|

K. P. Joo

The Pennsylvania State University, USA

Drawing upon cultural-historical activity theory, this research analyzed the structural contradictions existing in a variety of educational activities among a group of alienated adult students in Korea National Open University (KNOU). Despite KNOU’s quantitative development in student enrollment, the contradictions shed light on how the institution’s top-down, bureaucratic pedagogical system collided with individual expectations and needs. In particular, the participants’ critical viewpoints demonstrate the incompatible social roles that the open and distance higher education institution plays in Korean society. For example, while KNOU contributes to extending higher education opportunities for those who have unmet educational needs, the value of the KNOU degree has not been socially acknowledged since there is little, if any, competition in the entrance process. This study also documents how these contradictions were culturally and historically embedded in the participants’ distance higher education activities. Given the persistent contradictions, the research findings illuminate that KNOU’s efficiency-oriented model has not effectively facilitated the students’ learning as its distance higher education system is inevitably based on a compromise between a competitive, quality curriculum and the efficient extension of audiences.

Keywords: Cultural-historical activity theory; contradiction; open university; distance higher education

One of the three major goals of the Sixth International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA VI) was “to review political momentum and commitment and to develop the tools for implementation in order to move from rhetoric to action” (UNESCO, 2010, p. 5). Some institutionalized forms of adult education, such as national training programs for adult educators and open universities, were part of the primary discussion agenda of the conference. Among a variety of national adult education institutions, open and distance higher education institutions are characterized as expanding open educational opportunities for citizens to attend accredited educational services provided by means of innovative pedagogical technologies (Beldarrain, 2006; Visser, 2012).

Globally, technological development has resulted in the increased number of mega-universities built upon the principle of open and distance education (Bates, 1997; Dhanarajan, 2001; Jung, 2005). On a list of largest universities by enrollment (Wikipedia, n.d.), open and distance higher education institutions around the world comprise all top 30 ranks except the state systems of higher education in the United States of America. Those institutions of open and distance higher education have a long-standing commitment to extend participation in higher education because their “fundamental values and strategic priorities” have not changed much since the foundation of the prototypical British Open University in 1969 (Cooper, 2010, p. 70). The modern practice of open and distance higher education has not only transformed the traditional notion of higher education but also broadened the scope of formal educational services available to untypical learners. Investigating adult learners’ experiences in an open university allows us to better understand how open and distance higher education has developed, expanded, and transformed in the institutionally centralized realm of the national education system.

Korea National Open University (KNOU), as a mega, open and distance education institution, has enabled many Korean citizens to participate in higher education both flexibly and conveniently (KNOU, 2011; Yoon, 2006). While only about 10,000 students attended KNOU in 1972, over 170,000 enrolled in 2010. Moreover, 508,835 people had graduated from the institution as of 2010 (http://ide.knou.ac.kr). Despite the positive impact of KNOU on the extension of higher education opportunity and participation (Lee, 2001), KNOU education has varying meanings and values for different individual adult students. As KNOU has developed in the specific socio-cultural circumstances of South Korea, the variety of meanings and values of KNOU as a national open and distance higher education institution has impacted not only individual learners’ motivations but also the Korean culture of higher education.

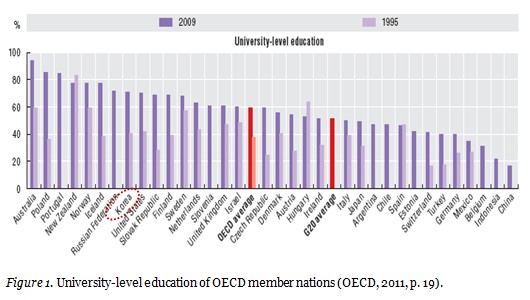

As the rate of higher education has increased in South Korea (OECD, 2011), the social function of KNOU is no longer just an educational institution that gives a second chance to those not having any college degree (McIntosh & Woodley, 1974).

Many college or university graduates participate in KNOU to fulfill their lifelong learning needs (Lee, 2001; Yoon, 2006). According to the Lifelong Education Act of the Ministry of Education, KNOU has started to be regarded as an institution for not only higher education but also lifelong education. Even if this transformed position of KNOU does not have an exclusively negative influence on its social value, the role that KNOU plays in educating those who were alienated from higher education has faded.

