|

|

|

|

Suresh Chandra Babu, Jenna Ferguson, Nilam Parsai, and Rose Almoguera

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), USA

This paper documents the experience and lessons from implementing an e-learning program aimed at creating research capacity for gender, crisis prevention, and recovery. It presents a case study of bringing together a multidisciplinary group of women professionals through both online and face-to-face interactions to learn the skills needed to be a successful researcher. It reviews the issues related to distance learning programs with particular reference to the e-learning courses and highlights the constraints and challenges in implementing them. Lessons from the experience for future development of similar courses indicate that participant profiling prior to the course, user friendliness of technology, meeting various learning styles, encouraging and rewarding online exchanges, commitment of course moderators, a variety of learning materials, and mixed approaches to learning are some of the factors that can enhance the success of e-learning programs. The paper concludes that enhancing skills of developing country researchers through e-learning programs can increase learning accessibility to those living and working in remote and conflict ridden areas, and bring together a network of professionals to interact and exchange experiences on common problems and solutions.

Keywords: Distance education; e-learning; gender research; Africa

Gender mainstreaming, a process of assessing implications of policies and programs on men and women to ensure gender equity, has been a priority in different areas of development since the 1990s (UN, 1997). However, this concept was quite neglected in crisis prevention and recovery, where communities, regions, and nations attempt to design programs to improve the livelihoods of a population that is recovering from natural and man-made calamities. With the United Nation’s Resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security, and the United Nation’s Eight Point Agenda, the practice of gender mainstreaming in crisis prevention and recovery is increasing. Despite this growing awareness and practice, the ability to respond effectively with programs and policies during crisis is highly limited by the scarcity of gender-specific or related research and analysis in crisis prevention and recovery. This is partly due to lack of capacity to develop research proposals and raise resources for the implementation of the research projects. This paper documents the lessons learned from an effort to narrow this capacity gap through a combination of distance education and face-to face approaches.

Through intensive training and mentorship with developing country researchers and junior faculty, the collaborative effort described in this paper responded to the glaring absence of intellectual leadership on gender dimensions of crisis prevention and recovery, especially from within affected communities in developing countries. Decades of crises in several developing countries in Africa have left many research and academic institutions in dearth of material, human resources, and social capital (Fukuyama, 2004). This has negatively influenced gender-related research with respect to training women researchers, setting research priorities, and accessing research funds and other knowledge resources such as conferences, journals, and publications. Although gender mainstreaming itself cannot remedy these long-standing and cumulative impacts, this collaboration aimed at ensuring those most affected by crises share in the process of building new knowledge and in shaping intellectual and research agendas. Further, it aimed at strengthening research capacity through a combination of distance education using digital approaches combined with the face-to-face building up of practical capacity for research proposal development.

This paper documents the experience and lessons from implementing a combined e-learning and face-to-face program aimed at creating research capacity for gender, crisis prevention, and recovery (G-CPR).

Capacity development strategies increasingly recognize that reaching out to a larger number of participants through innovative delivery of educational programs is vital for speedy strengthening of local capacity. Successful open distance education programs in the last three decades have spawned greater interest in the use of information and communication technologies in the design and delivery of capacity development programs (Gulati, 2008). However, challenges to expansion of courses and curriculum to information and communication technology (ICT) based delivery methods have come from different directions (Okonkwo, 2012). Skeptics continue to question the quality of electronically delivered educational programs. It is not always clear how the participants who get their education through online courses fare compared to those who receive face-to-face course content in formal settings (Ogunsola, 2010). The debate is nowhere more prominent than in the international development community, where there is a need to improve local capacity of professionals in developing countries who live and work in remote and conflict ridden areas. In addition, assessment, analysis, design, and implementation of programs and projects have become critical for increasing the effectiveness and sustainability of intervention programs that attempt to enhance the capacity for crisis prevention and recovery (Leary & Berge, 2006).

Nevertheless, research and educational institutions and capacity development programs have attempted to spread their reach to unreachable populations through various forms of distance education for decades beginning with the first generation method of printed correspondence learning methods. With this same primary goal of expanding their reach to previously unserved populations, during the mid to late 1990s, there was a renewed explosion of distance education using e-learning, or online/web-based learning delivery methods (Mandinach, 2005). The proliferation of web-based learning has been spurred in part by technological advances and economic considerations as institutions look for more cost effective methods of reaching ever greater populations (Potashnik & Capper, 1998; UNESCO, 2002). The quantity of potential learners continues to increase as developing countries improve their technological infrastructure and more people have internet and broadband access.

Further, as technological advances in media opened up new avenues for distance education, the involved institutions sought to move beyond the more basic delivery characteristics of flexibility in time, place, and pace to address issues such as advanced interactivity in learning in what is now termed the fifth generation of distance education (Taylor, 2001). However many institutions are still in the initial stages of incorporating web-based, open, and distance learning into their repertoire of capacity strengthening and higher education programs. Web-based learning creates new variables, constraints, and issues, making it fundamentally different from face-to-face learning environments (Mandinach, 2005; Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012). As they gain experience incorporating web-based learning into their existing programs, institutions will begin to find their niches in the new online learning environment. Yet, documentation of the issues, constraints, and challenges in implementing online courses continue to be limited in developing countries.

