|

Marguerite Koole

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

This paper outlines a preliminary study of the kinds of strategies that master students draw upon for interpreting and enacting their identities in online learning environments. Based primarily on the seminal works of Goffman (1959) and Foucault (1988), the Web of Identity Model (Koole, 2009; Koole and Parchoma, 2012) is used as an underlying theoretical framework for this research study. The WoI model suggests that there are five major categories of “dramaturgical” strategies: technical, political, structural, cultural, and personal-agential. In the data collection, five online master of education students participated in semi-structured, online interviews. Phenomenography guided the data collection and analysis resulting in an outcome space for each strategy of the WoI model. The study results indicate that online learners actively employ a variety of strategies in interpreting and enacting their identities. The outcome spaces provide insights into ways in which online learners can manage their identity performances and strategies for ontological re-alignment (reconceptualization of oneself). Further study has the potential to elucidate how learning designers and online instructors might facilitate such identity-work in order to shape productive online environments.

Keywords: Digital identity; relational learning; online interaction

Learners today navigate through physical and virtual environments with apparent ease. These environments offer a variety of social networking opportunities through which participants can accumulate, exchange, create, and integrate new information into their personal narratives. Yet, learners still report feeling isolated and disconnected in these environments (McInnery & Roberts, 2004). How can today’s itinerant learners develop a sense of identity and affiliation within such communities? To answer this question, the researcher draws upon her previous work on the Web of Identity (WoI) model (Koole, 2009) which outlines strategic techniques for interpreting and enacting identities. The goal of this phenomenographic-style study is to explore the extent to which these strategies are experienced in a given online learning community, and how strategy enactment contributes to the development of self and affiliation. It is intended that the outcome of this short study will form a basis upon which to structure a larger study of identity positioning and relational dialogue in online learning.

This paper is grounded in a social constructionist perspective which holds that individuals socially create and negotiate an understanding of who they are with relation to shared knowledge, beliefs, and behaviours (Berger and Luckmann, 1966; Burr, 2003; Hacking, 2000). To help orient the reader to constructionism (with an « n »), it can be contrasted with constructivism (with a « v »). Social constructivism emphasizes mental processes in which an individual constructs his/her understanding of « reality ». These mental processes are influenced by internalized understanding of « societal conventions, history and interaction with signifcant others » (Talja, Tuominen and Savola, 2005, p. 81). Constructionism, however, emphasizes discourse as the primary mechanism through which an individual actively and contingently constructs and positions him/herself in relation to the world; that is, how one continually shapes his/her identity. Within this philosophical position, dialogic interaction is a significant focus of this research and the WoI model. Talja, Tuominen and Savola (2005) describe this dialogic theory well: « Constructionism sees language as constitutive for the construction of selves and the formation of meanings » (p. 89).

The social constructionist perspective is of great importance because it highlights the perspective taken on identity itself: that identity is not a characteristic inherent within the individual alone; rather identity is a fluid process shaped by the individual, the world, and the people with whom s/he interacts. Many other theories of identity are heavily focused on internal mental/psychological processes (such as Erikson’s [1968] stages of development, Marcia’s [1966] identity status theory [see Schwartz, Luyckx, and Vignoles, 2011]). Rather than taking an internal, psychological perspective, social constructionism asks us to consider how the learner and the community within which s/he interacts co-construct identities.

Macfayden (2008) suggests that “establishment of learner identities allows the development of a learning community” (p. 560). Goodyear and Zenios (2007) also recognize the relationship between identity, community, and learning:

A strong element of this socio-cultural view of learning is that participation in authentic knowledge-creation activities, coupled with a growing sense of oneself as a legitimate and valued member of a knowledge-building community, is essential to the development of an effective knowledge-worker. Action and identity are key. (p. 355-356)

Many definitions of community strongly support the notion that members should have a shared sense of history, purpose, norms, hierarchy, ritual, sense of belonging, and continuity (Lapadat, 2007; Schwier, 2007; Rovai, 2002). In other words, in order to more easily exchange and build upon ideas, it is helpful if learners share a common language, culture, and intellectual heritage. Online and offline, the social constructionist perspective suggests that it is through interaction, particularly “relational dialogue,” that learners express their dispositions, commonalities, and difference—their identities and affiliations (Ferreday, Hodgson & Jones, 2006, p. 224). This sense of selfhood and community, as noted by Ricoeur (1992), involves the sense of both self (idem—temporal continuity) and selfhood (ipse—differentiation of an individual from others in a given community).

