|

|

Joel S. Mtebe and Roope Raisamo

University of Tampere, Finland

The past few years have seen increasingly rapid development and use of open educational resources (OER) in higher education institutions (HEIs) in developing countries. These resources are believed to be able to widen access, reduce the costs, and improve the quality of education. However, there exist several challenges that hinder the adoption and use of these resources. The majority of challenges mentioned in the literature do not have empirically grounded evidence and they assume Sub-Saharan countries face similar challenges. Nonetheless, despite commonalities that exist amongst these countries, there also exists considerable diversity, and they face different challenges. Accordingly, this study investigated the perceived barriers to the use of OER in 11 HEIs in Tanzania. The empirical data was generated through semi-structured interviews with a random sample of 92 instructors as well as a review of important documents. Findings revealed that lack of access to computers and the Internet, low Internet bandwidth, absence of policies, and lack of skills to create and/or use OER are the main barriers to the use of OER in HEIs in Tanzania. Contrary to findings elsewhere in Africa, the study revealed that lack of trust in others’ resources, lack of interest in creating and/or using OER, and lack of time to find suitable materials were not considered to be barriers. These findings provide a new understanding of the barriers to the use of OER in HEIs and should therefore assist those who are involved in OER implementation to find mitigating strategies that will maximize their usage.

Keywords: Open educational resources; eLearning; OER in Tanzania; OER; higher education; Sub-Saharan Africa; Tanzania

Tanzania like many African countries is faced with increased demand for higher education. According to O. Ezekwesili, the World Bank’s VP for Africa, only 6% of Africans participate in higher education compared to a world average of 25.5% (Kokutsi, 2011). In Tanzania, only 1.48% of Tanzanians participate in higher education (Lindow, 2011, p. 13). This percentage of student enrolment is expected to increase due to the recent expansion of secondary education under the Secondary Education Development Program (SEDP) (2004-2007). The SEDP has increased the enrolments in secondary education from 432,599 in 2000 to 1,020,510 in 2006, reaching 34% of the school-going population in 2011 (URT, 2012). Consequently, the demand for higher education has increased massively.

Naturally, higher education institutions (HEIs) have been adopting various information and communication technologies (ICT) in a bid to meet this increased demand for higher education and to improve the quality of education. As of 2011, 80.2% of institutions were using various educational systems mostly learning management systems (LMS) (Munguatosha, Muyinda, & Lubega, 2011). Additionally, several institutions have been installing complex ICT infrastructure, video conferencing facilities, and other related technologies (Lwoga, 2012).

Despite these initiatives, institutions will not be able to widen access to and improve the quality of education without taking into consideration the quality of learning resources. This is because students rely on learning resources as their major source of information during the learning process (Keats, 2003). However, most institutions have continued with print-dependent educational practices where learning resources are in the form of paper textbooks and course handouts. Most of these resources are expensive, lack contextual relevance, and are difficult to share with a wider group of students (Keats, 2003; Lwoga, 2012). As the cost of textbooks and other printed resources from commercial companies continues to rise, institutions tend to use outdated books, and old or poorly designed learning resources (Keats, 2003; Ngugi, 2011).

The recent emergence of open educational resources (OER) can immensely contribute towards providing quality learning resources in HEIs in Tanzania. These are freely and openly available digitized resources that can be adapted, modified, and re-used for teaching, learning, and research (OECD, 2007). To date, thousands of resources across all disciplines have been developed and shared in the public domain through the support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Commonwealth of Learning (COL), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and other international agencies. They include full courses, course modules, video of lectures, homework assignments, simulations, and electronic textbooks.

As of 2007, over 3,000 learning resources from over 300 universities were available (OECD, 2007). These include 1,900 courses from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), 2,500 courses from over 200 universities under the OCW Consortium, and more than 1,500 courses under the Japanese OCW Consortium (Butcher, 2010). Other resources include 750 from China Open Resources for Education and more than 22,500 resources from Multimedia Educational Resources for Learning and Teaching Online (MERLOT) (Yuan, Mac, & Kraan, 2008).

Moreover, there are African-based initiatives that have shared thousands of resources developed by African academics. For instance, OER Africa in partnership with the University of Michigan has shared more than 150 resources related to health education (Lesko, 2013). Similarly, COL and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation have developed and shared 20 self-study selected subjects at the secondary-school level (Wright & Reju, 2012). Other examples of OER African based initiatives include Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa (TESSA) and University of Cape Town (UCT) Open Content.

