|

Deon Harold Tustin

University of South Africa

Outside an academic setting, telecommuting has become fairly popular in recent years. However, research on telecommuting practices within a higher education environment is fairly sparse, especially within the higher distance education sphere. Drawing on existing literature on telecommuting and the outcome of a valuation study on the success of an experimental telecommuting programme at the largest distance education institution in South Africa, this article presents discerning findings on telecommuting practices. In fact, the research builds on evolutionary telecommuting assessment methods of the direct or indirect effect (work based) and affective impact (emotional) on multiple stakeholder groups. This holistic approach allowed for comparative analysis between telecommuting and nontelecommuting academics with regard to the impact of telecommuting practices. The research reveals high levels of support for telecommuting practices that are associated with high levels of work productivity and satisfaction, lower levels of emotional and physical fatigue, and reduced work stress, frustration, and overload. The study also reveals higher levels of student satisfaction with academic support from telecommuters than nontelecommuters. Overall, the critique presents insightful findings on telecommuting practices within an academic setting, which clearly signal a potential for a shift in the office culture of higher distance education institutions in the years to come. The study makes a significant contribution to a limited collection of empirical research on telecommuting practices within the higher distance education sector and guides institutions in refining and/or redefining future telecommuting strategies or programmes.

Keywords: Telecommuting; nontelecommuting; working from home (WFH); working from office (WFO); open distance learning

Since Nilles (1975) first defined telecommuting as «a type of working model wherein the employee, with some form of telecommunications device (most often a computer with some form of modem) works at a location other than the traditional centralised office,» the magnitude of research on this human resource practice has expanded considerably. Leading salient research on the international front specifically features investigations on the impact of this phenomenon on individuals and organisations. However, much of this past research is largely limited to the private sector. On the one hand, this suggests that telecommuting in the public sector has hitherto not been as widespread as in companies within the private sector. Alternatively, it can be assumed that there is insufficient information to allow for any pragmatic view on the extent to which this phenomenon affects higher distance education employees and institutions. Consequently, it seems reasonable to question whether the public sector, and particularly the open and distance higher education sector1, is suited to such work practices. Existing literature reveals that research to measure the potential for and impact of telecommuting practices on academics and higher distance education institutions is fairly sparse and largely limited to a few international examples. In this regard Athabasca University (Canada’s Open University) published a literature review in 2006 on the potential benefits and shortcomings of telecommuting for academics as well as latent opportunities and challenges presented by telecommuting to open and distance education institutions. Although valuable, this research highlights the potential, rather than the actual impression, of telecommuting on academics and distance education institutions. The fact that the collective work of Athabasca University, as published by Ng (2006), largely resembles the outcome of earlier research chiefly conducted in the private sectors of the United States and the United Kingdom, presented sufficient rationale for conducting a local innovative empirical research study on telecommuting practices in the higher distance education sector of South Africa. Furthermore, the need for a contemporary study of this nature was motivated by the evolution of information technology and the potential for the distance education sector to benefit from these IT developments that present an ideal platform for telecommuting within an academic work environment where the practice of distance learning and research is most likely to benefit from prospective individual and institutional rewards stemming from telecommuting. By introducing a telecommuter programme in 2007 (Unisa, 2011), the University of South Africa (Unisa) is indisputably on the forefront of testing the potential benefits of telecommuting practices in an open distance learning environment. For the first time since the telecommuting experiment was implemented, this article reports on the effects of the telecommuting programme on individual workers and the institution. It stands to reason that as the leading and largest open distance education institution on the African continent (Unisa, 2013), the selection of this institution as the investigative research unit for this evaluative research study was an obvious decision.

Besides the original description of telecommuting by Nilles (1975), exploratory research on telecommuting shows many common conceptions of this phenomenon. In this regard the following selected definitions provide a broader understanding of the concept (Yamini, Balakrishnan, Nguyen, & Lopez, 1997; Fitzer, 1997; Igbaria, 1998; Federal Communications Commission, 2003; Martinez, 2004; Brown, 2010; Ipsos, 2011; Mid-America Regional Council, 2013; Wikipedia, 2013):

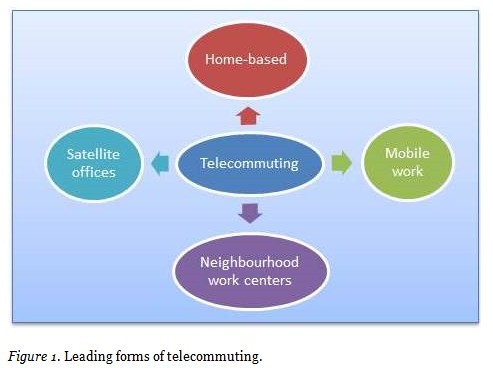

To further distinguish between the de-localisation of work, Figure 1 outlines the main forms of telecommuting as cited in the work of Pinsonneault and Boisvert (1999).