Some researchers have posited that online interaction reduces social inequalities. It can, however, be difficult to mask some personal and cultural characteristics (such as gender) through sustained interaction because of unconscious habits and interaction styles (Ferreday, et. al., 2006; Chayko, 2009). Such habits might include writing styles, turns of phrase, metaphors frequently used, common typos, and spelling errors—to name a few. Walther’s (1996) research into asynchronous, text-based online conferencing led him to conclude that online interactions can, indeed, provide in-depth impressions of identities (hyper-personal), but requires more time and different techniques to decipher. Therefore, we can theorize that, online or offline, dialogic interaction between people takes place, but is guided by and transformed through the affordances, the “range of possible activities” (Norman, 1999, p. 41) of the available tools.

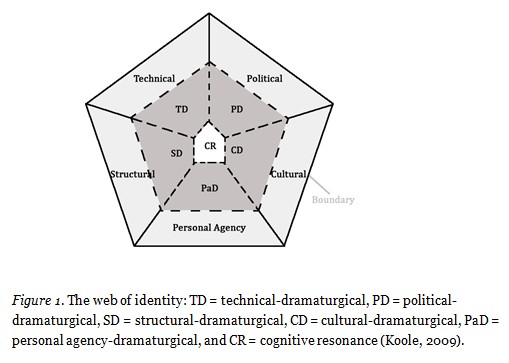

Based on Goffman’s (1959) impressions management perspectives and Foucault’s (1988) technologies of the self, the Web of Identity model (WoI) is a heuristic for exploring different aspects of identity performance in both physical and virtual settings. The outer ring (light grey) in Figure 1 shows five perspectives through which participants view performances. The inner ring (dark grey) represents the observable enactments of the perspectives—that is, the dramaturgical strategies (terminology from Goffman’s [1959] « dramaturgical theory » in which he saw interaction as similar to a theatrical performance). Such strategies may be viewed as epistemic games, the socially negotiated ways of expressing the perspectives (Collins, 1993). The centre of the model, cognitive resonance (CR), is the point at which an actor interprets behaviours of others, adjusts strategies, and makes sense of the world.

The mechanism underlying the individual’s move towards CR is based upon Festinger’s (1966) theory of cognitive dissonance. To explain this theory, one must first understand how he defines « cognition ». His use of the term cognition refers to « any knowledge, opinion, or belief about the environment, about oneself, or about one’s behavior » (p. 3). He then introduces the notion of dissonance: « the existence of nonfitting relations among cognitions » (p. 3). This is a significant factor in the WoI model: when individuals move from consonance to dissonance, they will seek to re-establish consonance. The process of re-establishment has been labelled « resolution ». Individuals may resolve dissonance through a variety of strategies such as altering how they act, changing their opinions, declining or avoiding interaction; these strategies shape identity.

