|

Yi (Leaf) Zhang

University of Texas at Arlington, USA

The purpose of this research study was to explore the influence of Confucian-heritage culture on Chinese learners’ online learning and engagement in online discussion in U.S. higher education. More specifically, this research studied Chinese learners’ perceptions of power distance and its impact on their interactions with instructors and peers in an online setting. This study was conducted at a research university in the southwestern U.S. Twelve undergraduate students from the Confucian-heritage culture, including mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, participated in the study. This study provided evidence that the online setting benefited these Chinese learners’ engagement in class discussion, but it may increase the level of anxiety in their participation. Learning, perceived by the Chinese learners, was more instructor-centered. Instructors were viewed by students as authorities, major sources of knowledge, and possessing high power. As a result, when encountering difficulties in learning, the Chinese learners were intimidated to interact with their instructors. Instead, they tended to seek help from peers, particularly those who shared similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Keywords: Online learning; Chinese learners; power distance

Distance education, particularly online learning, has become more popular and accessible in U.S. higher education as it marches into the arena of borderless education. Online education enables students to access a wider range of educational resources, to pace their own learning process, and to collaborate with others from different cultures and linguistic backgrounds (McLoughlin, 1999; Thompson & Ku, 2005). Online learning relies heavily on advanced computer and internet technologies. While online education brings significant benefits to students, it may lead many to struggle with technical aspects of online courses (Bol & Garner, 2011; Moore & Kearsley, 2011). Students taking online courses must be able to effectively use technology, work in virtual teams, pace themselves in completing assignments, and engage with peers and faculty (Richardson & Swan, 2003).

As international student enrollment in the U.S. reached another record high in the 2010-11 academic year (IIE, 2012), online learning that engages a global audience increasingly catches researchers’ attention for further investigation from cross-cultural perspectives. It has been noted that technology can amplify the cultural dimensions of communication (McLoughlin & Oliver, 2000) and that instructional materials designed from a dominant culture could be challenging for learners from other cultures (Wild & Henderson, 1997). It is not surprising that international students in the U.S. experience technical challenges as well as the obstacles of cultural differences.

This study took a “Chinese learner” perspective due to the fast growth and large number of the Chinese student population in U.S. higher education (IIE, 2012). The term Chinese learner was coined by Watkins and Biggs (1996) and defined by Rao and Chan (2009) as

Chinese students in Confucian-heritage culture classrooms who are influenced by Chinese belief systems, and particularly by Confucian values that emphasize academic achievement, diligence in academic pursuits, the belief that all children regardless of innate ability can do well through the exertion of effort, and the significance of education for personal improvement and moral self-cultivation. (p. 4)

Chinese learners can be found in different geographical locations and political systems, such as mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore (Watkins & Biggs, 1996). Compared to U.S. students and students from other cultures, Chinese learners may engage in online learning at different levels and exhibit different communication patterns. This study explored how students’ cultural backgrounds affect their perception of online learning and engagement in online discussion. More specifically, this research studied Chinese learners’ perceptions of power distance and its impact on their interactions with instructors and peers in an online setting.

A body of literature that focuses on Chinese learners suggests that Chinese learners are significantly different from their Western counterparts. However, these studies have a tendency to define the difference as deviation from Western norms and to imply that Chinese learners are less adequate in a Western learning environment. For instance, early studies (e.g., Ballard & Clanchy, 1991; Carson, 1992; Carson & Nelson, 1996; Dunbar, 1998; Flowerdew, 1998; Samuelowicz, 1987) portrayed negative pictures of students from Confucian-heritage culture as passive learners, reliant on simplistic rote memorization, assessment-driven, obedient to authority, with little interest in critical thinking, and fearful of showing different opinions to the instructor.

It is often believed that the Confucian-heritage culture contributed to these “negative” learning characteristics of Chinese learners. Murphy (1987) suggested that the Confucian ethic of filial piety can explain why Hong Kong students tend not to question the knowledge of their teachers. Bond (1992) agreed with Murphy that Confucian values require people to have respect for age and rank, such as parents, teachers, and seniors. Another factor in Confucian-heritage culture that greatly impacts students’ learning is the concept of “face” (Bond, 1996). “Having face” means that one has status in front of others. It is not surprising that Chinese learners are hesitant to question or criticize their teachers and peers, for the fear of “losing face” or causing others’ to lose face (Bond, 1996).

