This article presents NKI's experiences with online education from the time the idea was conceived in 1985 to the point when the total number of course enrolments exceeded 10,000 in June 2000. The 15 year period covers three generations. The first generation (1985-1994) was characterised by system development and experimentation with emerging technology. The second generation (1994-96) was a period of transition from the EKKO computer conferencing system, which NKI developed for online education, to Internet systems with text-based user interfaces. The third generation, 1996 to the present, began with the introduction of graphic user interfaces and the World Wide Web (WWW) and is characterised by a vigorous expansion and the introduction of large-scale online education.

NKI is one of the largest nongovernmental educational institutions in Scandinavia. The NKI Group is organised as a non-profit foundation comprising NKI Distance Education, The Polytechnic College (DPH), The Business Training Centre (NA) and NKI Publishing House. It has approximately 350 full-time and 700 part-time employees. The group’s head office is situated in Oslo, and there are district offices in 15 other towns. Altogether the NKI Group has each year a total of around 6,000 full-time and 25,000 part-time students.

NKI Distance Education offers both traditional distance education programs and online programs via the Internet College. Altogether, this constitutes approximately 100 programmes and more than 400 courses at secondary and undergraduate levels, as well as specialised courses for competence development in business and industry. NKI Distance Education employs some 65 full-time and 400 part-time employees. Each year it has around 15,000 active students (about 20 percent of them are now online students) out of a population of 4 million Norwegians. It is recognised by the Ministry of Education and receives government grants covering about 15 percent of operating costs. During the last 15 years NKI Distance Education has developed from a correspondence school to an institution applying the Internet for delivery of a large number of courses. Still, in the year 2000, traditional distance education courses constitute about 75 percent of the revenue and online courses constitute the remaining 25 percent.

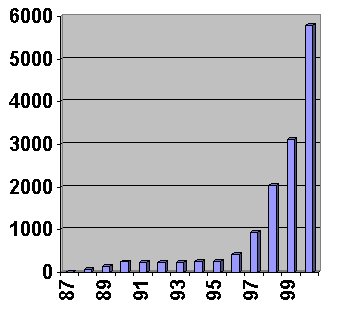

NKI was probably the first European online college, and it has offered distance education online since 1987. Few, if any, online colleges in the world have been longer in continuous operation. NKI has experienced three generations of online education since it started. The first generation system, 1985-1994, was based upon the EKKO computer conferencing system developed at NKI. The second generation, 1994-1996, was Internet-based and the third generation, 1996 to the present, is characterised by Web commitment. The expansion in online enrolments from 1987 to 2000 is shown in Figure 1. In June 2000, the accumulated number of course enrolment exceeded 10,000. In the autumn of 2000, the NKI Internet College had about 75 tutors and 2,500 active students in 15 countries. At the end of year 2000, the NKI Internet College offers more than 30 complete programs and 200 different Norwegian courses online.

Figure 1. Number of course enrolments in online courses from 1987 – 2000

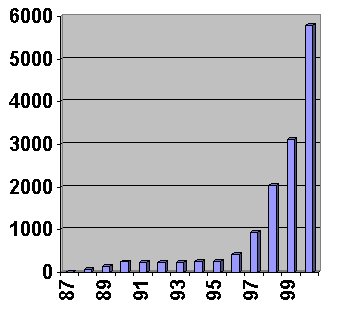

Although NKI Distance Education is one unit in a larger educational institution, it has a large degree of independence and may be viewed as a single mode distance teaching institution. The core competence of the institution is development and delivery of cost-effective distance teaching programmes. The institution has six departments: Academic Staff (including Research and Development), Learning Material Development, Student Counselling and Teaching Administration, Sales Department, Marketing Department, Administrative and Clerical Staff.

Table 1. Budget allocation for year 2000 and number of employees with NKI distance education departments

New courses and programmes are developed by project teams, normally chaired by a representative from the Academic Staff, and including personnel from other departments and external specialists as course authors and consultants. There is a permanent external staff of some 350 part-time tutors coming from other educational institutions, research organisations, and business and industry. Before they start teaching, NKI requires them to complete a “course for tutors” that since 2000 has been offered only online.