The appropriate use of OER in higher education can widen access, reduce the costs, and improve the quality of education in Sub-Saharan countries. The quality of education is improved when instructors and learners can easily access resources that they were unable to access due to cost and/or copyright laws (Wright & Reju, 2012). Wright and Reju added that OER could benefit instructors who do not have teaching experience and knowledge of the subject matter that they are teaching. Additionally, instructors can use these resources to improve the quality of existing courses or develop new courses by adapting existing courses (Butcher, 2011).

The OER can also complement existing blended learning courses offered by several institutions in Tanzania. By doing so, institutions will be able to widen access to education and reduce social inequalities (Butcher, 2011; Freitas, 2012). Furthermore, HEIs can attract more students, increase institutional reputation, and attract research funding and new partnerships through participating in OER initiatives (Butcher, 2011; Hylén, 2006). For example, 35% of new students who applied for various courses at MIT were influenced by free MIT courses they accessed previously (Caswell, Henson, Jensen, & Wiley, 2008; MIT, 2006).

Despite the potential benefits offered by OER, the use of these resources in many HEIs in Sub-Saharan countries is very low (Freitas, 2012; Hoosen, 2012; Unwin et al., 2010). MIT OCW statistics show that only 2% of users have come from Sub-Saharan countries since 2004 (MIT, 2013). Likewise, in the past two years, almost 2 million users who accessed OER Africa resources were from South America, North America, Europe, and India (Richards, 2013).

According to Hoosen (2012), the majority of institutions in Tanzania are not active in OER initiatives. For example, in a study conducted by Samzugi and Mwinyimbegu (2013) at the Open University of Tanzania (OUT), only 21.8% of 150 respondents indicated that they had heard about OER. Likewise, none of the departments reported use of MIT resources despite the fact that the University of Dar es Salaam signed an agreement with MIT a few years ago. Clearly, the perceived benefits of OER cannot be realized if academics in higher education do not use them.

Therefore, it is important to investigate underlying inhibiting factors that prevent instructors from using OER in order to develop strategies that will maximize their usage. So far, however, there has been little research around OER use in Africa in general (Percy & Belle, 2012). The majority of studies in the literature have focused on development and publication of OER repositories as well as on the integration of policies in various institutions (Andrad et al., 2011). A small number of studies have discussed barriers to the use of OER without empirically grounded evidence and they assume all Sub-Saharan countries are facing similar challenges (Hatakka, 2009; Hodgkinson-Williams, 2010).

Recently, Mtebe and Raisamo (2014) conducted a study to identify challenges that hinder instructors to adopt and use OER in higher education in Tanzania. They found that performance expectancy, facilitating conditions, and social influence did not have a statistically significant effect on instructors’ intention to adopt and use OER. Only effort expectancy had a significant positive effect. The research was based on quantitative data obtained from 104 instructors in 5 HEIs and they applied the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model.

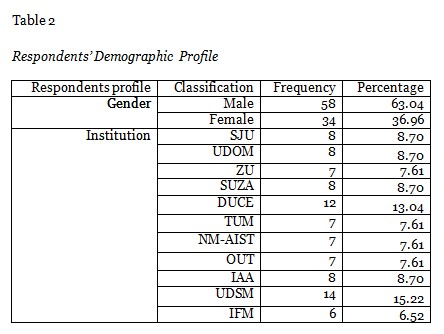

This study provides further understanding of the perceived barriers to the use of OER based on qualitative data from 11 HEIs in Tanzania. The surveyed institutions were: St John University (SJU), University of Dodoma (UDOM), Zanzibar University (ZU), State University of Zanzibar (SUZA), Dar es Salaam University College of Education (DUCE), and Tumaini University Makumira (TUM). Other institutions were: Nelson Mandela African Institution of Science and Technology (NM-AIST), Open University of Tanzania (OUT), The Institute of Accountancy Arusha (IAA), University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM), and the Institute of Finance Management (IFM).

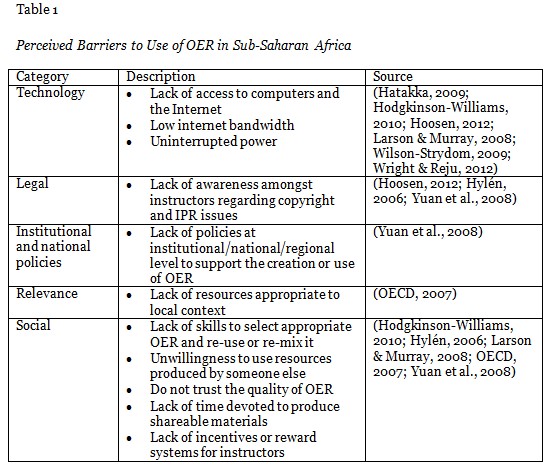

A considerable amount of literature has been published to explain factors that hinder the use of OER in Sub-Saharan countries. Generally, studies have consistently described the shortage of computers and Internet and low Internet bandwidth as the main contextual barriers to the use of OER in Africa (Hatakka, 2009; Hodgkinson-Williams, 2010; Hoosen, 2012; Larson & Murray, 2008; Wilson-Strydom, 2009). Other main barriers cited include the lack of understanding regarding copyright and intellectual property rights (IPR) issues (Hoosen, 2012; Hylén, 2006; Yuan et al., 2008), and lack of policies to encourage creation and sharing of OER (Yuan et al., 2008).