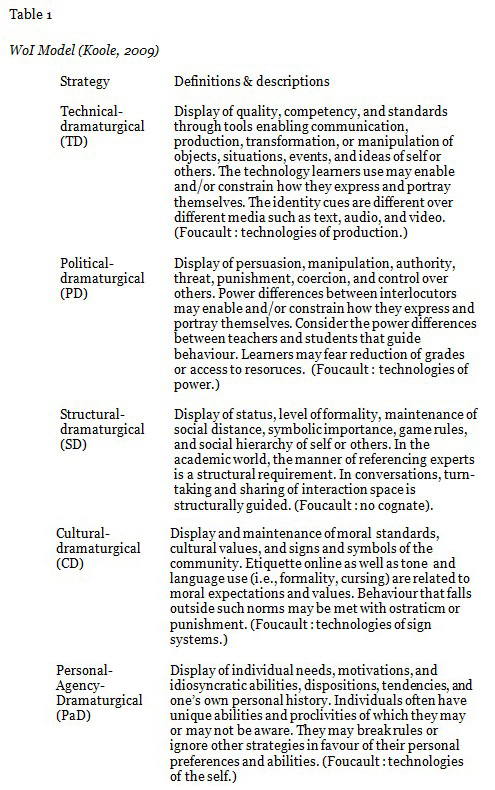

Figure 1 is a graphical representation of the WoI process. In adjusting CR, the individual formulates reactions that are then expressed (pushed back) through the dramaturgical strategies (dark grey) and which may, in turn, influence the perspectives (light grey). (The dotted lines in the model symbolize the permeability. It is a complex, iterative, and continual process involving dialogic and symbolic exchange [Koole & Parchoma, 2012]). Table 1 describes the strategies of impressions management corresponding to the middle ring (dark grey) in Figure 1. The terminology has been derived primarily from that of Goffman (1959). Foucault’s (1988) terminology is indicated in parentheses.

Several strategies may be used in a given situation and expression of any one strategy may trigger the use of another. Enactment of strategies and reactions to enactments are constantly transformed and interpreted through the model.

In this process, individuals constantly evaluate their “personal epistemology” (one’s beliefs about the world) against the apparent epistemology of others (Goodyear & Zenios, 2007, p. 363). In other words, individuals compare what they believe about the world and what they expect of the world with what they observe others doing and saying. Expression of WoI techniques shapes the coordination of activity, emotional states, and views of self and group history. The constant adjustment of epistemology in the centre of the model (CR) may be related to an individual’s epistemic fluency—that is, the agility with which an individual can adopt and/or adapt behaviours and, possibly, beliefs about new conditions within a given social context (Goodyear & Zenios, 2007). When an individual and members of his/her community share an understanding of their collective and individual identities, the individual approaches a more harmonious level of resonance (Chayko, 2008). In contrast, individuals may reach points at which their concept of self or belonging are in conflict with the strategies enacted. Such conflict may result in rejection and/or ontological adjustment of concepts of self or community (Koole & Parchoma, 2012). This space of liminality (a position between dissonance and resolution) can be thought to be somewhat similar to Land, Cousin and Meyer’s (2005) conception of a [concept] threshold point—a point at which dissonance becomes so great that the individual must readjust. In identity terms, we might call this a self-concept threshold.

Support for the premises of the WoI model may be found in the relational self theory (Chen, Boucher, and Tapias, 2006) which describes how individuals develop representational models of others, internalize them and develop a repertoire of selves that they can enact when interacting with different people. These selves provide « positive and negative self-evaluations, affect, goals, self-regulatory strategies, and behaviours » (Chen, Boucher, and Kraus, 2011, p. 154). Chen et al. suggest that additional research needs to be done to identify « moderators of transference », that is, « modering variables that make transference and other phenomena associated with the activation of significant-other representations more or less likely to occur » (p. 168). What the WoI model provides is a breakdown of the strategies, moderating variables, that individuals can use to model their identities and decipher the identities of others.

The main questions the author seeks to answer in this study include: How do learners experience each WoI strategy? Do learners adjust these strategies to attain cognitive resonance? An additional underlying goal is to ascertain the value of the theoretical model: does the WoI provide a lens through which researchers can gain deeper understanding of how learners shape and reshape their online identities?

To explore the ways in which learners experience cognitive resonance and the WoI strategies, the researcher chose to use phenomenographically-inspired methodology. Marton and Pong (2005) define phenomenography as an investigation of “the qualitatively different ways in which people understand a particular phenomenon or an aspect of the world around them” (p. 335). Phenomenography appears commensurate with the investigation of WoI actions from the point of view that phenomenographers regard experience as a result of interaction between the individual experiencing and the phenomenon experienced (Åkerlind , 2005); in the WoI model, identity develops from the interaction between the individual experiencing strategies and their expression of strategies in response. Phenomenography allows the researcher to explore participants’ descriptions (from a second-order perspective), how individuals experience strategies, express strategies, and the resulting adjustments, though ephemeral, in cognitive resonance-seeking.

