|

|

Deepak Prasad and Tsuyoshi Usagawa

Kumamoto University, Japan

Textbook prices have soared over the years, with several studies revealing many university students are finding it difficult to afford textbooks. Fortunately, two innovations – open educational resources (OER) and open textbooks – hold the potential to increase textbook affordability. Experts, though, have stated the obvious: that students can save money through open textbooks only if teachers are willing to develop and use them. Considering both the high price of textbooks and the benefits offered by OER and open textbooks, the aim of this study was to assess the University of the South Pacific (USP) teachers’ willingness towards development of custom-built OER derived open textbooks for their courses with a focus on providing a foundation for strategies to promote open textbook development at USP. This paper reports the findings of an online survey of 39 USP teachers. The results show that 17 teachers were willing to develop OER derived custom-built open textbooks for their courses. Besides this, there are findings relating to six important areas: teachers’ motivation to develop open textbooks; the frequency of more than one prescribed textbook per course; teachers’ awareness of the costs of the prescribed textbooks; the average cost of prescribed textbooks in a course; teachers’ awareness and utilization of OER and open textbooks; and teachers’ perceived barriers to using OER and types of challenges they encounter while using OER. These findings have been discussed in relation to research studies on OER and open textbooks.

Keywords: Open educational resources; open textbooks; willingness; awareness; barriers; motivators; University of the South Pacific

Textbook prices have clearly spiralled upward in recent years; between 1978 and 2012 textbook costs in the United States of America have risen an alarming 812% (Perry, 2012). Hallam (2012) pointed out that the textbook industry thrives on the notion of ‘prescribed textbooks,’ with more students purchasing textbooks when told to do so by their teacher. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom, 83% of students purchased textbooks when prescribed by the teacher, compared with 30% who purchased textbooks simply due to recommendation (Carpenter, Bullock, & Potter, 2006). Sadly, it is not uncommon to see teachers prescribe multiple textbooks when they cannot find a single textbook that meets the learning objectives of their course (Wiley, Green, & Soares, 2012).

Several studies have revealed the difficulty university students face in affording textbooks. In a 2011 survey of 1,905 undergraduate students, 70% of students reported not purchasing at least one prescribed textbook due to cost, despite 78% believing they would do worse in the course without their own copy of the prescribed text (Allen, 2011). Similarly, according to a 2013 survey of 2,039 students from more than 150 different university campuses, 65% of students indicated they had decided against buying a textbook because it was too expensive, 48% said the cost of textbooks had an impact on how many or which classes they took, and 94% of the students who had avoided buying a prescribed textbook said they were concerned that doing so would negatively affect their grade in that course (Senack, 2014). These surveys indicate that when students do not have their own copy of the prescribed textbooks, they lag behind, compromise their learning outcomes, and increase their chances of failing their course (Acker, 2011; Allen, 2011; Graydon, Urbach-Buholz, & Kohen, 2011; Morris-Babb & Henderson, 2012; Senack, 2014). The above discussion illustrates that the high cost of textbooks has a cumulative adverse impact on higher education that requires a solution.

Fortunately, an innovation known as open textbooks holds the potential to increase textbook affordability (Hilton & Wiley, 2011; Okamoto, 2013). Essentially, “Open textbooks are similar to traditional textbooks in terms of content; however, they are generally available for free in digital format, along with low-cost print copies” (Hilton, Gaudet, Clark, Robinson, & Wiley, 2013, p. 38). Several open textbooks initiatives have emerged lately, promising to address the problem of textbook affordability for students. In a survey of open textbook adoption in three high school science courses, Wiley, Hilton, Ellington, and Hall (2012) report that open textbooks cost over 50% less than traditional textbooks without loss of quality of learning outcomes as measured by standardized tests. In the area of higher education, Bliss, Hilton, Wiley, and Thanos (2013), in a survey of over 125 students and 11 teachers from seven colleges, found that the majority of students and teachers were satisfied using open textbooks, valued the cost savings, and acknowledged the texts as being of high quality. These findings were supported in the results of a recently published survey: Senack (2014) reported that 82% of students said free online access to a textbook (with the option of buying a hard copy) would help them do “significantly better” in a course. Senack argues for widespread use of open textbooks, which he estimates can save students an average of $100 per course.