Additionally, some studies have focused on social factors (Hodgkinson-Williams, 2010; Hylén, 2006; Larson & Murray, 2008; OECD, 2007; Yuan et al., 2008). These factors include lack of skills to find and use OER, lack of time to find and/or prepare OER, and unawareness of OER existence. Other social factors include the lack of trust on the quality of OER and inability to find appropriate OER relevant to users in Africa. Table 1 summarizes some of these perceived barriers to the use of OER in Africa.

Most barriers to the use of OER cited in several studies (as shown in Table 1) are not based on empirically grounded evidence (Hatakka, 2009; Hodgkinson-Williams, 2010). A small number of studies with empirical evidence shows that these challenges are not uniform in all Sub-Saharan countries. For example, in a study conducted in Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa with 19 participants from TESSA found that low technology levels was not a barrier to the use of OER (Ngimwaa & Wilsona, 2012). The real challenges were socio-economic, cultural, institutional, and national issues.

Another study conducted amongst 24 respondents from 24 countries in Africa found connectivity and IPR issues were the main obstacles to the use of OER in Africa (Hoosen, 2012). These findings were somewhat consistent with those conducted by Percy and Belle (2012) with 68 respondents across Africa. They found technology and locating relevant OER were the main barriers. Similarly, in a study conducted with 200 respondents at OUT, Samzugi and Mwinyimbegu (2013) found that the barriers were a lack of skills to locate relevant resources and unawareness of the existence of OER.

The most recent study to identify challenges to the use of OER was conducted by Lesko (2013) in 17 HEIs in South Africa using a sample of 120 respondents. The author found that the lack of knowledge related to OER usage, lack of awareness of copyright and IPR issues, infrastructural challenges, and lack of knowledge about the existence of OER were the main barriers. The empirical findings from these few studies indicate that users from different Sub-Saharan countries face different challenges to the use of OER. This claim is supported by Bateman (2008) who pointed out that, despite commonalities that exist amongst these countries, there also exists considerable diversity, and they face different challenges.

Therefore, there is a need to empirically investigate factors that hinder instructors from using OER in HEIs in Tanzania. This will help those who are involved in OER implementation to find relevant corrective measures to promote and maximize their level of usage. This study comes at a time when HEIs have been adopting various ICT to complement existing open and distance learning (ODL) courses to widen access to needy students. The use of OER will definitely help institutions to provide quality learning resources to support these initiatives.

The study used semi-structured interviews and documentary reviews as data collection methods. The interview process involved a series of open–ended questions to investigate how instructors were using Internet affordances to prepare learning resources, as well as to elicit instructors’ views on the use of OER in teaching. According to Bryman (2008), semi-structured interviews enable the respondents to project their own ways of defining the world, permit a sequence of discussions, and enable the participants to raise issues that might not have been included in a pre-devised schedule.

The surveyed HEIs were selected on a convenience basis due to time and budgetary constraints. However, there was an adequate distribution of institutions across the country. Once institutions were identified, instructors were selected at random from various schools and faculties within a given institution and the selection was based on willingness to participate. Out of 163 instructors who were contacted, 98 instructors agreed to be interviewed. Due to unavailability of some instructors, we managed to interview 92 in total. During the interview process, some important institutional documents were reviewed in order to investigate the availability of enabling conditions that support the use of OER: bandwidth, policies, and use of eLearning systems.

Finally, from their personal experience instructors were asked to evaluate the relevance of 10 selected barriers to the use of OER in HEIs in Tanzania. The barriers included: access to computers and the Internet, Internet bandwidth, policies at institutional level to support the creation and/or use of OER, lack of time to find suitable materials, and lack of skills to create and/or use OER. Other barriers that were selected included concerns over copyright and IPR issues, difficulties in finding suitable and relevant OER, quality of OER, lack of trust in others’ resources, and lack of interest to create and/or use OER.

Instructors were asked to rate these barriers using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. These factors were extracted from the literature reviewed on factors that hinder the use of OER in HEIs in Africa. The study adapted factors that were relevant to the context of higher education in Tanzania. The selection of a face-to-face quantitative data collection method was based on the fact that the response rate for online data collection is normally very low and we had limited time.The research was undertaken between October 2013 and January 2014.