In keeping with phenomenography’s emphasis on context in shaping experience (Marton & Pong, 2005; Svensson, 1997), the interview questions focused on eliciting narrations and viewpoints of online interactions such as conflict, support, and sharing, and how those interactions might affect perceptions of identity.

Once research ethics permission was acquired, the researcher solicited volunteers amongst students in a Master of Education course taught entirely by distance. The researcher recorded the interviews using a synchronous tool, Elluminate®. The researcher then transcribed the recordings. The transcripts were redacted, removing any names or other comments that might identify any individuals. The participants were given an opportunity to review the transcripts and encouraged to add any additional thoughts and corrections to the transcripts.

According to Åkerlind (2005), the steps in phenomenographic data analysis include: 1) reading and re-reading transcripts, 2) searching for variation of experience, and 3) searching for structural relationships between variations of experience. Analysis is highly iterative and involves constant comparison yielding categories with a complete set of possible ways of experiencing the target phenomenon. This was the procedure followed in this study.

Because the researcher was an employee of the master’s program from which the participants were sampled, the participants may have felt the need to soften their accounts of conflict and performance of others in the program. No deception was used; the learners were apprised of the fact that this was a pilot project and that their identities would remain confidential. The study was fully approved by the institutional research ethics board.

Whilst the goal of phenomenographic research is to achieve a complete picture of variation, the results can never be completely representative of all the different ways of conceptualizing or experiencing a phenomenon (Åkerlind, 2005). Because of the scope of this initial research project, the variation represented in the results is limited in accordance with the number of participants. Generally, it is recommended that phenomenographic studies involve 15 to 20 participants (Trigwell, 2000). This preliminary study involved only five. Additional studies should be done in order to more fully examine the variation of experience. Finally, the results may not necessarily be generalized to other programs or institutions as the participants are all members of the same master’s program, which may, itself, be idiosyncratic.

Five participants were interviewed, four female and one male: P2, P4, P5, P6, and P7. They described themselves as a teacher, consultant, full-time parent, and two as instructional designers. All were enrolled in the same Master of Education program. They reported to have taken at least two online courses and had some experience with the social networking environment. Most of the interactions with classmates were restricted to the class discussion boards. Four participants indicated having developed a closer relationship with one or two fellow students, leading to email, Skype, or face-to-face contact. The results below outline the main categories of experience for each strategy and CR, accompanied by examples of the variety of ways in which they were experienced.

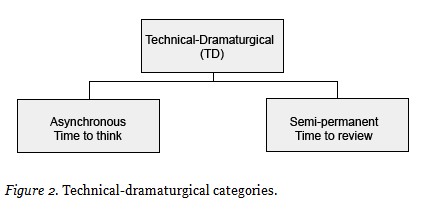

Figure 2 illustrates the main TD categories expressed by the participants. Although the technologies enable rapid responses, all participants felt that the asynchronous environment allows them to carefully consider the messages of others as well as script, edit, and reedit their own responses, cautiously avoiding “knee-jerk reactions” and inappropriate tone. P5 indicated having an online identity that is “extremely scripted,” carefully stripped of “spontaneous expressions of . . . thoughts or feelings”. For both P4 and P5, the semi-permanent nature of the online environment necessitated such scripting. P5 commented, “I’m very cognizant of the fact that once it’s there, it’s there. So, I’m careful in that respect.”

The semi-permanence of online interactions also meant that past interactions could be re-examined. When discussions or values did not resonate, P2, P4, and P7 tried to glean additional information from the messages and profiles of the other learners. P4 reflected, “Even if it’s not a picture of the person, um, if they’ve chosen something else, that kind of shows you what they value.”

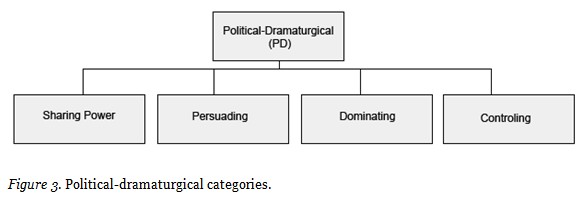

The PD strategies fit on a continuum starting with encouragement (sharing power) and extending through persuasion, dominance, and control. All participants indicated that they both gave and received encouragement. P6 noted, “Throughout discussions, I have had people comment that they’ve appreciated the discussion and I take that as encouragement, regardless of their views.” Sharing of power also took the form of information sharing—especially when a fellow student did not appear to understand something. P6 reported “filling in the person, so they have a little better context.”

