|

|

Hsin-liang Chen1 and Kevin L. Summers2

1Long Island University, United States, 2Indiana University-Indianapolis, United States

The purpose of this paper is to investigate the current video collection of an open-access video website (TED-Ed). The research questions focus on its content as evidence of development, its viewership as evidence of use, and flipping as evidence of interaction in informal learning. In late September 2013, 686 video lessons were posted on the TED-Ed website that spanned 12 academic subject categories and 60 academic subject subcategories, as labeled and sorted on the TED-Ed website itself. The findings of the analysis of the TED-Ed video collection indicate several gaps in the humanities, social science, and natural science academic areas in terms of the number of video lessons and viewership. Despite the gaps in the numbers of video lessons and the viewership across those three academic areas, the areas have very similar averages of daily flipped lessons. The future research agenda should focus on the motivation of viewers to create flipped lessons as evidence of learning in an open learning environment.

Keywords: Flipped learning; TED-Ed; informal learning; e-learning; flipped classroom

The “Flipped Learning” movement emerged in the early 21st century from K-12 schools to higher education institutions due to the availability of information technologies and free software (Bishop & Verleger, 2013). Two popular terms, “Flipped Classroom” and “Flipped Learning” have been used in the literature. EDUCAUSE defined that “[t]he flipped classroom is a pedagogical model in which the typical lecture and homework elements of a course are reversed” (2012, p. 1). However, the Flipped Learning Network (FLN, 2014, p. 1) clearly argued that those two terms are not “interchangeable.” According to FLN, “Flipped Learning” must have “Flexible Environment,” “Learning Culture,” “Intentional Content,” and “Professional Educator” (2014, p. 2). Bishop and Verleger (2013, p. 5) defined the flipped classroom “as an educational technique that consists of two parts: interactive group learning activities inside the classroom, and direct computer-based individual instruction outside the classroom.”

In addition to formal education institutions, a non-profit group named TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) launched a website, TED-Ed, where videos from TED’s recorded talks and originally produced videos are openly available. As of April 2014, TED-Ed’s open access videos are classified into 12 academic disciplines. The flipping of TED-Ed videos by teachers for use in their students’ learning activities results in the dissemination of those videos to a wider audience. Additionally, “flip” is also a reference to a nascent and evolving teaching method called “Flip Teaching” (TED-Ed, 2014).

Additionally, online information providers such as TED have offered an important research area for informal learning. Ziegler, Paulus, and Woodside (2014) pointed out that previous studies on informal learning often relied on learners’ retrospectively self-reflective reports. With the popularity of various online learning communities (e.g., YouTube, TED), researchers are able to collect data from those communities. Most up-to-date studies on flipped learning were conducted in formal learning environments (Bishop & Verleger, 2013, p. 10). There is a lack of studies on informal learning.

TED-Ed was selected as the focus of our research as the “Flipped” movement emerged and evolved as key research in education. The purpose of this paper is to investigate TED-Ed’s current video collections across all 12 disciplines as evidence of development, its viewing records as evidence of use, and its number of flipped lessons as evidence of interaction in informal learning.

Berrett (2012) reported general flipped learning development in U.S. higher education and pointed out that STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) disciplines were the major curriculum targets. Bishop and Verleger (2013) analyzed 24 studies related to flipping learning. Twenty-three of the 24 studies were in higher-education settings with one in a high school. They pointed out that most literature regarding flipped classrooms is from academically oriented news articles and online blogs and suggested that future studies should be conducted in a controlled environment to examine students’ learning outcomes objectively. Bishop and Verleger’s (2013) recommendations reflected a preferred research approach based on residential campuses. However, as the flipped learning movement is also often present in the online open environment in addition to traditional residential campuses, Bishop and Verleger’s research approach may not be suitable to online open learning environments. Additionally, Kim (2014) pointed out that a major challenge to the open online learning community is the creation of free and low-cost learning opportunities.