Mostrespondents were male,63.04%;36.96% were female. There was almost an equal distribution of respondents across institutions with the exception of DUCE and UDSM which had more respondents. There were 14 (15.22%) respondents from UDSM and 12 (13.04%) respondents from DUCE. The number of respondents per institution is shown in Table 2.

The study assessed how instructors use Internet services to prepare and share learning resources.

The study found that the majority of instructors use the Internet to search for course notes with 55% of respondents using it several times per week, and 33% of respondents using it every day. Nonetheless, 33% of respondents did not include web-based photos, audio, or videos in their courses, while 35% of respondents indicated that they did so several times per week.

Only a small number of respondents (18%) indicated that they never used social networks while 8% of respondents used it once per month. Clearly, the majority of instructors used social media networks frequently for social activities with 37% of respondents using them daily, while 27% of respondents used them several times per week.

More than two-thirds of respondents (73%) were aware of the OER movement while 27% of instructors were not aware of it. However, the majority of participants had rarely or never used OER to enhance their courses.

The study found that 79% of respondents had never included OER in their courses, while 21% of respondents used OER at some stage during their preparation of learning resources. Those instructors who used OER during course preparation were asked to mention at least one OER repository they used. Some of the OER repositories mentioned are: Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), MIT, Khan Academy, OpenCourseWare Consortium, and Google scholar. They were further asked to explain why they included OER in their courses. Here are some of their responses.

Yes. It helps me to enrich my teaching materials by reading materials from different authors and publications.

I have used some of them in notes and test questions i.e. using the questions provided in the material to give to my students because they are ready made and have answers which make it easy for me to mark.

Those who said no were asked to explain why they do not use OER in preparing their teaching resources. Some of their comments were:

No, due to lack of proper information on how to search relevant OER.

Yes! OER usage is good but most of us are not well educated on this issue and therefore I suggest those who are literate on this aspect to organize seminars and/trainings for lecturers to attend and be equipped with knowledge and skills on the use of OER.

OER is still a new jargon in HEIs in Tanzania. I believe instructors do not use it if for any other reason is because they simply don’t know if they exist, and how to use them. I believe awareness training will build their capacity and they will use them, even with low bandwidth challenge.

The study found that the majority of instructors (83%) was not aware of Creative Commons licenses. However, 17% of instructors indicated that they had heard about these licenses before.

Through document review, the study investigated the availability of enabling conditions for the smooth adoption and use of OER in higher education. For each surveyed institution, the following factors were assessed: Internet speed, availability of ICT policies and/or eLearning policies, and use of eLearning systems for teaching and learning.

The study found that the Internet is generally good in most of the surveyed institutions with the exception of SJU, IAA, and TUM. UDSM and DUCE had the highest bandwidth (155mbps) because they were connected to the SEACOM marine cable. Table 3 shows Internet bandwidth in the surveyed institutions.

The study found that all of the surveyed institutions had ICT policies in place. The results showed that 54.5% of institutions had both ICT policy and eLearning policy in place, while 45.5% of institutions did not have eLearning policies. Nonetheless, interviewees pointed out that most of these policies were not operational. For example, one respondent from one institution said: “…ICT policy and eLearning policy exist only as documents (are in documentation) and they are not implemented”

It was revealed that almost half of the surveyed institutions (54.5%) were using Moodle LMS while 45.5% of them were not using any LMS. With the exception of UDSM, SJU, and SUZA, the number of active users in the systems was very low. For instance, there were 103 users at UDOM, 81 users at OUT, and 49 users at IFM.

Sixty-eight percent of respondents indicated that lack of access to computers and the Internet was a barrier to the use of OER. Further evidence was obtained from interviews as shown below:

…lack of facilities and equipment like computers, intranet and reliable Internet connections

…not enough facilities (computer and Internet connections) to allow them use OER

…sometimes accessibility and availability of Internet connection is problematic to many HEIs

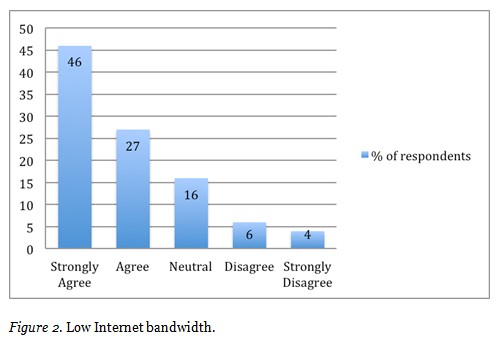

The study found 73% of respondents rated low Internet bandwidth as a barrier to the use of OER. Fifteen percent of respondents were neutral while a small number of respondents (10%) indicated that low Internet bandwidth was not an inhibiting factor (See Figure 2).

