This article examines open-distance learning in Nigeria and the role it plays in personal, community, and national development. Following consultation with existing literature, a qualitative survey was conducted using questionnaires, interviews, and participatory experience. Although particular emphasis was paid to the Nigerian context, the findings in this article may be regarded as reflective distance education experiences elsewhere in Africa. Clearly, education is the key to human development and progress. It is essential to bring about changes in attitudes, values, and behaviour. Used ethically, distance education may enable people to make informed choices about their present life and future. Moreover, these assertions have been credited to many scholars and institutions at one time or the other. The question here, however, is: To what extent are these assertions true of education, and more especially of those individuals benefiting from open and distance learning in Nigeria? This and more incisive issues constitute the substance of this article.

Keywords: distance education; personal development; community development; national development; Nigeria

The purpose of this article is to introduce readers to the subject of open and distance education and its role in development. From the perspective of Capability Approach Theory, which stresses a developmental approach to education, attention will be paid to the historical antecedents of distance education in Nigeria, the relationship between distance education institutions and the world of work, linkages between open-distance education and development, the intervention of international agencies, and the emergence of the University of South Africa (UNISA), as well as the INADES-Formation Network (http://www.sdnp.undp.org/sdncmr/subweb/cminade4.htm).

The United Nations Development Programme (1991) describes development as a process that goes beyond the improvement of quality of life: it encompasses better education, higher standards of health and nutrition, poverty reduction, cleaner environment, increasing access to and equality of opportunity, greater individual freedom, and the facilitation of a richer cultural life, which are all truly desirable ends in themselves. By breaking the cycles of deprivation and hopelessness that are the first obstacle to every kind of development (United Nations Development Programme, 2003) the UN Development Programme’s aims in developing countries is to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger. Schultz (1961) stated that education not only improves individual choices available to mankind, but an educated population provides the type of skilled labour necessary for industrial development and economic growth. Dreze and Sen (1995), however, argued that development should be viewed from various approaches. By contending that a “rights-based approach” to improving access to education provides the basis for a comparative assessment of natural progress, Dreze and Sen succinctly anchored their theoretical approach on human rights and capabilities. They further stated that the intrinsic human value of education, which include the capacity of education to add meaning and value to human lives without discrimination, make it a key component central to universal human rights. In sum, education is the key that unlocks and protects the full spectrum of human rights.

When discussing development from the Capability Approach, we assert that development occurs when people are more able to achieve what makes their lives valuable to them. What people value will vary from one individual to another and may include such ideals as being well fed and nourished, achieving a sense of self-satisfaction and self-respect, being literate, being able to do things better, or earn a better living. Thus, the Capability Approach shifts the goal of development from mere income or economic growth as ends in themselves, to that of growth of people and enhancing the quality of the human condition. Viewing development from this perspective implies that it can be seen as a process of expanding the real freedom that people enjoy. Education, in this larger sense of term, serves as a tool people can use to achieve the level of freedom that they feel is intrinsically valuable, as well as achieving rudimentary levels of knowledge acquisition (e.g., beginning with literacy and basic arithmetic), which serves as a functional key to greater educational development. Education and development policies based on Capability Theory are judged to be successful if they enhance people’s individual capabilities, whether or not they directly affect income or economic growth.

Calvert (1986) wrote that distance education helps extend the market for education to clientele who have not been previously served. The problem of unsatisfied demand for education versus actual supply of educational services contributed to the acceptance, growth, and implementation of distance education programmes in Nigeria as a means to bridge the gap between demand and supply.

The history of distance education in Nigeria dates back to the practice of correspondence education as a means of preparing candidates for the General Certificate in Education, a pre-requisite for the London Matriculation examination. This practice was described by Bell and Tight (1999), and echoed by Alan Tait (2003), who said:

. . . the University of London has been termed the first “Open University,” because of this move, students all round the world, but principally within the British Empire and its dominions, were soon looking for tutorial support to supplement the bare syllabus they received on registration wherever they lived (www.undp.org/info21/public/distance/pb-dis2.html).

