recognition and respect, but lacked significant personal disclosure. These were considered to represent recognition of social presence in terms of co-presence but did not exhibit psychological involvement and relational engagement.

These responses provided additional personal information focused on perceived short-term difficulties. Whether the nature of the identified difficulty was imminent childbirth, extended temporary or redeployment duty with the military, a sense of having been away from school for too long, or unfamiliarity with online coursework, respondents expected that these would be overcome as the course progressed.

These responses reflected commitment to the course and served a pragmatic purpose of alerting the instructor to impending difficulties. In these responses, social presence was evidenced as co-presence; the explanation of immediate and pragmatic concerns was taken as a developing psychological involvement with the new course and with its participants. Relational engagement was not judged to be present in these responses.

These responses presented more extended student concerns that might be significant throughout the course. Items identified ranged from acute shyness, learning disabilities, low self-confidence and educational esteem, and migraine attacks to the use of English as a second language. Several considerations are important.

First, none of these disclosures subsequently appeared in online interactions and would not have been otherwise shared with the instructor. Sensitivity to disclosure, lack of a contextual framework, personal awkwardness, and potential embarrassment within the broader learning community undoubtedly account for much of this non-disclosure. Second, these responses expressed a considerable degree of personal trust. Phrases such as “you are the first instructor that I told about my learning disability”; “because I am afraid of sounding too uneducated”; and “I apologize, but I’m trying my very best to improve my writing skills” all attest to this.

These responses focused on what were perceived as pervasive problems, and, as such, recognized a longer-term impact on the learning outcomes and a longer-term relationship with the instructor. The focus was more on communicating a personal position than on negotiating a course-related issue. This was judged as constituting a high level of psychological involvement and a more developed sense of trust and confidence that move in the direction of relational engagement.

While responses in the previous cluster suggested a beginning of trust, this group assumed that trust was already part of the exchange. Here, the important point was the communication of values that helped to define the writer and to consolidate a unique social actor. This cluster of responses demonstrated a willingness to enter into an authentic exchange, revealing trust and empathy. One of the respondents likened it to providing a “bit of a window into who I am.”

In passing, it might be significant to note that the same respondent also wrote, “this is the most I’ve ever ‘conversed’ with a Professor.” This is an interesting comment for a student who has already completed a number of online courses, and perhaps it speaks to the lack of opportunity for conversations—relational and authentic exchanges—in many of her prior online learning environments.

These expressions were similar to those in the last cluster; however, they were characterized by deeper existential concerns in the students’ lives, or presentations of self. Here, students communicated many things: acceptance of heavy work commitments moderated by a sense of belief in personal capacity and need; concerns about separation from the military and entering an unknown civilian labor market; and the importance of family and the commitment to intercultural values.

These students were not simply articulating positions but had accepted the instructor’s question as a legitimate inquiry into their personal lives. These responses evidenced not only trust in the exchange partner but invited further comment. That anticipated, or inferred, discussion was not necessarily seen as being confined to the online learning environment. This group of responses was understood to present the highest level of relational exchange behavior.

All student responses were categorized under one of the five headings. Table 1 shows the relative distribution of the emergent themes obtained from the analysis. It also shows excerpts from individual student responses to illustrate the themes identified. While the selection of these excerpts is subjective, it is considered that they do provide a representative sense of the five themes identified and serve as anchors to define each of those themes.

This study indicates that at the beginning of one particular online learning experience, the majority of students (79%) responded to a voluntary survey, and, of these, almost all (91%) acknowledged some degree of social presence. Approximately half of these responses (55%) could be regarded as formulaic, demonstrating general social courtesy and pleasantry. These indicated a significant sense of online social presence, in which respondents appreciated that they were not alone or isolated and that there was a mutual focus of attention and interest between “real” persons: co-presence.

The other half (45%) of the responses demonstrated increasing levels of social presence evidenced as strengthening co-presence, psychological involvement, and the beginnings of relational behavior (ranging from “initial difficulties” to “existential projections”). Respondents took the opportunity presented by the CPS to initiate communication and exchanges with the instructor that did not simply relate to the operation of the course but which provided openings into their dispositions, attitudes, and worldviews.

It is suggested that the CPS acts in two different but connected ways. First, it serves instrumentally as an instructor initiative for heightening social presence at the outset of an online course. Here, it figures as one of a number of instructor-centered tactics and strategies deliberately employed to stimulate social presence and make it a salient feature of the learning environment. Second, the CPS can be understood from the student’s perspective as a channel for communicating his/her awareness of social presence. By replying, almost all students indicated that they recognized and wished to respond to an “other” acknowledged as present in the computer-mediated environment. Half of those who responded took the opportunity to demonstrate a higher awareness of social presence and a willingness to engage with a considerable degree of personal authenticity. This level of social presence, it is suggested, would have remained unappreciated had it not been for the opportunity that the CPS provided.