The demand for web-based education has been increasing along with the growing emphasis on the role of continuing education for sustaining gains from development assistance. Lifelong learning through continuing one’s education has become a competitive necessity. As a result, the profile of the typical learner who seeks open and distance education is changing. So is the type of learning activity that best suits such needs. Learners are older now that there is a greater demand for professionals to continue learning and expanding their skill set well into adulthood. The motivations that drive adult learners are different from traditional school-age learners, as is what they typically want to get out of a learning opportunity. Adult learners are particularly motivated by interests in professional advancement and want to make use of their own life experiences and be able to directly apply learning experiences to their professional challenges (Howell, Williams, & Lindsay, 2003). Moreover, adult learners are particularly interested in the implications and applications of what they are learning (O’Rourke, 2003). These learners are most interested in short courses and executive mid-career style courses that will fit their needs but not interfere too much with their busy lives. Online, web-based learning is well-suited to these learners with its wide range of potential learning tools and capacity to directly relate to their professional lives (Freeman, 2004).

In the mid to late 1990s, many capacity strengthening and higher education institutions rushed to fill this new demand for continuing education. The first generation of online learning (or the fourth generation of distance education) was based on translating traditional face-to-face, classroom instruction to be posted on the internet (Johnson & Aragon, 2003). These courses are characterized predominantly by plain text materials and resources from traditional classroom materials being posted online. The flow of communication is in one direction, from the instructor to the students. As online course designers expanded their understanding and knowledge of the full capacity of web-based learning management system programs, the flow of communication has shifted to a multi-directional, free flow of information generating from both learners and instructors and flowing between learners and instructors/tutors and amongst learners themselves (UNESCO, 2002). With the proliferation of institutions developing web-based learning programs (e.g., higher education institutions, capacity strengthening institutions, international development institutes, and private sector organizations, etc.) the market for these programs is becoming highly competitive (Smyth & Zenetis, 2007). Specialization in distance education programs is taking place as institutions attempt to meet the demands of specific segments of the learner population (Howell et al., 2003). As more courses, degrees, and universities become available through web-based, distance education programs, there will be an increase in the demand for high quality course offerings and lower tolerance for those of poor quality. Related to the growing competitive environment in web-based learning programs is a growing trend toward developing institutional partnerships in order to design, develop, and deliver online courses (Howell et al., 2003; UNESCO, 2002). Partnerships are emerging between colleges and universities as well as with private organizations, international development institutions, and institutions dedicated to capacity strengthening.

As discussed above, web-based, distance learning programs enable institutions with capacity strengthening programs to reach learners that might not be able to participate in more traditional short courses and other face-to-face learning activities. Although female professionals face similar challenges as male professionals with respect to capacity development, women are particularly disadvantaged due to their limited mobility and additional household responsibilities. Given the challenges of time and space, not to mention the active schedules, heavy workloads, and travel schedules of typically targeted learners, capacity strengthening workshops often are not able to get the people they most want because the targeted learners cannot be physically present for a one- or two-week short course. In addition, the ebb and flow of donor interest in funding capacity strengthening components in projects as well as the lack of sufficient in-house resources often prevents institutions from conducting the full number of capacity strengthening workshops and short courses in the number of countries that is needed to make a significant impact.

International organizations have shown a high level of interest in incorporating web-based, open, and distance learning programs to expand the delivery of workshops, short courses, and training programs. The key reason for the development of distance education programs is expanding the institution’s reach to a larger pool of target learners. Online learning activities enable the institution to broaden its reach to target learners, limited only by the internet connectivity of the targeted geographical location. A global trend is the rapidity with which many developing countries have embraced the potential of open and distance learning and are incorporating information communication technologies (ICT) as a strategy to alleviate problems of access, equity, and quality (UNESCO, 2002). As developing countries improve the national ICT infrastructure, international development organizations are able to access ever more remote rural areas, and with lower unit costs than traditional face-to-face workshops, they are able to offer courses on a greater range of subject matters while reducing capacity strengthening expenses (Freeman, 2004).

Web-based, open, and distance learning programs can also be used to complement other programs initiated by the institutions. For example, in recent years there has been a surge in the number of portal-based projects. The long-term plans for these portals often propose the integration of capacity strengthening components such as short courses on the various subject matters addressed by the portal contents. Furthermore, web-based learning can be used to complement any program; it is not limited to those projects related to or using ICTs.

Another reason for development organizations’ interest in web-based learning is that using online technologies to offer distance education programs presents an opportunity to build and strengthen networks of learners around a central theme. One of the methods to build sustainability into development programs is through the creation of in-country, stakeholder networks. Online courses often incorporate discussion forums to stimulate dialogue on a particular subject matter between learners; this flow of communication and ideas can further strengthen networks and develop a deeper sense of identity as a member of a particular network.