Open textbooks are basically a subset of open educational resources (OER) (Hilton et al., 2013). The past several years have seen an exponential increase in the creation and use of OER, which, according to an often-cited definition, are

teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge. (Atkins, Brown, & Hammond, 2007, p. 4)

Experts have recommended that teachers develop OER based custom-built open textbooks that meet their course needs instead of prescribing multiple proprietary textbooks (Bliss et al., 2013; Senack, 2014; Wiley, Green, et al., 2012). The OER based approach to open textbook development has three important benefits: Textbooks can be built upon existing OER rather than developing from scratch; because OER can be edited or abandoned at less cost than commercial adoption, teachers risk less when developing with vetted OER materials (Acker, 2011); and OER reduces the time lag between the development of textbooks and their delivery, and enables reuse, recontextualization, and customization to meet the course learning outcomes (Baraniuk, 2013).

Despite the diversity and obvious benefits of OER, the University of the South Pacific (USP) has yet to take full advantage of such open resources. USP is located in the hub of the Pacific Ocean; it is one of only two regional universities in the world, with over 27,000 students. The University is jointly owned by 12 member countries: Cook Islands, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. The academic schools, institutes and centres at the USP are organized into three faculties: the Faculty of Arts, Law and Education (FALE); the Faculty of Business and Economics (FBE); and the Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment (FSTE).

Amazingly, as an increasing number of higher education institutions around the globe are developing and offering open textbooks in an effort to increase their affordability, most USP teachers continue to prescribe traditional published textbooks to their students who find it difficult to afford. Bliss et al. (2013) state that students can save money with open textbooks only if teachers are willing to develop them. This background raises the question of whether USP teachers are willing to develop open textbooks for their courses. While there is no clear answer at present, there is anecdotal evidence of use of OER based learning resources and activities in some courses. It is, therefore, important to go beyond anecdotes in order to strategize possibilities for future development of OER derived custom-built open textbooks at USP. Hence, this study aims to assess USP teachers’ willingness towards development of custom-built OER derived open textbooks for their courses. This aim further focused on the following specific objectives:

In pursuit of the above objectives, the overall strategy was to survey USP teachers using a self-administered online questionnaire partly developed for this study and partly making use of questions from 2012 Faculty and Administrator Open Educational Resources Survey (Florida Virtual Campus, 2012).

Open textbooks and OER are a fairly new phenomenon at the USP. A descriptive study is adequate where the research area is relatively new or unexplored (Punch, 2005). Thus, this study adopted the descriptive (survey) study. As a descriptive study, no specific conceptual framework or theory was applied. According to Koul (2009), descriptive studies

constitute a primitive type of research and do not aspire to develop an organized body of scientific laws. Such studies, however, provide information useful to the solution of local problems and at times provide data to form the basis of research of a more fundamental nature. (p. 104)

This descriptive study thus sought to simply find out what the present situation is, with regard to open textbooks and OER, from the teacher perspective at the USP.

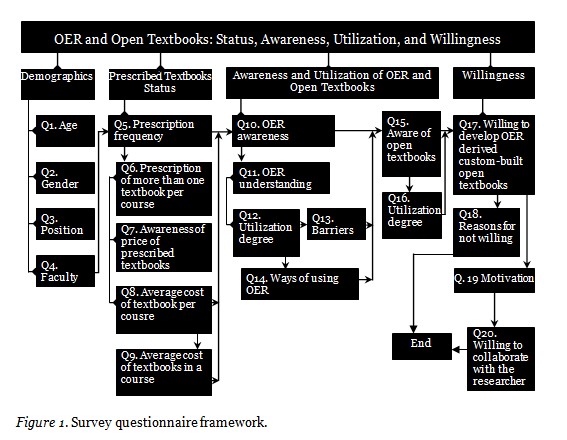

The first draft questionnaire was content validated by two international experts. Based on their comments, the final version of the questionnaire was drawn up, and was tried out/piloted on five USP teachers. From the feedback of the trial, expressions for two items were modified. The final questionnaire included 20 items divided into four sections: demographics, prescribed textbooks status, awareness and utilization of OER and open textbooks, and willingness towards OER derived custom-built open textbooks development. Figure 1 illustrates the questionnaire design. The questionnaire included skip logic or routing questions. Skip logic “refers to a respondent taking an alternative path through a questionnaire depending on his or her answer to an earlier question” (Schonlau, Fricker, & Elliott, 2002, p. 30). For example, as illustrated in Figure 1, a ‘no’ response to question 10, indicating that the respondent is not aware of OER, prompts the respondent to skip to question 15, past the questions related to OER understanding and usage. The questionnaire comprised both closed- and open-ended questions.

The target population for this study was 229 USP teachers including professors, associate professors, senior lecturers, lecturers, and assistant lecturers. These teachers were selected as they coordinate courses and have the authority to prescribe textbooks for their courses. A simple random sampling technique was used to draw 175 samples from the target population as it was the only technique allowing every element of the population the same probability of being selected, in turn reducing sampling bias (Muijs, 2004; Thompson, 2012).