P6 was “cynical” about the effectiveness of persuasion and took a cautious approach in discussions,

“I certainly try to persuade others. I am careful to ensure that my comments are phrased in such a way that it is clear that I am criticizing ideas rather than people . . . to maintain not only my dignity, but the dignity of [others].”

This approach was reflected by P4 who said, “I’ve actually never felt that people tried to persuade me. They’ve always sort of shown a different viewpoint, and then leave it up to you to draw your own conclusions.” P5 noted that professors and students attempted to persuade each other. P7 commented, “Yeah, I think they’ve persuaded me to [consider] their viewpoints—whether I’ve adopted them, maybe not.” According to these accounts, persuasion was often enacted through respectful sharing of ideas.

Dominance, itself, was seen as aggressiveness in tone and argument, forcing viewpoints, “always” posting messages first, posting large numbers of messages, and asking “all the questions.” P5 recounted a story of how another student’s work was “torn apart” by another. The student who levied the critique justified her actions by positing her authority in the subject. Reactions to such aggression varied from non-responsiveness (P7: “I just become silent”) to the use of backchannel communications such as private emails to the aggressor, the professor, or the other students in an attempt to control behaviour. P7 reported, “I did privately say in an email that it was not appropriate and that the tone needed to be changed.” Digressions in class discussions, unmanageable numbers of messages, and personal attacks—albeit rare—were expected to be controlled by a moderator or instructor in a power role.

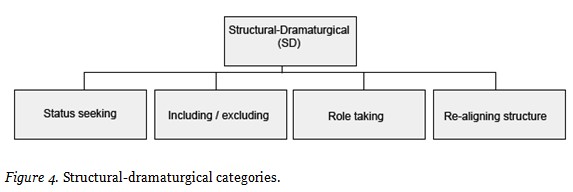

Clearly the quest for and maintenance of status is the most significant characteristic of the SD strategy. When asked about the most important or influential person in a discussion, participants referred to those with knowledge and expertise, those who seemed “articulate” and “well-read,” and those with “better ideas.” Receiving numerous responses and acknowledgement from the instructor was also an indicator of importance—popularity superseding quality of ideas. Lack of responses tended to be interpreted as lack of worthiness. P4 suggested, “You feel like you’re getting picked last for gym.” Those deemed least influential were described as those who lacked presence, posting rarely or late in the discussions.

For some participants, signs of familiarity amongst others gave them a sense of being excluded, and hence, of lesser status. P2 pondered, “Sometimes, I wonder whether they’ve had a previous relationship . . . with the prof . . . because sometimes some profs, when they respond to postings, will use people’s [first] names.” P5 admitted to having unintentionally excluded others: “A specific example of that is my friend and I, who take courses together, I think sometimes inadvertently, uh, create a conversation that is only two-ways between she and I, that other people may feel excluded.”

A great variety of roles were recognized including the leader, follower, bully, facilitator, organiser, editor, nurturer, know-it-all, and devil’s advocate. P7 recounted how a participant tried to assume a role:

“He will argue [with] everything you say . . . He wants to be a leader, but he’s also devil’s advocate. And, I don’t even think [laughs] he’s devil’s advocate, um, with reason and thought behind it . . . and, usually I just ignore comments from him.”

This may suggest that successful role-enacting requires adequate status or recognized legitimacy.

To re-establish or mend structure, participants observed the use of “back-peddling” (rescinding statements) and apologies: “most people will understand when you say, ‘I’m sorry. Can we move on? And, in some ways, it strengthens relationships.”