In addition, Korea is notorious for being a credential-oriented society, which highly values the final educational degree of a person, as opposed to a meritocracy (Choi, 2009). Scholars have argued that one’s place within the Korean social structure is heavily influenced by academic credentials, or, in other words, so-called credentialism (Choi, 2007; Kim, 2003; Kim, 2004). Such social and cultural views by Koreans regarding higher education exacerbate the social discrimination and prejudice toward people with lower educational degrees (Kim, 2004; Lee, 1997). Given the general law of supply and demand, this also implies that adult learners in distance higher education, whether they have developed high skills and professional knowledge through education, can be socially discriminated against in a credential-oriented society like Korea. In this social context, participation in the inexpensive and open education of KNOU, as opposed to traditional higher education, is less valued in society.

The social bias and other negative aspects of KNOU education can be embodied in KNOU students’ experience of contradictions in open and distance higher education. This study aims to illuminate the origins, patterns, and features of contradictions experienced by alienated KNOU students. The study focuses on identifying structural contradictions in KNOU education as experienced and identified by KNOU students. As opposed to distance education research focusing mostly on the efficiency and usefulness of open and distance higher education systems (Zawacki-Richter, Bäcker, & Vogt, 2009), the phenomenon of contradictions among socially alienated KNOU students highlights critical perspectives of KNOU’s educational mechanism of open and distance higher education and students’ learning experiences in the educational system.

The target student group selected for this research was defined as alienated distance adult learners who could not continue their education due to socio-cultural barriers in school and the society. Marx was “the first theorist to link alienation explicitly to human productive activity” (Sidorkin, 2004, p. 252). Marx (1975) defines alienation as the phenomenon of becoming foreign to the world people live in, claiming that humans create both material and social products and conversely are made by them. Marx argues that productive activity is what links humans to their existence, as they exist only by creating themselves through the social process of production (Brenkert, 1979; Sidorkin, 2004). Alienation as an ecumenical human phenomenon thus manifests itself in the concept of reification in which social relations are conceived as relations between things (Israel, 1976). Schweitzer (1992) says that “alienation is a ubiquitous relational process and social phenomenon which pervades all spheres of human activity” (p. 29).

The concept of alienation drew considerable attention among Western sociologists and socio-psychologists from the middle of the twentieth century (Israel, 1976; Williamson & Cullingford, 1997). The expanded usage of the term is grounded in interdisciplinary facets of the philosophical meaning of alienation. For example, in his famous work On the Meaning of Alienation, Seeman (1959) attempted to articulate five principles of alienation by reconsidering each category within a social learning model, which he characterized as powerlessness, meaninglessness, normlessness, isolation, and self-estrangement (p. 783). Furthermore, Williamson and Cullingford (1997) categorized two of the most influential schools of thought, psychoanalysis and existentialism, which regard alienation as one of the fundamental ideas in mid-twentieth century.

Even though Marx did not explicitly address education, his philosophical underpinnings in regards to alienation have great implications for education (Sidorkin, 2004; Pacheco, 1978). Sidorkin (2004) claims that one of the most conspicuous implications of Marx’s productive activity for education is that students should develop their own essential humanity, which is only feasible by focusing on students’ activity rather than the traditional pedagogical process. Case (2008) also notes that “student alienation arose as a particular focus in response to the student movement of the late 1960s” (p. 324). Along with a renewed interest in the work of Marx and the social problems experienced in the complexity of the contemporary world and post-modernism, the concept of alienation likewise emerged as central in the educational discourse from the mid twentieth century (Geyer, 2001). The problem of social alienation in education is relevant to the welfare of society from a broader sociological point of view.

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) is employed as a means to examine the contradictions of KNOU education and attendant participants’ experiences while engaging in their KNOU educations. CHAT manifests itself in unraveling the heterogeneity of human activity by means of viewing an activity system as a unit of analysis, which allows a critical investigation of class standpoints by “an analysis of the processes of social differentiation within the learning process” (Sawchuk, 2003, p. 43).

Engeström (1987, 2001), one of the most influential contemporary CHAT scholars, has significantly contributed to the contemporary development of activity theory, articulating the methodological usefulness of the theory. Engeström (1987) developed the notion of activity system by combining the system’s theoretical principles with CHAT. Starting from the Vygotskyan concept of subject-object relation mediated by tools or instruments, the activity system model includes communities, rules, and the continuously negotiated distribution of tasks, powers, and responsibilities among the components of the system (Cole & Engeström, 1993). Therefore, the idea of the activity system incorporates these societal and contextual factors influencing and encompassing human activity into the basic model of Vygotsky (Engeström, 2001). Figure 2 describes the structure of a human activity system designed by Engeström (1987).