This paper using a case study examines recent experiences in offering web-based learning opportunities. It asks what is known about the past successes of online learning programs and how this knowledge might help in the future applications of web-based learning for international development. In what follows a case study of the recently offered e-learning to build research capacity is described for potential lessons.

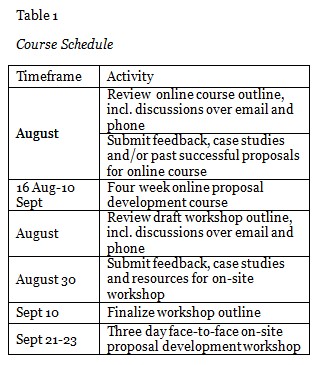

An online proposal development course was developed and piloted to a group of selected partners of the International Development Research Centre’s (IDRC) “Women’s, Rights and Citizenship Program in Africa and the Middle East”. Key components of the course included problem formulation and conceptualization, development of research questions, choosing the appropriate methodology, and drafting a peer-reviewed research proposal. The project involved three sets of strategic activities.

The first set of activities included the preparation of online materials and consultation with a group of well-established researchers for improving the course content and including relevant literature on gender, crisis prevention, and recovery (G-CPR). The second activity involved implementation of an online course on an open source platform. The third set of activities included bringing the participants together through an onsite workshop for face-to-face discussions on their draft proposals—an output of the e-learning course—and adding value to the content of the proposal by offering suggestions and comments on the content. These activities were followed by an evaluation by the participants of the course to receive their feedback for the further improvement of the course content.

The e-learning program described here responded to the institutional and funding challenges faced by younger female and male researchers who want to spend extended periods of time engaged with the conceptual, epistemological, and methodological challenges of gender, crisis prevention, and recovery. By strengthening the skills of young researchers and junior faculty, thereby strengthening their professional profile, and increasing their access to intellectual and financial resources, this course would play a crucial role in ensuring that the field of gender, crisis prevention, and recovery would be informed by those most affected by crises and would have a committed and uniquely qualified cadre of researchers for decades to come.

In a research field largely dominated by northern institutions, southern researchers and practitioners often lack the necessary capability to voice their concerns on gender and crisis. One of the major obstacles to building their research capacity is the availability of funds for nurturing those who have talent and an inclination for a research career. They lack the skills needed for fund raising such as proposal writing and are unfamiliar with the complex rules and conditions of the grants they are applying for. This applies even more for women whose specific perspectives have long been ignored in both southern and northern contexts. Consequently, their valuable knowledge easily gets lost and remains undocumented. Meanwhile interactions with donor agencies remain imbalanced and are characterized by limited ownership of southern partners as well as a lack of response to the actual needs on the ground.

In order to respond to the lack of fund raising skills, the major objective of this collaboration was to build southern capacities in designing research proposals on topics related to gender, crisis prevention, and recovery. Strengthening researchers’ skills in proposal writing is a sustainable way of helping them to access grants that will increase knowledge and understanding and enable profound analyses of G-CPR related themes. With these skills, southern researchers will be able to develop high-quality proposals that not only increase the chances of funding and actual implementation but also the standards of the research itself. Given the theme provided by IDRC, a funding agency, and the growing attention paid to women’s participation in politics, this proposal course was tailored in this specific area by providing examples relating to women’s political participation. The course built on a growing body of practice that has provided important insights about the challenges of addressing gender issues, responding to women’s unique needs, and supporting their contributions in recovery processes. Further, literature related to feminist methodology and women’s political participation formed the foundation for the entire course, the assignments, and the readings.

Although women and communities most affected by the crises have been engaged and consulted in the development of programs and policy responses through rapid needs assessment and ‘lesson-learned’ case studies, it is sobering to note that very few southern researchers have been the lead authors, researchers, or principal investigators. Consequently, their ability to frame the research questions, choose the appropriate methodologies, and correctly interpret the findings remains under-developed. The approach to the development of the course is based on the belief that support for proposal development among southern researchers is a crucial step in helping overcome the obstacles that have limited the contributions of southern intellectuals and researchers in shaping the policy, research, and program responses of the ‘international’ community and their reliance on well-established international non-governmental organizations as ‘executing’ partners.

An online proposal development module was developed to meet the needs of the target audience, to address thematic priorities of IDRC’s program on Women’s Rights and Citizenship in Africa and the Middle East, and to advance the mission of the Global Center of Research on G-CPR. The course was customized to develop a full-blown research proposal in the area of “Young Women’s Political Participation in Conflict-Affected Areas in Africa and the Middle East.” Regional experts in the field of gender and crisis prevention in Asia and Africa were consulted to provide input for the course and to propose case study materials. Using an interactive process, the course was designed to engage participants with one another and course facilitators, to develop the basis for a comparative framework, and to strengthen regional and cross-regional collaboration.