NKI Distance Education offers courses and programmes at secondary and tertiary level. Most programmes are equivalent to one semester, one year, or two years of full-time studies. They cover a wide range of subject areas. Some are specially developed courses preparing for careers in business and industry with no parallel in the public school system. Other programmes and courses prepare for state examinations. Courses at tertiary level are either specifically accredited by the University Council or offered in co-operation with The Polytechnic College, a public college or university.

NKI was mainly a correspondence institution till the beginning of the 80s, when videotapes, audiotapes, fax, radio and TV programmes, computer software and laboratory kits, and in some cases, audiographics, satellite and local cable television were introduced – in many cases only as part of experimental and research projects (Rekkedal, 1993). The basic strategy underlying all experiments has been student flexibility, including the possibility of starting at any time and studying with individual progression. This has meant that media suitable for flexible and individual studies have been preferred before media requiring students to meet at fixed times and places. Quite early, the NKI research group understood that computer mediated communication would become an important technology in the future (Paulsen, 1987; Paulsen and Rekkedal, 1988). This is the reason for NKI’s continuous research, evaluation and development of online courses and programmes since 1987.

The NKI Group is legally a non-profit foundation. Financial surplus is kept within the organisation for future developments. Thus, NKI Distance Education is also a non-profit organisation aiming to support Norway’s educational policy as a reputable complement to the public education system. The overall business idea is “to cover needs for competence development by offering courses and programmes for adult learning specifically adapted to the participants’ previous knowledge and skills, place of residence and socio-economic conditions.” (NKI, 1999, p. 3). As a nongovernmental institution, NKI is largely dependent on student fees for its operation, but it also receives some state support. The amount of state money received is based on overall study activity during the preceding four years measured by students’ completion of courses. State financial support covers only 15 percent of the operational costs. As a fee-charging institution, NKI has been devoted to beliefs and values of the service industry, considering students as customers who have all rights to demand high quality services. State accreditation has also required the institution to develop and update a formal system for quality assurance (Ljosà and Rekkedal, 1993; NADE, 1996).

NKI is primarily an effective and efficient distance teaching institution. Although research is not among its main activities, unlike most other nongovernmental distance teaching institutions in Norway, it has established a research department that has maintained a continuous research agenda for 30 years (Rekkedal, 1998). The main aims of the research activities are quality assurance, institutional development, competence building, public relations, and contact with national and international academic institutions. The research projects, in particular, on online education have received considerable national and international funding.

The NKI staff is quite stable. Many employees, and specifically those possessing core competencies in the field of distance education, have worked with NKI for many years. They have learned most of their skills in a “correspondence school” tradition. Generally, the staff is enthusiastic. They know that the organisation’s ability to act effectively is necessary for survival in a competitive market and that success is directly dependent on the knowledge, skills and actions of each individual in the organisation. One manifestation of this culture is probably much less resistance towards change than in most public institutions.

The organisation is dependent on being continuously cost-effective. This means that during the conversion process from traditional distance teaching delivery to effective online delivery there is an absolute need to earn income from existing courses delivered traditionally and at the same time developing new courses and programmes for online delivery. To keep pace with the developing market is a main priority.

The backbone of an efficient large scale distance teaching institution is the computer system for administering students. The student administrative system in NKI has for many years been developed to satisfy the needs of a large scale institution, including an OCR system for bar code registration of assignments, monitoring student progression, distributing new learning materials, and paying tutors. However, the computer system was not suited for serving the online students, as there were no connections between the Internet systems and the administrative systems.

Norway is a highly developed welfare state based on an egalitarian society with a high standard of living. The population of 4.5 million live scattered in a relatively large country. Still, most people live in towns and urban areas and the transport systems are well developed. Technology for computers and telecommunications is generally well developed. According to statistics from Norsk Gallup opinion research in June 2000 [www.gallup.no], Norway has the world’s highest rate of access to the Internet from home (about 50 percent). Statistics show that a majority of distance students come from urban areas where a majority could study similar courses face-to-face. Distance study is preferred for practical and economical reasons (Madsen and Sannes, 1998). Norway has 4 universities and about 30, predominantly public, colleges. In contrast to most other countries, public schools, colleges, and universities do not charge tuition fees.