In addition, the findings were supported by some comments extracted from interviews as shown below:

One of the drawbacks is reliable Internet connection and easy accessibility

… unreliable power and slow Internet connection

… but also unstable Internet connection problem contributes in preventing lecturers from using OER.

…may be due to poor Internet connection speed, and regular cut of electricity that interfere much their timetables

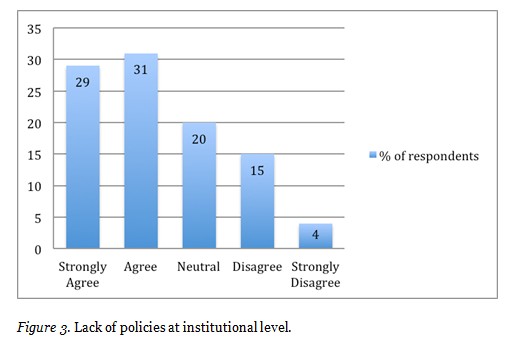

A small number of instructors (19%) said the lack of policies at institutional level was not a hindrance factor to the use of OER. However, the majority of instructors (60%) rated lack of relevant policies as a hindrance factor (Figure 3).

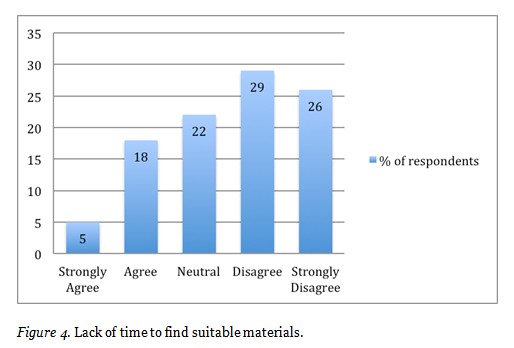

The study revealed that the majority of respondents (55%) felt that the lack of time to find suitable materials was not a hindrance factor. Twenty-two percent of respondents who were undecided while 23% of respondents indicated lack of time to find suitable materials was a barrier. Figure 4 indicates the distribution of responses on this factor.

We were interested to find more on why lack of time to find learning resources via OER was a barrier. Here were some of the comments from respondents:

…the amount of time spent searching for relevant material on the Internet is a barrier, you need to spend like 4 hrs per day just to search resources and remember we have other activities as well to do.

...the truth is, for many experienced Lecturers, there is very little time to prepare teaching notes, or even lessons because they have been teaching the same thing for a long time and they feel they know everything and that their lessons are complete and are of international standard

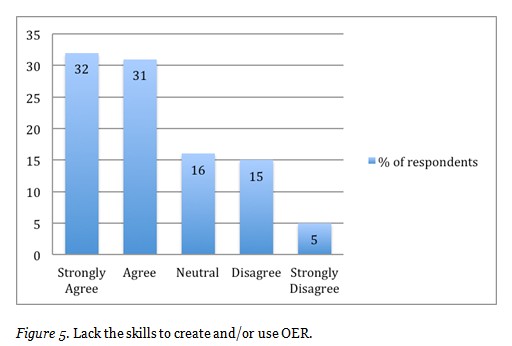

The study found that 63% of respondents said the lack of skills to create and/or use OER was a barrier to the use of OER. Only a small number of respondents (20%) indicated that lack of skills to create and/or use OER was not a barrier. However, 16% of instructors were neutral (Figure 5).

From the interviews, many instructors described lack of skills to find OER as a barrier. Here are some of the comments:

…most of lecturers are unaware of OERs and even if some have glimpse of it lack knowledge on how to access them

…lack of know-how and equipment, also steady and fast Internet connection. So they prefer to use other means, but once the former exist I am sure many will use OER

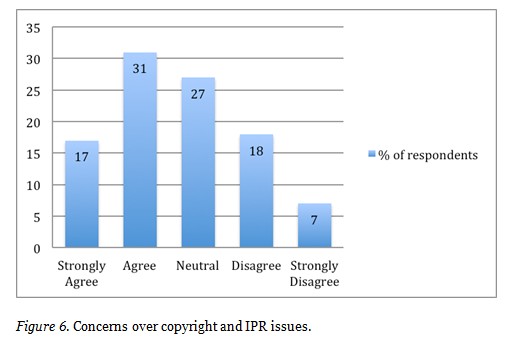

Nearly half of respondents (48%) pointed out that concerns over copyright and IPR issues was a barrier to the use of OER. Nevertheless, 25% of respondents indicated that a concern about copyright and IPR issues was not a hindrance factor. Twenty-seven percent of respondents were undecided (See Figure 6).