A course moderator moderated the course and was available to the course participants through email, chat in discussion forums and Skype, and phone conversations. Related course readings before and after the course lessons and the course readings formed the integral component of each week’s course lessons. Similarly, a follow-up process for evaluation, providing personalized and individual guidance to participants in finalizing their project proposals, and presentation of the fully developed proposal by the course participants in an on-site workshop formed the specific component of the course design and a mechanism for enhancing and improving the effectiveness of the course. Further, to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the outcomes of the online course and workshop, one to one supervision both from the course moderator and from thematic resource persons formed the strategic element of the course design.

This e-training course aimed to provide hands-on technical assistance in the development of action research proposals. This course also sought to provide the opportunity for researchers in the G-CPR network to use a real-life proposal in their course work and emerge with a high quality proposal that can be submitted for peer review and further consideration.

Specific objectives included:

The course ran for four weeks and its lessons and modules were organized on a weekly basis. This helped to facilitate active dialogue between participants and the course moderator as well as provide an organized structure to the dialogues. However, participants were encouraged to work at their own pace and during the hours most suitable for their schedule. It was suggested that lessons be discussed and any questions be raised regarding specific lessons during the week in question.

An assignment was given to the participants at the completion of each lesson to test the participant’s understanding of the lesson concepts. Participants were asked to turn in their assignment to the course moderator prior to moving on to the next topic. All participants were encouraged to participate in open dialogues that took place in the form of open forums or chats. Due to the time difference between the participants and the course moderator, forum chats or direct email correspondence formed the main basis of communication.

The course was targeted at advanced and starting researchers who seek to translate their experiences into academic research. Applicants at least had a master’s degree and showed interest and/or experience in gender and crisis related issues. It was envisioned however that these areas of interest would be broadly sketched to encourage creative and interdisciplinary approaches to further expand this field of knowledge.

Nineteen participants were selected by IDRC through a careful review process. Three specific criteria were used to select the participants: They must come from an organization that deals with gender mainstreaming in relation to crisis prevention and recovery, they must be women, and they must have a master’s degree and above on a subject related to gender issues. However, special consideration was given to proposed research ideas that integrated gender perspectives, had policy relevance and potential contribution to the field, and had a clearly articulated methodology and feasible objectives. Care was also taken to ensure a diverse group of participants in terms of backgrounds and professional expertise.

An advisory group was established to provide guidance on the development of an online research proposal development course. A multidisciplinary group of advisers, with expertise in feminist methodology, theory, gender analysis, and relevant regional and thematic areas were asked to

Each advisor was assigned a country team to review the IDRC research partner’s draft proposals thoroughly and to facilitate the on-site workshop. The relationship established with the advisors in this collaboration can be further developed and used in future training designed to strengthen the capacity of researchers and practitioners working in conflict affected, developing, and transition countries. The advisors were expected to contribute not more than 18 hours of time via email exchanges and phone conversations.

In order to improve the draft proposals prepared by the participants of the e-learning course, a face-to-face workshop was held in Cairo, Egypt. The workshop brought together the teams of 15 researchers from Egypt, Ethiopia, Malawi, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Tunisia. While the two participants of the Cairo workshop were not able to attend the online proposal development course the remaining 13 participants participated in the online course. It provided an opportunity for the participants to present the draft proposals and to receive feedback from the resource persons. In addition, the workshop also helped the participants through various thematic presentations on the issues, the method, and the communication aspects of research on gender and crisis and recovery. Participants also brought out the constraints and challenges they faced in taking the e-learning course.

The value addition to the proposals from the face-to-face workshop was clear from several angles. First, participants valued the direct feedback from the thematic experts who commented on the proposals after the presentation by the researchers. Second, the additional knowledge that the participants gained from the thematic presentation helped to fill the thematic gaps and strengthen the content of the proposal further. Third, the workshop was an opportunity to exchange ideas and challenges faced by the researchers in the development and implementation of research activities. It was clear that there were several common challenges confronting the researchers in the developing countries. How individual researchers in specific countries overcome these challenges gave a new perspective to others. Fourth, meeting the representatives of the sponsors in person and hearing their expectations helps to increase the chance of funding, if the researchers in revising the proposals address the concerns raised. Finally, the presentations on research and communication methods helped participants to learn research approaches and incorporate them in their revised proposals.

Course evaluation by the participants is a key feedback mechanism for improving the course content, pedagogy, and delivery methods. An evaluation questionnaire was developed and emailed to all the participants of the e-learning course and the participants of the face-to-face workshop. Follow-up phone calls were made asking for evaluations from the participants. There were a total of 21 participants in the online proposal development course and the Cairo workshop. A total of 14 completed evaluations were obtained that included two evaluations from the participants who attended only the Cairo workshop, three evaluations from the participants who attended only the online proposal development course, and the remaining nine from the participants who attended both. The responses from the participants and the notes taken during the phone calls were analysed for common patterns of suggestions and feedback from the participants. Key outcomes and lessons suggested by the participants were documented. The results of the evaluation are discussed below under different headings.