It has been part of the social democratic political ideal that equal access to education is a human right, and that public education at all levels is free of charge. Although private schools are free to operate, they have generally never been encouraged politically or economically. The general public holds the view that education should be free. However, most political parties have been relatively supportive of private distance education. According to the authors’ knowledge, the Norwegian 1948 Act was for about 25 years the only law in the world that specifically regulated distance education. Since 1975 the government has also supported distance education financially either through direct subsidy of student fees or support to the institutions to reduce fees.

Norway is one of the richest countries in the world measured by average income, gross national output or surplus from foreign trade. Most people have the financial means to pay for private education, but little motivation to do so, as education is considered to be a free service. Distance education is financially supported by the state. This scheme of state funding has resulted in lower tuition fees for the students. However, since 1975 state support to distance education students has continuously decreased from nearly 100 percent to approximately 15 percent in 2000. In addition, distance students may apply for state grants and loans on similar conditions as ordinary students in public and private schools and colleges. Recently, public institutions have been given greater freedom to charge fees for further and continuing education, resulting in more “fair” competition and subsequent over time change in attitudes concerning tuition fees.

Today, there are approximately 15 independent distance teaching institutions accredited by the Ministry of Education. The two largest, NKI and NKS, offer nearly 80 percent of the yearly course enrolments reported by the 15 accredited institutions. However, according to statistics from the Ministry of Education, the number of course enrolments at independent institutions have decreased from a peak of 200,000 in 1976 (Karow, 1977) to less than 100,000 in 1998 (Statistics Norway, 1998; 1999). This decrease in enrolments probably reflects the decline in financial support from the state. As the existing institutions naturally make great efforts to maintain or increase their yearly number of enrolments, the decreasing demand has increased the level of competition. The institutions have broadened their range of subjects offered. Thus, to a larger extent than before the institutions are competing to attract students within the same subject areas.

During the past 50 years the government has taken a number of initiatives to establish public distance education. But these have not succeeded and until recently there has been little competition from public institutions. However, following some governmental reports and white papers during the late 1980s, the government established the Norwegian Agency for Flexible Learning in Higher Education (SOFF) in 1990. SOFF’s main objectives have been to stimulate developments and experiments on distance education at the tertiary level, co-ordinate activities, give some financial support, evaluate activities and recommend future developments. The governmental stimulation through SOFF has led to most universities and colleges becoming interested in distance education, trying out distance education and establishing separate positions and/or departments for distance education. Thus, the level of competition also from public institutions has increased significantly during the last years. Similar initiatives have been taken at secondary level, where public schools have been stimulated and been given more freedom to offer courses on a commercial basis.

NKI has four income earning units. The units have internal co-operation but, to optimise effectiveness and cost-efficiency, are supposed to act independently. They are generally dependent on the central management for IT support, personnel management as well as budgeting and accounting services. Although top management initiates strategic planning, the director of Distance Education has the full responsibility for conducting the strategic planning process. Until 1997 online teaching was included in the strategic planning process as one among many technologies. In 1997, the increasing online activity and the institutional attention to online education reached a level that sparked a separate strategic planning process which resulted in a distinct online education strategy (NKI, 1997).

NKI Distance Education is supposed, both by legislation, governmental requirements and by NKI management, to maintain a quality assurance system with which to control and assess its quality. Student evaluation in different forms is often carried out to gain information about the quality of learning materials, teaching processes and administrative systems.

NKI Distance Education is required to generate a surplus every year for financing central and administrative functions. Investments for future development, such as transforming the organisation from a traditional distance teaching institution to online delivery, have to be financed through the ordinary operational budgets.

NKI Distance Education co-operates closely with the NKI Polytechnic College. Courses and programmes from the Polytechnic College are offered as distance studies through NKI Distance Education. As the Polytechnic College specialises in information technology programmes, its academics and students have been important resources in the development of online teaching. The initiative of the first experiments and the development of the first EKKO computer conferencing system came from the Polytechnic College.

NKI Distance Education is also collaborating with public universities and with some external colleges, secondary schools, and study organisations. One example is undergraduate studies in “Psychology” where NKI organises and operates the online education, but students enrol at the University of Oslo and take the university exams. A similar example is “IT for Teachers” where students take the exams at the Bodø College. NKI also co-operates with study organisations where local organisers arrange face-to-face classes for NKI distance students.