A more extensive exposition of the four main forms of telecommuting follows below:

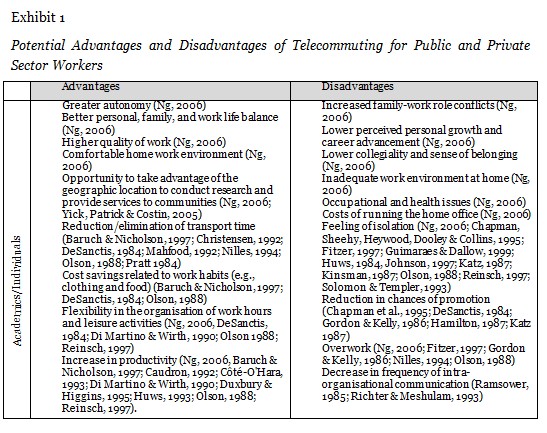

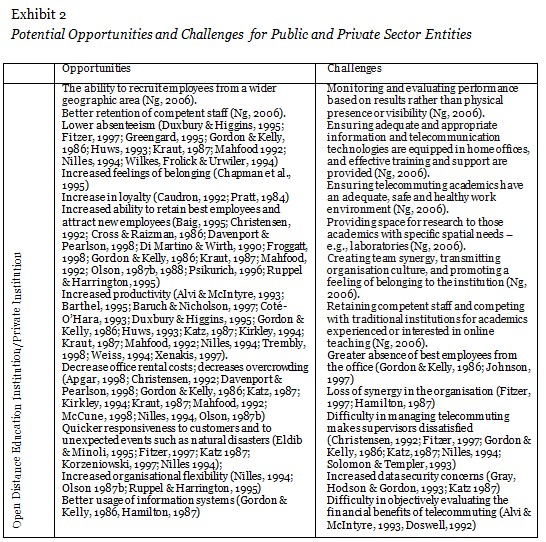

Clearly, telecommuting is not restricted to any one particular form and is not limited to working from home on a full-time basis. Despite this awareness, the South African telecommuting baseline study was limited to measuring the impact of part-time home-based telecommuting as the telecommuting type tested by Unisa. However, prior to reflecting on the outcome of the study, the discussion proceeds with a holistic overview of the potential impact of telecommuting on individuals and organisations to set a sound methodological research foundation for telecommuting. In the absence of similar local research, this synopsis is based primarily on past international research on telecommuting practices within the private and public sectors. These are summarised in Exhibits 1 and 2.

Exhibits 1 and 2 display the plethora of previous, mostly international, research on telecommuting. However, the synopses also affirm a clear lack of similar local research and present sufficient rationale for an original baseline evaluation study for South Africa.

Most past models and theories about telecommuting have concentrated mainly on the telecommuter’s experiences and perspective. In fact, much of prior research on telecommuting has been weakened by two assumptions, namely that telecommuters form a homogenous group and that telecommuting involves only the telecommuter (Bailey & Kurland, 2002; McCloskey & Igbaria, 2003). Also, aligned with the views of Bailey and Kurland (2002), Cooper and Kurland (2002), Golden (2007), Duxbury and Neufield (1999), Fritz, Narasimhan, and Rhee (1998), and McCloskey and Igbaria (2003), few studies have examined the potential impacts of telecommuting holistically, or investigated it from a nontelecommuter and/or student perspective and how this practice affects work outcomes and student satisfaction. With the foregoing as background, this article reflects on the aim, scope, and outcome of the first higher distance education telecommuting study in South Africa that was conducted among both home- and office-based academics, managers of academic departments, and students who received academic support from part-time (home-based) telecommuting academics and/or full-time (office-based) nontelecommuting academics.

With the aforementioned in mind, this research study included four distinctive interdependent key stakeholder groups for which separate research goals and instruments were designed. The specific study objectives for the relevant stakeholder groups are clarified in the subsections below.

This subsurvey was conducted among senior telecommuting academics (professors and associate professors), having been officially granted permission to work part-time from home. More specifically, this substudy aimed to determine telecommuting academics’ experiences and perspectives regarding the working from home (WFH) initiative.

This subsurvey was conducted among two office-bound academic groups. Firstly, the study targeted senior academics (professors and associate professors) that are office-based (nontelecommuters) and who are employed in the same department as an academic working from home. The primary aim of this secondary study was to establish the attitudes and perceptions of onsite staff regarding telecommuting and to determine the perceived effect (work impact) and affect (emotions/attitudes) of telecommuting on office-based workers. Secondly the study also targeted onsite staff employed in an academic department without an academic WFH. Overall, the nontelecommuter study aimed to provide insights into some of the organisational impacts of telecommuting and the implications for nontelecommuters.

This subsurvey was conducted primarily among the supervisors of senior academics (professors and associate professors) who were granted permission to work from home on a part-time basis. The aim of the study focusing on line managers was to determine the perceptions of supervisors of the impact of telecommuting on the staff morale of on- and off-site workers and the operations of the department. To allow supervisors whose departments do not host an academic WFH an opportunity to voice their opinions on the WFH initiative, this subpopulation segment was also included in the line manager’s study.

This subsurvey was conducted among under- and postgraduate students regarding their satisfaction with academic support offered by telecommuting academics (professors and associate professors) and nontelecommuting (office-based) academics working in the same department and lecturing similar or dissimilar modules to those lectured by academic telecommuters.

Whereas a census approach was used to conduct the surveys among academic staff members, a judgemental sampling approach was used to select students to participate in the student satisfaction survey. The judgemental approach largely reduced nonresponse errors that could have had negative consequences for the entire study. Consequently, it was logical to use the academic departments hosting an academic telecommuter as basis for constructing the sampling unit (academic departments) and sampling element (staff and students) frames for the study. More specifically, this approach supported constructive research participation by relevant key stakeholder groups.