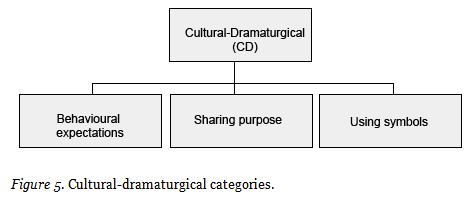

The common perception of this master of education culture is one of civility. Most described their classmates as polite, sincere, appreciative, respectful, and encouraging. As students in a Master of Education course, they felt that most classmates were working towards the same purpose—that of being student-centred professionals. However, P4 remarked that the underlying cultural expectations may subconsciously silence the voices of those with opposing views: “I think that as much as we think it’s welcoming, there’s some really subtle and not-so-subtle cues that if [you held a different viewpoint], you might be really reluctant to come forward with it.” Although memorable, personal attacks of classmates’ work or personal integrity was viewed by all participants as unusual and unacceptable. P5 even related a story in which she apologized to a victim of another student’s attack.

Cultural-online symbols such as the use of emoticons, text-messaging codes, and jargon, while mentioned, seemed less salient in the interviews. Identifiable real-life cues as to nationality or other cultural values seemed similarly muted.

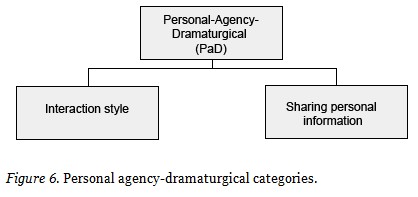

The participants revealed a range of interaction preferences. P2 and P5 indicated having regular social interactions with classmates whilst P7 and P4 preferred less interaction, leaning towards online-introversion. Meanwhile, P6 showed signs of online extroversion having few qualms about contacting others and breaking into discussions.

P5 and P4, in particular, described their preference for taking the time to carefully reflect on and shape dialogue. P4 said she only disclosed personal information that was relevant to the discussion adding that she did not actively conceal personal information, but simply chose not to reveal much. The participants acknowledged some students as “more memorable” such as those deemed boastful or who displayed rare behaviours such as personal attacks. P4 simply accepted not being a memorable, high-status participant (in her perception). Meanwhile, P2 said it did not matter what others thought of her saying, “I am who I am. And, I am that person 24 hours a day [in any context].”

The participants’ work and family backgrounds influenced the content of their messages and affected availability for interaction as well as the type of interactions experienced during crises such as illness and death in the family (i.e., expression of sympathy and support).

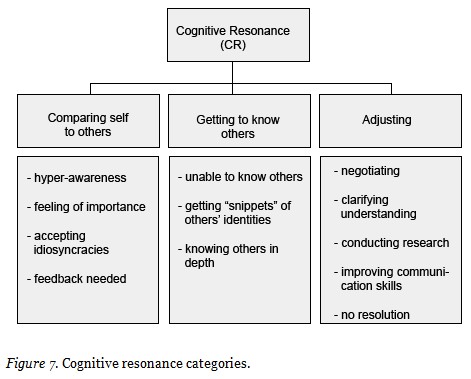

Responses to messages were used as a comparative or evaluative tool. For example, P4 noted that she was “hyper-aware” of her online interactions when she first started taking courses in the program. In particular, she constantly evaluated uncomfortable interactions reflecting, “We all need to feel important and go about it in different ways.” P7, P6, and P2 commented on the need to accept others as they are along with their idiosyncrasies. P5 felt that lack of response to forum messages was “like falling into a dead zone” and that it was “intensely uncomfortable.” P5 added, “You have to have feedback to get that sense of where you stand and a sense of grounding.”

Three participants felt that an individual’s online identity is different from one’s real-life identity—attributing lack of body language and non-verbal cues as possible causes. P5 felt:

“I’m not sure that people can really get to know each other very well in the sense of knowing the real you—unless you also have developed . . . an online friendship where you have an opportunity to talk socially outside of class and on your own time.”

Yet, they could piece together some information about the other students: P7 stated, “I think I know their goals. And, I think we’re working towards the same purpose—the same end . . . a group purpose.” P6 added, “I’ll say it’s difficult to really get to know somebody. But, you certainly get snippets, and sometimes in-depth snippets of people’s views.” And, as the number of interactions increased, P6 also noted, “it’s hard not to pick up little snippets of who they are.” At the other extreme, P6 indicated, “I, personally, find that I am able to interact on a deeper level through discussion boards.” The frequency of interaction was recognized as a significant factor online for both present and future affiliations: “The sense of community is heightened by each contact,” P5 noted. P7 also considered the possibility of future interdependency. One participant commented: “We may be colleagues down the road . . . we may need to draw upon each other for experience and advice.”