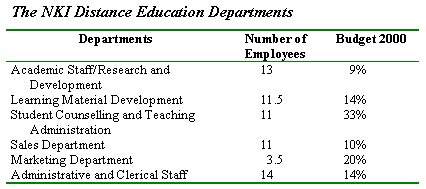

The idea of online teaching, under the name “The NKI Electronic College”, was conceived in 1985 and further developed by research on existing computer conferencing systems such as PortaCom, EIES, and CoSy, and on electronic colleges such as Connected Education and the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute (Paulsen, 1989). The basis of our ideas for establishing the “Electronic College” was largely taken from Hilz (1986). In an early paper we pointed out the following requirements for our virtual school:

During the first two years, the project was propelled by a handful of enthusiasts who devoted much of their spare time to the project. The idea was to use computers to facilitate flexible interpersonal communication in distance education. Students, faculty, and staff could communicate independently of time and space through the college’s central computer. They could exchange written messages both individually and in groups.

Figure 2. The first generatoin system metaphor

The Electronic College needed administrative and logistical support from NKI Distance Education, and academic and technical support from the Polytechnic College. At first, few believed in the project, making it hard to get the necessary support and to integrate the project into the NKI organisation. Gradually, the Electronic College thrived with satisfied students, receiving internal, national, and international recognition.

The first version of EKKO, the computer conferencing software hosting the electronic college, was designed and implemented during 1986. The system was used for the first time, as an optional supplement to on-campus teaching, in the autumn semester of 1986. The first attempt to deliver a distance education course via EKKO was made during the autumn semester of 1987. Two additional courses were introduced the following semester. Since the spring of 1990, the college has offered all ten courses within in the Information Processing Programme every semester. These ten courses constitute the equivalent of a 1 year full-time programme.

During its most intensive period EKKO served more that 3,000 users, including on-campus students, prospective students, active distance students, former students, tutors and administrative staff. The system included an email system, closed and open conferences for administrative, teaching and social purposes, and bulletin boards. During the first generation period the Electronic College delivered more than 1,000 courses with an average completion rate of above 80 percent.

NKI considered the first generation of the electronic college to be quite a success as a distance education system. However, we continuously followed other developments in teaching/ learning methods and software on the market and examined different products, such as CoSy, PortaCom, FirstClass, and the Internet with the aim of developing an improved 'second generation' system. When we had to introduce new solutions because of retirement of the old host computer, we decided to use Internet, email, and the Listserv conferencing system. Since few students had Internet access, NKI also offered modem services to students.

The Internet platform represented in several ways a setback. The interface was still text-based and far from user-friendly. Norwegian characters and email attachments were not supported. On the other hand we got access to many more potential students and online resources.

All the courses and programmes developed after the introduction of the second-generation system were un-paced and without limits on times for enrolment. This solution was chosen as a result of general experiences and student evaluation surveys. “It is a major challenge to develop methods and organisations in distance education based on computer conferencing systems which take care of the students’ need for autonomy and flexibility” (Rekkedal, 1990, p. 92).

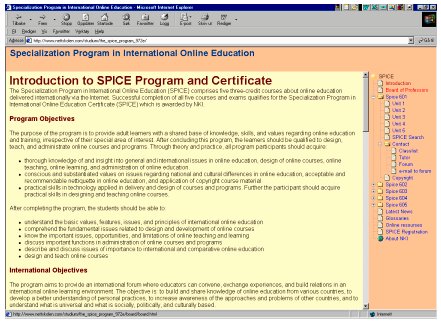

The third generation was introduced with graphic user interfaces and the first Web-based courses in 1996. The Web service could be regarded as a two-level system. The top level, the NKI Internet College homepage [http://www.nettskolen.com] depicted in Figure 3, provides general information about the college such as course descriptions, prices, contract form, contact information, support information, and an article library on online and distance education. The graphical and user-friendly Web interface introduced opportunities such as hyperlinking and multimedia presentations. However, there were also new challenges such as access control and copyright issues.

Figure 3. NKI College homepage

The second level, the program homepages, is password protected and can only be accessed by NKI employees and fee paying students. Figure 4 depicts an example of a program homepage. The course homepages are designed with a set of templates to secure some course conformity. A typical course homepage provides links to each of the study guide units, to the tutor’s email address, to the class discussion forum, to external Internet services and resources, to a course evaluation form, and possibly to multiple choice assignments. The study units are also often designed so that the students can benefit from printing out the material.