Some researchers argue that Chinese learners and their learning approaches have been misinterpreted by Western scholars and researchers. As an important source of research on Chinese learners, Biggs (1996, 1998) studied Hong Kong students and provided a less stereotypical description of Chinese learners. He believed repetition was a way of understanding, instead of simply rote learning. He also found although instructors were viewed as authorities they were constructivist educators and believed in student-centered education. Biggs indicated that these learning behaviors can be applied to other learning environments, which explains why many Chinese learners are successful in Western education systems and outperform their Western peers. Volet and Renshaw (1996) obtained similar findings from their study that investigated Singaporean Chinese students in Australian universities. They found that these students were highly responsive to the new learning environment and greatly motivated to achieve success in academic studies. Chan (1999) held a positive view towards Chinese learners as well. He found that Chinese learners value active and reflective thinking, open mindedness, and a spirit of inquiry. Jones (2005) found a considerable level of similarity in the understanding of critical thinking between Asian and Australian college students in macroeconomics. He acknowledged the differences between Asian and Western learners in their learning approaches, but claimed that the Confucian heritage culture does not need to be viewed as a deficit in a Western setting.

Distance education has become an indispensable component in today’s higher education. With the development of technology, distance learning enables students to learn at their own pace, to have broader access to information, and to engage in learning with students from different cultures (Appana, 2008; Harasim, 2000; Kim, Liu, & Bonk, 2005). Interactions that occur in online settings differ from face-to-face discussions. Most of the online interactions, including learner-to-instructor, learner-to-learner, and learner-to-content, are asynchronous, which may reduce the extent of communication, delay replies, and require additional time and effort in preparing responses (Anderson, 2004; Curtis & Lawson, 2001). It was found that this feature could bring both advantages and disadvantages for students’ learning.

Gunawardena, Wilson, and Nolla (2003) claimed that the online medium is beneficial for students’ learning because it frees students from the bonds of physical appearances. Particularly for students whose first language is not English, the online environment provides them with more privacy and extra time to respond to class discussion (Yi & Majima, 1993). Beamer and Varner (2008) indicated that international students felt more comfortable to express their own opinions in the online setting when compared to face-to-face classrooms. Yildez and Bichelmeyer (2003) studied non-English speakers in face-to-face and virtual classrooms, including Confucian-heritage culture students from Taiwan. They reported that international students actually participated more in the online discussion because the online environment focused less on simultaneous responses, which require higher competencies in listening, speaking, and making comments on the spot. In fact, online classrooms provided students with more time to read and prepare their posts. Gerbic (2006) claimed that Chinese students preferred online discussion rather than face-to-face classes because they had better control of the pace of discussion and were more confident in expressing their opinions.

Other researchers noted that Chinese and other Asian students encountered more difficulties in learning online in a Western setting when compared to domestic students. Focusing on Chinese graduate students in the U.S., Tu (2001) argued that the influence of Confucian-heritage culture hindered Chinese students from participating in online discussion and minimized their learning experiences. Pan, Tsai, Tsai, Tao, and Cornell (2003) obtained similar findings. They indicated that Asian students (mostly from Confucian-heritage culture) were reluctant to participate in online discussions. Smith, Coldwell, Smith, and Murphy (2005) conducted a comparative study exploring student online learning behavior between Chinese and Australian students at an Australian university. They found that although these two groups of students demonstrated similar attitudes towards self-managed learning, the Chinese cohort was less comfortable with online learning, more reluctant to communicate with others, and contributed fewer online messages to class discussions. Chen, Bennett, and Maton (2008) studied the adaptation experiences of Chinese international students in Australia. Their study found that Chinese learners needed more teacher control and interpersonal relationships. It concluded that the text-based communication medium did not enhance class participation for the Chinese students.

Cultural attributes can affect learners’ perceptions, expectations, and experiences. Hofstede (2001) defined culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another” (p. 9) and identified five dimensions of culture: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, masculinity versus femininity, and long-term versus short-term orientation. These dimensions were created to measure the influence of a person’s national culture on his or her individual values. The term power distance was first coined by Mulder, a Dutch social psychologist who studied interpersonal power dynamics in the 1960s (Hofstede, 2001, p. 79). Power distance deals with human inequality, which refers to how people in a hierarchical society respond to other individuals who hold positions that are superior or inferior to their own (Hofstede, 2001). In high power distance cultures (e.g., Confucian-heritage culture), people are more likely to accept a hierarchical structure and demonstrate greater respect for position, age, and/or authority than do those in low power distance cultures. This study particularly focused on how Chinese learners’ perceptions of power distance impacted their online learning experiences. The dimension of power distance was chosen because, among all of the five dimensions, power distance was reported to have a greater influence on students’ learning (Selinger, 2004).