The comments from interviews showed that respondents were worried about sharing their resources due to unawareness of copyright issues. Here are some of the comments:

…afraid of plagiarism. Some lecturers do not understand the concept very well, most of what they write is copied from the Internet or books, therefore there is a fear that if they let the material be free, they can be sued for plagiarism

…instructors lack knowledge on the existence of OER and how to use OER but also fear to share their materials with fear of copyright issues.

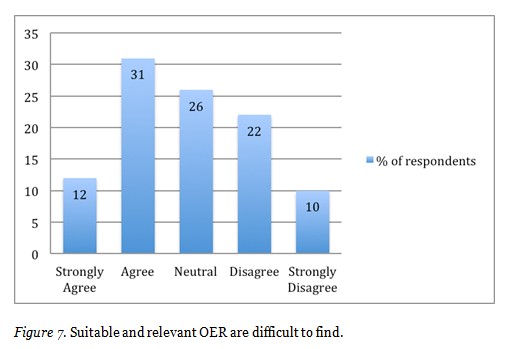

The study found that 43% said difficulties in finding relevant OER was a barrier.. However, 26% of respondents were neutral on whether the challenge of finding relevant OER was a hindrance factor or not (See Figure 7).

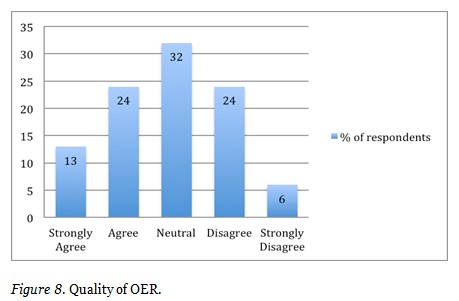

Instructors were almost equally divided on whether quality of OER was a barrier to the use of OER. Thirty-five percent of respondents felt that quality of OER was a barrier, 32% of respondents were neutral, and 30% of respondents rated it as a barrier. The distribution of responses is shown in Figure 8.

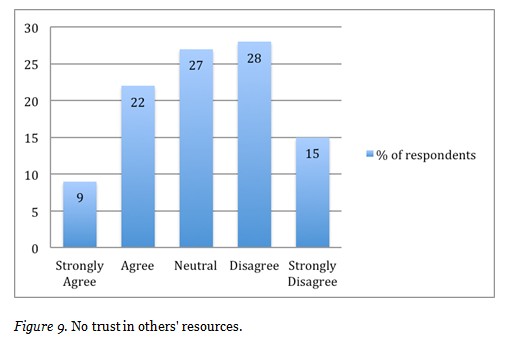

The study revealed that many of the respondents (43%) said the lack of trust in others’ resources was not a barrier to the use OER. Nonetheless, nearly one-third (27%) of respondents were undecided, while 31% of respondents suggested that no trust in others’ resources was a barrier (Figure 9).

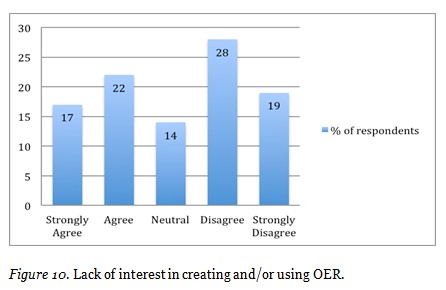

The study revealed that approximately half of the respondents (45%) said the lack of interest to create and/or use OER was not a barrier to the use of OER. On the other hand, 39% of respondents rated it as a barrier, while a minority of respondents (14%) was undecided (See Figure 10).

This study aimed to investigate the barriers to the use of OER in HEIs in Tanzania. The main findings are that lack of access to computers and the Internet, low Internet bandwidth, lack of policies, and lack of skills to create and/or use OER were considered as important inhibiting factors to use OER in HEIs in Tanzania.

The findings of the current study are consistent with those of Lwoga (2012), Samzugi and Mwinyimbegu (2013), and Tedre, Ngumbuke, and Kemppainen (2010) who found that low Internet bandwidth was a major obstacle to the use of various eLearning solutions in higher education in Tanzania. This study found that in the majority of surveyed institutions the Internet speed ranged from 7mbps to 20mbps with the exception of UDSM and DUCE. UDSM and DUCE had Internet speed of 155mbps as they are already connected to the SEACOM marine fibre cable.