Through the model of this activity system, CHAT has the ability to perform systemic and systematic investigations of complicated mechanisms of human activities and social and cultural phenomena (Daniels, 2004).

More importantly, activity systems are built upon the basis of constant internal and external contradictions (Daniels, 2004; Engeström, 2001). CHAT considers contradictions existing in/between human activities as the key to understanding human learning and development (Engeström, 2001). It is important to note that contradictions be differentiated from mere problems or disorienting dilemmas from the subject-only perspective (Engeström, 2001). Rather, they exist in human activities because each of their constituents has structural conditions that result from tensions (Lord, 2009).

Engeström (1987, 2001) theorizes four distinct levels of contradictions. The primary contradictions can be grasped in each element of the activity system (i.e., subject, object, mediation, community, rules, and division of labor). Secondary contradictions take place between the constituents of an activity system. And the tertiary contradictions arise when a culturally more advanced activity introduces a more advanced motive-driven object. Finally, the quaternary contradictions arise between the central activity system and the juxtaposed ones that can be related to activity systems of each element of the central activity system. By emphasizing the contradictions in activity systems, CHAT can approach the complexity of reality through a balanced, systemic, and sophisticated analysis (Daniels, 2004; Sawchuk, 2003).

In order to investigate the KNOU students’ previous and current experiences, this study considers several distinct qualitative research approaches and techniques in an integrative manner. It specifically considers ethnography and phenomenology two fundamental methodological approaches. First, given the fact that Korean society and KNOU as social and cultural institutions impose distinct forms of learning, curricula, and pedagogy, an ethnographic approach can provide insights into how the group of KNOU students experienced the preset educational structure of KNOU and realized contradictions. The emphasis of this ethnographic investigation was on finding not just individual, subjective responses to the preset problem, but on the dominant culture that defines the KNOU students’ identity and their abilities to critically recognize the social, structural, and political systems.

Secondly, phenomenology was used to conduct a micro-sociological and cultural-historical analysis of the life-world of participants, which ultimately offers a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of contradictions (Creswell, 1998; van Manen, 1990). Based upon two approaches, structured and semi-structured data collection guides were prepared for interviews and observations. The structured probe comprises preset questions, whereas the unscheduled one was considered in order “to elicit more information about whatever the respondent has already said in response to a question” (Berg, 2001, p. 76).

The research was conducted at KNOU. Its main campus is located in Seoul, the capital city of South Korea, and KNOU also has 13 branch campuses across the country. The research was implemented from early May in 2011 for approximately three months in the meetings with selected groups and individuals. It includes 26 individual interviews, two focus group interviews, and three observations. In both individual and focus group interviews, the participants were asked to describe their experiences of contradiction in KNOU education as well as their pre-institutional experiences of alienation in education and at work. Three observations were intended to capture implicit aspects of contradictions in KNOU in the participants’ interactions and conversations. The research also involved a review of documents indicating the evidence of alienation, discrimination, and inequality in Korean education and society. Furthermore, textual materials that inform problems of KNOU’s distance higher education were the target of document analysis.

A purposeful sampling was designed to find KNOU students representing social and cultural alienation in terms of higher education. Specific groups and individuals were selected from identified KNOU students who had failed to become traditional college students when they were young. Research participants were among those who had no higher education experience other than their current KNOU participation. Thus, transfer students and new students who had experienced any other higher education institutions were excluded. In addition, the research limited participants to students who had at least two years of working experience after high (or lower level) school graduation, as it considered that their social experiences with lower credentials have shaped their identities and ways of thinking of life (Collins, 1979).

Once all the data was put in NVivo 9, the entire interview transcripts, field notes, and other textual materials were quickly scanned for the purpose of grasping overall themes and organizations of the descriptions. Meanwhile, I wrote memos and notes that illustrated my earlier thoughts on specific data units. This procedure enabled me to have a general sense of data characteristics and to contemplate a priori classification originally conceptualized through the preliminary research processes. Once the data set was realigned with the two overarching phenomena (i.e., alienation and contradiction), an intensive analysis of the entire data set followed.

The final analytical phase was to elicit and refine the final themes in the dialectical process of exhaustively reviewing the descriptions pointed to by the emergent codes and categories. In particular, when revisiting the participants’ institutional experiences of KNOU education, the key elements (subject, object, mediation, community, division of labor, and rule) of the activity system in CHAT were considered. Furthermore, other central principles of CHAT such as contradictions, historicity, and multi-voicedness were used for revising the categories and themes.