Hofstede (2001) compared Asian and American cultures and indicated the former has a greater power distance and stronger uncertainty avoidance, while the latter has a smaller power distance and weaker uncertainty avoidance. Thus, in an online learning setting in the U.S., Chinese learners have to overcome not only challenges that online education brings, but also differences in cultural distance (Wilson, 2001). This study investigated Chinese learners’ perceptions of power distance and its impact on their online learning experiences in the U.S., particularly their interactions with the instructor and other students.

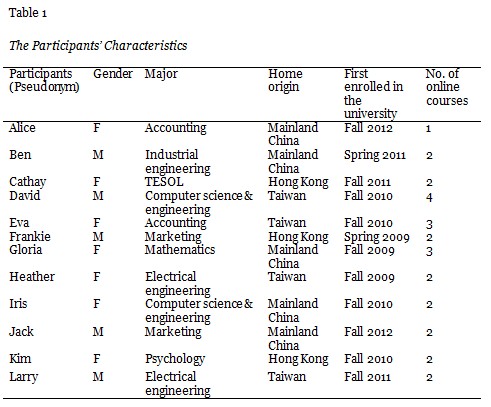

This study was conducted at a research university in the southwestern U.S. Twelve undergraduate students participated in the study. All of the students were from the Confucian-heritage culture, including mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. They were purposefully chosen to ensure that they were qualified to provide necessary perspectives (Creswell, 2009). These participants were from eight different majors, and the length of time they had studied at the university varied from eight months to almost four years. Seven of the participants were female. To protect identification and ensure anonymity, each participant was assigned an English pseudonym.

For the purpose of this study, online courses were defined as “those in which at least 80 percent of the course content is delivered online” (Allen & Seaman, 2006, p. 4). Among all of the participants, Alice had experienced the least online learning as she was taking her first online class when she was interviewed. The other participants had taken a minimum of two and maximum of four online courses in the U.S. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1.

Data were collected from face-to-face individual interviews with the participants. Prior to the data collection, two pilot interviews were conducted to test the interview protocols. At the end of the pilot interviews, the researcher revised the interview questions according to the interviewee’s comments. On average, the interviews lasted 30 to 50 minutes. The interviews were semi-structured, which allows the researcher to explore new information that emerged from conversation with the participants (Creswell, 2009). The interview questions were designed to explore the Chinese learners’ experiences with online education in the U.S. and focused particularly on their interactions with instructors and peers.

Interviews were conducted in both mandarin Chinese and English. The participants were allowed to choose to use either language during the interview. Except for two (Cathay and Kim), all of the interviews were conducted primarily in mandarin Chinese. Most of the students shared their stories in Chinese but responded in English when it came to academic-related terms, such as syllabus, projects, and Blackboard Learn. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim into text in the language that the respondents chose. Member checking was performed to allow the participants to review their responses to the interview questions. In so doing, the participants had opportunities to revise or to add new information (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Chinese transcripts were translated into English for further analysis. The transcripts were first open coded through a first review to identify initial topics and categories. Thematic findings were created by making comparisons and connections between categories (Esterberg, 2002).

The role of the researcher as the primary data collection instrument should not be neglected and his or her personal values should be identified in qualitative studies (Creswell, 2009). As a former international student from mainland China and one who took several online courses in the setting of U.S. higher education, I bring my own understanding of both Confucian-heritage culture and experiences of online learning as an English as a second language learner to this study. My background made it easier to communicate with the participants at the interviews because of our shared experiences and perspectives. However, my previous experiences may shape the way I understand participants’ experiences and the way I interpret the data collected from the interviews. This may lead to certain biases, although every effort was made to ensure objectivity.

This study took a qualitative approach and focused primarily on students at a research university in the southwestern U.S. The findings of the study are not expected to be generalized to other settings. Although this study focused on Chinese learners who share Confucian-heritage culture in common, the researcher acknowledged that this is not a homogeneous group and there is substantial within-group variation, including country of origin, age, gender, socio-economic status, educational experiences, and parental influences.