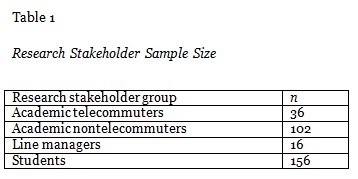

Table 1 displays the sample size for each research stakeholder group who participated in the telecommuter evaluation study. It is important to note that only 33 academic departments hosted senior academic telecommuters who formed the basis for the investigation. In total, 76 Unisa academics telecommuted during the trial period of which almost half participated in the study. In total, 154 academics and 156 students were included in the study.

After constructing the research instruments for the various survey groups, these were transformed into web-based survey formats. For the surveys among the academic groups, an email invitation was sent to all sampling elements, requesting them to retrieve the questionnaire via a web link and to submit the survey once completed. The academic surveys were administrated in conjunction with the student satisfaction survey conducted over a two-week survey period.

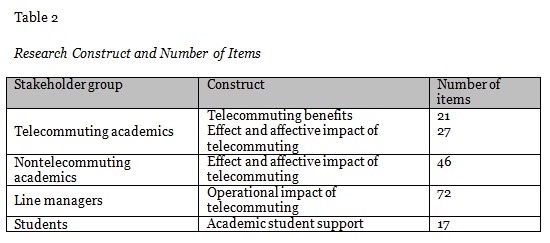

The research instruments designed for all four participating stakeholder groups mainly used a 5-point agreement rating scale for a selection of predetermined statements. The number of variables for each stakeholder group for selected constructs is displayed in Table 2.

It is important to note that participation in the research study for all stakeholder groups was voluntary and depended on participant consent. All participants were informed of the purpose of this research, the confidentiality with which information was received, dealt with, and stored, the right to terminate participation, and what to expect from the interview.

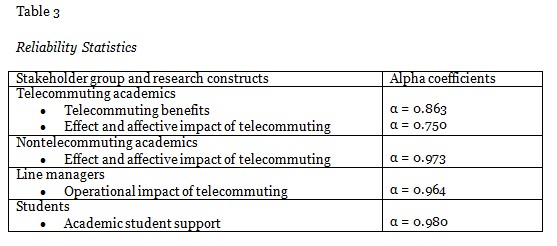

Once the electronic data for all four surveys were captured, the data were edited and cleaned for data analysis and interpretation purposes. All analysis was conducted using the SPSS software statistical analysis package. The analysis also included data validation, the outcome of which is summarised in Table 3. More specifically, Cronbach’s alpha was used as a tool to determine the internal consistency of items in the telecommuter survey instrument to gauge its reliability.

In general, alpha coefficients (α) range in value from 0 to 1 and may be used to describe the reliability of factors extracted from, among others, scale questions (i.e., rating scale: 1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). The higher the score, the more reliable the generated scale is. Nunnaly (1978) and Kline (1999) have indicated 0.7000 to be an acceptable reliability coefficient but lower thresholds are sometimes used in literature. The fact that all Cronbach alpha values exceed the 0.7000 threshold in Table 3 therefore presents sufficient evidence that the listed telecommuting constructs in the four subsurveys are reliable future predictor variables. Also, the overall consensus and consistency of responses across all four different stakeholder groups further support the reliability and validity of the survey findings.

The perceptions and experiences of telecommuting and nontelecommuting academics, managers, and students are analysed in this section essentially in a descriptive analysis format.

This section reveals the outcome of the survey among telecommuting academics.

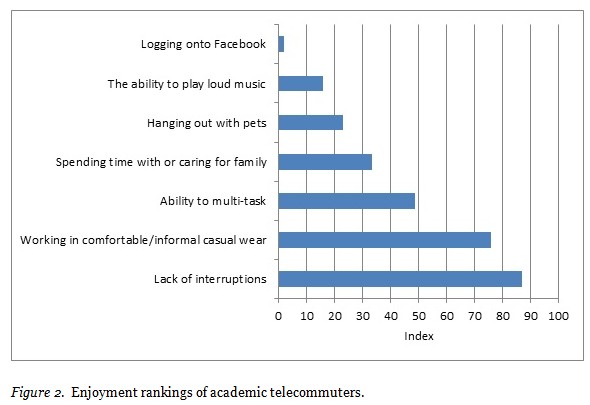

In an introductory section, telecommuting academics were requested to rate aspects that they enjoy most when working from home. These ratings were transformed into a single enjoyment index of which the final result is displayed in Figure 2.

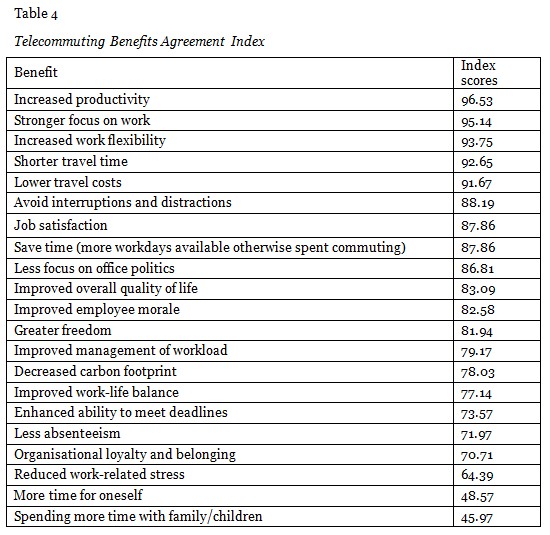

Figure 2 shows that telecommuter academics appreciate telecommuting as this practice presents ideal opportunities for fewer work interruptions and to work in comfort or multi-task. The fact that all academic telecommuters indicated that they are extremely (80.6%) or somewhat (19.4%) satisfied with working from home further affirms high levels of pro-telecommuting sentiments. In fact, when analysing the claimed benefits experienced by academic telecommuters, it is evident that telecommuting increases work productivity, concentration, and flexibility. These views are displayed in Table 4, which summarises the outcome of the levels of agreement with the benefits of telecommuting experienced by academic telecommuters. The analysis shows the agreement index scores for the respective telecommuting benefits compiled from the agreement rating scores of academic telecommuters ranging from totally disagree (rating = 1) to totally agree (rating = 5). It is important to note that scores closer to ‘100’ represent relatively higher levels of agreement.