In this sense, Nigeria was not left out of the opportunities provided by University of London. Omolewa (1976) reported records that showed a handful of Nigerians, as far back as 1887, enrolled for the first time in the University of London matriculation examination as external students studying through correspondence, and without enjoying any established formal ties to that educational institution. Omolewa (1982) also noted that in 1925 several Nigerians, among them Eyo-Ita and H.O. Davies, passed the London Matriculation Examination. Later, E.O. Ajayi and Alvan Ikoku both obtained University of London degrees in philosophy in 1927 and 1929 respectively, and J.S. Ogunlesi obtained a degree in Philosophy in 1933 (Omolewa, 1982). Access to such educational opportunities at a distance contributed immensely to these individual’s productivity, which in turn resonated in the innovations they subsequently demonstrated in their teaching methodology at the St Andrew’s Teachers College, Oyo (Aderinoye, 1995). Besides these individuals, a significant number of Nigeria’s early educated elites were products of the British correspondence distance education system. Indeed, in spite of the establishment of a University College in Ibadan in 1948, many of its academic staff still passed through the higher degree programmes of the University of London as distance learners, enabling them to combine work with higher degree programmes. They thus acquired the advanced skills and knowledge needed for teaching and research at a time when the College was introducing its own higher degree programmes.

With the emergence of many conventional higher institutions in Nigeria, most of which once were based on purely correspondence modalities, distance education still constitutes an integral part of these institution’s educational offerings (Aderinoye, 1992). Institutions in Nigeria that offer distance education include:

Education is inherently a developmental process. Indeed, it can be said that if the expertise necessary for expansion of distance education programmes had not been available, the education policies and developmental issues in place today would have excluded many Nigerians and Africans. Most pioneers of distance education were products of the British correspondence system and the London matriculation exam. In the absence of domestic higher institutions in Nigeria prior to 1948, the nation’s first students learned through the distance education modality and eventually graduated to become valuable resource persons whose ground breaking work kick-started the establishment of Nigeria’s first schools and institutes of higher education which, in turn, served as springboards for national development. These “pioneering experts” constituted the original core of administrators and educators that supported educational planning, teacher education, policy formulation, and developmental initiatives.

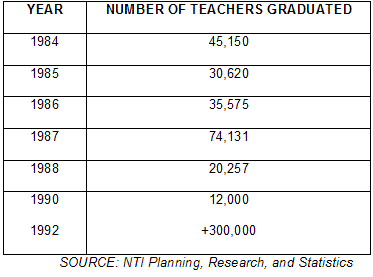

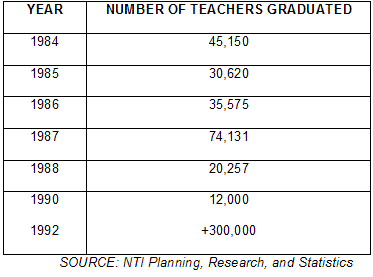

Archived records from these distance institutions reveal that Nigeria’s teaching and educational system, which clearly faced an acute shortage of teachers during the introduction of the Universal Primary Education programme in 1976, and later the Universal Basic Education in 1999, were unquestionably strengthened through the introduction of new teachers produced via ODL modalities. Table 1 shows data gathered through the planning and research department of NTI, which revealed the growing number of graduates produced by that institution alone.

Table 1. NTI Teacher Graduates, 1984 to 1992

Over a period of eight years, the total number of primary education teacher graduates rose from 45,150 to over 300,000. In two short years alone, between 1990 and1992, the NTI graduated 21,000 Certificate in Education holders. This figure compares with the combined total of 58,000 teachers graduated by the nation’s 58 conventional colleges of education (Aderinoye, 2001). The NTI’s Pivotal Teacher Training Programme, designed to support the introduction of the Universal Basic Education scheme introduced in 1999, produced 19,025, 20,800, and 15,587 qualified teachers for years 2000, 2001, and 2002 respectively (NTI, 2003). These activities of NTI have helped to maintain stability, quality, high rates of retention, and have reduced the dropout rates at the basic level of education across the country.