Through face-to-face interviews with 12 participants, the researcher found evidence that students’ perceptions of power distance impacted their expectation of online learning, participation in class discussion, and interactions with others in the online setting. Four themes emerged from the analysis and are presented with supporting quotes, including engagement in online discussion, lack of instructors’ participation, avoidance of offensiveness and conflicts, and online learning community and support.

Eleven out of 12 participants reported that the asynchronous feature of online learning had been helpful for them to participate in class discussions. This feature gave students time to consider answers, conduct research, and edit their responses. Many participants, particularly those who are experienced in expressing ideas in English, found it easier to respond to discussions in writing than speaking. Ben shared,

I felt more confident participating in online discussion because I can take as much time as I need. In the online discussion, I do not need to worry about if I have any accent, if I fully understand the question, or if I remember all the terms. Writing is not easy, but I have more time to prepare.

Iris appreciated the delayed communication in the online learning environment as well. She shared similar experiences: “In online classes, I can read and reread the others’ posts and when I respond, I am not under pressure that I have to come up with an answer within a minute.”

Nine participants enjoyed online discussion because they were more involved in the process. The Chinese learners felt it was easier to voice their opinions in online discussions. As they indicated, the online setting provides equal opportunities for each student to participate. Frankie compared his experience in both online and face-to-face classes and felt more comfortable in online discussion.

I felt less stress to present my thoughts in an online setting…. I found it very challenging to jump into a discussion in a face-to-face classroom. Some of my classmates can continue talking for a long time and I do not know how to stop them without being rude.

Having studied in a bilingual environment for 12 years in Hong Kong, Cathay came to the U.S. with an excellent TOEFL score and English has become like her native language. Cathay concurred with Frankie although she experienced no linguistic barriers.

I was taught that I should not start talking until others finish talking. However, I found often that I was left out in class discussions in a face-to-face setting…. In online discussions, I have no problems at all expressing my own thoughts and responding to the others. I do not have to fight for opportunities to speak up.

Although most of the participants enjoyed online discussion, eight felt lost when instructors were not involved or not providing guidance in the discussion. Several students reported a high expectation on instructors’ participation in online discussion and demanded immediate feedback from them. Gloria indicated that she had limited gains from class discussions in an online course due to the lack of presence of her instructor.

I did not feel I learned much from online discussions. My instructor basically provided a question for discussion at the end of each class and asked us to post our thoughts and respond to the others’ posts. However, she did not tell us who had better responses, which posts made mistakes, or what we should do to make improvement.

Iris expressed similar frustration. She shared with the researcher that she enjoyed reading the posts of her classmates in online discussions, but learning for her was beyond that. It involved more instructor guidance and participation. She valued the knowledge from her instructor more than from the students.

I missed talking with instructors like in the face-to-face classes. If the discussions were in a traditional classroom, you could always hear from the professor and know what he/she thought about the students’ inputs.

Almost all of the participants expressed concerns of contacting instructors when they have questions regarding class assignments and course materials. Different from face-to-face classes, students in an online setting primarily communicate with their instructors via email or postings on the Internet. The participants worried that their expression may cause misunderstanding or their choice of words may accidentally offend their instructors.

Alice, who was taking her first online course ever in the U.S., shared her anxiety.

It always takes me a long time to draft an email to my instructor. I am afraid that I do not sound polite enough in the email…I am less concerned about this [offending my instructor in an email] in face-to-face classes, because I feel the instructors have a better understanding about who I am. But in the online class, I am only judged by how I wrote. I don’t want to offend my instructor by any chance.

Similar concerns were reported by many respondents when they were participating in online class discussions. These Chinese learners felt either reluctant to express their own opinions or intimidated to make mistakes in their posts online. Several students referred to their online postings as “permanent records.” As Kim indicated, “I don’t want to make any mistakes or say anything stupid… my comments will be posted in the discussion forum for the entire semester.”

When a conflict or controversial topics were presented in the online discussion, many of the Chinese learners chose to “stick with the acceptable answers” and tended to stay away from the heated debate. Ben indicated when there was a controversial discussion he usually chose to post natural comments. He felt “it was pointless to get things more complicated and make others upset.” Cathay indicated disagreeing might be offensive to the others.

It could be offensive if you disagree with someone on their own experiences, cultures, or traditions. Rather than saying “you are wrong,” there are many better ways to present a different idea…. It is especially important to online discussions because our body languages are not seen.