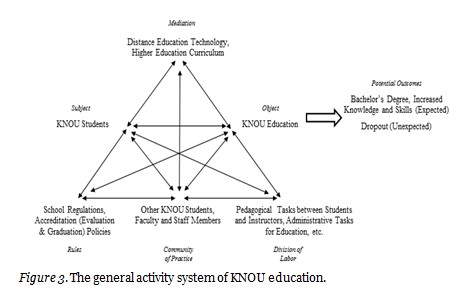

The general activity system of KNOU students is represented by Figure 3.

The community in this activity system is comprised of KNOU students and staff/faculty members. They share distance higher education at KNOU as their common objective. This community is conceptually distinguished from communities of other higher educational institutions and/or other social groups in Korea, as well as different open and distance higher education institutions worldwide. To achieve the motive//object, each member in the community holds different responsibilities. For example, teaching tasks are given to instructors, and most administrative work is assigned to the staff members. Students study, learn, and participate in various formal and informal educational activities.

This triangular activity system represents the interplay of complex elements that constitutes the activity of KNOU education. Although diverse individuals and groups must perform different actions and operations within this central activity system, the KNOU students are the subject group for this central activity system. It is important to note that this model is conceptualized to describe the students’ activity during their KNOU education in general. As the participants had been alienated from the mainstream educational system, their agency as distance learners previously alienated was considered the main perspective from which I revisited this general activity system. Their experiences of social discrimination and inequality due to their low academic credentials led to convergent motivations to attend KNOU and shaped their perspectives on the value of higher education. The participants’ perspectives provide a directional force whereby their specific activity systems and attendant actions are understood.

The motive//object is the KNOU education pursued by the subject group. The object entails a variety of goal-oriented actions such as registering for courses, taking exams, attending face-to-face classes, and organizing study groups. Various motives, which are both material and ideal in nature, lead students to take part in the activity system (Engeström, 1999). The completion of their KNOU education can result not only in gaining the actual college diploma but also in increased knowledge and enhanced educational status. The general object ‘KNOU education’ also involves diverse motives among different groups of KNOU students. In particular, the meanings of KNOU education to the research participants themselves, who attend KNOU mainly to accomplish their previously unmet educational needs, should be differentiated from those of students attending KNOU merely to enjoy learning or to socialize with others. The participants specifically emphasized the motive to increase their employability and self-esteem through KNOU education. For example,

To me, getting a higher educational credential means a lot. I have faced so many moments when I couldn’t develop my career due to my final educational level. I think that, with the KNOU certificate, I will be able to have many more possibilities to try what I wanted to do before. So KNOU may be foundational, like a stepping-stone for my career. (K’s individual interview)

Like her, many participants reflected upon their experiences of discrimination and inequality due to a lack of higher educational credentials. They envisioned the possible extension of their employability with a bachelor’s degree given through graduation from KNOU.

The motive//object of KNOU education involves a variety of cultural and historical particularities that explain the motivations of the alienated KNOU students and the social contexts of the institution. For instance, since KNOU functions as compensation for those who did not accomplish their goals of higher education, the distance higher education provided by KNOU serves as a stepping stone upon which the participants could improve their career prospects in Korea. At the same time, the social position and status of the institution are also embedded in the object – KNOU education. The participants’ critical reflection of the social position of the institution indicates how KNOU education entails negative meanings and values among the participants. In their pessimistic understandings of KNOU education, it remains just an easy and inexpensive alternative to traditional higher education.

I think that KNOU education doesn’t mean that much because I used to work with elite people. I don’t think that I will be taking much advantage of the KNOU degree for my career. KNOU education is not rewarding, as everyone can attend it. It simply means that I may be a little more qualified to apply for jobs requiring the bachelor’s degree. (J’s individual interview)

In a focused-group interview, the participants’ critical perspective on the value of KNOU education appeared more straightforward.

R1: Many KNOU students don’t expose their participation in KNOU to others. They feel shame for attending this school. For example, my friend said I have to go to a master’s program of another higher educational institution… Whenever I heard those kinds of comments, I asked myself, ‘what am I doing here?’

R2: Right, the disregard of KNOU is not an individual problem. It is deeply embedded in our society. To be honest, I don’t want to let my children go to KNOU because our society doesn’t accept the value [of KNOU education]. Even beyond that, our society is oriented toward academic credentials. Particularly, gender, academic credentials, and regionalism should not be underestimated. This is beyond an individual matter.

The participants’ negative perceptions of KNOU’s social position, as shown above, indicate that they themselves were not free from the social prejudice and biases against distance higher education.