This study was given ethical approval by the USP Research Office. The questionnaire was administered via the tool Google Forms. The primary author sent a hyperlink to the questionnaire along with introductory information through personalised e-mail to 175 university teachers at the USP, encouraging them to respond to the survey. They were informed that their participation in the survey was voluntary and that the survey would take 10-15 minutes to complete. E-mail addresses were obtained for all the participants from the USP website. The data were collected from November 20, 2013 to December 20, 2013. In order to increase the response rate, a reminder to complete the questionnaire was e-mailed on December 9, 2013.

The data gathered through the online questionnaire administered via Google Forms were exported to an MS-Excel worksheet for analysis based on the objectives of the study. The findings of the study are discussed in the next section.

Out of the 175 questionnaires distributed online, 39 teachers completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 22%. The results from the 39 questionnaires were analysed and are reported according to the four sections noted above: (A) teacher demographics, (B) prescribed textbooks status, (C) awareness and utilization of OER and open textbooks, and (D) willingness towards development of OER derived open textbooks.

Of the 39 teachers who completed the survey, 17 were lecturers, followed by assistant lecturers (n = 13), senior lecturers (n = 5), associate professors (n = 3), and subject coordinators (n = 1). The gender distribution of the respondents was 67% male (n = 26) and 33% female (n = 13). Fifty-one percent of the respondents were between 26 and 40 years old, 33% were between 41 and 55 years old, and the rest, 15%, represented age groups older than 56, with the mode falling in the 26–40-year age group. Of the total respondents, 15 each came from the FSTE and FBE, and 9 from FALE.

In the second section of the survey, questions were designed in such a way that the frequency of textbooks prescribed, frequency of more than one prescribed textbook per course, teachers’ awareness of the costs of the prescribed textbooks, and average cost of prescribed textbooks in a course could be revealed.

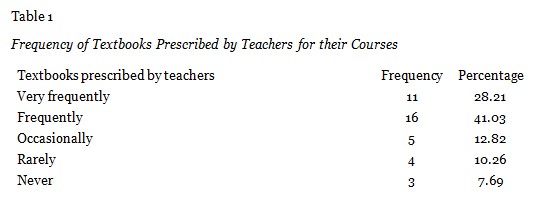

Teachers were asked how often they prescribed textbooks for their courses; the data showed that 36 out of 39 teachers were involved in the practice of prescribing textbooks. An inspection of Table 1 will further reveal that 69.24% (n = 27) of teachers ‘very frequently/frequently’ prescribed textbooks for their courses, while 23.08% (n = 9) ‘occasionally/rarely’ prescribed textbooks, and 7.69% (n = 3) ‘never’ prescribed textbooks for their courses.

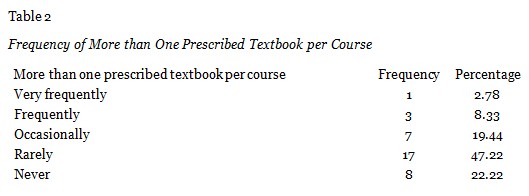

Those teachers (n = 36) who reported prescribing textbooks were asked how often they prescribed more than one textbook per course. As given in Table 2, 47.22% (n = 17) claimed that they rarely prescribed more than one textbook per course; a combined total of 30.56% (n = 11) reported ‘very frequent/frequent/occasional’ prescription of more than one textbook per course; and 22.22% (n = 8) of teachers stated that they never prescribed more than one textbook per course.

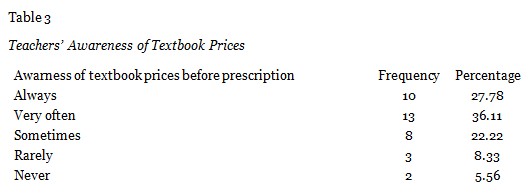

Teachers (n = 36) who prescribed textbooks were asked how often they were aware of textbook prices before prescribing them. It was found that 27.78% (n = 10) of teachers always knew textbook prices in advance, in contrast to 5.56% (n = 2) who were never aware of textbook prices before prescribing them for their courses (Table 3).