At times, the participants felt that others did not have an accurate idea of their identities or viewpoints. P2, P4 (rarely), P5, P6, and P7 resorted to private conversations to clarify interactions. P6, who claimed to openly express strong viewpoints, usually tried to provide adequate context to help clarify opinions. P6 noted that debate, “generally spurs [him/her] to go to the Internet to do a little bit more research.” P5, whose viewpoint on an issue was aggressively “shot down” by her classmates, resolved to write a research paper on the issue. There were also times when the participants could not resolve observations: “To this day, I’m still flabbergasted. And, I’m surprised often by the behaviour that occurs in group work” (P5).

The CR process stimulated the honing of strategies in accordance with cultural values and expression of power. Notably, P4 commented on how an experience in group work helped in the development of conflict-handling strategies (PD) such as negotiation: “In this last group project, we just had a really honest conversation about what our expectations were.” P4 noted becoming “more aware of preventing conflict . . . in a way that’s supportive of other people.” P4 described learning how to provide positive and constructive critiques of others’ papers. Able to reflect on feedback and previous experience, P4 altered her strategies.

All participants were able to recount narratives demonstrating variations in the enactment of the WoI strategy categories. The participants showed differences in the extent to which they attributed importance to the others’ behaviours—particularly with regard to the quantity and origin (status of the person responding) of responses to their own performances. Especially significant was lack of presence and lack of response to messages, which could be interpreted as social insignificance or exclusion.

The participants appeared to be unsure of their identities within their online learning environments, yet demonstrated attempts to identify themselves amongst others. In fact, the primary effect of interacting through the asynchronous, text-based medium of a learning management system (LMS) and social networking system was the allowance for reflecting on others’ performances and for careful scripting of their own. Whenever confronted with information that upset their concept of self or belonging, individuals would strive to regain CR. As per Walther’s (1996) research, they employed new techniques—online techniques—to re-establish epistemic fluency when self-concept thresholds were threatened. By referring to user-profiles, pictures, and previous discussion postings, they could acquire some information needed to decide whether to accept new information, clarify meaning, conduct additional research, or disregard performances.

Multiple strategies were employed in any given situation. For example, encouragement, a means of sharing one’s power (PD), may be used in consideration with cultural values (CD) or structural goals (SD). Encouraging others to persevere in the program under difficult circumstances can serve to maintain the community, elevate the status of the person encouraging, and create social alliances. Encouragement can also reflect cultural values such as mutual benefit and the creation of “safe learning environments.” Whilst aggressive message posting in terms of frequency, timing, and length may be an expression of dominance (PD), it can also be used in hopes of elevating status (SD) and being perceived as influential.

Interestingly, some dramaturgical techniques may have unintended effects. Informality of names and dialogue (SD), seemingly intended to breakdown hierarchy, can actually reinforce structure. Linguistically, formality of name use can connote various meanings (Pinker, 2007). In this study, informality conveyed intimacy suggesting previous relationships among some and excluding less intimate others. The lack of salience of national and cultural characteristics supports some of the literature suggesting that online interaction can reduce bias (Ferreday et al., 2006; Chayko, 2009); however, as we can see, other strategies may create new hierarchies.

The participants’ narrations showed variations in how the WoI strategies could be experienced (technical, power, structural, cultural, and personal agency). One’s sense of self and belonging was clearly an ongoing process involving continuous evaluation of one’s own performances contrasted to those of others. The interview data showed clear signs of conscious interpretation and strategy readjustment. This is encouraging in that it suggests that the WoI model can offer a novel lens through which to better understand how online learners use strategies to portray themselves and how they decipher the identities of others with whom they interact. Further application, testing, and refinement of the WoI model is recommended.