Similarly, the cost of Internet connectivity in Tanzania is still high (Lwoga, 2012; Tedre et al., 2010). For example, one university surveyed by Lwoga (2012) was paying 104 million TShs per year, while another institution surveyed by Tedre et al. (2010) was paying 4 million TShs (2140€ = 3100$) per month for a dedicated 704kb/128kb satellite connection for 300 computers. It seems that limited Internet and its cost are barriers to the use of OER in many countries in Africa as similar findings were found in Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa (Ngimwaa & Wilsona, 2012). According to Wright and Reju (2012), OER may not be open and free for those who do not have access to computers and the Internet. Therefore, the use of OER in higher education will depend on increased access to computers and reasonably priced Internet services.

The study also found that lack of policies at an institutional level was a major barrier to the use of OER in the surveyed institutions. This finding was consistent with the fact that nearly half of surveyed institutions (45.5%) did not have eLearning policies in place. Even in institutions that had eLearning policies in place, the majority of them were not implemented. In some institutions, these policies existed but were out-dated and were developed when OER was at an early stage of implementation. For example, the UDSM ICT policy was developed in 2006, while that of OUT was developed in 2009 (Mtebe & Raisamo, 2014). Therefore, such policies do not clarify issues that hinder the adoption of OER such as IPR and quality assurance (Bossu, Bull, & Brown, 2012). This could be why 83% of instructors indicated that they were not aware of Creative Commons licenses.

Another main barrier to the use of OER that emerged from this study was lack of the skills to create and/or use OER. Nearly two thirds of respondents (63%) rated this as a hindrance factor. This finding corroborates a study conducted by Samzugi and Mwinyimbegu (2013) to investigate the accessibility of OER at OUT. They revealed that users depended on librarian assistance to find relevant OER due to lack of skills. Unless instructors are equipped with necessary skills to be able to create and/or use these resources, the use of OER in HEIs in Tanzania will be very difficult.

The most interesting finding from this study was that lack of trust in others’ resources, lack of interest in creating and/or using OER, and lack of time to find suitable materials were not considered to be the main barriers to the use of OER in the surveyed institutions. This finding was consistent with the fact that many instructors used the Internet to search for course notes to enhance their courses. This implies that instructors do trust resources from the Internet and they have the interest and time to find them. Nonetheless, they are not aware of reputable OER repositories where they could find quality resources. Therefore, in order to maximise the use of OER, there is an urgent need to raise awareness at all levels involving institutions and government entities of the value of OER in enhancing education (Ngimwaa & Wilsona, 2012).

It is somewhat surprising that respondents were almost equally divided on two factors: lack of quality of OER and difficulties in finding suitable and relevant OER. Nearly one-third of interviewed instructors suggested that these two factors were barriers to the use of OER, while another one third indicated they were not. Similarly, almost one-third of instructors were undecided. This might be because the majority of instructors tend to search resources from unreliable sites due to unawareness of OER repositories. It seems, therefore, instructors compare the quality of the resources they search from the Internet with that of OER.

The adoption and use of ICT to improve the quality of education and to increase students’ enrolments through blended distance learning in Tanzania is becoming common. Many HEIs are spending thousands of dollars to procure and maintain various ICT in their premises. With these efforts in place, the use of OER to complement these initiatives cannot be ignored. However, in order to benefit from these resources institutions have to find ways to overcome challenges revealed in this study. Moreover, institutions have to

The authors appreciatively acknowledge the financial support from South African Institute for Distance Education (Saide), University of Dar es Salaam and the support from University of Tampere for preparing this article. The authors would also like to thank instructors from 11 institutions in Tanzania who willingly agreed to participate in the study.

Andrad, A., Ehlers, U.-D., Caine, A., Carneiro, R., Conole, G., Kairamo, A.-K., … Holmberg, C. (2011). Beyond OER: Shifting focus to open educational practices. Retrieved from http://www.oerasia.org/OERResources/8.pdf

Bateman, P. (2008). Revisiting the challenges for higher education in Sub-Saharan Africa : The role of the open educational resources movement OER Africa (pp. 1–66). Nairobi, Kenya.

Bossu, C., Bull, D., & Brown, M. (2012). Opening up down under : The role of open educational resources in promoting social inclusion in Australia. Distance Education, 33(2), 151–164.

Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butcher, N. (2010). OER dossier : Open educational resources and higher education. South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/OER_Open_Educational_Resources_and_Higher_Education.pdf

Butcher, N. (2011). A basic guide to open educational resources (OER) (pp. 1–134). COL: Vancouver & Paris. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=357

Caswell, T., Henson, S., Jensen, M., & Wiley, D. (2008). Open educational resources: Enabling universal education. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(1). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/469/1001

Freitas, D. (2012). Fostering social inclusion through open educational resources (OER). Distance Education, 33(2), 131–134.