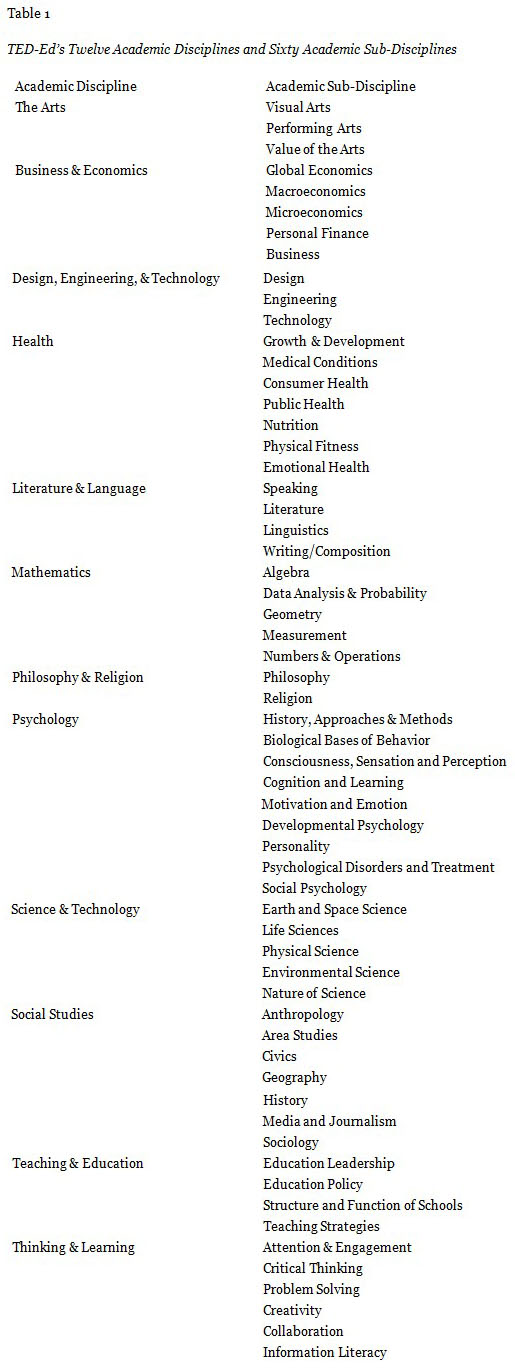

The TED-Ed website was created by TED in 2012 aiming to offer more interactive learning experiences to users when viewing a rich array of videos (DeSantis, 2012). According to the TED-Ed website: “TED-Ed’s commitment to creating lessons worth sharing is an extension of TED’s mission of spreading great ideas. Within TED-Ed’s growing library of lessons, you will find carefully curated educational videos” (TED-Ed, 2014). In late September of 2013, 686 video lessons were posted on the TED-Ed website that spanned 12 academic disciplines and 60 academic sub-disciplines (Table 1).

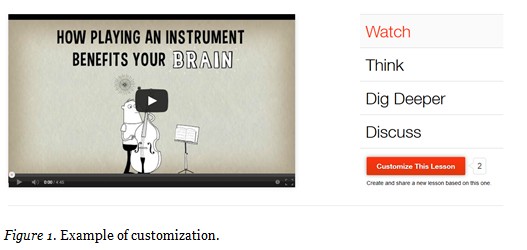

No fee or login is required to view any video lesson on the TED-Ed website. Any video lesson on the website can be customized for free, but TED-Ed does require the user to create a registration and to log in to the website before customizing a video. A customized video lesson is created by adding to or deleting from the following:

Also, users may add their own questions to the “Think” aspect of the lesson and exclude old discussions and include new discussions in the “Discuss” section of the lesson. To finish the creation of the customization, the user clicks a button titled “Finish Flip.” In this research study, the terms “customization” and “flip” are interchanged. The availability of video lessons on the TED-Ed website for free viewing and customization allows the user to engage with the video collection for informal learning and flipped learning.

The creation of the TED-Ed website is evidence of how emerging information and communication technologies (ICTs) have promoted the importance of informal learning (Cross, 2007; Downes, 2010). People must learn how to use new ICTs at work or in daily tasks because ICTs also serve as communication channels to offer instructional content. For example, Pierce and Fox (2012) asked pharmacy students to view video podcasts in a flipped topic module and those students’ performance on the final examination significantly improved compared to performance of students the previous year who completed the same module in a traditional classroom setting. Szafir and Mutlu (2013) tested college students’ attention levels in an online art history lesson and discovered that adaptively reviewing lesson content improved student recall abilities 29% over a baseline system and matched recall gains achieved by a full lesson review in less time. Galway, Corbett, Takaro, Tairyan and Frank (2014) used the pre- and post-course surveys to collect information about public health students’ learning experiences in a flipped classroom model and reported positive results regarding students’ learning experiences and deep interest in the profession.