Figure 4. Example of a program homepage

There is no doubt that the decision taken in 1996 to base the Internet College on standard Internet servers and client software used by the ordinary Internet user was a sound one. Today the Internet College offers approximately 200 different courses in over 30 complete study programmes secondary and tertiary level. Online course enrolments have nearly doubled every year since 1996 and are budgeted to pass 5,000 in 2000. Still, however, only around 20 percent of the NKI distance students choose online courses. Most of the students live in Norway, but students are now logging into the college from 15 to 20 different countries. The Internet College puts great emphasis on facilitating learning according to the students’ needs, which could be described in the following way. A student may enrol at any time in any of the programmes and courses or personal choice of courses and follow his or her own progression schedule. The College is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The students may choose to study individually or take part in academic discussions or leisure and social communication with fellow students, teachers and alumni. In some courses group activities are obligatory. Concerning the conferences, we have chosen a combination of 'push' (contributions sent as email to all members of a conference) and 'pull' (contributions archived and accessible to all members) technology.

The process of converting the organisation to online course and programme delivery has had a number of consequences. Whether these have been intended or unintended is largely a question of time, as unintended consequences at one time may be intended or actually, if negative, by counteractions be reduced or removed at a later stage.

While NKI believes that online delivery of distance learning programmes, when handled competently, using pedagogically sound practices, should imply a more satisfactory study experience and better learning than correspondence-based individual distance learning, until now NKI has charged the same fees for both modalities. At the same time, online students appear to have higher expectations of service quality, and quantity and quality of communication with their tutors. While earlier distance learning systems had high front-end costs, which could be compensated by lower delivery costs in large scale systems, it seems that high quality online learning might have both high front-end costs and high delivery costs. Thus, it is a challenge to find ways of reducing either development costs or tutor costs. We have not yet found a solution to this problem. During the first generations of online delivery we had the working hypothesis that less emphasis could be put on the pre-production phase of courses. In our experience, this is not a correct assumption if we want the students to be satisfied.

To stay in business, we have had to offer courses in two parallel versions. This has made course development more labour intensive and expensive. Further, as many of the courses are also offered in a “combined education” model, we may also have distance students in local face-to-face classes who have access to the Internet and students who have not. This situation has been difficult to organise both administratively and pedagogically. Thus, online delivery to combined education students has been a problem, and it has been difficult to satisfy the needs of both student groups.

Online delivery means recruiting new tutors. Some of the “old” tutors for text-based delivery have not been interested in online tutoring. On the other hand, delivery online has attracted new groups to distance tutoring. Some online tutors find this way of teaching especially exciting and rewarding. To prepare new tutors, NKI has for many years offered an obligatory training course. Beginning in 2000 this course is offered only online. Thus, tutor training is a necessary element in the process of converting to online delivery. NKI has at any time some 50 prospective tutors in the tutor training course. Because tutor workload is generally perceived to be heavy in online education (see e.g., Paulsen, 1998), it has been difficult in some subjects to recruit competent tutors and to develop pedagogic solutions and administrative software to rationalise and ease the workload for online tutors.

As NKI has been an entrepreneurial institution in online delivery of distance learning programmes, it has been a necessity to engage in field research. By attracting external funding from national and international bodies, the research activities made it easier to recruit competent personnel, led to co-operative engagements with national academic and research institutions, and made us an attractive partner in a number of national and EU projects (e.g., specifically concerning survey, analysis and evaluation of online learning visits). See [http://www.nettskolen.com/alle/in_english/cisaer/index.html]. It has also given publicity through published articles, research reports, conference papers and media coverage.

This case study describes the long process of converting a distance teaching institution with a long tradition from delivery of correspondence education with some multimedia components into an institution adapted to online delivery based on the rapid development of the Internet, WWW and other computer and telecommunication technologies. There is no doubt that there has been a transformation of the institution’s systems, practices, and competence and skills of employees, thus affecting the entire organisation. In undergoing these changes, support of the top management has been essential. Adaptation to new technologies has had to occur while the organisation and personnel under change have had to maintain their old and new modes of delivery.