The contrasting viewpoints of KNOU education illuminate the incompatibility between the advantages and the disadvantages of open and distance higher education in the capitalist, academic-credential-oriented society of Korea. The participants who were attending KNOU internalized those incompatible social values of KNOU education. In that sense, the participation in KNOU for the KNOU students was both rewarding and stigmatizing. The students’ alienated experiences played a mediating role between the particular socio-cultural circumstances of Korea and their perceptions of KNOU education.

The participants’ experiences of the KNOU education system are categorized into three overarching concepts: assessment, curriculum, and technology. These educational elements are regarded as the key components of the general activity system of a KNOU education. Even if there are a number of mediated instruments which enable the subject (i.e., the alienated KNOU students) to accomplish the object (i.e., KNOU education), I specifically consider the curriculum of KNOU and the technology of distance education as two pivotal mediations for distance higher education of KNOU, because the participants pointed out those two concepts as essential to achieving their educational goals in KNOU.

Like the object, those mediations also involve both material artifacts and symbolic signs and have been socially, culturally, and historically developed in the particular context of KNOU. The KNOU curriculum has been adjusted to cater to national human resource development, which was oriented toward extending educational opportunities via mass education, as well as individual adult students’ needs to consolidate high-level knowledge and skills. These two contrasting objectives were also evident in the participants’ educational experiences of KNOU. Moreover, the highly developed technological infrastructure of Korea has enabled KNOU to establish and implement distance higher education more efficiently and has allowed the students to attend the institution more conveniently.

Meanwhile, assessment and evaluation processes are posited as major rules to accredit students’ learning in KNOU education. As the rule in an activity system regulates how the subject and other community members interact with each other to accomplish the object, KNOU students follow institutional policies – more specifically, the university regulations set for accrediting distance higher education such as evaluation and graduation policies – as the rule of the general activity system in order to accomplish their higher education through KNOU.

To this end, the essence of this activity system analysis is to consider the systemic formation rather than separate connections. By identifying the general model and contextualizing each constituent in the system, we can project the holistic mechanism where the general processes and outcomes of KNOU education were designed and implemented in the complex social, cultural, and institutional settings.

The list of problems of KNOU education recognized by the participants are outlined in Table 1.

Even though these problems were straightforward in the data analysis, structural contradictions of KNOU education that resulted in those problems were not fully comprehensible in each individual’s statements. Thus, in order to identify the structural contradictions as well as the origins of the KNOU students’ negative perceptions, it is necessary to further discuss the multi-level contradictions existing in/between the identified activity systems within the CHAT framework.

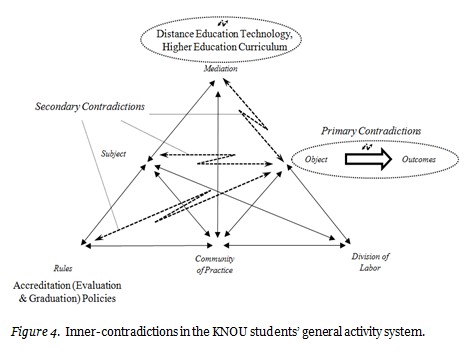

Primary contradictions are rooted in each node of the activity system. Those primary contradictions originate from the tension between the exchange value and the use value in the capitalist socio-economic formations (Engeström, 2001) and arise from the dual construction of the nodes as they have inherent worth (Foot & Groleau, 2011). The research findings specifically indicate that the object and the mediations of the central activity system involve an explicit form of contradictions as experienced by the participants.

Most of all, a primary contradiction embedded in the object arises between the dual principles of KNOU education. KNOU education as open and distance higher education involves the incompatible or conflicting aspects between open/mass and higher education. More specifically, KNOU opens its door to the public by offering inexpensive tuition and positing minimal requirements for entrance. This efficiency-oriented open and mass educational model of KNOU is designed to accommodate as many students as possible. On the other hand, KNOU as a national higher educational institution pursues in-depth and quality higher education in order to produce capable graduates. Those two conflictual principles (i.e., efficiency-oriented open and mass education vs. quality higher education) were embodied in the participants’ critical reflections of the distance higher education system of KNOU.

There are also primary contradictions within the mediations. Distance educational technology is a pure commodity where the relationship between the use and exchange values is evident. For example, KNOU students use technological methods which are intended to facilitate their learning in KNOU. However, they realized that the technology-driven KNOU system failed to accommodate their need to have immediate communication channels and intimate relationships between KNOU community members. H said:

Given the mass education of KNOU, I know it is not easy to respond quickly to every student’s questions... I don’t think we should just study what is given to us, take exams, get grades, and graduate. This is not a certification program. Higher education should be better than this.