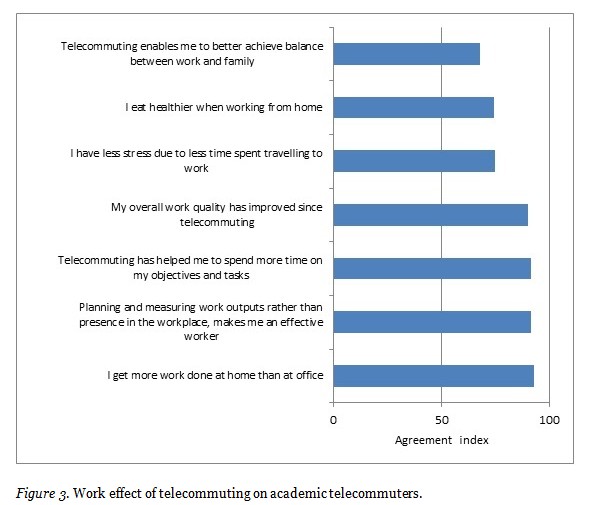

In general, academic telecommuters confirmed that they get more work done and concentrate better at home than at the office, which also contributes to the improvement in overall work quality and healthier (eating and lowered stress) workers. The work-related effects of telecommuting practices that echo these encouraging findings are displayed in Figure 3.

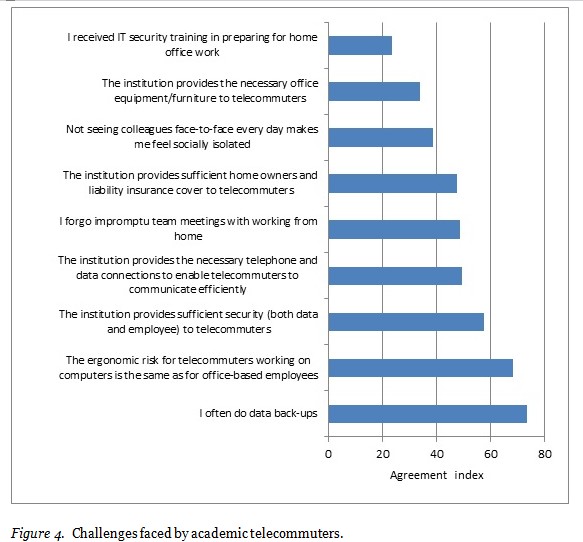

Despite many benefits experienced by academic telecommuters, 76.2% also indicated that the major challenge that they experience is network connectivity to allow digital connection. A further 19.0% of respondents cited the lack of office equipment as a major impediment to telecommuting while 4.8% mentioned that bad posture, as a result of working at makeshift home offices, makes telecommuting less attractive. Social interaction with colleagues at work was also cited by most academic telecommuters as a key factor missed most about not working at the office. The challenges posed by telecommuting to telecommuters are summarised in Figure 4.

The key findings emerging from the academic telecommuter survey presented sufficient evidence of high levels of support for telecommuting practices within a true open distance learning environment. Experienced senior academic staff clearly articulated that telecommuting practices are very beneficial for creating a productive, dedicated, economical, flexible, and satisfied workforce. Also, telecommuters seem very positive about telecommuting as a mechanism to ease work stress and afford more valuable time with family members. However, key challenges remaining for open distance education institutions who wish to expand telecommuting practices are more dedicated attention to improved network connectivity as well as security, insurance, and infrastructure support aspects relevant to telecommuting.

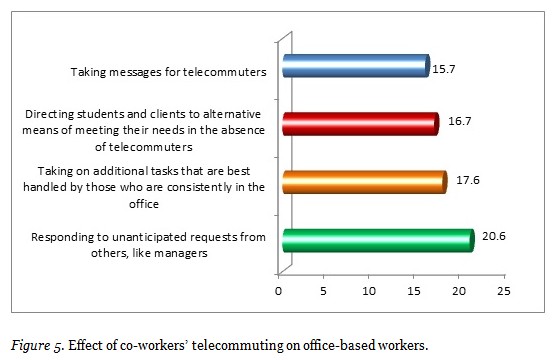

This section reveals the outcome of the telecommuter survey among nontelecommuting academics. When focusing on this stakeholder group, it is important to note from previous international research that telecommuting may change the scope and amount of work of those remaining in the office (see Kugelmass, 1995; Gordon, 2006; Reinsch, 1997; Chapman, Sheehy, Heywood, Dooley, & Collins, 1995; Harrington & Ruppel, 1999). To determine the effect of telecommuting on the workload of nontelecommuting (office-based) staff, a total of over 100 office-based academics participated in the telecommuter study. These academics were requested to reflect on the affective impact and effect of telecommuting practices and to indicate whether they experienced any additional work responsibilities in cases where telecommuting colleagues are absent from the office. Figure 5 reflects the expanded work responsibilities experienced by just more than half (57.5%) of the office staff.