It is not possible to isolate a few important causes for the relative success of the NKI Internet College. It is probably more correct to claim that NKI has made many sensible choices and few major mistakes. However, the twelve causes listed below have all contributed to the success:

The fact that we consider we have had reasonable success in transforming the organisation from a traditional distance teaching institution to an institution adapted to deliver Internet-based distance education, does not mean that we do not face a number of further challenges. Many issues still remain unresolved or are only partially resolved. Probably the most important challenge is to develop methods and teaching strategies to fully exploit the possibilities of the Internet, related to varying learning needs and styles of different students. We have much to learn about how to design instructional programmes. Student learning activities based on this new medium must be designed to achieve optimal outcomes for different kinds of learners in different subjects with different aims and objectives. Satisfying both the individual student’s need for flexibility and needs for collaborative learning in a social group is also a great challenge. We also have to search for better solutions concerning tutors’ functions and efficient management of their time as tutor costs can easily become higher than allowed by the fees charged. Students expect learning material on the Internet to include multimedia elements. There is a need to find ways of developing multimedia material that is both learning-efficient and cost-effective. We need to refine the administrative system for online education and achieve complete integration with the general student administrative system of NKI.

Hilz, S. R. (1986). The Virtual Classroom. Building the foundations. New Jersey: New Jersey Institute of Technology.

Karow, W. (1977). Informationen. Privater Fernunterricht in 16 Landern. Ubersicht und Vergleich. Berlin: BBF.

Ljosà, E., and Rekkedal, T. (1993). From external control to internal quality assurance. Background for the development of NADE’s quality standards for distance education. Oslo: NADE. Retrieved December 6, 2000 from: http://www.nettskolen.com/alle/forskning/17/tallinn.htm

Madsen, B. E., and Sannes, J. (1998). Effekter av fjernundervisning ved de tilskuddsberettigede fjernundervisningsinstitusjonene. Trondheim: NVI.

NADE (1996): Quality standards. (The Norwegian Association for Distance Education). Oslo: NADE. Retrieved December 6, 2000 from: http://www.nettskolen.com/alle/forskning/18/kvalen1.htm

NKI (1997). Motorvei til morgendagen. Plan for utnyttelse av Internett i fjernundervisning 1997-98 – fra eksperimentelle smàskalaforsøk til industriell storskaladrift. [internal document].

NKI (1999). Strategic Plan 2000-2002. Bekkestua: NKI. [internal document].

Paulsen, M. F. (1987). In search of a virtual school. Technological Horizons in Education Journal, 15(5), 71 – 76.

Paulsen, M. F. (1989). En virtuell skole. Del I. Fundamentet i EKKO-prosjektet. Bekkestua: NKI/SEFU.

Paulsen, M. F. (1998). Teaching Techniques for Computer-Mediated Communication. (Doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, 1998). Dissertation Abstracts International, A 60/01, AAT 9915916.

Paulsen, M. F., and Rekkedal, T. (1988). Computer conferencing: A breakthrough in distance learning, or just another technological gadget? In D. Sewart and J. S. Daniel (Eds.) Developing distance education (p. 362-365). Oslo: ICDE.

Rekkedal, T. (1990). Recruitment and study barriers in the Electronic College. In M. F. Paulsen and T. Rekkedal (Eds.) The Electronic College. Selected articles from the EKKO Project (p. 79-105). Bekkestua: NKI/SEFU.

Rekkedal, T. (1993). Practice related research in large scale distance education, Experiences and challenges. In Research in Distance Education – Present situation and forecasts. Umeà: University of Umeà, Sweden.

Rekkedal, T. (1998). Quality assessment and evaluation. Basic philosophies, concepts and practices at NKI, Norway. In H. Rathore and R. Schuemer (Eds.) Evaluation concepts and practices in selected distance education institutions. ZIFF-papiere 108. Hagen: FernUniversität. Retrieved December 6, 2000 from: http://www.fernuni-hagen.de/ZIFF/rekked.htm

Statistics Norway, (1998). Aktuell utdanningsstatistikk. Voksenopplæring i Norge. Nøkkeltall 1998, 5/98. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Statistics Norway, (1999). Aktuell utdanningsstatistikk. Voksenopplæring i Norge. Nøkkeltall 1999, 6/99. Oslo: Statistics Norway.