Dabbagh and Kitsantas (2012, p. 4) proposed a framework linking formal and informal learning via social media. These levels were: (1) personal information management, (2) social interaction and collaboration, and (3) information aggregation and management. For example, instructors encourage students to use YouTube to archive personal learning materials and share their personal archives with their classmates; then the instructors can further refine the shared archives. Those archiving, sharing and refining behaviors are the evidence of formal and informal learning. However, Dabbagh and Kitsantas acknowledged that their framework needs to be supported by empirical data. Goodwin and Miller (2013) conducted a discourse analysis as a framework to study informal learning in an online hiking forum. They analyzed the threads of the forum conversations and understood how those conversations were initiated and controlled by the participants (p. 75). Based on the results of these above studies, the purpose of this project was to collect production and usage data to understand the development of videos for flipped learning. We examined the content development of TED-Ed in terms of academic subjects and its users’ online behaviors (i.e. viewing and flipping) as evidence of flipped learning in an open environment.

To answer the research questions, we collected and analyzed data from the video lesson collection posted on the TED-Ed website. Data about the video lesson collection was collected and analyzed for the following three topics: 1. academic areas/disciplines/sub-disciplines and video sources as evidence of content development; 2. viewing records as evidence of use; and 3. number of flipped lessons (i.e. customization) as evidence of interaction in informal learning. The three topics for data collection and analysis address the following three research questions:

We collected the data from TED-Ed in late September, 2013. The following describes three different data collection procedures used to address our research questions.

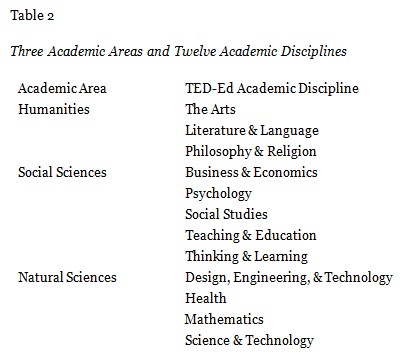

We were interested in knowing how TED-Ed develops its video lessons to promote online informal learning. In order to address our first research question, we collected data in a hierarchical structure: three major academic areas (Humanities, Natural Sciences, and Social Sciences), 12 academic disciplines, and 60 sub-disciplines (Tables 1 and 2). The three-tier structure of academic area/ discipline/sub-discipline presents a view of how TED-Ed develops its video lessons. The rationale of the structure is to see any developmental gaps in both broad and narrow academic subject areas.

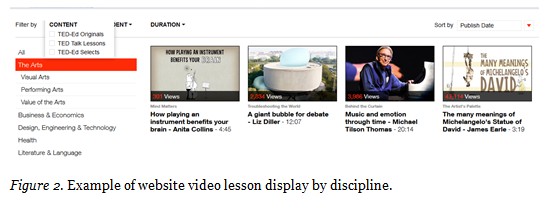

Figure 2 presents an example of the TED-Ed website’s layout for an academic discipline. In this example, the academic discipline is “The Arts,” which contains three academic sub-disciplines: 1. “Visual Arts,” 2. “Performing Arts,” and 3. “Value of the Arts.” Each of the twelve academic disciplines contains at least two sub-disciplines. Video lessons in each academic discipline or sub-discipline are displayed when selected by the user. In Figure 2, “The Arts” discipline is selected, so video lessons within that discipline are displayed on the right side of the webpage. We used a spreadsheet program to record and calculate the distribution, viewership, and flipping of video lessons in each academic area, academic discipline, and academic sub-discipline.

Additionally, we were interested in the development of TED-Ed video lessons by source type. On TED-Ed’s “Lessons” webpage, the user can sort all videos in its collection by “Content,” which are the three sources of video lessons on the website: 1. TED-Ed Originals, 2. TED Talk Lessons, and 3. TED-Ed Selects (Figure 2).