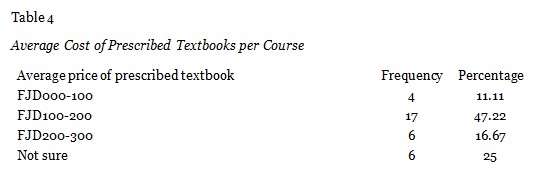

When asked the average amount students paid for prescribed textbooks in semester 2, 2013 courses, the majority (47.22%) of teachers reported that the average price of prescribed textbooks for their course was between FJD100 to FJD200 (1 FJD is equivalent to 0.55 USD), 16.67% reported average cost within the range of FJD200-300, 11.11% indicated average cost between FJD000-100, while 25% said that they were not sure of the price (Table 4).

The third section of the survey was designed to elucidate teachers’ awareness, understanding and utilization of OER, their views about barriers for using OER and types of challenges they face while using OER, and to identify their awareness and use of open textbooks. These data shall be useful in drawing appropriate plans for facilitating use of OER for developing open textbooks.

To guage awareness and understanding of OER, teachers were first asked about the former. From the total 39 teachers, 82% (n = 32) affirmed that they were aware of OER, while 18% (n = 7) admitted that they were not aware of OER. To guage understanding, those teachers (n = 32) who claimed to be familiar with OER were then asked to explain what the term OER meant to them. Open responses indicated that the majority of teachers who claimed knowledge of OER basically had a fair understanding of the OER concept, though without much in-depth erudition on its benefits and convolutions. Below are some of the more precise responses:

Open educational resources - free online resources that can be freely used in the development of a course without infringing copyright.

OER to me is pathway to achieve Education for All.

Free educational materials available online.

Educational materials that are accessible to and can be used by the general public for free of charge.

Resources that can be used for teaching & learning as well as for research purposes and are available free and freely accessible.

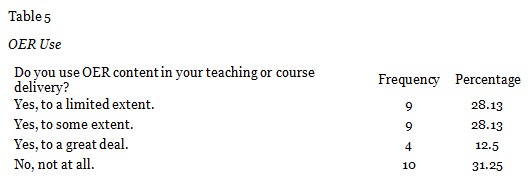

Teachers (n = 32) who claimed familiarity with OER were asked whether they used OER content in their teaching or course delivery. Regardless of their familiarity with OER, 31.25% (n = 10) reported to have never used OER, while of the 68.75% (n = 22) who claimed to have used OER, only 12.50% (n = 4) utilized OER to a great extent (Table 5).

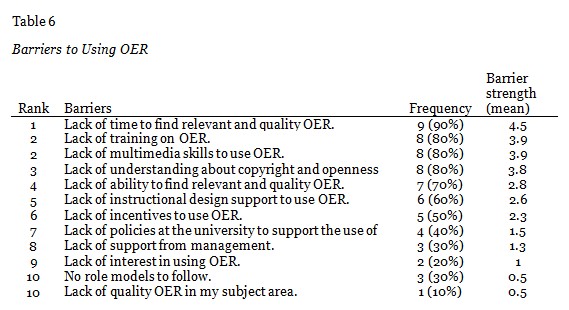

Those teachers (n = 10) who reported awareness of OER but having never used them were asked to identify and rate what they considered to be the most significant barriers to OER use from a list of 12 barrier statements; these are summarized in Table 6 in rank order, frequency, percentage, and barrier strength on a scale of ‘1’ (strongly disagree) to ‘5’ (strongly agree). The greatest barriers identified were time limitations restricting accessing relevant OER, inadequate training on OER, insufficient multimedia skills to use OER, uncertainties over copyright-related practices, and difficulties with finding appropriate and quality OER. This was followed by lack of instructional design support and incentives to use OER. Lack of OER policies, insufficient support from management, lack of role models, and lack of quality OER were the bottommost barriers.

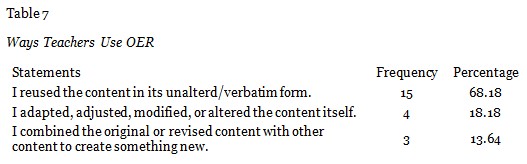

Amongst the teachers (n = 22) using OER, it was found that 68.18% (n = 15) were involved in the practice of reusing OER content in its original form, while 18.18% (n = 4) were revising the content, and only 13.64% (n = 3) were remixing the content with other open content to create something new (Table 7). This exhibits that USP teachers are more comfortable with using OER in an ‘as is’ form. This situation may exist due to their lack of ability to repurpose OER for more contextualized use.

Those teachers (n = 22) who had used OER were asked to describe challenges they most often encountered during its use. The challenges disclosed were common to the top four ranked barriers to using OER, namely, insufficient time to search for OER, lack of knowledge about OER, confusion with open licenses, and software compatibility issues. Conversely, three teachers reported that they did not face any difficulty using OER. Upon further investigation, the data revealed that these teachers (n = 3) were primarily involved in the practice of reusing OER in its original form and using OER to a limited extent. This suggests that these teachers may most likely come across hurdles once they start making frequent use of OER.