In a similar vein, while the curriculum containing subject knowledge in regards to the topics of the course can be viewed as the course contents to enhance students’ learning, the overly theoretical/practical curriculum did not meet the students’ need for learning knowledge and skills relevant to their lives and careers. Y stated:

Now I know the curriculum does not match to my previous motivation to study in KNOU. I thought I would learn and practice the Chinese language, but the majority of the curriculum consists of literature. There are also many areas of cultural studies to be completed, especially during the first and second years. I ask myself, ‘Should I learn this kind of subjects in my old age?’ and ‘How am I going to use this kind of knowledge?’

Unlike other levels of contradiction, the primary contradiction generally remains unresolved (Engeström, 2001; Foot & Groleau, 2011; Sawchuk, 2006) because it is fundamentally embedded within each element of the activity itself (Engeström, 1987). However, the tension along with this primary contradiction makes the activity system constantly transform (Engeström, 2001; Foot & Groleau, 2011) and subsequently becomes the rudimentary ground upon which the other levels of contradiction are conceptualized.

Secondary contradictions occur in the conflicting relationship between two of the nodes in an activity system. By conceptualizing the secondary contradictions, we can grasp the implicit primary contradictions and address a specific problem (Foot & Groleau, 2011). In this research, I identify three types of contradictions existing at the secondary level.

First, the research findings illuminate a contradiction rooted in the relationship between the subject and the object of the general activity system. The participants’ ambivalent perspectives on the KNOU education were intensified from the contradictory relationship between these two elements. While alienation in the educational system and in society motivated students to attend KNOU, their alienation was not sufficiently addressed by the open and mass education of KNOU. The contradictions confronted by the participants who need to complete a higher educational degree as well as to gain useful knowledge and skills for their careers was exacerbated in this particular Korean socio-cultural context where high academic credentials are admired. This conceptualization promotes better understanding of the phenomenon of contradictions not just by observing explicit behaviors of the subject, but by relating the subject’s socio-cultural statuses to the object’s contradictions grounded in the institutionalization of national open and distance higher education.

Second, given the commodity form of distance higher education, another secondary inner-contradiction arises when the rule of KNOU education collided with the object. In the school’s evaluation system, more sophisticated ways of evaluation to assure quality higher education are hampered by the efficient and top-down educational model of open and mass distance higher education. By this structural contradiction, students’ learning was limited to practicing just superficial and memorization-centered knowledge. For example,

I think our KNOU education should lead to our in-depth understanding of subject knowledge. But our examination system is not sufficient to fulfill that commitment. We don’t have to, or cannot, deeply go into the knowledge to get ready for multiple-choice final exams… The KNOU evaluation system asks for simple, pre-set answers. Some may think that the midterm exams are open-ended so that we can express subjective ideas, but a lot of students actually think that even midterm exams ask fixed answers. This kept us from pursuing in-depth knowledge. (B’s individual interview)

Given the essential role of evaluation in guiding students’ learning in education, this secondary contradiction may be resolved by increasing funding for a more diversified evaluation system. The conceptualization of this secondary contradiction makes visible the latent feature of contradiction that was brought about by the bureaucratic system of KNOU education, which was represented in the rule of the central activity system.

Third, another secondary contradiction can be conceptualized in the dialectical relation between the mediations and the object of the central activity system. As the participants were given the institutionally preset pedagogical technology and curriculum, the primary contradictions existing in those two mediations of the central activity system became problematic because they collided with the primary contradiction rooted in the object. If the participants learned merely practical knowledge and skills, then that may undermine the original mission of KNOU as a national institution of higher education. On the other hand, if they had learned overly theoretical knowledge, that mitigates adult learners’ satisfaction and misguides their preparation for advanced careers. This ambivalent aspect of the students’ experiences and perspectives of the KNOU curriculum were also articulated in the individual interviews as below.

It doesn’t seem like college education. When I was taking final exams [multiple-choice exams], I thought that this is almost like high school education. I usually prepared the exams hastily. Sometimes I asked myself ‘Isn’t this too easy to be higher education?’ (M’s individual interview)

It was funny. I didn’t expect at all that we would face this kind of learning contents of KNOU. When I first saw the Korean literature, I was asking myself, ‘Do other freshmen in colleges study this as well?’ (laughing). I muttered myself, ‘Do you [the school] seriously need us to study this old Korean poem?’ So I decided not to study what I thought unnecessary. (C’s individual interview)

Similarly, because the technology-driven KNOU educational system emphasizes mass education, the secondary contradiction between the mediation of distance education technology and the object occurs when the alienated students with high motivation, who expect to receive a quality higher education, faced this mass education approach.