TED-Ed Original video lessons “represent collaborations between expert educators, screenwriters and animators. Each collaboration aims to capture and amplify a great lesson ideas [sic] suggested by the TED community” (TED-Ed, 2014). Also, Original video lessons “feature the words and ideas of educators brought to life by professional animators.” According to the TED-Ed website, a Select video lesson is “created by any website visitor, and involves adding questions, discussion topics and other supplementary materials to any educational video on YouTube” and that Select video lessons are “exceptional, user-created lessons that are carefully selected by volunteer teachers and TED-Ed staff.” TED-Ed reports that TED-Ed Talk Lessons are “created by TED-Ed using phenomenal TED Talks.” TED Talks are lectures given (and video recorded) on a variety of topics at events officially sponsored by the TED organization (TED, n.d.).

We recorded the total numbers of these three types of video lessons according to their academic subjects. The analysis of the types of video lessons revealed another dimension of TED-Ed’s content.

We collected data on the number of views for a video lesson by reading the display of that video’s image on the TED-Ed website (Figure 2). For example, the number of views is 301 for the first video lesson, “How playing an instrument benefits your brain.”

To obtain the publication date of a video lesson, we had to click on the video lesson’s individual link to connect to the video’s corresponding URL on YouTube’s website. Figure 3 shows an example of a video lesson published on July 22, 2014. During the data collection period, we collected each video lesson’s publication date and number of views.

We were able to collect the publication dates of TED-Ed’s Talk Lessons and TED-Ed Originals from YouTube, but not for TED-ED Selects. To obtain the correct publication dates of TED-Ed Select video lessons, we corresponded by e-mail with TED-Ed Web Support staff, who provided us with a list of publication dates for all 27 TED-Ed Select video lessons (“Sara” of TED-Ed Web Support staff, personal communication by e-mail, May 2, 2014).

In order to know how TED-Ed’s lessons have been viewed, we decided to look into each lesson’s viewership. Because the video lessons were not published simultaneously, the total number of views for each video lesson is not a meaningful comparison. We decided to calculate each video lesson’s daily average number of views. For example, to calculate the daily average of views for a video lesson published on June 3, 2013 with 345 total views as of September 25, 2013, we divided 345 (views) by 104 (days, June 3 - September 25), resulting in daily average views for this video of 3.3.

Data on the number of customizations for a TED-Ed video lesson was collected on its individual webpage by reading the number in the box that is located just to the right of the statement that reads: “Customize This Lesson” (Figure 1). We used the same procedure as viewership to calculate the daily average number of customizations for each video lesson. For example, the video lesson titled “Who Won the Space Race? – Jeff Steers” (publication date of August 14, 2013) had 38 customizations as of September 30, 2013. In this example, there were 47 days between the publication date and the date of data collection, so the daily average of customizations for this video is 0.8.

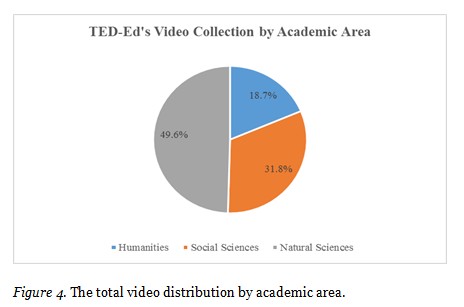

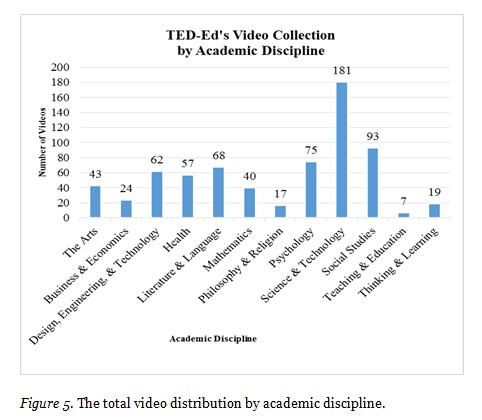

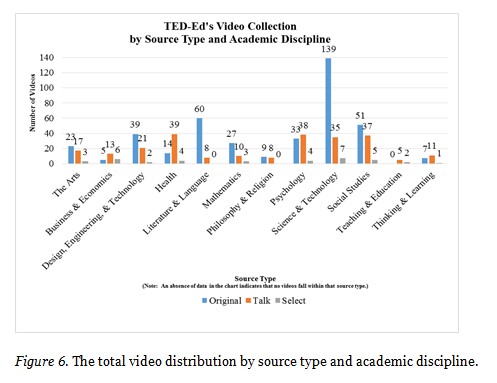

Almost 50% of video lessons fall into the natural sciences academic area, while 18.7% fall into the humanities and 31.8% into the social sciences (Figure 4). In particular, 181 of the total 686 video lessons (26.3%) fall into the academic discipline of “Science & Technology” (Figure 5). Of those 181 video lessons in “Science & Technology,” 139 are original productions by TED-Ed (Figure 6). The predominance of video lessons in the natural sciences corresponds to technology being one of TED’s three initial areas of focus.