Teachers were asked to indicate their familiarity with open textbooks. To ensure accurate interpretation, the questionnaire included a definition of “open textbook” as follows:

Open Textbooks are freely accessible digital textbooks that can be read online, self-printed or download via any computer with Internet access at no or low cost. In addition, students may often be able to order a commercial “print on demand” copy of an open textbook at a modest cost. (Florida Distance Learning Consortium, 2011)

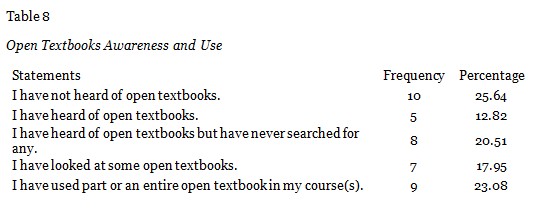

From Table 8, it is revealed that 25.64% (n = 10) of teachers were not aware of open textbooks compared with a majority 74.36% (n = 29) who were. Among those who were aware of open textbooks, 23.08% (n = 9) reported having used part of or an entire open textbook in their courses. Teachers who reported having used open textbooks were further asked to list the course(s) in which they had used open textbooks and to indicate whether they had used part of or an entire open textbook. The results reveal that 12 open textbooks were utilized in 12 courses and further show that, of these 12 open textbooks, one entire and two partial open textbooks were used in three postgraduate courses, while three entire and six partial open textbooks were used in nine undergraduate courses. This demonstrates that some USP teachers are using open textbooks to some extent, though their utilization of open textbooks may be confined to ‘as-it-is’ use.

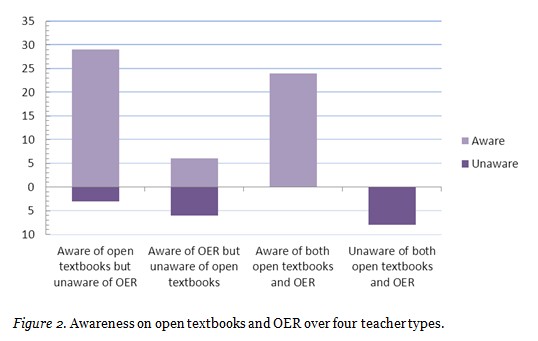

The overall response to this question was quite surprising. The data showed four teacher types: those aware of both OER and open textbooks; aware of one but not the other; or unaware of either, as Figure 2 illustrates. Out of 29 teachers who reported to know about open textbooks, three of them had earlier reported that they were not aware of OER. In contrast, six teachers who had previously reported to know about OER were not aware of open textbooks, while 24 teachers were aware of both open textbooks and OER, and eight were unaware of both. These results offer compelling evidence that some USP teachers lack awareness in regards to the diversity of OER and confirm that most have surface-level understanding of the concept of OER.

The final section of the survey was designed to identify teachers willing to develop OER derived custom-built open textbooks for their courses. Those teachers who were willing to develop were asked to identify possible motivating factors, while the unwilling teachers were asked to give reasons for their unwillingness. Such information shall be useful in formulating strategies for preparing teachers for OER based custom-built open textbook development.

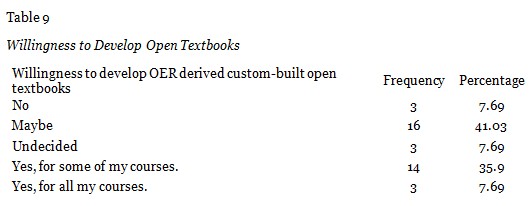

As Table 9 illustrates, 43.59% (n = 17) of teachers reported they planned to develop custom-built OER derived open textbooks for some or all of their courses in the near future, while a small minority of 7.69% (n = 3) said that they would not be willing to develop custom-built OER derived open textbooks for their courses. A combined total of 48.72% (n = 19) for ‘maybe’ and ‘undecided’ reflected teachers’ indecisiveness towards development of OER derived custom-built open textbooks. Upon further analysis, the data revealed that amongst the willing teachers (n = 17), 11 of them were aware of both OER and open textbooks, two were unfamiliar with either, one knew about open textbooks but did not know about OER, and three were aware only of OER prior to the survey. The significance of this revelation is that it demonstrates teachers who prior to this survey were unacquainted with OER or open textbooks are still willing to develop OER derived open textbooks. It appears that the survey acted as a medium to introduce the potential of OER and open textbooks to those who were previously uninformed.