The majority of the participants found that the course contents were useful, clear and comprehensible, presented in a logical sequence, and relevant to their area of proposal development. However, almost 17% of the participants felt that more information should be incorporated in the lessons along with contextual, practical, and relevant examples. Although most of the participants agreed that the course lessons were sufficiently detailed and inclusive for proposal writing, a need for lessons on measuring the impacts, data-analysis techniques, and use of the software (SPSS, STATA) was also brought up and highlighted in the evaluations. Further, a deeper orientation in research design and methods, particularly action based, was also called for.

Almost 83% of the participants agreed upon the clarity, comprehensibility, and relevance of the reading material to the proposal development. On the other hand, the survey responses showed the demand for a relatively simple and low volume of reading materials, although the proportion for such demand constituted not more than 16%. While all the course participants agreed upon the relevance of course assignments, only 67% agreed upon the easiness of the course assignments.

At the completion of the online course, almost 45% of the participants revised their research objectives and methodology. Eighteen percent of them revised their research questions and revisited literature to back up the research questions. Although these are the areas mainly revised by participants after taking the course, the participants found the course lessons helpful to improve their research design, budget, and data collection tools. Adding simple, relevant, and easy reading materials, backing up course lessons with more relevant, contextual, and practical examples and illustrations, and providing more coordinated and longer mentorship from the advisors could help improve the effectiveness of the online proposal course.

Almost 75% of the participants contended that the course should be less intensive and should span more than four weeks. Further, in order to write a proposal concurrently with the course lessons, the course should run for more than eight weeks. Around 67% of the participants agreed that there would be a benefit in peer reviewing each other’s assignments during the open course and many are willing to invest time to do this.

Although many participants found that the Moodle e-learning platform was easy to access and navigate, the problem of insufficient internet access and slow speed was the main hurdle for them throughout the course. Despite this problem of slow internet speed and limited access, 67% of the participants expressed their interest to participate in another online course offered through the Moodle platform.

The course moderator played an important role in the learning process. In addition to being on constant watch for learning support needed by the participants, the moderator also played the role of knowledge manager, sharing the issues, constraints, and challenges faced by one participant with all others and inviting responses for solving issues from the participants. Given the challenges of poor internet connectivity, the role of moderator in keeping the participants on the same page is crucial for the success of the program. The course moderator also needs to be well versed in the content to give regular feedback and answer questions from the participants as they come up during the e-learning program. Moderating online courses with participants from developing countries requires flexibility and empathy to understand the challenges they face. Regular encouragement and motivation is also needed from the moderator.

Around 75% of the participants constantly communicated with their advisor through emails, Skype, and phone regarding the proposal content and the course assignments. The participants who communicated with the advisor found that the advisor’s comments were clear and comprehensible and demonstrated substantive proposal writing experience. Of those who communicated with the advisor, almost 89% revised their proposal to include the advisor’s comments and suggestions. Based on the advisor’s suggestions and comments, the most revised sections in the proposal included research methods, objectives, data collection tools, defining target population, and sample size.

All participants concurred that participating in an online course was a good investment of time. Around 91% of the participants recorded 4 on a scale of 1 to 5 — with 1 being the lowest score and 5 being the highest score — for the effectiveness of the course. The recommendations from the participants for further improvement of the course included:

Around 91% of the participants felt that the location of the workshop was well chosen and well organized. A majority (91%) of them agreed that the objectives of the workshop were relevant, clear, and realized fully. Most of them found that the presentations made during the workshop were clear, comprehensible, and relevant to their work. The most useful and liked presentations, based on the survey response, included “Result dissemination and research methodologies” and “Exploring gender mainstreaming through the lens of a gender and crisis prevention and recovery framework”. Although the workshop was acclaimed in meeting participants’ expectations, around 10% of the participants commented on inadequate opportunities to make comments and contribute to discussions. Similarly, around 37% felt that time allocated to discuss each team’s research project was inadequate.

The workshop was able to contribute to developing an understanding among the participants of possible methods and ways of comparing regions and to generate new thoughts on researching young women’s political comparisons. Further many participants mentioned they would apply the lessons learned from the workshop in various forms and approaches, which could include revising the draft proposal, using the experiences of other countries on similar issues, and drawing cross-country comparable results, among many others. All participants showed a willingness to forge relationships with cohort members through continuous communications. In addition, the workshop provided a platform to establish a cross-country network for four countries: Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan, and Tunisia. This network was established through the initiative of the team of researchers belonging to the respective countries. They plan to meet four times within a span of two years to discuss possible ways of advancing research and to share experiences and resources. The recommendations from the participants for further improvement of the workshop in future included: providing more time for individual project discussion in small groups and maintaining and fostering the network of partners and researchers working on similar issues across regions.

This evaluation did not assess the final proposals prepared by the participants as they were handled by the donor. However, feedback from the experts who were hired by the donor indicated that the quality of the proposals improved substantially to the extent that the proposals were ready to be considered for funding.

Several key lessons emerged from the implementation of the e-learning program described in the case study above.