By comparison, the four academic disciplines with the fewest number of video lessons in the collection are: 1. “Business & Economics” (24), 2. “Thinking & Learning” (19), 3. “Philosophy & Religion” (17), and 4. “Teaching & Education” (7) (Figure 5). We also observed that TED-Ed was the main creator of video lessons (i.e. “Original”) for the entire video collection (Figure 6).

There are several significant gaps within the 12 academic disciplines. For example, over 55% of video lessons in the “The Arts” discipline are in the “Visual Arts” sub-discipline; over 54% of videos in the “Business & Economics” discipline are in the “Global Economics” sub-discipline; over 69% of videos in the “Design, Engineering, & Technology” discipline are in the “Technology” sub-discipline; over 80% of videos in the “Philosophy & Religion” discipline are in the “Religion” sub-discipline; over 30% of videos in the “Psychology” discipline are in the “Motivation and Emotion” sub-discipline; over 36% of videos in the “Science & Technology” discipline are in the “Life Sciences” sub-discipline; and over 40% of videos in the “Social Studies” discipline are in the “History” sub-discipline (refer to Appendix).

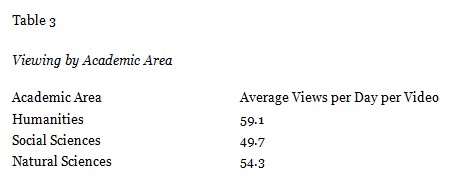

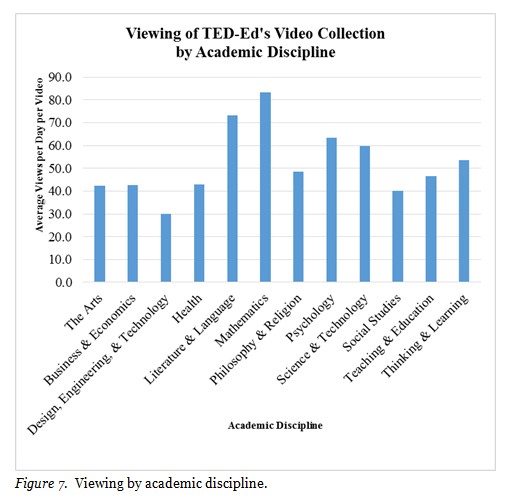

Even though the natural science area has the highest number of video lessons among the three academic areas (Figure 4), the humanities area has the highest daily average viewership per video (Table 3). “Mathematics” and “Literature & Language” are the two academic disciplines with the highest daily average viewership, followed by “Psychology” and “Science & Technology.” The discipline of “Design, Engineering, & Technology” has the lowest daily average viewership (Figure 7).

Original video lessons have higher daily average viewership among the 12 academic disciplines, except for “Design, Engineering, & Technology,” “Mathematics,” “Teaching & Education” (which has no original video lessons), and “Thinking & Learning” (Figure 8).