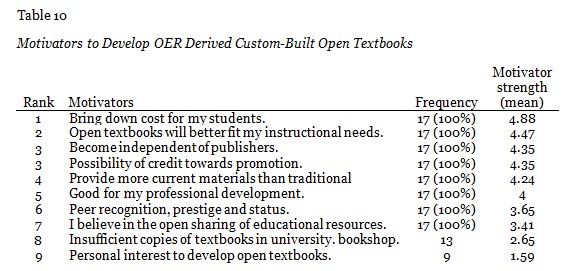

Those teachers (n = 17) who stated willingness to develop open textbooks were asked to identify and rate the strength of motivating factors that influenced their decision from a preselected list of 10 possible motivator statements. Table 10 outlines the frequency, percentage, motivator strength, and the rank of these 10 items. As illustrated, on a scale of ‘1’ (strongly disagree) to ‘5’ (strongly agree), the motivator strength ranged from a high of 4.88 for the item ‘Bring down cost for my students’ to a low of 1.59 for the item ‘Personal interest to develop open textbooks’.

Those teachers (n = 3) who said that they would not be willing to develop custom-built OER derived open textbooks for their courses were asked to provide explanations for their decisions. Exact responses from each teacher are given below.

Teacher 1: I’m not convinced that the content that we teach are not being addressed through joint use of prescribed texts and supplemental books.

Teacher 2: It’s all dependent on time as most of us are very busy given our own workload.

Teacher 3: I am still not sure about copyright issues and how much I can use online text books. I would like to have these questions answered before I use this in my courses.

The intention of this item was to identify teachers with whom the primary author could collaborate to initiate an OER derived open textbook development project at the USP. Teachers (n = 17) who conveyed their willingness to develop custom-built OER derived open textbooks for some or all of their courses were asked whether they would be interested in collaborating with the primary author to develop custom-built OER derived open textbooks for their course(s). Out of 17 expectant teachers, 13 teachers affirmed that they would be willing to cooperate with the primary author, while four declined. Teachers who answered affirmatively were asked to email the primary author for further discussions. All 13 agreeable teachers emailed the primary author, expressing their interest in working together for the development of OER derived open textbooks for their course(s).

Bliss et al. (2013) claimed that significant cost savings are possible by displacing traditional publisher textbooks with open textbooks; however, they also cautioned that students can save money with open textbooks only if teachers are willing to develop them. In light of this postulation, this paper is a modest contribution toward the ongoing discussions on OER and open textbooks. The present study has made an attempt to assess the state of prescribed textbooks and possibilities to initiate custom-built OER derived open textbook development at the USP.

In regard to textbooks, it was found that 92.30% (36/39) of USP teachers prescribed publisher textbooks for their courses. As expected, 28 of them were involved in the practice of prescribing more than one textbook per course. Mostly, the average cost of textbook per course was found to fall in the range of FJD100-200 (1 FJD is equivalent to 0.55 USD). Not surprisingly, only 10 out of 36 teachers were found to be consistently aware of the price of textbooks before prescribing them for their courses. In the light of these findings, we estimate that USP students are likely to spend approximately FJD400 on textbooks each semester.

Regarding OER awareness, while most teachers had heard of the term OER, most lacked a clear understanding of its concept. Out of 39 teachers, 82% (n = 32) conveyed that they knew about OER. However, closer examination of the results revealed that six out of the 32 teachers who reported familiarity with OER were not aware of open textbooks, while three out of seven who had not heard of OER were aware of open textbooks. On the other hand, amongst the total 39 teachers, 29 (74%) knew of open textbooks, but three did not know about OER, while amongst the 10 who had not heard of open textbooks, six knew about OER. These findings indicate that there are four types of teachers at USP: those aware of both OER and open textbooks (two types); aware of one but not the other; or unaware of either. The analysis confirms that some USP teachers are not well versed with the concept of OER. This finding is consistent with those of Chen and Panda (2013) who found that most teachers “were acquainted with OER, but at a rather superficial level, without much in-depth understanding of the intricacies involved in it” (p. 13). In their study, they found teachers were not familiar with different types of resources available as OER, which seems to be the case at USP. This calls for OER awareness raising initiatives at USP.

Regarding utilization of OER and open textbooks, only limited use was found. Of the 32 teachers who knew about OER, 22 used OER, and of these, only four utilized it to a great extent. Similar results were reported by Gunness (2011). The findings of the current study show that teachers mainly used OER in unaltered forms. With regard to open textbook usage, while increasing adoption by teachers was encouraging, the number of teachers using open textbooks remains small, with only 23.08% (9/39) of teachers found to have used open textbooks. Limited use of open textbooks was also reported in the 2012 Faculty and Administrator Open Educational Resources Survey (Florida Virtual Campus, 2012). USP teachers’ lack of awareness and understanding of OER and open textbooks is likely a reason for this low extent of utilization.