The participants viewed instructors as important sources of knowledge and valued their teaching and sharing. However, they felt more comfortable to turn to peers when they were facing difficulties. The participants indicated that communicating with peers was less intimidating compared to the instructors. Heather found her classmates were responsive when she posted her questions in a discussion forum.

I had some questions regarding an assignment and I decided to try posting them in the [online] discussion forum...to see if anyone will help me…. I actually received responses from several classmates and the fastest one responded to me in less than five minutes.

The participants valued sharing between themselves and their classmates. For some, this was a process of self-validation. Kim found it helpful when she talked with her classmates who had the same question.

I was anxious at first because I thought I was the only one in my class had such a stupid question…. After I shared my concerns with another student I realized that there were a couple of other students in my class wondered about the same thing. We then got together and found a solution…. Knowing you are not alone is encouraging.

When searching for help, the participants particularly favored peers from similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds. They also tended to form groups with those they felt more connected with. Eva was very excited when she found out two of her classmates in an online course were from her hometown in Taiwan.

We three always got together to discuss our homework. If we have any questions, we checked with each other first before we contacted our professor. It helped that we all spoke the same language, but sharing the same culture helped more.

Interviews with 12 international students from the Confucian-heritage culture revealed how Chinese learners interact with instructors and peers and how they perceive their learning experiences in an online setting. The findings of this study also uncovered the impact of power distance on Chinese learners’ online academic experiences in the U.S.

Confirming existing findings of power distance, the Chinese learners demonstrated a strong power distance in the online setting. The participants viewed instructors as a significant source of knowledge and showed greater respect to them. Similar to the findings of McMahon’s (2011) study on Chinese students in U.K. higher education, this study found that the Chinese learners perceived professors as authority figures who are supposed to play a dominant role in class discussion. The students expected to receive guidance from the instructors in online discussion. Thus, reading other classmates’ posts and discussing topics with peers were viewed as less significant than instructor-led learning activities. Indeed, many participants expressed concerns when instructors’ involvement in online discussion was lacking, thus devaluing their entire online learning experience. This echoed Peters’ (1998) finding that Asian students were usually other-ruled rather than autonomous learners.

The findings of this study also indicated that students from the Confucian-heritage culture might be unaccustomed to the online model of learning in the U.S. The Chinese learners can be led towards greater autonomous learning if instructors provide them with explicit explanations and expectations for the class (Kennedy, 2002). The instructors can also utilize multiple media to engage Chinese learners in class discussion.

As discussed above, these Chinese learners believed that instructors played an authoritarian role in learning. Accordingly, the participants demonstrated a strong tendency to avoid approaching instructors when they had questions about course materials or assignment requirements. When they had to write to their instructors, the students spent a considerable amount of time on editing and grammar checking. The students were especially concerned whether their writing displayed a polite manner. For instance, Gloria spent hours drafting an email to the instructor to ensure that it read politely enough. As Liu (2001) argued, the way Chinese learners interact with their instructors is usually impacted by “the socio-cultural factors combined with linguistic and affective factors” (p. 176).

These findings suggest that the Chinese learners viewed their classes as hierarchical structures and considered instructors as superiors in the structure. Instructors in U.S. higher education may need to take additional efforts to approach the Chinese students in order to decrease the distance between themselves and the students. In so doing, the Chinese learners could be better engaged in online discussion and other learning activities.

Communication with instructors was viewed as a formal activity, while interaction with peers was reported as casual and self-ensuring. The participants felt more comfortable to seek help from their peers. None of the participants shared concerns of contacting classmates for assistance in online courses. To minimize the influence of cultural and linguistic differences, many participants chose to form sub-groups with those who were from a similar cultural background and spoke the same language. This may indicate that peers were considered as equivalent counterparts and played an important role in Chinese learners’ online participation. Instructors should encourage more peer-to-peer interactions and create additional learning opportunities among students in online discussion. Instructors should also encourage collaboration among students from diverse cultural backgrounds and promote interactions between international students and their domestic counterparts.

The participants expressed mixed attitudes towards online discussions. On the one hand, the students appreciated the fact that they did not need to provide prompt responses, thus they felt less stressed when sharing their opinions with the class. Many students indicated that they were more engaged in online discussion because each student in class was given equal opportunities to express themselves. These findings confirmed previous research on Chinese learners, international students, and non-English speakers (e.g., Yildez & Bichelmeyre, 2003; Pan, Tsai, Tao, & Cornell, 2003). This indicated that the online environment may provide Chinese learners, particularly those whose first language was not English, with more privacy and additional time to prepare for class discussion by removing barriers of being embarrassed or being shy.