This study does not infer a causal relationship between the administration of the CPS and social presence encountered in the learning environment. Indeed, a confounding factor in making such an inference is that the author characteristically begins new online learning experiences with a high display of social (instructor) presence. The level of personal disclosure may be spurred by this context rather than by the administration of the CPS. The CPS is a way of making social presence salient and evident, and its impact cannot be easily isolated from other structural components of the learning environment that are designed to increase and develop a sense of presence.

The Course Participant Survey, administered at the beginning of a new course, provides an opportunity to learn more about the students entering the learning environment and to accentuate relational exchanges. As the course progresses, participants will contribute to online conferences, share information, exchange opinions, and develop a more acute awareness of the presence of their instructor and peers. Certainly, in creating and sustaining the social dynamics of effective learning environments, instructors can rely on the cues and clues of participants’ online texts. Yet often, critical issues for the individual student, as well as for the collective, are not broached or disclosed publicly. They may be revealed and shared in the privacy of the CPS.

Social presence is a shared property of a computer-mediated communication environment and is recognized and appreciated at different levels by each participant. The instructor is uniquely placed to alter structures and dynamics in order to enhance and sustain social presence; however, he/she is not unique in contributing to social presence. The characteristics of participants are also significant (Mykota & Duncan, 2007). All participants, certainly students within online learning environments, appreciate social presence and use various strategies to improve its quality (Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, & Archer, 1999). In situations where instructors strive to create social presence, this study underscores the level and quality of social presence that exists, albeit latent and unexpressed, even at the outset of online courses.

The high levels of social presence revealed by this study in terms of co-presence, psychological involvement, and behavioral engagement indicate that the CPS is a simple but effective way of eliciting connections between instructor and participants. The CPS is understood as part of an array of tactics and strategies designed to create and strengthen social presence in online environments, rather than as a unique and isolated approach. The CPS provides opportunities for social exchanges that are not witnessed in general online discussions. The participant survey can also be understood as a means of sampling, or confirming, the degree to which social presence is part of the beginning online environment.

While the CPS seems to provide a useful way for creating informational and relational bridges, the limitations of this study should also be acknowledged and considered. These limits include the restricted undergraduate student sample used, subjective assessments used in defining and operationalizing social presence and other constructs, and the analysis of the data collected. More research might provide valuable information about ways in which CPS data can impact the design, decision-making, pedagogical strategies, and learning tactics of the course. Research is required to explore the links between the use of the CPS and subsequent social presence, authenticity, and interaction depth of online dialogue and exchange.

In the meantime, online instructors might consider the advantages and merits of beginning course surveys and see whether such instruments can serve a useful role in their own practice. In efforts to create online learning environments that are built around students, and not instructors or designers, it is critical to construct bridges that facilitate the exchange of information and the sharing of presence. In that, the pre-course participant survey seems to have a significant role.

The author would like to thank the journal’s editors, Terry Anderson and Brigette McConkey, for their courtesy and professionalism. He also expresses his appreciation to three anonymous reviewers who provided insightful and constructive feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Adams, G. R., & Schvaneveldt, J. D. (1985). Understanding research methods. New York, NY: Longman.

Aragon, S.R. (2003). Creating social presence in online environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 100, 57–68.

Bailie, J. L. (2011). Effective online instructional competencies as perceived by online university faculty and students: A sequel study. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 82–89. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol7no1/bailie_0311.pdf

Biocca, F., Harms, C., & Burgoon, J. K. (2003). Towards a more robust theory and measure of social presence: Review and suggested criteria. Presence, 12(5), 456–480.

Bogdan, R., & Taylor, S. J. (1975). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A phenomenological approach to the social sciences. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Brookfield, S. (1997). Through the lens of learning: How the visceral learning experience reframes teaching. In D. Boud, R. Cohen, & D. Walker (Eds.), Using experience for learning (pp. 21–32). Buckingham, UK: Society for Research on Higher Education.

Cho, M-H., & Jonassen, D. (2009). Development of the human interaction dimension of the Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire in asynchronous online learning environments. Educational Psychology, 29(1), 117–138.

Cranton, P. (2001). Becoming an authentic teacher in higher education. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Dahlberg, K., Dahlberg, H., & Nyström, M. (2008). Reflective lifeworld research (2nd ed.). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Dennen, V. P. (2007). Presence and positioning as components of online instructor persona. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 40(1), 95–108.