Turning to the question of what inhibits teachers from using OER, this study found that lack of time to find relevant and quality OER, insufficient training, inadequate multimedia skills, confusion over copyright-related matters, and lack of ability to find relevant and quality OER ranked as the top-most barriers. Those teachers who were using OER encountered similar obstacles. This finding is in agreement with Atenas, Havemann, and Priego (2014), who showed that time consumption, search ability, lack of training, licensing issues, and technical skills were the main barriers. Interestingly, lack of OER policies as a barrier to using OER was ranked only seventh and thus much lower than previous research has reported (Andrade et al., 2011). Nevertheless, on reflection, all the top-ranking barriers had a skill element incorporated within them. It could be argued that the teachers were more concerned about ‘know-how’ of using OER than policy matters, meaning that continuous training and support is required in order to widen participation in OER practice at USP.

The results showed that a high proportion of the USP teachers surveyed are willing to develop OER derived custom-built open textbooks for their courses. Amongst the total 39 teachers who responded to the survey, 43.59% (n = 17) showed willingness towards OER derived open textbook development, and 13 of these 17 teachers are willing to jointly work together with the primary author to develop OER derived open textbooks for their courses. These teachers appear keen in developing open textbooks for their courses to address textbook affordability despite a lack of incentives and absence of an OER policy at the USP. The list of motivating factors identified in the current study was in line with a previous study by Pegler (2012). The current study reveals that reducing cost for students, customizability to meet instructional requirements, becoming independent of publishers, and possibility of credit towards promotion are the dominant motivating factors to teachers.

The most striking result to emerge from the study is that amongst the 17 teachers who affirmed their intention to develop OER derived open textbooks, two were aware of neither OER nor open textbooks, one was familiar with open textbooks but did not know about OER, and three were aware only of OER prior to the current study. This finding was unexpected, indicating that the current study made them aware of the concept and potential of OER which may have influenced their decision. Also it could be that the motive for these teachers to become engaged in open textbook development is for publicity and to gain first-mover advantage (OCED, 2007).

Bliss et al. (2013) noted that students can save money with open textbooks only if teachers are willing to develop them, and the fact that a good number of teachers (n = 17) are willing to do so for their courses is a good indicator to start open textbook initiatives at USP. One approach to kick-starting such an initiative is to begin by developing one textbook at a time (Morris-Babb & Henderson, 2012). The primary author is currently working with nine USP teachers to develop a custom-built OER derived open textbook for a postgraduate course entitled “AL400 Research Methodologies in the Humanities and Social Sciences”. These nine teachers team teach this course and were identified as a result of this study. In actuality, the coordinator of this course was one of those teachers who agreed to cooperate with the principal author to develop an OER derived custom-built open textbook for his course. Later, the course coordinator convinced the rest of the teaching team to join the project. Apart from producing an open textbook, the result of the ongoing project is anticipated to provide design principles and ‘how-to’ guidelines for developing custom-built OER derived open textbooks to the teachers of the case study university. The experiences of this project will be disseminated through future publications and shall be built on the research findings reported in this paper.

Acker, S. R. (2011). Digital textbooks: A state-level perspective on affordability and improved learning outcomes. Library Technology Reports, 47(8), 41–52.

Allen, N. (2011). High prices prevent college students from buying assigned textbooks. Student PIRGs. Retrieved from http://www.studentpirgs.org/news/ap/high-prices-prevent-college-students-buying-assigned-textbooks

Andrade, A., Ehlers, U.-D., Caine, A., Carneiro, R., Conole, G., Kairamo, A.-K., … Holmberg, C. (2011). Beyond OER: Shifting focus to open educational practices. Due-Publico, Essen. Retrieved from http://www.oerasia.org/OERResources/8.pdf

Atenas, J., Havemann, L., & Priego, E. (2014). Opening teaching landscapes: The importance of quality assurance in the delivery of open educational resources. Open Praxis, 6(1), 29–43.