Understand the capacity needs of the learners: Designers of the e-learning programs need to fully understand the background and the needs of the learners in order to increase the relevance and the utility of the program. Matching the skills needs with the content could optimize the learning speed and make the learning process effective.

Make the learning program user friendly: Adult learners are increasingly becoming accustomed to internet based learning platforms. Yet efforts to increase the user friendliness of the e-learning modules can help reduce the fear of the technology and focus on the content of learning. Highly complex algorithms to retrieve, store, and use course contents reduce the frequency of access and hence the efficiency of learning.

Cater to different types of learners: Learners have varying degrees of absorptive capacity depending on their ways of learning. While it is difficult to distinguish the type of learners during the e-learning program, one way to reach out to all learners is to provide a variety of learning activities that cater to different types of learners. Modules should help visual and auditory learners. Those who prefer hands-on experience should be equally accommodated to achieve maximum results through the learning programs.

Encourage and reward online exchanges: Self- motivation remains a major challenge in an e-learning program. There is need for constant attention to inclusion of activities that bring the participants to the course and reward them for their efforts. This is a particular challenge in the courses that do not offer credits that could be used towards larger accomplishments such as a diploma or a degree. Involvement of the course moderator to engage the participants effectively throughout the course is an important success factor. Encouraging online exchanges among the participants that keep them actively engaged in the course will be essential for the success of the program.

Schedule flexibility: Flexibility of course schedule is crucial for the learners of different speed to catch up with the course content offered at various points in time. Extended time may be important for the participants who are already engaged in professional activities during the day. Spreading the course assignments throughout the course period gives an opportunity for the moderators to be in regular touch with the participants and increases the active engagement of the participants.

Commitment of the course moderator: Commitment and enthusiasm of the course moderator will determine the pace of the activities in an e-learning program. Given the communication is mainly through written form, the choice of the words and the style of communication need to exhibit the commitment of the facilitator or the moderator. Experienced moderators have the ability to show such commitment through their communications.

Make additional resources available: Adequacy and variety of learning resources determine the success of e-learning programs. E-learning programs could use the open source learning materials that are made available by other programs as global public goods. Learning the same content from different sources helps learners to understand the difficult concepts much faster.

Mixed approaches to learning: A major objective of distance learning programs is to reduce the cost of learning by allowing participants to stay on their jobs and in their own living environments without disturbing whatever they are doing.. Yet, an element of face-to face interaction can increase the benefits of the learning process multi-fold. However, incorporating the face-to-face element will depend on the availability of resources and the ability of the participants to pay for such an approach.

Sustainability of the approach: A key lesson learnt from the exercise relates to sustainability. This approach of combining e-learning with the face-to-face workshops is more feasible financially when the program is implemented within a country. Regional and global level courses will incur high costs in bringing the participants together, unless the international travel is funded by the donor agency. However, country level programs can replicate the model with participants covering the cost of their travel. A suggestion made by the participants was that the creation of a national level network of learners who could gather during the meetings of their professional association would help in reducing the cost of face-to-face meetings. Finally, the success of the e-learning program depends crucially on the persistence of the participants and their commitment to learning, particularly in the context of poor connectivity due to low bandwidth and other logistics. Thus the choice of participants is a key for the success of the program and the program needs to be demand driven.

Building a new field of research and practice will require a strong cadre of highly skilled senior and junior researchers across fields and disciplines to undertake high quality, policy relevant scholarship. The e-learning course described above is a result of the recognition of the extreme scarcity of interdisciplinary graduate training in field-based feminist research methodologies on gender and security.

The e-learning course on proposal development was offered to potential recipients of research grants from IDRC. The objective of the course was to equip 21 researchers with skills and knowledge of proposal development so that they could raise resources for their own research. A major benefit of developing such skills is to increase the ability of the local researchers to sustain their research interests and skills as well as to prevent the brain drain that results from low utilization of well-trained individuals and low remuneration and research opportunities. Developing skills for proposal writing would help in raising the resources for the research and at the same time reduce the chance of the researcher leaving the research profession or the country due to lack of opportunities. An outcome of the e-learning program was to generate about seven peer-reviewed research proposals on “Young Women’s Political Participation in Middle East and North Africa Region”. The model of combining the e-learning with the face-to-face workshop as described above helped to reach these outputs and outcomes. The workshop organized at the completion of the online course provided a platform to bring together like-minded researchers and helped in establishing a regional network in the issues and areas of common interest leading to the sharing of resources and experiences.

While the use of e-learning as an educational delivery mechanism is still nascent in sub-Saharan Africa (Okonkwo, 2012), experience from the above program shows that it has high potential to reach out to a large number of learners with limited resource costs. However, the problem of slow internet connectivity and difficult access to the internet, at times, frustrate the learners and demotivate them to participate in e-learning (dela Peña-Bandalaria, 2007). This pilot course also provided the lesson that the course should span at least eight weeks in order to allow participants to develop the proposal concurrently as part of the learning process. In addition to the proposal development course, the participants also brought up the demand for courses such as measuring impact, detailed data analysis techniques and methodology, and using econometric and statistical software for data analysis. Further research is needed to identify the best combinations of e-learning and the face-to face program, best mode of delivery, best combinations of reading materials and the discussion sessions, and ways to improve motivation among the distance learners. In this context, the importance of promoting opportunities for developing course contents as open educational resources and using them effectively in the distance education programs cannot be overemphasized.

dela Peña-Bandalaria, M. (2007). Impact of ICTs on open and distance learning in a developing country setting: The Philippine experience. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8(1).