Identifying the secondary contradictions enabled me to elucidate the socio-cultural and structural characteristics of contradictions. Analyzing socio-cultural factors made the contradictions surface, which allowed me to re-conceptualize this phenomenon among the alienated KNOU students in more comprehensive and sophisticated ways.

A tertiary contradiction among the participants arose when the participants looked to resolve the secondary contradictions. For instance, when they realized that the impersonal KNOU approach did not fulfill their expectations, they searched for extra-curricular activities such as organizing study groups in order to supplement their unmet educational needs. Through this activity, they pursued the sense of belonging as a member of higher education and the bond formed through actual, not virtual, interactions with one another. This new way of learning through extra-curricular activities among the alienated students is an outcome of the internal contradictions rooted in the general activity. The participants supplemented the learning materials provided by the school such as online lectures, textbooks, and so on; they also created and participated in their own face-to-face study groups to share information and study together. The ways in which the participants prepared for the exams and assignments were also transformed from individual, self-directed studying to collaborative, interactional activities.

KNOU’s quantitative development in student number is attributed to the administratively optimized and efficiently operating education system of KNOU (KNOU, 2011; Lee, 2001; Yoon, 2006). However, the alienated students’ experiences of contradictions shed light on how KNOU’s top-down, bureaucratic pedagogical system collided with individual expectations and needs. While KNOU contributes to extending higher education opportunities for those who have unmet educational needs, the contradictions identified in this CHAT analysis imply that the open and distance higher education system also entails a variety of problems to those students. This is not just KNOU’s problem; it is rather a common issue that most open, mass, and distance higher educational institutions confront (Garrison, 1989). The efficiency-oriented model of distance higher education inevitably entails a compromise between a competitive, quality curriculum and the efficient extension of audiences (Adams & DeFleur, 2006; Parker, 2008).

To better accommodate those students’ learning needs, KNOU has to reconsider the original mission of Open University – that is, to provide quality higher education to broader audiences. This task requires balancing between extending educational opportunities by opening the institution’s door and assuring the quality of higher education through an effective distance education system (Cooper, 2010; Garrison, 1989). For example, while KNOU screens students by their high school or equivalent records, the British Open University (OU) provides extensive educational opportunities regardless of pre-institutional qualifications. Additionally, the British OU programs involve more individually customized activities within a sophisticatedly designed distance education system as opposed to the efficiency-oriented KNOU education (Open University, 2011).

Given the contradictions in terms of the lack of variety in KNOU’s pedagogical systems, which often collided with students’ needs and lives, it is necessary to diversify the learning contents as well as the ways in which courses are delivered. KNOU also needs to develop more spaces for active communication and interaction as the participants expected a sense of belonging and close interactions with the instructors or between themselves. Lastly, the institution should reconsider any misleading, efficiency-driven evaluation system in order to enhance students’ learning processes and outcomes by customizing it to suit each subject area and course objective.

Adams, J., & DeFleur, M. H. (2006). The acceptability of online degrees earned as a credential for obtaining employment. Communication Education, 55(1), 32-45.

Bates, A. W. (1997, June). Restructuring the university for technological change. Paper presented at The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, London, England.

Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Brenkert, G. G. (1979). Freedom and private property in Marx. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 8(2), 122-147.

Case, J. M. (2008). Alienation and engagement: Development of an alternative theoretical framework for understanding student learning. Higher Education, 55(3), 321-332.

Census data revisited. (n.d.). Retrieved from www.kostat.go.kr

Choi, D. M. (2009). The development process and policy agenda for credentialism in Korea. The Journal of Educational Research, 7(3), 97-118.

Cole, M., & Engeström, Y. (1993). A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition. In G. Salomon (Ed.) Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations (pp. 1-46). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Collins, R. (1979). The credential society. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Cooper, T. (2010). The contribution of the Open University to widening participation in psychology education. Psychology Teaching Review, 16(1), 70-83.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Daniel, J. (1997). The mega-university: The academy for the new Millennium. In International Council for Distance Education (Eds.), In the new learning environment: A global perspective – Conference proceedings (p. 22). University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Daniels, H. (2004). Cultural historical activity theory and professional learning. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 51(2), 185-200.