On the other hand, text-based interaction in online discussion requires students to complete a higher amount of reading and writing. As a result, students have to spend more time to review the others’ posts, to respond in English, and to edit their writing with grammar and spelling checks. The participants were very cautious with their responses because they viewed their posts as permanent. They also tended to avoid conflicts and disagreement, which was regarded as impoliteness or offensiveness in the Confucian-heritage culture (Shih & Cifuentes, 2003; Zhang, 2003).

The findings suggest that overall these Chinese learners were more engaged in online discussions, although it may require a higher level of reading and writing. This may indicate that the online discussion provided a more democratic learning environment. This could be attributed to the decrease of power asymmetries in the text-based online discussion. As Chester and Gwynne (1998) indicated, the online environment could make intercultural communication easier because cultural indicators were not as noticeable as they would be in a visual medium.

From a qualitative approach, this study investigated Chinese learners’ interactions with instructors and peers in an online environment. It also revealed the influence of Confucian-heritage culture, particularly power distance, on students’ online discussion experiences. This study provided evidence that the online setting benefited these Chinese learners’ engagement in class discussion, but it may increase the level of anxiety in their participation. Learning, perceived by the Chinese learners, was more instructor-centered. Instructors were viewed by the students as authorities, major sources of knowledge, and possessing high power. As a result, when encountering difficulties in learning, the Chinese learners were intimidated to interact with their instructors. Instead, they tended to seek help from peers, particularly those who shared similar cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

The findings of this study can provide online educators with a better understanding of Chinese learners in the U.S. and increase their awareness of the cultural influence on students’ online learning activities. This study contributed to current understanding of Chinese learners, as well as added evidence to the existing literature. This study may also be relevant for students from other cultures, learners of English as a foreign language, and other students who take online courses. Future studies could focus on other aspects of cultural influence on students’ learning online and interaction of the factors in students’ learning. Gender differences should be examined in future research because power distance might be perceived differently by male and female students.

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2006). Making the grade: Online education in the United States. Needham, MA: Sloan-C.

Anderson, T. (2004). Toward a theory of online learning. In T. Anderson & F. Eilloumi (Eds.), Theory and practice of online learning (pp. 33-54). Canada: Athabasca University. Retrieved from http://cde.athabascau.ca/online_book/ch2.html

Appana, S. (2008). A review of benefits and limitations of online learning in the context of the student, the instructor, and the tenured faculty. International Journal on E-Learning, 7(1), 5-22.

Ballard, B., & Clancy, J. (1991). Teaching students from overseas: A brief guide for lectures and supervisors. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Beamer, L., & Varner, I. (2008). Intercultural communication in the global workplace (4th ed). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Biggs, J. (1996). Western misperceptions of the Confucian-heritage learning culture. In D. Watkins & J. Biggs (Eds.), The Chinese learner: Cultural, psychological and contextual influences (pp. 45-67). Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Center, the University of Hong Kong.

Biggs, J. (1998). Learning from the Confucian heritage: So size doesn’t matter? International Journal of Educational Research, 29, 723-738.

Bol, L., & Garner, J. (2011). Challenges in supporting self-regulation in distance education environments. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 23(2-3), 104-123.

Bond, M. (1992). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Bond, M. (1996). The handbook of Chinese psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Carson, J. G. (1992). Becoming biliterate: First language influences. Journal of Second Language Writing, 1, 37-60.

Carson, J. G., & Nelson, G. L. (1994). Writing groups: Cross-cultural issues. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, 17-30.

Chan, S. (1999).¬ The Chinese learner – a question of style. Education and Training, 41(6/7), 294-305.

Chen, R. T., Bennett, S., & Maton, K. (2008). The adaptation of Chinese international students to online flexible learning: Two case studies. Distance Education, 29(3), 307-323.

Chester, A., & Gwynne, G. (1998). Online teaching: Encouraging collaboration through anonymity. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 4(2), 1-9.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Curtis, D. D., & Lawson, M. J. (2001). Exploring collaborative online learning. The Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(1), 21-34.

Dunbar, R. J. M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6, 178-190.

Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Goodman, J., Schlossberg, N. K., & Anderson, M. (2006). Counseling adults in transition: Linking practice with theory. New York, NY: Springer.