Atkins, D. E., Brown, J. S., & Hammond, A. L. (2007). A review of the open educational resources (OER) movement: Achievements, challenges, and new opportunities. Retrieved from http://www.hewlett.org/uploads/files/ReviewoftheOERMovement.pdf

Baraniuk, R. G. (2013). Opening education. The Bridge, 43(2), 41–47. doi:10.1126/science.1168018

Bliss, T., Hilton, J., Wiley, D., & Thanos, K. (2013). The cost and quality of online open textbooks: Perceptions of community college faculty and students. First Monday, 18(1). Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3972/3383

Carpenter, P., Bullock, A., & Potter, J. (2006). Textbooks in teaching and learning. Brookes eJournal of Learning and Teaching, 2(1). Retrieved from http://bejlt.brookes.ac.uk/paper/textbooks_in_teaching_and_learning-2/

Chen, Q., & Panda, S. (2013). Needs for and utilization of OER in distance education: a Chinese survey. Educational Media International, 50(2), 77–92. doi:10.1080/09523987.2013.795324

Florida Distance Learning Consortium. (2011, September). Florida student textbook survey. Tallahassee, FL: Author. Retrieved from http://www.openaccesstextbooks.org/%5Cpdf%5C2010_FSTS_Report_01SEP2011.pdf

Florida Virtual Campus. (2012, August). 2012 faculty and administrator open educational resources survey. Tallahassee, FL: Author. Retrieved from http://www.openaccesstextbooks.org/%5Cpdf%5C2012_Faculty-Admin_OER_Survey_Report.pdf

Graydon, B., Urbach-Buholz, B., & Kohen, C. (2011). A study of four textbook distribution models. Educause Quarterly, 34(4). Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/study-four-textbook-distribution-models

Gunness, S. (2011). Learner-centred teaching through OER. In A. Okada (Ed.), Open educational resources and social networks: Co-learning and professional development. London: Scholio Educational Research & Publishing. Retrieved from http://oer.kmi.open.ac.uk/?page_id=2329

Hallam, G. (2012). Briefing paper on eTextbooks and third party eLearning products and their implications for Australian university libraries. Retrieved from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/55244/3/55244P.pdf

Hilton, J., Gaudet, D., Clark, P., Robinson, J., & Wiley, D. (2013). The adoption of open educational resources by one community college math department. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(4). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1523/2652

Hilton, J., & Wiley, D. (2011). Open-access textbooks and financial sustainability: A case study on Flat World Knowledge. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(5). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/960/1860

Koul, L. (2009). Methodology of educational research (4th ed.) VIKAS Publishing House Pvt Ltd.

Morris-Babb, M., & Henderson, S. (2012). An experiment in open-access textbook publishing: Changing the world one textbook at a time. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 43(2), 148–155. doi:10.3138/jsp.43.2.148

Muijs, D. (2004). Doing quantitative research in education with SPSS. London, GBR: SAGE Publications Inc. (US). Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/lib/unisouthernqld/docDetail.action?docID=10080884

OCED. (2007). Giving knowledge for free: The emergence of open educational resources. Paris. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/38654317.pdf

Okamoto, K. (2013). Making higher education more affordable, one course reading at a time: Academic libraries as key advocates for open access textbooks and educational resources. Public Services Quarterly, 9(4), 267–283. doi:10.1080/15228959.2013.842397

Pegler, C. (2012). Herzberg, hygiene and the motivation to reuse: Towards a three-factor theory to explain motivation to share and use OER. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1–18. Retrieved from http://www-jime.open.ac.uk/jime/article/viewArticle/2012-04/html

Perry, M. (2012). The college textbook bubble and how the “open educational resources” movement is going up against the textbook cartel. American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved January 03, 2014, from http://www.aei-ideas.org/2012/12/the-college-textbook-bubble-and-how-the-open-educational-resources-movement-is-going-up-against-the-textbook-cartel/

Punch, K. (2005). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Inc. (US).

Schonlau, M., Fricker, R. D., & Elliott, M. N. (2002). Conducting research surveys via e-mail and the Web. Santa Monica, CA, USA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/lib/unisouthernqld/docDetail.action?docID=10425077

Senack, E. (2014). Fixing the broken textbook market: How students respond to high textbook costs and demand alternatives. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.washpirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/1.27.14 Fixing Broken Textbooks Report.pdf

Thompson, S. K. (2012). Wiley Desktop Editions: Sampling (3rd ed.). Somerset, NJ, USA: Wiley. Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/lib/unisouthernqld/docDetail.action?docID=10630536

Wiley, D., Green, C., & Soares, L. (2012). Dramatically bringing down the cost of education with OER. Center for American Progress. Retrieved October 13, 2013, from http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/labor/news/2012/02/07/11167/dramatically-bringing-down-the-cost-of-education-with-oer/

Wiley, D., Hilton, J. L., Ellington, S., & Hall, T. (2012). A preliminary examination of the cost savings and learning impacts of using open textbooks in middle and high school science classes. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1153/2256