Freeman, R. (2004). Planning and implementing open and distance learning systems: A handbook for decision making. Vancouver, Canada: Commonwealth of Learning.

Fukuyama, F. (2004). Nation building. Ithaca : Cornell University Press.

Gulati, S. (2008). Technology-enhanced learning in developing nations: A review. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(1).

Howell, S., Williams, P., & Lindsay, N. (2003). Thirty-two trends affecting distance education: An informed foundation for strategic planning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 4(3). Retrieved from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/fall63/howell63.html

Johnson, S., & Aragon, S. (2003, Winter). An instructional strategy framework for online learning environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 100.

Leary, J., & Berge, Z. L. (2006). Trends and challenges of e-learning in national and international agricultural development. International Journal of Education and Development using ICT, 2(2).

Mandinach, E. B. (2005). The development of effective evaluation methods for e-learning: A concept paper and action plan. Teachers College Record, 107(8), 1814-1835.

Ogunsola, A. (2010). Face-to-face tutoring in open and distance learning - The Nigerian situation. International Journal of Open Distance Education, 20-29.

Okonkow, C. A. (2012). A needs assessment of ODL educators to determine their effective use of open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 293-312.

O’Rourke, J. (2003). Tutoring in open and distance learning: A handbook for tutors. Vancouver: COL.

Potashnik, M., & Capper, J. (1998). Distance education: Growth and diversity. Finance & Development, 35(1), 42-46.

Smyth, R., & Zanetis, J. (2007). Internet-based videoconferencing for teaching and learning: A Cinderella story. Distance Learning, 4(2), 61–70.

SSRC. ( 2012) . Global Centre for Research on Gender and Crisis Prevention and Recovery. Retrieved from http://www.ssrc.org/programs/global-centre-for-research-on-gender-and-crisis-prevention-and-recovery-cpr/

Taylor, J. C. (2001). Fifth generation distance education. Paper presented at the ICDE World Conference, Düsseldorf, Germany.

UNESCO. (2002). Open and distance learning: Trends, policy and strategy considerations. Paris: UNESCO.

U.N. (1997). Gender mainstreaming. Report of the Economic and Social Council for 1997. New York : Author.

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. ( 2012). Assumptions and challenges of open scholarship. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 166-189.

Course Schedule for the Four Week Online Course

Week One

During this week, participants will be introduced to each other and to the online course. In the first lesson, we will introduce the purpose of research proposal, qualities of successful research proposals, the IDRC proposal requirements, and evaluation criteria for the proposal. The second lesson will provide an overview of how to situate research concept notes within a critical review of relevant literature across disciplines. Based on review of relevant literature and contemporary policy debates, the third lesson will focus on formulating problem-centred and participatory derived research questions and objectives.

Lesson 1: Introduction to Research Proposals

Lesson 2: Analysing the Context and Concept: Reviewing the Literature on Young Women’s Political Participation in Crisis Affected Countries

Lesson 3: Formulating Research Questions and Objectives

Week Two

In the second week, we will begin with the ethical considerations for the research in relation to ensuring access and research permissions, data safety, and security of research and study populations. The fifth lesson will look into key elements needed to present the proposed research design. The sixth lesson will review key elements necessary for describing research methodology, with a focus on data collection.

Lesson 4: Research Ethics

Lesson 5: Research Design

Lesson 6: Method: Data Collection

Week Three

Building on second week lesson, the third week will introduce how to communicate key factors relevant to data analysis in a research proposal, describes you how to create the work plan taking into account every contingencies that may arise in the field, and discusses on how to identify relevant constituencies and dissemination strategies.

Lesson 7: Methods: Data Analysis

Lesson 8: Project Schedule

Lesson 9: Research Results: Outputs, Evaluation, and Dissemination

Week Four

In week four, we will begin with how to present information on staffing, partnerships and project management in clear and concise manner. Lesson 11 will provide you some tips for preparing convincing budgets. The last lesson emphasizes the importance and discusses an art of writing appealing abstract, the very first section of a proposal.

Lesson 10: Project Management and the Research Team

Lesson 11: Proposal Budgets

Lesson 12: Proposal Summary

Participants are further encouraged to use any proposals that they might currently be working on in the completion of lesson exercises or discussion in the forums for advise and suggestions on improvement by the course moderator and other participants. The online course was followed by a complementary 3-day on-site workshop.

Cairo 3-Day Workshop Agenda and Objectives

IDRC Research Initiative on Democratic Governance, Women’s Rights and Gender Equality in the MENA region, Eastern and Southern Africa:

Young Women’s Political Participation

Day 1

9:00-10:00 - Introductions and Welcome

Participants introduce themselves

What motivates you to work in this area of research?