The WoI model may also inform the development of online learning systems. Although many social networking and learning systems provide tools for managing identities (such as profile, discussion forums, editing tools, content sharing), learners still seem to struggle to understand how others perceive them and how to understand others. As noted by one respondent, the sense of community is heightened through increased frequency of interaction. Therefore, increased opportunities for interaction may provide more opportunities for performance management and ontological re-alignment. In the words of Goodyear and Zenios (2007), “Action and identity are key” (p. 355-356).

Åkerlind, G. S. (2005). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(4), 321-334. doi:10.1080/07294360500284672

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge (p. 219). Garden City, NY: Anchor Books (Random House, Inc.).

Burr, V. (2003). Social constructionism (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Routledge.

Chayko, M. (2008). Portable communities: The dynamics of online and mobile connectedness. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Chen, S., Boucher, H., & Kraus, M. W. (2011). The relational self. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), The handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 149–175). Springer.

Christensen, N. B. (2003). Inuit in cyberspace: Embedding offline identities online. University of Copenhagen, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Collins, A., & Ferguson, W. (1993). Epistemic forms and epistemic games: Structures and strategies to guide inquiry. Educational Psychologist, 28(1), 25-42.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth, and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton. Retrieved from http://aupac.lib.athabascau.ca/record=b1014244~S0

Ferreday, D., Jones, C. R., & Hodgson, V. (2006). Dialogue, language and identity: Critical issues for networked management learning. Studies in Continuing Education, 28(3), July 2, 2009.

Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (p. 291). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Foucault, M. (1988). Technologies of the self. In L. H. Martin, H. Gutman & P. H. Hutton (Eds.), Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault (pp. 16-49). Amhurst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books.

Goodyear, P., & Zenios, M. (2007). Discussion, collaborative knowledge work and epistemic fluency. British Journal of Educational Studies, 55(4), November 25-351-368. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00383.x

Hacking, I. (2000). The social construction of what? (p. 272). Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Koole, M. (2009). The web of identity: Selfhood and belonging in online community. Unpublished manuscript.

Koole, M., & Parchoma, G. (2012). The web of identity: A model of digital identity formation in networked learning environments. In S. Warburton, & S. Hatzipanagos (Eds.), Digital identity and social media. London, UK.

Land, R., Cousin, G., & Meyer, J. H. F. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (3)*: Implications for course design and evaluation. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning diversity and inclusivity (pp. 53-64). Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

Macfayden, L. P. (2008). Constructing ethnicity and identity in the online classroom: Linguistic practices and ritual text acts. The 6th International Conference on Networked Learning, Halkidiki, Greece. 560-568.

Marton, F., & Pong, W. Y. (2005). On the unit of description in phenomenography. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(4), 335-348. doi:10.1080/07294360500284706

McInnery, J. M., & Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online learning: Social interaction and the creation of a sense of community. Educational Technology & Society, 7(3), February 27, 2010.

Norman, D. (1999). Affordance, conventions and design. Interactions, 6(3), 38-43.

Pinker, S. (2007). The stuff of thought: Language as a window into human nature. New York: Penguin Group.

Ricoeur, P. (1992). Oneself as another (Kathleen Blamey Trans.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Rovai, A. (2002). Building sense of community at a distance. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 3(1), May 20, 2009.

Schwartz, S. J., Luyckx, K., & Vignoles, V. L. (2011). Handbook of identity theory and research (S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles, Eds.) (p. 998). New York, NY: Springer.

Schwier, R. A., & Daniel, B. K. (2007). Did we become a community? Multiple methods for identifying community and its constituent elements in formal online learning environments. In N. Lambropoulos, & P. Zaphiris (Eds.), User- evaluation and online communities (pp. 29-53). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing.

Svensson, L. (1997). Theoretical foundations of phenomenography. Higher Education Research & Development, 16(2), 159-171. doi:10.1080/0729436970160204

Talja, S., Tuominen, K., & Savolainen, R. (2005). “Isms” in information science: Constructivism, collectivism and constructionism. Journal of Documentation, 61(1), November 27, 2009–79–101. Retrieved from http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/00220410510578023

Trigwell, K. (2000). A phenomenographic interview on phenomenography. In J. A. Bowden & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 62–82). Melbourne, Australia: RMIT Publishing.

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 32(1), 3-43.

© Koole