Flowerdew, L. (1998) A cultural perspective on group work. ELT Journal, 52(4), 323–328.

Gerbic, P. (2006). Chinese learners and online discussions: New opportunities for multicultural classrooms. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 1(3), 221-237.

Gunawardena, C., Wilson, P., & Nolla, A. (2003). Culture and online education. In M. Moore & W. G. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of distance education (pp. 753-775). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

Harasim, L. (2000). Shift happens: Online education as a new paradigm in learning. Internet and Higher Education, 3, 41-61.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Jones, A. (2005). Culture and context: Critical thinking and student learning in introductory macroeconomics. Studies in Higher Education, 30(3), 339-354.

Kennedy, P. (2002). Learning cultures and learning styles: Myth-understandings about adult (Hong Kong) Chinese learners. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 21(5), 430-445.

Kim, K., Liu, S., & Bonk, C. J. (2005). Online MBA students’ perceptions of online learning: Benefits, challenges, and suggestions. Internet and Higher Education, 8, 335-344.

Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Liu, J. (2001). Asian students’ classroom communication patterns in U.S. universities: An emic perspective. Westport, CT: Ablex.

McLoughlin, C. (1999). Culturally responsive technology use: Developing an online community of learners. British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(3), 231-245.

McLoughlin, C., & Oliver, R. (2000). Designing learning environments for cultural inclusivity: A case study of indigenous online learning at tertiary level. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 16(1), 58-72.

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (2011). Distance education: A system view of online learning (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Murphy, D. (1987). Offshore education: A Hong Kong perspective. Australian Universities’ Review, 30(2), 43-44. Retrieved from http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/EJ364973.pdf

Pan, C., Tsai, M., Tsai, P, Tao, Y., & Cornell, R. (2003). Technology’s impact: Symbiotic or asymbiotic impact on differing cultures? Educational Media International, 40(3-4), 319-330.

Rao, N., & Chan, C. K. K.(2009). Moving beyond paradoxes: Understanding Chinese learners and their teachers. (p. 4-32). In C. K. K. Chan & N. Rao (Eds), Revisiting the Chinese learner: Changing contexts, changing education. Hong Kong: The Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong.

Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-88.

Samuelowicz, K. (1987). Learning problems of overseas students. Higher Education Research and Development, 6, 21-134.

Selinger, M. (2004). Cultural and pedagogical implications of a global e-learning programme. Cambridge Journal of Education, 34, 223-239.

Shih, Y. C., & Cifuentes, L. (2003). Taiwanese intercultural phenomena and issues in a United States-Taiwan telecommunications partnership. Educational Technology Research and Development, 51(3), 82-102.

Smith, P., Coldwell, J., Smith, S., & Murphy, K. (2005). Learning through computer mediated communication: A compassion of Australian and Chinese heritage students. Innovations in Education and Training International, 42(2), 123-134.

Tu, C. (2001). How Chinese perceive social presence: An examination of interaction in online learning environment. Educational Media International, 38(1), 45-60.

Volet, S., & Renshaw, P. (1996). Chinese students at an Australian university: Adaptability and continuity. In D. Watkins & J. Biggs (Eds.), Learning theories and approaches to learning research: A cross-cultural perspective (pp. 205-220). Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong.

Watkins, D. A., & Biggs, J. B. (eds.). (1996). The Chinese learner: Cultural, psychological and contextual influences. Hong Kong: The Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong.

Watkins, D. A., & Biggs, J. B. (Eds.). (2001). Teaching the Chinese learner: Psychological perspectives. Hong Kong: The Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong.

Wild, M., & Henderson, L. (1997). Contextualising learning in the World Wide Web: Accounting for the impact of culture. Education and Information Technologies, 87(3), 406-423.

Wilson, M. S. (2001). Cultural considerations in online instruction and learning. Distance Education, 22(1), 52-64.

Yi, H., & Majima, J. (1993). The teacher-learner relationship and classroom interaction in distance learning: A case study of the Japanese language classes at an American high school. Foreign Language Annals, 26(1), 21-30.

Yildez, S., & Bichelmeyer, B. (2003). Exploring electronic forum participation and interaction by EFL speakers in two web-based graduate-level courses. Distance Education, 24(2), 175-193.

Zhang, W. Y. (2003). A survey of online teaching in Asia’s open universities. Distance Education in China, 9, 35-42.