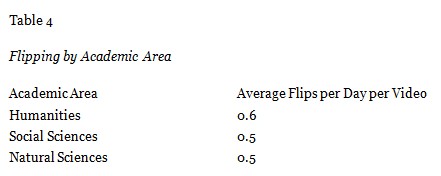

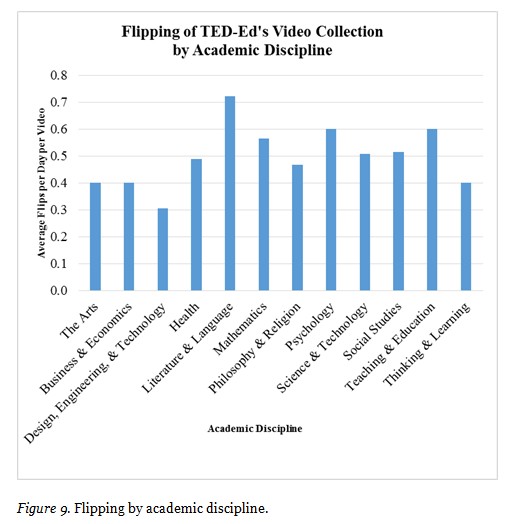

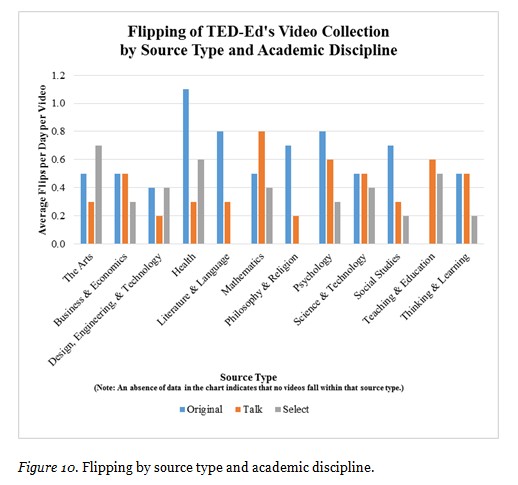

Despite the differing numbers of video lessons and daily average viewership between the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences, the three academic areas have very similar averages of daily flips per video (Table 4). The “Literature & Language” discipline has the highest average (over 0.7 flips/day), followed by “Psychology” and “Teaching & Education” (both at 0.6 flips/day) and “Mathematics” (over 0.5 flips/day) (Figure 9).

In general, viewers flip more on original lessons (Figure 10). Original video lessons in the “Health” discipline have the highest daily average of flips (1.1 flips/day), followed by “Literature & Language,” and “Psychology” (both at 0.8 flips/day) and “Social Studies” (0.7 flips/day) (Figure 10).

More video lessons for the STEM disciplines have been created by TED-Ed (i.e. “Originals”). However, lesson production gaps still exist within the STEM disciplines. For example, the “Life Sciences” academic sub-discipline constitutes more than 36% of the 181 videos in the “Science & Technology” academic discipline, which also consists of the following sub-disciplines: “Earth & Space Science” (19.3%), “Physical Science” (24.9%), “Environmental Science” (14.9%), and “Nature of Science” (4.4%) (refer to Appendix). Another example is the “Technology” sub-discipline, which constitutes 69.4% of all videos in the “Design, Engineering, & Technology” discipline (refer to Appendix). These gaps indicate that a balanced production approach is needed for the future development of video lessons on the TED-Ed website. Further research could provide data about the availability to TED-Ed of content for video lessons in various academic disciplines and sub-disciplines. Additionally, the use of “Technology” in one discipline and one sub-discipline shows that a review of the categorization of the academic disciplines is also needed.

The number of video lessons in an academic discipline does not necessarily correlate to daily average viewership. For example, the “Mathematics” discipline has the highest average daily viewership (Figure 7), but it ranked eighth among the twelve disciplines in terms of the total number of videos (Figure 5). Another example is the “Science & Technology” discipline, which contains 181 videos (the highest total number of videos for a discipline) (Figure 5), yet it ranked fourth among the twelve disciplines in daily average viewership (Figure 7). Additionally, originally produced video lessons tend to get higher daily average viewership (Figure 8), which suggests that the creation of more original lessons would increase viewership. Although varying levels of viewership by source type and academic discipline and sub-discipline provide indications of viewers’ need and desire for that content, other factors within and without the purview of TED-Ed are likely to affect viewership.

Another important finding is that the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences have very similar daily averages of flipped lessons per video (Table 3), despite the natural sciences having the highest number of videos in the collection (Figure 4). TED-Ed should promote lesson-flipping with its viewers. The even flipping of video lessons between the natural sciences, humanities, and social sciences (despite the natural sciences constituting 49.6% of the TED-Ed video collection) suggests a research topic: Do people hesitate to create flips in the natural sciences area? We also observed a higher daily average of flipped lessons in the “Health” and “Mathematics” academic disciplines. The data available in this research study do not allow for analysis of the factors that motivate users to flip TED-Ed video lessons. Beyond its academic discipline and sub-discipline, other attributes of a video lesson may affect the likelihood that it is flipped, including: topic, quality, and academic level. Understanding motivations behind the flipping of lessons is an important research topic.

There are several limitations to this study:

However, the listed limitations also provide research opportunities for future studies.