10:00-11:00- Introductions Continued

IDRC, SSRC, and IFPRI

Background on each institution

What inspired each institute to join in this collaboration

Expectations and objectives of this collaboration and workshop

11:00-1:00-Obstacles to Women’s Political Participation – Global Literature and a Local Context

Identifying and comparing trends and lessons learned at the national, regional and international levels

Overview of the literature and comparative debates

Objectives

To take stock of current issues at the global level

To review selected results from recent research

To contextualize the issues and results for the benefit of the current proposals

Main Points

Why a comparative framework matters

1st and 2nd generation research questions: Politics, Participation, Gender, and Youth

General trends and conceptual frameworks

What do research teams want to see happening in their own countries?

1:00-2:00 lunch

2:00-3:30- Women and Political Participation in Eastern and Southern Africa

Overview of the literature and contemporary debates

Presentations and discussion based on the review conducted by participants in the region

Objectives

To address specific issues related to Eastern and Southern Africa

To understand research projects’ context and relevance

To prioritize research questions and identify specific research objectives

To begin a discussion of target users

To have research team members engage one another in active discourse

Presentation and Discussion Format:

Each team will make 15-minute presentations.

These presentations should be based on the literature reviews conducted by each research team in preparation for their proposal development.

If using a PowerPoint presentation, it should be no more than 10 to 12 slides.

The presentations should focus three main topics:

1. The current literature and debates on women’s political participation in the region with particular emphasis on the country (for example, the Malawi Research Team would present on Southern Africa with particular focus on Malawi)

2. Key research findings – What is known from past research conducted on this topic in this particular region/country?

3. Research gaps – What new knowledge is needed in order to increase young women’s political participation in this region/country? How do you prioritize these research gaps?

3:30-4:00 Coffee Break

4:00-5:30 -Women and Political Participation in Middle East and North Africa

Overview of the literature and contemporary debates

Presentations and discussion based on the review conducted by participants in the region

Objectives

To address specific issues related to Eastern and Southern Africa

To understand research projects’ context and relevance

To prioritize research questions and identify specific research objectives

To begin a discussion of target users

To have research team members engage one another in active discourse

Presentation and Discussion Format:

Each team (Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan) will make 15 to 20 minute presentations.

These presentations should be based on the literature reviews conducted by each research team in preparation of their proposal development.

If using a PowerPoint presentation, it should be no more than 12 to 14 slides.

The presentations should focus three main topics:

1. The current literature and debates on women’s political participation in the region with particular emphasis on the country

2. Key research findings – What is known from past research conducted on this topic in this particular region/country?

3. Research gaps – What new knowledge is needed in order to increase young women’s political participation in this region/country? How do you prioritize these research gaps?

Day 2

9:00-9:45-Increasing Young Women’s Political Participation: Conceptual and theoretical models of democratic governance

An introduction to and discussion on the debate on current issues and models

Objectives

To review current conceptual thinking

To highlight key research questions

To facilitate comparability of the proposed research projects

945-10:00 Coffee Break

10:00-11:00 -Increasing Young Women’s Political Participation: Exploring gender mainstreaming through the lens of a gender and crisis prevention and recovery framework

Objectives

To address key issues of gender mainstreaming in Africa and the Middle East in the context of crisis prevention and recovery

To contribute to and build upon the current conceptual thinking surrounding democratic governance and increasing women’s political participation

To facilitate comparability of the proposed research projects

To bring in a global policy environment perspective

11:00-1:00- Research Methodologies and Risk Analysis

Objectives

To review approaches/methodologies

To discuss possible synergies in approaches and methods

To identify challenges and risks in meeting objectives

How do the research teams make methodological decisions based on their risk analyses?

1:00 -2:00 Lunch

2:00-5:00-Strategies for Policy and Change Action

Mini group discussions on expected research results, effective dissemination strategies and the comparability of anticipated outcomes

Objectives

To discuss anticipated challenges and expected research results

How do researchers strategize at local, national, and regional levels?

To identify key stakeholders, targets, and end users at local, national, regional and international levels

To share outreach experiences and review dissemination strategies

To facilitate comparability of the proposed research projects

Making an impact on the ground and developing networks

Youth and the politics of the present

3:30-4:00 Coffee Break

Day 3

9:00-12:00-Two Parallel Individual Project Sessions

Individual Project Discussions

Objectives

To reflect on days 1 and 2

To bring the focus back to the IDRC research project proposal

To discuss weaknesses/roadblocks and brainstorm ways to improve

To identify elements of a comparative framework within the ESA and MENA region

To discuss next steps and review logistics

12:00-1:00-Comparative framework

Identify key threads at sub-regional level

Find commonalities through which research teams can support one another

Discuss weaknesses in proposals that need strengthening

Solidify a core sub-regional network

1:00-2:00 Lunch

2:00 -4:00

Plenary discussion and Concluding discussion(s)