Dhanarajan, G. (2001). Distance education: Promise, performance and potential. Open Learning, 16(1), 61-68.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki, Norway: Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen & R. L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 19-38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133-156.

Foot, K., & Groleau, C. (2011). Contradictions, transitions, and materiality in organizing processes: An activity theory perspective. First Monday, 16(6). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/3479/2983/

Garrison, D. R. (1989). Understanding distance education: A framework for the future. London, UK: Routledge.

Geyer, F. (2001). Alienation, sociology. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavior sciences Vol. 1 (pp. 388-392). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Israel, J. (1976). Alienation and reification. In R. F. Geyer & D. R. Schweitzer (Eds.), Theories of alienation: Critical perspectives in philosophy and the social science (pp. 41-57). Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff.

Jung, I. S. (2005). Quality assurance survey of mega universities. In Q. McIntosh & J. Varoglu (Eds.), Perspectives on distance education: Lifelong learning & distance higher education (pp. 79-96). Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Commonwealth of Learning / UNESCO Publishing.

Kim, S. B. (2004). Credential society: A philosophical exploration of social identity. Seoul, Korea: Hangil publisher.

Kim, T. J. (2003). The psychological mechanism to reduce educational credentialism in Korean adults: From perspective contraction to perspective expansion. The Korean Journal of Educational Psychology, 17(3), 131-148.

KNOU Institute of Distance Education (n.d.). Retrieved from KNOU website: http://ide.knou.ac.kr

Korea National Open University (2011). The survey of 2011: New and transfer students. Seoul, Korea: KNOU Publishing.

Lee, J. H. (2001). The social role and provision of KNOU as a distance higher education institution. Distance Education Treatises, 15, 77-106.

Lee, K. S. (1997). Credentialism and academic competition. Gosikey, 489, 327-332.

List of largest universities by enrollment (n.d.). Retrieved March 9, 2013, from Wikipedia.org: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_largest_universities_by_enrollment

Lord, R. J. (2009). Managing contradictions from the middle: A cultural historical activity theory investigation of front-line supervisors’ learning lives (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://etda.libraries.psu.edu

Marx, K. (1844/1975). A contribution to the critique of Hegel’s philosophy of right: Introduction. In L. Colletti (Ed.), Karl Marx: Early writings (R. Livingstone & G. Benton, Trans.) (pp. 243-257). London, UK: Penguin.

McIntosh, N. E., & Woodley, A. (1974). The Open University and second chance education: An analysis of the social and educational background of Open University students. Paedagogica Europaea, 9(2), 85-100.

Open University (2011). Assessment handbook. Retrieved from www.open.ac.uk/students

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2011). Education at a glance 2011: Highlights. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag_highlights-2011-en

Pacheco, A. (1978, April). Marx, philosophy, and education. In proceedings of the 34th annual meeting of the Philosophy of Education Society (pp. 209-220). IN: Indianapolis.

Parker, J. (2008). Comparing research and teaching in university promotion criteria. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(3), 237-251.

Sawchuk, P. (2003). Adult learning and technology in working-class life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sawchuk, P. (2006). Activity and power: Everyday life and development of working-class groups. In P. Sawchuk, N. Duarte & M. Elhammoumi (Eds.), Critical perspectives on activity: Explorations across education, work, and everyday life (pp. 238-267). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schweitzer, D. (1992). Marxist theories of alienation and reification: The response to capitalism, state socialism, and the advent of post-modernity. In F. Geyer & W. R. Heinz (Eds.), Alienation, society and the individual: Continuity and change in theory and research (pp. 27-52). New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

Seeman, M. (1959). On the meaning of alienation. American Sociological Review, 24(6), 783-791.

Sidorkin, A. M. (2004). In the event of learning: Alienation and participative thinking in education. Educational Theory, 54(3), 251-262.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2010). CONFINTEA VI final report. Paris, France: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/en/confinteavi

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Visser, L. (2012). Trends and issues in distance education: International perspectives. The Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 7(2), 176-178.

Williamson, I., & Cullingford, C. (1997). The uses and misuses of ‘alienation’ in the social sciences and education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 45(3), 263-275.

Yoon, Y. G. (2006). Troubles and tasks of national mass distance higher education institution: A case study of Korea National Open University. Journal of Lifelong Learning Society, 2(1), 95-120.

Zawacki-Richter, O., Bäcker, E. M., & Vogt, S. (2009). Review of distance education research (2000 to 2008): Analysis of research areas, methods, and authorship patterns. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(6), 21-50.