In sum, our analysis of the TED-Ed video lesson collection presents evidence for desirable changes in terms of future development at TED-Ed. Significant gaps were observed in available content across academic disciplines. As TED-Ed’s mission is to support teachers and to inspire the curiosity of learners, a more balanced offering of video content by discipline is desired. TED-Ed should review its production approach and create more video lessons for the academic disciplines with less content.

Learning assessment is also an important issue in the flipped learning movement. Policy makers, designers, and instructors have been seeking best-practice strategies to collect evidence to assess the impact of flipped learning on learners’ experiences and outcomes. Although TED-Ed is a free content provider, assessment of its impact is still important in fulfilling its mission. In this study, we focused on the content, viewership and customization behaviors as forms of assessment. Additionally, TED-Ed needs to monitor the discrepancies of viewership among the academic disciplines, even though those disciplines have different numbers of video lessons. Most importantly, the future research agenda should focus on motivating viewers to create flipped lessons as evidence of learning in an online open learning environment.

Baker, J. W. (2000). The” classroom flip”: Using web course management tools to become the guide by the side. In J. A. Chambers (Ed.), Selected Papers from the 11th International Conference on College Teaching and Learning (pp. 9-17). Jacksonville, FL: Florida Community College at Jacksonville.

Berrett, D. (2012, February 19). How ‘flipping’ the classroom can improve the traditional lecture. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved April 16, 2014, from http://chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-the-Classroom/130857/

Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. (2013). The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. In ASEE National Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved April 16, 2014, from http://faculty.up.edu/vandegri/FacDev/Papers/Research_flipped_classroom.pdf

Brame, C. J. (2013). Flipping the classroom. Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University. Retrieved April 16, 2014, from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/flipping-the-classroom/

Cross, J. (2007). Informal learning: Rediscovering the natural pathways that inspire innovation and performance. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Dabbagh, N., & Kitsantas, A. (2012). Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(1), 3-8.

DeSantis, N. (2012). New TED-Ed site turns YouTube videos into ‘Flipped’ lessons. Retrieved May 27, 2014, from http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/new-ted-ed-site-turns-youtube-videos-into-flipped-lessons/36109

Downes, S. (2010). New technology supporting informal learning. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Web Intelligence, 2(1), 27-33.

EDUCAUSE. (2012). 7 things you should know about the flipped classroom. Retrieved April 22, 2014, from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eli7081.pdf

Flipped Learning Network (FLN). (2014). The four pillars of F-L-I-P. Retrieved April 22, 2014, from http://flippedlearning.org/cms/lib07/VA01923112/Centricity/Domain/46/FLIP_handout_FNL_Web.pdf

Galway, L. P., Corbett, K. K., Takaro, T. K., Tairyan, K., & Frank, E. (2014). A novel integration of online and flipped classroom instructional models in public health higher education. BMC Medical Education, 14. Retrieved January 14, 2015, from http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1472-6920-14-181.pdf

Goodwin, B., & Miller, K. (2013). Evidence on flipped classrooms is still coming in. Educational Leadership, 70(6), 78-80.

Inside Higher Ed. (2014, April). The flipped classroom. Retrieved April 22, 2014, from http://www.insidehighered.com/content/flipped-classroom#sthash.DmvXWsSE.dpbs

Kim, C. (2014). 8 myths about MOOCs. Retrieved August 16, 2014, from https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/technology-and-learning/8-myths-about-moocs

Pierce, R., & Fox, J. (2012). Vodcasts and active-learning exercises in a “flipped classroom” model of a renal pharmacotherapy module. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 76(10). Retrieved January 14, 2015, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3530058/

Szafir, D., & Mutlu, B. (2013). ARTFul: Adaptive review technology for flipped learning. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1001-1010.

TED. (n.d.). Our organization. Retrieved May 20, 2014, from https://www.ted.com/about/our-organization

TED-Ed. (2014). About. Retrieved April 22, 2014, from http://ed.ted.com/about

Ziegler, M. F., Paulus, T., & Woodside, M. (2014). Understanding informal group learning in online communities through discourse analysis. Adult Education Quarterly, 64(1), 60-78.

The Content of TED-Ed's Video Collection by Academic Discipline and Sub-Discipline

Please see Supplementary files on the right side of the screen under the heading, Article Tools.

© Chen and Summers