Gunawardena, C. N., & Zittle, R. (1996). An examination of teaching and learning processes in distance education and implications for designing instruction. In M. F. Beaudoin (Ed.), Distance education symposium 3: Instruction 12 (pp. 51–63). University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University College of Education.

Gunawardena, C. N., & Zittle, F. J. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer-mediated conferencing environment. The American Journal of Distance Education, 11(3), 8–26.

Harms, C., & Biocca, F. (2004). Internal consistency and reliability of the networked minds social presence measure. Presence, 2004, 246–251.

Hill, J. R., Wiley, D., Nelson, L. M., & Han, S. (2004). Exploring research on Internet-based learning: From infrastructure to interactions. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 433–460). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kehrwald, B. (2008). Understanding social presence in text-based online learning environments. Distance Education, 29(1), 89–106.

Kehrwald, B. (2010). Being online: Social presence as subjectivity in online learning. London Review of Education, 8(1), 39–50.

Liu, X., Liu, S., Lee, S.-h., & Magjuka, R. J. (2010). Cultural differences in online learning: International student perceptions. Educational Technology & Society, 13(3), 177–188.

Maor, D. (2003). The teacher’s role in developing interaction and reflection in an online learning community. Educational Media International, 40(1/2), 127–137.

McLoughlin, C., & Oliver, R. (2000). Designing learning environments for cultural inclusivity: A case study of indigenous online learning at tertiary level. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 16(1), 58–72.

Mehrabian, A. (1967). Attitudes inferred from non-immediacy of verbal communication. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6, 294–295.

Mykota, D., & Duncan, R. (2007). Learner characteristics as predictors of online social presence. Canadian Journal of Education, 30(1), 157–170.

Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68–88. Retrieved from http://sloanconsortium.org/sites/default/files/v7n1_richardson_0.pdf

Rogers, P. C., Graham, C. R., & Mayes, C. T. (2007). Cultural competence and instructional design: Exploration research into the delivery of online instruction cross-culturally. Education Tech Research Development, 55, 197–217.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (1999). Assessing social presence in screen text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 50–71. Retrieved from http://www.jofde.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/153

Schutt, M., Allen, B. S, & Laumakis, M. A. (2009). The effects of instructor immediacy behavior in online learning environments. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(2), 135–148.

Shaffir,W. B., & Stebbins, R. A. (Eds.). (1991). Experiencing fieldwork: An inside view of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Shin, N. (2002). Beyond interaction: The relational construct of “transactional presence.” Open Learning, 17(2), 121–137.

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of communication. New York: John Wiley.

Starratt, R. J. (2004). Ethical leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Starr-Glass, D. (2009). Instructor authenticity in mediating a sense of online community. University of Maryland University College. Retrieved from http://www.umuc.edu/distance/odell/ctla/starrglasspaper.pdf

Starr-Glass, D. (2011). Military learners: Experience in the design and management of online learning environments. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 147–158. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol7no1/starr-glass_0311.pdf

Swan, K. (2001). Virtual interactivity: Design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Distance Education, 22(2), 306–331.

Swan, K., & Shih, L. F. (2005). On the nature and development of social presence in online course discussions. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(3), 115–136. Retrieved from http://sloanconsortium.org/sites/default/files/v9n3_swan_1.pdf

Tu, C.-H. (2000). Strategies to increase interaction in online social learning environments. In D. Willis et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2000 (pp. 1662–1667). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Tu, C.-H. (2002). The impacts of text-based CMC on online social presence. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 1(2), 1–24.

Tu, C.-H., & McIsaac, M. (2002). The relationship of social presence and interaction in online classes. The American Journal of Distance Education, 16(3), 131-150.

Van Maanen, J. (1983). Reclaiming qualitative methods for organizational research. In J. Van Maanen (Ed.), Qualitative methodology. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Wang, M. (2007). Designing online courses that effectively engage learners from diverse cultural backgrounds. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(2), 294–311.

Wiener, M., & Mehrabian, A. (1968). Language within language: Immediacy, a channel in verbal communication. New York: Appleton Century Crofts.

Wiliam, D., & Black, P. (1996). Meanings and consequences: A basis for distinguishing formative and summative functions of assessment? British Educational Research Journal, 22(5), 537–548.

Wise, A., Chang, J., Duffy, T., & Del Valle, R. (2004). The effects of teacher social presence on student satisfaction, engagement, and learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 31(3), 247–271.

Class Participation Survey

As we start the course, I would like to know something about you, your educational and career goals, and your present level of knowledge and skills. Information you provide will be treated in confidence and not shared with anyone else. Information you choose to give helps me facilitate this course in ways that might help you learn more effectively and fulfill your educational goals and aspirations.

This assignment will not be graded or used to determine participation.