In a follow-up study, which tracked the whereabouts of a randomly selected population External Studies Programme graduates of University of Ibadan (n = 100), revealed that 15 graduates went into private business, while 60 remain in active teaching. It was established, during the course of this follow-up investigation, that eight of the 15 graduates are now successful business women, whose children are now enrolled in university. This finding suggests that a solid appreciation of the importance of education plays in personal and community development, has been passed on to these women’s children. Five of the seven men went into active politics, two of which are occupying the position of State Commissioners presiding over the affairs of education, local government administration, and chieftaincy matters. While the remaining two men serve as secretaries of community development union. The remaining 25 graduates are engaged in income generation activities, through which they have been able to become employers of others.

Another programme that has contributed to rural transformation through ODL is the University Village Association Rural Literacy Programme. Supported by the British Council, this project provided to the local community audio taped learning materials used to augment outreach programmes delivered to 17 adult learners over a period of 18 months. Three face-to-face sessions each week, two hours in duration, were augmented by these pre-recorded audio tape lessons and distributed to learners, allowing for additional learning to take place at a pace, time, and location convenient to them. These audio taped cassettes provided learners with information on current best practices on how functional literacy (e.g., targeting farmers, governance, women, and health issues) has helped to positively transform the lives of those living in Nigeria’s rural areas. While face-to-face literacy lessons were used to provide interaction with facilitators, the use of audio taped cassettes proved to be an important auxiliary learning tool, which were closely monitored for pedagogical effectiveness. When looking at the qualitative aspects made in a 2000 doctoral study, Laoye (2000) revealed that two graduates of the rural literacy programmes served as community association secretaries, while five graduates served as local government councillors, and two served as customary courts judges. In qualitative terms, Laoye’s study reveals that, apart from helping elevate their communities’ living standards, the personal living standards of these graduates had likewise improved. Moreover, these graduates were monitoring and facilitating progress of their children’s education. As such, this developmental “ripple effect” has helped sustain the project, even after the British Council withdrew their support. Today these communities continue to achieve their goals and recruit new pools of learners from the local neighbourhood.

As outlined above, the link between education and development informed the direction and policies of continuing interventions of development agencies like the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Commonwealth Of Learning (COL), British Council, Literacy Enhancement Assistance Program (LEAP), and others. These international agencies have assisted Nigeria (and the African region in general) in the development and training of distance education institutions and their staff. It is on record that UNESCO and the COL lent their expertise in the establishment of the NTI, at a time when Nigeria faced an acute shortage of qualified teachers (Ansere, 1982). Institutions in other African nations that have also benefited from international support include: the Sudan Open Learning Organisation (SOLO); various teacher training and tertiary institutions in Gambia, Zambia, Ghana, and Mozambique, through the introduction and use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for distance learning delivery; and the launch and continuing support for the Virtual University in Kenya. The University Twinning and Networking Scheme (UNITWIN) was established in 1992 following the decision of the General Conference of UNESCO. Today, the UNESCO Chair is the main source of exchange programmes taking place between the developing and developed institutions. Support for various capacity building programmes for distance education institutions across Africa are likewise underway. For example, in 1998 the Department of Adult Education, University of Ibadan, became one of the beneficiaries of the UNESCO Chair on the Application of Information Communication Technology to Adult and Non-Formal Education, which as its official title suggests, is currently focused on the application of ICT to adult and non-formal education. This ongoing work has facilitated the development of the capacity of academic staff of the department. Finally, specific mention must be made of the activities of the following international agencies:

The Commonwealth of Learning (COL) started its intervention through a fellowship programme to staff of African universities. In 1990, to increase his knowledge of ODL, COL sponsored the participation of M. O. Akintayo to the COL/ British Council visiting fellowships programme. Chris Okwudishu of the Centre of Distance Learning, University of Abuja, similarly visited institutions in Canada under the same programme. Some senior officers of various ODL institutions were likewise assisted in the formulation of programme proposals. Among such institutions were:

COL has also assisted in the development of the capacity of West African experts in ODL. In 1992, COL sponsored a training workshop for experts from Gambia, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, with experts from Tanzania and South Africa serving as resource persons. COL also organized another capacity building workshop in programme planning and management for similar group in 1994 in Badagry, Nigeria. With COL’s assistance, the West Africa Distance Education Association (WADEA) was likewise inaugurated at NTI, Kaduna, Nigeria (COL, 1994, p. 18).