Hatakka, M. (2009). Build it and they will come?–Inhibiting factors for reuse of open content in developing countries. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 37(5), 1–16.

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. (2010). Benefits and challenges of OER for higher education institutions. Retrieved from http://www.col.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/OER_BenefitsChallenges_presentation.pdf

Hoosen, S. (2012). Survey on governments’ open educational resources (OER) policies (pp. 1–40). Retrieved from http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=408

Hylén, J. (2006). Open educational resources : Opportunities and challenges. In Open Education. Retrieved from http://library.oum.edu.my/oumlib/sites/default/files/file_attachments/odl-resources/386010/oer-opportunities.pdf

Keats, D. (2003). Collaborative development of open content: A process model to unlock the potential for African universities. First Monday, 8(2). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/rt/printerFriendly/1031/952

Kokutsi, F. (2011). AFRICA: Expand university access, World Bank urges. University World News, Africa Edition Issue 198. Retrieved from http://www.universityworldnews.com

Larson, R. C., & Murray, M. E. (2008). Open educational resources for blended learning In high schools: Overcoming impediments In developing countries. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(1), 2–19.

Lesko, I. (2013). The use and production of OER & OCW in teaching in South African higher education institutions. Open Praxis, 5(2), 103–121.

Lindow, M. (2011). Weaving success: Voices of change in African higher education (p. 239). NewYork, NY 10022: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data.

Lwoga, E. (2012). Making learning and Web 2.0 technologies work for higher learning institutions in Africa. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 29(2), 90–107. doi:10.1108/10650741211212359

MIT. (2006). 2005 program evaluation findings report (pp. 1–138).

MIT. (2013). Site statistics. Retrieved April 08, 2013, from http://ocw.mit.edu/about/site-statistics/

Mtebe, J. S., & Raisamo, R. (2014). Challenges and instructors’ intention to adopt and use open educational resources in higher education in Tanzania. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 15(1), 250–271.

Munguatosha, G. M., Muyinda, P. B., & Lubega, J. T. (2011). A social networked learning adoption model for higher education institutions in developing countries. On the Horizon, 19(4), 307–320. doi:10.1108/10748121111179439

Ngimwaa, P., & Wilsona, T. (2012). An empirical investigation of the emergent issues around OER adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa. Learning, Media and Technology, 37(4), 398–413. doi:10.1080/17439884.2012.685076

Ngugi, C. N. (2011). OER in Africa’s higher education institutions. Distance Education, 32(2), 277–287. doi:10.1080/01587919.2011.584853

OECD. (2007). Giving knowledge for free: The emergence of open educational resources. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/35/7/38654317.pdf

Percy, T., & Belle, J. Van. (2012). Exploring the barriers and enablers to the use of open educational resources by university academics in Africa. In Open source systems: Long-term sustainability (pp. 112–128). Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-33442-9_8

Richards, G. (2013). Tracking the usage of our OER to improve their quality and impact. African Health OER Network Newsletter, 4(7). Retrieved from http://www.oerafrica.org/FTPFolder/Website Materials/Health/Newsletters/2013/August-2013-edition.html#7

Samzugi, A. S., & Mwinyimbegu, C. M. (2013). Accessibility of open educational resources for distance education learners: The case of The Open University of Tanzania. Huria Journal of OUT, 14(76-88).

Tedre, M., Ngumbuke, F., & Kemppainen, J. (2010). Infrastructure, human capacity, and high hopes : A decade of development of e-Learning in a Tanzanian HEI. Redefining the Digital Divide in Higher Education, 7(1).

Unwin, T., Kleessen, B., Hollow, D., Williams, J., Oloo, L. M., Alwala, J., … Muianga, X. (2010). Digital learning management systems in Africa: Myths and realities. Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 25(1), 5–23. doi:10.1080/02680510903482033

URT. (2012). Primary Education Development Programme Phase III ( 2012-2016 ). Retrieved from http://www.ed-dpg.or.tz/pdf/PE/Primary Education Development Plan-PEDP I_2000-06.pdf

Wilson-Strydom, M. (2009). The potential of open educational resources OER Africa (pp. 1–32). Retrieved from http://www.oerafrica.org/understandingoer/UnderstandingOER/ResourceDetails/tabid/1424/mctl/Details/id/36389/Default.aspx

Wright, C. R., & Reju, S. A. (2012). Developing and deploying OERs in sub-Saharan Africa : Building on the present potential of OERs in sub-Saharan Africa. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1185/2161

Yuan, L., Mac, S., & Kraan, W. (2008). Open educational resources – opportunities and challenges for higher education (pp. 1–34). Retrieved from http://wiki.cetis.ac.uk/images/0/0b/OER_Briefing_Paper.pdf