It is clear from Figure 5 that approximately a fifth of office workers have to respond more frequently to unanticipated requests from other staff like managers due to telecommuters being absent from the office. Approximately one in every 10 office staff indicated that he/she has to take messages for telecommuters (15.7%) or direct students/clients in the absence of telecommuters.

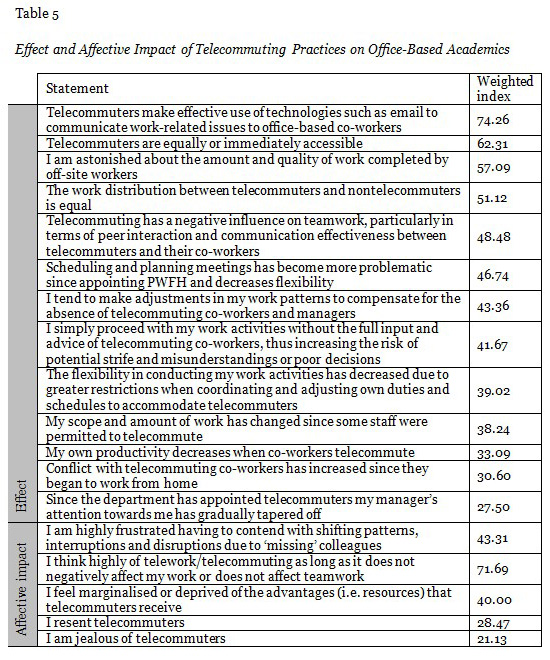

The key section of the research questionnaire measured the perceptions of office workers regarding telecommuting practices. Office-based workers were requested to indicate their level of agreement with 46 predetermined statements using a 5-point Likert response scale where 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree. For analysis purposes, the ratings of respondents were transformed into average agreement indices that are summarised in Table 5 according to the effect (work based) and affective impact (emotional) of telecommuting on office-based workers. Clearly, most office-based academics are content with the access to and productivity of telecommuting academics while some are fairly indifferent about the impact of telecommuting on the workload of office-based workers, teamwork, and shared work responsibility. It would seem that this impartial stance has not roused significant resentment or jealousy of telecommuters among office-based workers. In terms of the effect of telecommuting, office-based workers also have not experienced significant adjustments to their own work schedule, workload, or productivity since the introduction of telecommuting practices in academic departments.

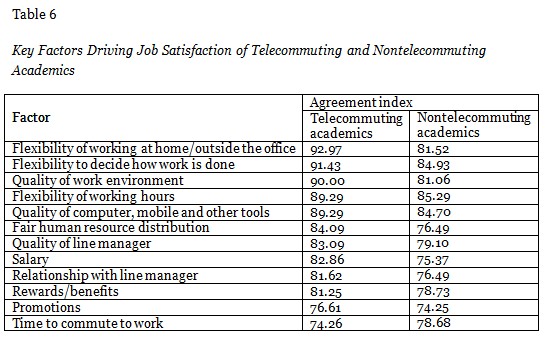

To begin with the comparative analysis between telecommuting and nontelecommuting academics, Table 6 firstly displays the magnitude of the agreement indices for the key drivers of job satisfaction for both academic groups.

It is clear from the rank-order analysis presented in Table 6 that flexibility of working at home/outside the office, flexibility to decide how work is done, and the quality of the work environment are the key determinants of job satisfaction of both academic groups. In turn, rewards/benefits, relationship with line manager, promotions, and time to commute to work are among the least important determinants of job satisfaction.

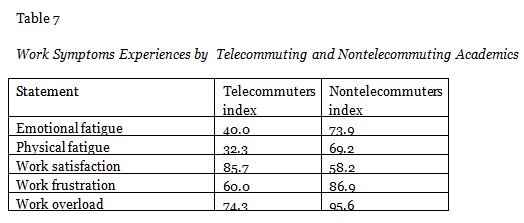

A further key finding emerging from the telecommuting study is that telecommuting academics generally seem more productive and happier than nontelecommuters and also tend to experience lower levels of fatigue and work frustration. The comparative indices shown in Table 7 for the work symptoms experienced by telecommuters and nontelecommuters clearly illustrate these pertinent findings.

The findings displayed in Table 7 closely resemble a 2012 USA (TeamViewer®, 2012) study indicating that employees in WFH arrangements, whether part- or full-time, report less emotional and physical fatigue than on-site workers. When reflecting on productivity in particular, it is also evident from the 2011 International Ipsos Telecommuting Survey that 70.0% of respondents confirmed that telecommuters are more productive than those who work at the office (Ipsos, 2011). Respective figures for Argentina (topping the list) and Japan (bottom of the list) were 77.0% and 44.0%. Internationally, the average proportion of respondents that regard telecommuters as more productive stands at 65.0%.

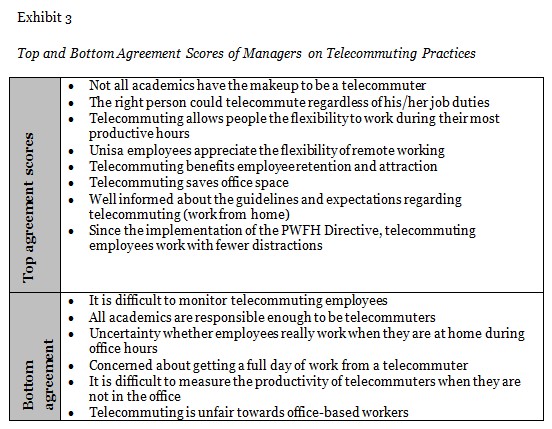

The core of the research instrument designed for line managers/supervisors was devoted to a series of predetermined statements related to the operational and employee impact of telecommuting. Against this background, supervisors were requested to supply their level of agreement with 72 different statements where 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree. Items recording the highest and lowest agreement scores among line managers are displayed in Exhibit 3.

