This is a report of the role of Distance education (DE) in enhancing education and training in developing countries. As countries compete in an ever more challenging international marketplace, they recognize the need to continually train and upgrade their citizenry. As national leaders struggle to cope with increasing populations and decreasing budgets, DE can be an additional and often essential tool in accomplishing this goal.

This paper is a case study of the efforts of one college in Vietnam, Fisheries College Number 4, to develop a plan to introduce a small distance education offering to its regular courses. Its purpose was to better serve farmers in remote regions. The first author, Ramona Materi, through her company, Ingenia Consulting, carried out the work on behalf of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), a public corporation created by the Parliament of Canada to help researchers and communities in the developing world to find solutions to their social, economic, and environmental problems. Materi’s assignment was to work with College officials to develop the DE plan and funding proposal.

The paper begins with a brief description of the role of information and communications technology (ICT) in education and development, particularly in South East Asia. It then provides an overview of Vietnam and its current activities in DE. The next section offers a detailed examination of the challenges the College faced in developing a plan for DE on the Internet. The paper concludes with Materi’s personal observations and commentary on lessons learned.

The debate on the role of education and development is complex as the appropriate role of DE, and more specifically the use of DE technologies, in advancing economic and social well being. Commenting on distance education, Chung (1990) notes:

Given the limited human and financial resources available to third world countries, distance education becomes an invaluable tool for development. Through distance education, one teacher can reach an audience of millions rather than only a handful. The cost of distance education can be a fraction of that of traditional formal education, thus enabling limited resources to reach a larger population (p. 64).

Casas-Armengol and Stojanovich (1990) argue that the “rational and well-planned use of new and advanced technologies” in distance education can enable developing countries to break out of offering degrees for social prestige and instead allow “true knowledge development” (p. 133).

Other writers, however, wonder if advanced multimedia technologies are practical for poor countries. As Penalever (1990) comments:

The application of modern technologies will entail an increase in the costs to be borne by the students, which, in turn, will affect their access. It is possible that third world countries will not be able to make use of the “technologically advanced” new modalities of distance teaching, which are being developed at present in industrialized countries (p. 28).

These concerns, though, have been no barrier to the use of interactive DE technology in Asia, as academic conferences throughout the years demonstrate. In 1990, the Universitas Terbuka in Indonesia hosted the “Interactive Communication in Distance Education” conference, at which scholars from DE institutions throughout the region discussed ways to increase two-way interaction between instructors and students. In 2001, another Indonesian conference with the same theme appeared, “Facing Global Competition: Open learning and Information technology: Problems and Promises” (2002), where scholars looked at quality issues in online learning and teaching, and other related topics.

Nonetheless, access to Internet technology varies widely in the region. The Asian Development Bank has prepared a series of reports looking at infrastructure problems and related matters. Countries, like Singapore and Malaysia, have solid structures in place, and others like Thailand and the Philippines are moving towards better connectivity, while others like Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia require major investments to upgrade their technological networks. The majority of these countries, however, recognize the importance of the Internet and the urgency of investing in essential telecommunications infrastructure (Murray, 2003). Thus, distance educators working in the region must plan to deal with a wide range of capabilities when designing programs.

Vietnam is considered one of the poorest and most underdeveloped countries in the world. As the CIA Fact Book (2002) notes: “Vietnam is a poor, densely populated country that has had to recover from the ravages of war, the loss of financial support from the old Soviet Bloc, and the rigidities of a centrally planned economy.” The country was at war from 1945 to 1975, after which it faced an economic embargo until 1990. From 1993-1997, growth averaged 9 percent per year, but it has slowed in recent years because of the recession in the global economy and in South East (SE) Asia. With a population of 78 million, almost 80 percent of the workforce is involved in agriculture and lives in rural areas. In 2000, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita was estimated at US $300 per year.