An early programme of COL for the South African sub-region (Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa) under the expert guidance of Professor Peter Kinyanjui, continues to advance distance education in other regions of Africa. This is evident in the reliance of other open and distance learning institutions in other parts of Africa on South African experts.

Similarly, UNESCO, apart from providing technical advice for the establishment of the NTI in 1976, organized a workshop on “course writing” for distance education course developers in Abuja in June 2001, in which more than 300 course developers from the West Africa sub-region participated.

The devastating effects of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/ AIDS) on Nigeria and other African nations’ workforce, and most especially on the region’s teachers, not to mention the alarming increase of those living with HIV/ AIDS, necessitated the development of a process of prevention designed to mitigate the impact of this pandemic. To this end, UNESCO signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the NTI to establish the Preventive Education Unit. This MOU covers funding for the preparation of NTI staff and other Nigerians distance education experts in the use of education as a mechanism to change behaviour. The project was launched with the establishment of a unit and the development of curriculum guide and training manual for distance teachers working at NTI. Thus, NTI became the first academic institution in the African sub-region (Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa) to use ODL in the promotion of preventive education to educate people about the transmission and prevention of HIV/ AIDS. NTI, via the development of such ODL materials, is therefore proactively contributing to slowing the spread of HIV infection leading to AIDS. It is anticipated that these valuable teaching resources will be adopted and shared with other educators and experts working in the African sub-region.

One such initiative is the Literacy Enhancement Assistance Programme, a collaborative project funded by USAID and the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Education. Focusing on the states of Kano, Nasarawa, and Lagos, this literacy enhancement programme seeks to improve the ability of Nigerian children to read and write, as well as to master basic arithmetic by the end of their primary schooling years. Employing an innovative combination of interactive radio instruction and teacher training, literacy and basic arithmetic skills are being taught at the grassroots level in the community and its classrooms. Since this programme’s inception, primary students living in the three states targeted in the programme scope, have shown a dramatic improvement in the reading and arithmetic skills. Clearly, FM radio programmes are improving students’ oral and written English skills. It is anticipated that by the end of the first project cycle, hundreds of Nigerian pupils will benefit through improved basic literacy and arithmetic skills, thereby arming themselves with the basic education necessary to kick-start and maintain developmental processes at the grassroots level (e.g., learning about HIV/ AIDS prevention to name one life-sustaining benefit).

Reflecting on where, when, and how distance education has influenced development in Nigeria and Africa brings us to some examples of collaboration and cooperation in distance education. Having analysed the nature, concept, and linkages between education and development and how developmental agencies have helped to establish and nurture distance institutions throughout Africa, it is instructive to examine the influence these educational initiatives have had on the development and growth of individuals, and how such growth has translated into opportunities that have reshaped and bettered individuals’ immediate lives and their communities.

Reflecting on the Nigerian situation reveals the high degree of influence distance education initiatives have had on personal, community, and overall national development. Nigeria can now boast of capable and competent teachers working in its education sector. Nigeria’s distance learning institutions also continue to contribute immensely to the provision and improvement in the quantity, quality, and overall capacity of education managers and school administrators necessary to lead the nation’s educational system. In addition, more than 300,000 primary school teachers enrolled in the NTI, have gone on to successfully earned their Teacher’s Grade II Certificate. NTI has similarly registered serving teachers in its Nigeria Certificate in Education, and the Pivotal Teacher Training programmes, thereby improving the quality of those teachers already working in the field. Having since qualified, these teachers have not only contributed to the increase in school enrolments across Nigeria, they have also increased the quality of education and thus contributed to higher student retention rates (Ojokheta, 2000).

The power and growing use of information and communication technologies and the resulting trend towards globalisation have reduced the world into that of a small village (McLuhan and Powers, 1989). Distance education remains the primary mechanism for the information-driven age, a tool that is bridges the gap between developed and developing communities. It serves as an avenue for developing intellectuals at all levels of their educational journey and facilitates a pedagogy for enhancing learning of both learners and teachers. When used to supplement distance education programmes, information communication technology – the technical medium through which people send and receive messages, acquire knowledge, and learn about new things that add value and context to their lives – can play a positive role in contributing to more egalitarian growth of the global community. People now have access to many different forms and channels of communication including e-mail, e-learning, tele- and video-conferencing, virtual learning, and virtual libraries, to name just some of the more common applications.