From the analysis presented in Exhibit 3, it is clear that the physical absence of telecommuters presents a fair measure of challenges to managers in terms of monitoring the work performance of telecommuting staff. Also, managers are clear in their views that not all academics are suitable for telecommuting. Despite this view, line managers confessed that telecommuting practices are most likely to result in more flexibility and dedicated employees.

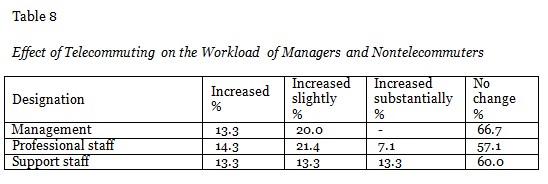

To measure the effect of telecommuting on the workload of managers, professional and support staff, the survey also requested line managers/supervisors to indicate whether the workload across these different staff categories had increased or remained unchanged since implementing telecommuting practices in the academic department. The outcome of this research finding is presented in Table 8.

It is clear from Table 8 that approximately 60% of the managers/supervisors indicated that telecommuting had no significant impact on the workload of nontelecommuters. One in every five line managers indicated that the workload of management (20.0%) and professional staff (21.4%) had increased slightly. Just more than 10.0% of line managers indicated that the workload of support staff had increased substantially as a result of telecommuting. Most importantly, Table 8 shows that two-thirds of managers experienced no change in their own workload.

It was also evident from the line manager survey that telecommuting is an ideal strategy to retain and attract staff. Line managers were also of the opinion that telecommuting practices reduce stress and that telecommuters are as trustworthy as office-based workers. Line managers were also confident in their views that there is no resentment between telecommuters and nontelecommuters and that telecommuters are not necessarily seen as more loyal than nontelecommuters. From a managerial perspective, telecommuting does not impact severely on the management ability of line managers and does not require significantly more supervisory oversight, time, or monitoring than required for nontelecommuters. Finally, line managers were of the opinion that telecommuters are readily available and that their absence from the office does not have any significant impact on the workload of nontelecommuters.

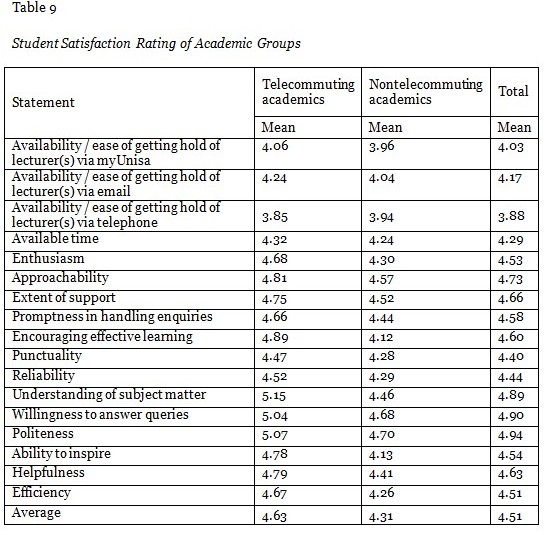

This section reflects on the outcome of research findings among the 156 students evaluating a total of 97 different modules lectured by telecommuting and nontelecommuting academics. It is important to note that a filter question was used to determine whether students had made any academic enquiries. This precondition served as qualifier to allow students to participate and rate the groups on 17 predetermined academic support criteria where 1 = extremely dissatisfied and 7 = extremely satisfied. The information contained in Table 9 presents a holistic comparison between the student satisfaction ratings for the two academic groups.

Although both academic groups show above-average ratings for all items, it is clear from Table 9 that student satisfaction with telecommuter academics is higher for all except one of the evaluation criteria (availability/ease of getting hold of your lecturer(s) via telephone). To establish whether the differences between the rating scores for the two professor groups are statistically significant, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was conducted. The outcome of this test showed statistically significant differences only for the following items:

Against this background, it can be concluded at a 95% level of confidence that telecommuting academics are more effective in encouraging learning and have a better understanding of subject matter and ability to inspire students. This outcome is to be expected as only academics at professor and associate professor levels with at least three years’ work experience qualified to telecommute at Unisa during the telecommuting trial period.

The key findings and trends emerging from the Unisa telecommuting baseline study provide sound motivation to expand telecommuting practices at open distance higher education institutions. This recommendation is also supported by the work of Bélanger (1999), Pinsonneault and Boisvert (2001), and Potter (2003) that identified improved productivity, loyalty, job satisfaction, flexibility, employee morale, retention and attraction as major reasons for the international growth in telecommuting. Key challenges that will most likely be faced by open distance higher education institutions include the following:

Higher distance education institutions have clearly become part of the transformation to introduce telecommuting and this practice is likely to expand further given the positive perceptions and emotional impact of telecommuting and the fact that such practices could turn out to be highly productive. Against this background it is important that practitioners and researchers need to continuously examine how the implementation of a telecommuting programme affects all parties, not only the telecommuters. This is precisely what the Unisa telecommuting baseline study has achieved and it is anticipated that these findings will better inform open distance higher education institutions of the factors and issues that interplay in the dynamics of the telecommuting arrangement and how to increase the effectiveness of their telecommuting programme to the benefit of all stakeholder groups.