With respect to education, Vietnam faces several urgent needs. With more than 75 percent of its population under the age of 30, it has numerous new students entering the primary and secondary schooling systems. It also has massive numbers of people to train in new technologies and practical skills to achieve economic development. Less than 25 percent of the total workforce is skilled labour. According to Thai Thanh Son (2001), an analyst working for the United Nations Development Program in Vietnam:

Retraining, upgrading and standardizing working staff in all sectors of the national economy is [urgently required]. Approximately 80 percent of the country’s workforce was originally trained along different lines. Consequently, they are not adequately prepared for today’s economy and they need additional training.

As an example, the Vietnamese government has created Export Processing Zones, to encourage socio-economic development in rural areas. In one zone in Quang Ngai province, an oil refinery complex will need 4,000 engineers and 12,000 skilled workers by 2005. With the current state of education and training, however, the complex will do well to have 5 to 10 percent of that required workforce. Similarly, for lack of qualified Vietnamese personnel, British Petroleum, a multinational working with the Vietnamese government to develop offshore oil, must import engineers and oil field specialists from Thailand. The shortage of skilled workers is endemic across industries outside of the agricultural sector (McTavish, 2003).

Vietnam has been involved in distance education since the 1950s. Faced with swelling numbers of students and needs, the government is beginning to invest more in the sector. In particular, it believes that DE can be effective in promoting human resources training (Son, 2001).

In the mid-1950s, many colleges and universities established units and departments for correspondence training. In the 1980s and 1990s, the government established more formal DE institutions, including the Vietnam Institute of Open Learning (1988), and the Open Learning Institutes of Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh (1990). In 1993, the government established the Hanoi State Open University and the Semi-Public Open University in Ho Chi Minh City. These institutions manage and organize open learning and distance education throughout Vietnam.

In 1998-1999, approximately 800,000 learners participated in some sort of open learning or distance education offering. These included 40,000 undergraduate in-service learners, 10,000 students of in-service secondary vocational education, 100,000 continuing education students, 400,000 foreign language students, and 250,000 people upgrading literacy. Thousands of others participated in seminars and workshops (Global Distance Learning Network, 2001).

Much of the DE offered in Vietnam is print-based. Ha Noi Open University (HOU), for example, has regional learning centres throughout the country. Students receive their materials by mail or pick them up from the centres. HOU also produces audio and video materials for select courses and has videoconference facilities, funded by the World Bank. It has a simple website, and sends emails to the regional centres for basic administrative matters. HOU’s offerings mirror those of most other Vietnamese institutions.

The use of Internet for DE is relatively rare due to such constraints as:

Despite these constraints, Internet usage in Vietnam is growing. Infrastructure problems are being remedied with Asian Development Bank funding, Vietnam plans to install fibre optic networks in the Northern provinces by 2005. The “pipeline” between Ho Chi Minh and Saigon should be double-tracked by the end of 2003 (Chang, 2003). As for language, many young people study English, and it is common in large city cyber cafes to see them chatting for hours online, alternating between Vietnamese, French, and English language forums.

As these problems are resolved, the likelihood of Internet usage for DE is enhanced. Already, Vietnam and Japan have signed an agreement on e-Learning, whereby the Hanoi Institute of Technology, Vietnam’s ’s premier information technology (IT) facility, is working with Japan’s Kyoto University to explore the use of e-learning for IT courses. Such initiatives are likely to continue to expand. The rest of this paper will describe how one college is moving forward to use the Internet as a DE teaching tool (Nguyen, 2003).

Located outside of Ha Noi, Fisheries College Number 4 is responsible for providing college level and continuing education courses to students and workers in the northern provinces of Vietnam. Its courses range from business and accounting to aquaculture, information technology, and food processing technology.

The fisheries sector is important to Vietnam, employing millions of people, contributing four to five percent of GDP annually, and nine to 10 percent of Vietnam’s total exports. The government would like to increase the number of fisheries technicians by 20 percent between 2000 and 2010. The goal is to create jobs for two million people in aquaculture; at present, only 30 percent have been trained. In Vietnam, aquaculture is carried out at home in rural areas, with 45 percent of the workforce comprising women. Because the government sees aquaculture playing a major role in improving the role of women in rural and mountainous areas, the priority need is for worker training in rural areas (Wyne, 2002).