A process of social transformation has begun to take place in Nigeria, and those less fortunate, if given adequate access and opportunity, can and do benefit from the establishment of tele-centres within less privileged communities. Today, a process of social transformation is taking place as more and more individuals are striving to be become a part of an emerging “learning society,” a society that at the grassroots level – and arguably where it is most needed – has been brought about by the power of open learning initiatives. Thus, we are moving gradually from the exclusive, closed system mode of “privileged” access to education, towards a more inclusive educational model, which supports and is reflective of UNESCO’s goal of Education For All for the 21st Century. Through various initiatives, such as those undertaken by UNESCO, COL, the British Council, the Literacy Enhancement Assistance Program, and others, the gap between education and the world of work that many developing countries have experienced in the past (and which was initially exacerbated by the integration of new technologies into almost every sphere of professional activity) is now being greatly narrowed. Distance education in Nigeria and throughout the continent of Africa is helping to democratise and spread knowledge even to those living in the most remote, marginalized, and isolated communities. Clearly, this has helped individuals to acquire basic literacy and arithmetic skills, and in some instances even obtain certification in higher education degrees, as well as a multitude of broad-brush education objectives targeting whole populations (e.g., governance skills, life skills, AIDS education aimed at preventing and reducing its spread, improved farming techniques, etc.). At the level of higher education, distance education in Nigeria has offered greater access to many people who would have been previously been denied access to educational opportunities based on where they live and work, poor economic circumstances, social status, etc.

Early graduates of Nigeria’s and Africa’s distance education systems helped pave the way for the much needed educational reforms, development of economic plans, and the establishment of political frameworks that characterize the transition that most African countries are undergoing today.

In economic terms, distance education has helped to produce a better skilled workforce, which in turn has led to the growth and development of both local and national economies. Typically, graduates of distance education programmes find it easier to participate in the economic mainstream. Even older individuals, who after their retirement have chosen to engage in academic upgrading, have gone on to become small business owners/ managers, an educational ripple-effect that has helped enhance the development and growth of both local and national economies.

In terms of development, the worth of distance education must not only be measured simply from what a given individual can contribute towards community and national development. It must also be measured in terms of the changes or improvement such an individual enjoys as a result of the skills and knowledge they have learned and acquired. A dangerous reality, however, is that Africa is clearly facing a “brain drain syndrome,” wherein academics travel abroad to continue their study. A research study conducted by the South African Institute of International Affairs, and published in the September 2003 issue of the Electronic Journal of Governance and Innovation, revealed that: “recruiting agencies abroad, on a South African Internet search engine, found 20,000 hits, while a global engine found 1,040,000 hits with thousands of agencies specifically targeting African Professionals to work abroad,” (e-Africa, http://www.wits.ac.za/saiia). This online journal article explored the implications of the brain drain syndrome on the continent: “At a time when Africa most needs its skilled professionals, the continent is experiencing a steady, de-habilitating brain drain caused by aggressive professional recruiting agencies, personal ambition, and the substantial wage gap between the developed and developing world.” The good news is that an organisation known as “African Recruit,” funded by the Commonwealth Business Council (CBC), has started Job Fairs to recruit Africans studying abroad for jobs back in Africa (Herbert, 2003). In this capacity, the CBC has acted as an employment agency searching for talents to reverse the Diaspora.

The initial problem created by mass movement of intellectuals of African descent to developed countries, is now turning into a blessing. African experts, many of whom have returned home, have started ploughing back their skills and knowledge gained abroad into the development of their native communities and countries. As such, Africa is now beginning to witness the beginning of a “Brain Trust” rather than “Brain Drain.” The cross fertilization created by this newly emerging Brain Trust, however, must be sustained through incentives and improved infrastructure designed to prevent frustration and regret of those intellectuals and highly trained individuals returning home.