Alvi, S., & McIntyre, D. (1993). The open collar worker. Canadian Business Review, 20(1), 21-24.

Apgar, M. V. (1998). The alternative workplace: Changing where and how people work. Harvard Business Review, May-June, 121-136.

Baig, E. C. (1995). Welcome to the officeless office: Telecommuting may finally be out of the experimental stage. Business Week, June 26, 104-106.

Bailey, D. E., & Kurland, N. B. (2002). A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 383-400.

Barthel, M. (1995). Telecommuting finding a home at banks. American Banker, 16, February 1.

Baruch, Y., & Nicholson, N. (1997). Home, sweet work: Requirements for effective home working. Journal of General Management, 23(2), 15-30.

Brown, J. M. C. (2010). Telecommuting: The affects and effects on non-telecommuters. Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Falls Church, Virginia. (18 March.)

Caudron, S. (1992). Working at home pays off. Personnel Journal, November, 40-49.

Chapman, A. J., Sheehy, N. P., Heywood, S., Dooley, B., & Collins, S. C. (1995). The organizational implications of teleworking. In C. L. Cooper, & I.T. Robertson, (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 229-248). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Christensen, K. E. (1992). Managing invisible employees: How to meet the telecommuting. Employment Relations Today, Summer, 133-143.

Côté-O’Hara, J. (1993). Sending them home to work: Telecommuting. Business Quarterly, 57(3), 104-109.

Cooper, C., & Kurland, N. B. (2002). Telecommuting, professional isolation and employee development in public and private organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 511-532.

Cross, T. B., & Raizman, M. (1986). Telecommuting: The future technology of work. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Davenport, T. H., & Pearlson, K. (1998). Two cheers for the virtual office. Sloan Management Review, 39(4), 51-65.

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2012). Green paper for post-school education and training. Pretoria. (January.)

DeSanctis, G. (1984). Attitudes towards telecommuting: Implications for work at home programs. Information and Management, 7(3), 133-139.

DHET, see Department of Higher Education and Training.

Di Martino, V., & Wirth, L. (1990). Le télétravail, un nouveau mode de travail et de vie. Revue Internationale du Travail, 129(5), 585-611.

Doswell, A. (1992). Home alone? - Teleworking. Management Services, October, 18-21.

Duxbury, L., & Higgins, C. (1995). Rapport sommaire sur le projet-pilote de télétravail de Statistiques Canada. Canada: Statistics Canada. (January, Document # 75F0008XPF.)

Duxbury, L., & Neufield, D. (1999). An empirical evaluation of the impacts of telecommuting on intra-organizational communication. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 16(1), 1-28.

Eldib, O. E., & Minoli, D. (1995). Telecommuting. Boston, MA: Artech House.

Ellison, J. K. (2012). Ergonomics for telecommuters & other remote workers. Des Plaines, United States: American Society of Safety Engineers.

Federal Communications Commission. (2003). Report on supervisor/manager telecommuting survey. Audit Report no 03-AUD-09-17. (25 November.)

Fitzer, M. M. (1997). Managing from afar: Performance and rewards in a telecommuting environment. Compensation and Benefits Review, 29(1), January-February, 65-73.

Fritz, M. B. W., Narasimhan, S., & Rhee, H. K. (1998). Communication and coordination in the virtual office. Journal of Management Information Systems, 14(4), 7-28.

Froggatt, C. C. (1998). Telework: Whose choice is it anyway? Facilities Design and Management, Spring, 18-21.

Golden, T. (2007). Co-workers who telework and the impact on those in the office: Understanding the implications of virtual work for co-worker satisfaction and turnover intentions. Human Relations, 60(11), 1641-1667.

Gordon, G. E., & Kelly, M. M. (1986). Telecommuting: How to make it work for you and your company. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall.

Gordon, G. (2006). HP downshifts telecommuting. Retrieved from http://www.workforce.com/section/00/article/24/42/47.html

Gray, M., Hodson, N., & Gordon, G. (1993). Teleworking explained. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley and Sons.

Greengard, S. (1995). All the comforts of home. Personnel Journal, 74, 104-108.

Guimaraes, T., & Dallow, P. (1999). Empirically testing the benefits, problems, and success factors for telecommuting programs. European Journal of Information Systems, 8, 40-54.

Hamilton, C. A. (1987). Telecommuting. Personnel Journal, April, 91-101.

Harrington, S. J., & Ruppel, C. P. (1999). Telecommuting: A test of trust, competing values, and relative advantage. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 42(4), 223-239.

Huws, U. (1984). The new homeworkers: New technology and the changing location of white-collar work. London, UK: Low Pay Unit.

Igbaria, M. (1998). The virtual workplace (electronic book). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing.

Ipsos. (2011). Telecommuting: How often do you currently telecommute with your work? Global@dvisory, (G@26). November.

Johnson, M. (1997). Teleworking…in brief. Oxford, UK: Butterwoth-Heinemann.

Katz, A. I. (1987). The management, control, and evaluation of a telecommuting project: A case study. Information and Management, 13, 179-1190.

Kinsman, F. (1987). The telecommuters. Chichester, England: John Wiley and Sons.