In support of this goal, the College has developed a one-week, in-person short course in aquaculture targeting farmers. Instructors from Ha Noi help locally based staff deliver the course, traveling to learning centres in rural areas. They are away from the college for up to one month at a time. The College has a large area where it houses various species in aquaculture ponds, which are used to train farmers and regular students. As part of the government’s rural development efforts, courses for farmers are offered free of charge. Class sizes range from 45-100 people, with the College offering the sessions two to three times per year.

This current training model places pressure on college staff, learners, and facilities; increasing the number of classes, learners, and teaching locations would only exacerbate the strain. Instructors must travel frequently in rural areas along roads crowded with carts, bicycles, and slow moving trucks, making for long, tiring, and dangerous journeys. Students also face difficult travel conditions and many must also be away from home and family responsibilities for extended periods.

To alleviate these problems, the College approached the Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC), seeking funding for the use of ICT to meet the needs of farmers. The first author was the consultant who carried out the development of a DE plan and funding proposal.

A basic needs assessment revealed the following issues related to the implementation of ICT in distance education:

The College decided to offer learners the option of taking the aquaculture course through DE. It sought to take advantage of current delivery trends in the developed world, which are to use the Internet and other ICT technologies to increase course quality and opportunities for interactivity. The College proposed a blended approach, whereby students would receive theoretical and supplemental information through DE, and the practical portion via face-to-face instruction in the field.

In pursuing this model, the College would be a leader and a pioneer; as mentioned previously, few post-secondary institutions in Vietnam are using the Internet for training purposes, and even then the scope of use is more limited than that which the College is proposing.

The overall objective of the project was to pilot the use of ICT tools in support of DE in rural areas of Vietnam. In addition, the project was designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of blended training as a development educational tool with rural adult learners. More specific objectives include:

The College would establish a DE teaching centre on its main campus, with computers connected to the Internet. College instructors would use this teaching centre to create DE materials for Internet delivery, respond to student inquiries, and conduct research to help them develop courses with the latest scientific and technical information.

The College would set up a second DE centre at its Quang Ninh extension centre. For the pilot course, farmers would still attend classroom and field sessions. In addition, they would receive training in computer and Internet skills, and have access to supplementary materials that College instructors develop. This material would include information on aquaculture theory and techniques, as well as relevant information on Ministry of Fisheries programs.

The technologies the College plans to use include:

Described is an overview of the methodology for the project, developed by the College in conjunction with international advisors. Divided into three phases, the aim of the project is to address some potential pitfalls uncovered in the needs assessment.

In this phase, lasting approximately eight months, the College will work with stakeholders, a local Internet Service Provider (ISP) NetNam, and foreign consultants to develop staff capacity in Internet technology and DE training. It will also set up the distance learning centres. Major activities will include:

The process in the second phase, implementation, lasting approximately 14 months, will consist of:

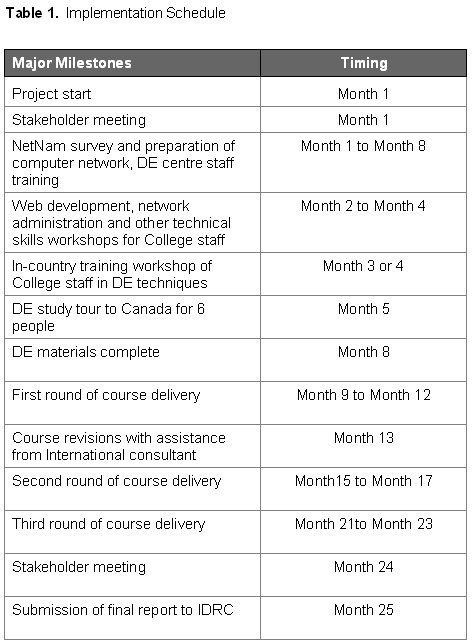

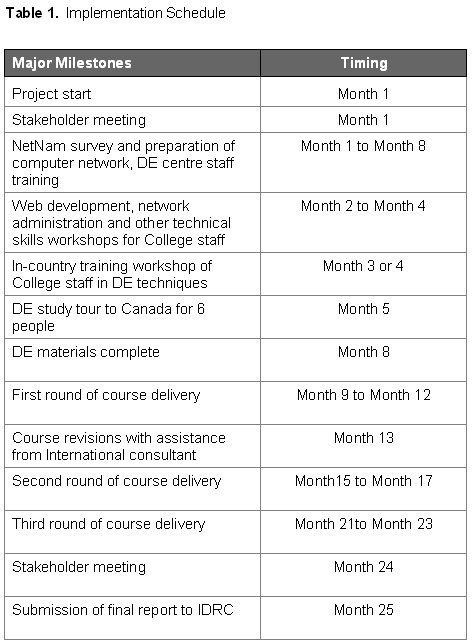

Table 1 shows the two-year project schedule:

The College will undertake several activities to evaluate project quality. The areas it will assess include:

Outputs from the project will include:

In December 2002, the IDRC accepted the College’s proposal and contracted with the College of the North Atlantic, Newfoundland, Canada, to begin implementing the plan. As of April 2003, progress was on schedule, and the College was purchasing computers for its main campus and the provincial extension centre. While aware of the risks inherent in the project, the IDRC believes that the willingness and enthusiasm of the College administration and staff for the project will be enormously helpful in the likely event of difficulties (Lafond, 2003).

In conclusion, the first author found the College Number 4 project to be interesting and satisfying on professional and personal levels. As a part-time Athabasca University student enrolled in the Master of Distance Education program, the author was gratified to put theory into practice. It was professionally gratifying to know that her efforts would benefit others in fundamental ways, since a well-designed program could contribute to basic economic development in poor provinces. Experiencing the warm and gracious hospitality of her Vietnamese hosts, she found it enjoyable to work once again in a cross-cultural environment.

Looking back, the key lessons learned from the project included:

As the project moves along, the first author will keep abreast of its doings, since the IDRC has suggested a midterm and final evaluation of the project. This will be an excellent opportunity for the author to evaluate the effectiveness of the project design and ascertain, once again, how well theory works in real life.

Asian Association of Open Universities. (1990). Interactive communication in Distance Education. Jakarta, Indonesia: Universitas Terbuka.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2002). The World Factbook 2002 – Vietnam. Retrieved April 8, 2003, from: www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/vm.html

Casas-Armengol, M., and Stojanovich, L. (1990). Some Problems of Knowledge in Societies of Low Development: Different perspectives on conceptions and utilization of advanced technologies in distance education. In M. Croft, I. Mugridge, J. S. Daniel, and A. Hershfield (Eds.) Distance Education: Development and access (p. 130-133). Caracas: International Council for Distance Education.

Chang, P. (2003). Personal communication. (February 26).

Chung, F. (1990). Strategies for developing distance education. In M. Croft, I. Mugridge, J. S. Daniel, and A. Hershfield (Eds.) Distance Education: Development and access. (p. 61-66). Caracas: International Council for Distance Education.

Global Distance Learning Network (2001). A Country Report on Open and Distance Learning in Vietnam. Retrieved April 7, 2003, from: http://gdenet.idln.or.id/country/ar_vietnam/CRVietnam.htm

Global Distance Learning Network (2002). Facing global competition: Open learning and technology: problems and promises. Retrieved April 7, 2003, from: http://gdenet.idln.or.id/symposium/program.asp

Chang, P. (2003). Personal communication. (February 26).

McTavish, I. (2003). Personal communication. (Feburary 21).

Murray, S. (2003). Personal communication. (February 25).

Nelson, M. (2003). Personal communication. (February 19).

Nguyen, D. (2003). Personal communication. (February 18).

Nguyen, N. (2003). Personal communication. (February 18).

Penalever, L. M. (1990). Distance Education: A strategy for development. In M. Croft, I. Mugridge, J. S. Daniel, and A. Hershfield (Eds.) Distance Education: Development and access (p. 21-30). Caracas: International Council for Distance Education.

Son, T. T. (2001). Distance education and its contribution to rural development. Retrieved on April 7, 2003, from: http://www.undp.org.vn/mlist/cngd/032002/post11.htm

Wyne, D. (2003). Personal communication. (September 4).