Some Nigerian distance education experts who have, at one time or the other, contributed to the development of other countries include: Jones Akinpelu who in 1996 returned to establish and develop the Centre for Continuing Education, University of Botswana. During his six years in Botswana, he developed courses that were strategically in-line with the needs of the people of Botswana, as he assisted in the training of middle level workforce needed for the development of Botswana’s rural areas. In doing this, Akinpelu made a request for more capable hands from Africa’s pool of intellectuals. In response to his call, Gbolagade Adekanmbi, who earned his PhD in distance education from the University of Ibadan in 1992, joined Akinpelu in the task of Botswana’s nation building. Now a Professor Emeritus in the University of Ibadan, Akinpelu is back home to shape research in Nigeria with innovative ideas.

Michael Omolewa brought international acclaim to himself, the Department of Adult Education, University of Ibadan, and his country, Nigeria, when he won the UNESCO Chair on the application of ICTs to Adult and Non-Formal Education for his department in 1998. This Chair has helped the University of Ibadan’s staff to achieve in goals of institutional and personal capacity building. The use of ICT has now led to the establishment of an International Network of Academic Partners that spans the globe.

In 2000, Michael Omolewa and Gbolagade Adekanmbi, along with the author, under the sponsorship of the UNESCO Office in Nigeria, collaborated with other African intellectuals, in a research study of distance education institutions in Africa (Omolewa, 2000). The outcome of this collaborative research study now serves as fertile resource material, for those venturing into the discipline of open and distance education in Africa.

Another distinguished Nigerian distance education expert is Olugbemiro Jegede who, in 2001, returned home to Nigeria to re-establish the National Open University, which as mentioned earlier, had been closed since 1984. Prior to this, Jegede lived in Hong Kong and Australia, and the wealth of experience he brought home from those two countries has advanced the course of the distance education system in Nigeria. The first admission exercise of the National Open University, for example, admitted more than 32,000 students. Through his work, Jegede has proved that open and distance learning is not only cost effective, it is also a most appropriate avenue for widening access to education, especially to those most marginalized and poorest populations in the world.

Distance education in Africa and other continents has been instrumental in lowering illiteracy rate, and more importantly turning about “dropout rates” into “drop-in rates.” For example, in the African countries where the INADES-Formation Project of Jesuits Organization has taken root (Siaciwena, 2000), many subsistence farmers, village women, community leaders, and adults have gained valuable education, expertise, and knowledge, which they have subsequently applied towards the transformation of their local communities. The INADES-Formation programme, launched in 1962, was modelled after the radio-based Canadian and Indian Radio Farm Forum and focused on Africa nations such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Cote d’Ivoire (Omolewa, 2000). In scope, the INADES-Formation Programme covers the development of reading materials in agriculture, health, and community civic education for adult learners, and is combined with the use of facilitators who lead discussions and disseminate information via radio. Government policies in Kenya, Tanzania, and Mali have been broadcast to the grassroots through radio, thus producing a citizenry that is more informed about government programmes available to them.

The Sudan Open Learning Organisation (SOLO) undertook a comprehensive re-orientation of untrained teachers in the Republic of Sudan in 1998. In October 2001, a meeting with the Director of SOLO, representatives of the Sudanese Ministry of Education, and selected members of the community, described the contributions of the SOLO programme:

These initiatives have contributed immensely to the education, social, and economic development of the Sudanese people – particularly those living in the war free states (UNESCO, 2001).

Human resource development has equally benefited from the first distance university in Africa. The University of South Africa (UNISA), established in 1873, has contributed to the emergence of many distance education institutions throughout Africa, and has assisted in developing the capacity of distance education experts across the continent.

In addition to the integration of HIV/ AIDS preventive education into the NTI programme discussed above, distance education has helped to reduce discrimination and stigmatisation faced by those living with HIV/ AIDS. The NTI programme strives to achieve this objective through the broadcast of public education programmes via radio, television, community theatres, posters, classrooms, etc. Such broad-brush programmes have empowered illiterate individuals as well as neo-literates (i.e., those who have engaged in such distance learning systems as the University Village Association), to acquire information and knowledge on how HIV/AIDS is transmitted and how it can be avoided. Details on essential care and support services for those living with HIV/ AIDS are also included in educational material developed for adult and youth (adolescent) learners currently attending the organisation’s open school system.