Kirkley, J. (1994). Business week’s conference on the virtual office. Business Week, September 5, 63-66.

Kline, P. (1999). The handbook of psychological testing (2nd ed). London: Routledge.

Korzeniowski, P. (1997). The telecommuting dilemma. Business Communications Review, April, 29-32.

Kraut, R. E. (1987). Predicting the use of technology: The case of telework. In R. E. Kraut (Ed.), Technology and the transformation of white-collar work (pp.113-133). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kugelmass, J. (1995). A manager’s guide to flexible work arrangements. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Mahfood, P. E. (1992). Home work: How to hire, manage and monitor employees who work at home. Chicago, Ill: Probus Publishing Company.

Martinez, J. G. (2004). The effects of telecommuting on attitudinal and behavioural characteristics of organisational culture. Focus III, 1, 19-34.

McCloskey, D. W., & Igbaria, M. (2003). Does ‘out of sight’ mean ‘out of mind’? An empirical investigation of the career advancement prospects of telecommuters. Information Resources Management Journal, 16(2), 19-35.

McCune, J. C. (1998). Telecommuting revisited. Management Review, February, 10-16.

Mid-America Regional Council. (2013). Common questions about telecommuting. Retrieved from http://www.marc.org/rideshare/telecommutefaq.htm

Ng, C. F. (2006). Academics telecommuting in open and distance education universities: Issues, challenges, and opportunities. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 7(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/300/632.

Nilles, J. M. 1975. Telecommunications and organisational decentralisation. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 23, 1142-1147.

Nilles, J. M. (1994). Making telecommuting happen: A guide for telemarketers and telecommuters. New York: Van Nostrand Reinold.

Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Olson, M. H. (1987a). Telework: Practical experience and future prospects. In R. E. Kraut (Ed.), Technology and the transformation of white-collar work (pp. 135-152). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Olson, M. H. (1987b). An investigation of the impact of remote work environment and supporting technology. New York: New York University. (Working paper, Center of Research on Information Systems.)

Olson, M. H. (1988). Organizational barriers to telecommuting. In W. B. Korte, B. Steinle, & S. Robinson, (Eds.), Telework: Present situation and future development of a new form of work organization (pp. 77-100). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Pinsonneault, A., & Boisvert, M. (1999). The impacts of telecommuting on organizations and individuals: A review of the literature. Retrieved from http://expertise.hec.ca/gresi/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/cahier9909.pdf

Pinsonneault, A., & Boisvert, M. (2001). The impacts of telecommuting on organizations and individuals: A review of the literature. In N. J. Johnson, (Ed.), Telecommuting and virtual offices: Issues and opportunities (pp. 163-185). Hershey, P. A.: Idea Group Publishing.

Potter, E. (2003). Telecommuting: The future of work, corporate culture, and American society. Journal of Labor Research, 23(1), 73-83.

Pratt, J. (1984). Home teleworking: A study of its pioneers. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 25, 1-14.

Psikurich, G. M. (1996). Making telecommuting work. Training and Development, February, 22.

Ramsower, R. M. (1985). Telecommuting: The organizational and behavioral effects of working at home. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press.

Reinsch, N. L. Jr. (1997). Relationship between telecommuting workers and their managers: An exploratory study. The Journal of Business Communications, 34(4), 343-369.

Richter, J., & Meshulam, I. (1993). Telework at home: The home and the organization perspective. Human Systems Management, 12, 193-203.

Ruppel, C. P., & Harrington, S. J. 1995. Telework: Innovation where nobody is getting on the bandwagon. Data Base Advances, 26(2-3), 87-104.

Solomon, N. A., & Templer, A. J. (1993). Development of non-traditional work sites: The challenge of telecommuting. Journal of Management Development, 12(5), 21-32.

TeamViewer®. (2012, April). Telecommuting for earth survey by uSamp. Germany. Retrieved from http://www.gfi.com/blog/survey-americans-stress-benefits-and-demands-of-telecommuting-infographic/

Trembly, A. C. (1998). Telecommuting productively. Beyond Computing, 7(4), 42-44.

Unisa, see University of South Africa.

University of South Africa. (2011). Directive: Professors working from home. Unisa.

University of South Africa. (2013). The leading ODL university. Retrieved from http://www.unisa.ac.za/Default.asp?Cmd=ViewContent&ContentID=17765

Weiss, J. M. (1994). Telecommuting boosts employee output. HR Magazine, 39, 51-53.

Wikipedia. (2013). Telecommuting. (November). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Telecommuting

Wilkes, R. B., Frolick, M. N., & Urwiler, R. (1994). Critical issues in developing successful telework programs. Journal of Systems Management, 45, 30-34.

Xenakis, J. J. (1997). Workers in the world disperse! CFO, 13(10), 79-85.

Yamini, F., Balakrishnan, H., Nguyen, G., & Lopez, X. (1997). Real-time collaborative technologies: Incentives and impediments. (3 April.) Berkley: University of California. Retrieved from http://www-inst.eecs.berkeley.edu/~eecsba1/sp97/reports/eecsba1d/report/

Yick, A. G., Patrick, P., & Costin, A. (2005). Navigating distance and traditional higher education: Online faculty experiences. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 6(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewArticle/235/320

1 Defined by the Department of Higher Education and Training as education that normally takes place in universities and other higher education institutions, both public and private, which offer qualifications on the Higher Education Qualifications Framework (HEQF) (DHET, 2012).