This article has briefly touched upon the interplay and linkages between open and distance learning and its influence on development. Due to limitations of its focus and intent, this paper has not examined critical issues militating against the effective translation of policies to action. Clearly, there are many ongoing challenges of putting words and policies into action, particularly for ODL experts who are working to enhance and strengthen ODL research, capacity building, and the educational infrastructure, which are all essential ingredients for realization of the Capability Approach Theory described above. Given such challenge, experts working in this area need to remain united in their efforts in the building of a sustainable educational infrastructure.

Aderinoye, R. A. (1992). Retention and Failure in Distance Education: The Nigeria Teachers Institute experience. Unpublished PhD Thesis. The Department of Adult Education, University of Ibadan.

Aderinoye, R. A. (1995). Teacher Training by Distance: The Nigerian Experience. In John Daniels (Ed.) Proceeding of the 1995 ICDE Conference. Birmingham, UK.

Aderinoye, R. A. (2001). Alternative To Teacher Training. In H. Perraton (Ed.) Cost Effectiveness in Teacher Training. Paris: UNESCO.

Akintayo, M. O. (1989). Investment in University Education and the Problems of Unsatisfied Demand. Journal of Andragogy and Development, 1(1) 88 – 95.

Ansere, N. (1982). The Inevitability of Distance Education in Africa. In J.S. Daniel, (Ed.) Learning at a Distance: A World perspective. Alberta, Canada: Athabasca University.

Bell, R., and Tight, M. (1999). Open Universities: A British Tradition? Society for Research into Higher Education. Birmingham, UK: Open University Press.

Calvert, B. (1986). Facilitating Transfer of Distance Courses. Paper presented at the 8th World Conference on Development and Social Opportunity, Delhi, India: Open University Press.

Common Wealth Of Learning (1994). A Compendium of Activities: Canada. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning.

Dreze, J., and Sen, A. (1995). India Economic Development and Social Opportunity. Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

Herbert, R. (2003). Brain Drain vs Brain Trust in East Africa. The Electronic Journal of Governance and Innovation 1. September 6/ 8. Retrieved December 3, 2003 from: http://www.wits.ac.za/saiia

INADES Formation Network (n/d). Retrieved December 4, 2003 from: http://www.sdnp.undp.org/sdncmr/subweb/cminade4.htm

LEAP (2003). Literacy Enhancement Assistance Program: Mid-project assessment.

McLuhan, M., and Powers, B. (1989). The Global Village: Transformations in world life in the 21st century. Oxford University Press: New York.

Ojokheta, K. O. (2000). Analysis of Selected Predictors for Motivating Distance Learners Towards Effective Learning in some Distance Teaching Institutions in Nigeria. Unpublished PhD Thesis. The Department of Adult Education, University of Ibadan.

Laoye D. (2000). A Study of the Impact of UNIVA Rural Literacy Programme on the People of Oyo State. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Ibadan.

Omolewa, M. (1982). Historical Antecedents of Distance Education in Nigeria, 1887-1960. Adult Education in Nigeria, 2(7) 7 – 26.

Omolewa, M. (2000). Directory of Distance Education Institutions in Africa. (Ed). Abuja: UNESCO.

Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human Capital. American Economic Review, 51, 1 – 17.

Siaciwena, R. (2000). Case studies of non-formal education by the Distance and Open Learning, UK. University of Zambia: Commonwealth of Learning and Department of Foreign International Development.

Tait, A. (2003). Reflections on Student Support in Open and Distance Learning. United Nations website. Retrieved December 3, 2003 from: www.undp.org/info21/public/distance/pb-dis2.html

UNESCO (2002). Sudan Basic Education Sector Study. UNESCO: Paris

UNESCO (2003). Education in the context of HIV/AIDS. UNESCO: Abuja

United Nations Development Programme (1991). Development Report 1975. Retrieved December 4, 2003 from: http://www.undp.org/

UNESCO (2003). The University Twinning and Networking Scheme (n/d). Retrieved December 4, 2003 from: http://www.unesco.org/education/educprog/unitwin/