Rick Cummings, Rob Phillips, Rhondda

Tilbrook, and Kate Lowe

Teaching and Learning Centre

Murdoch University

Perth, Australia

In recent years, Australian universities have been driven by a diversity of external forces, including funding cuts, massification of higher education, and changing student demographics, to reform their relationship with students and improve teaching and learning, particularly for those studying off-campus or part-time. Many universities have responded to these forces either through formal strategic plans developed top-down by executive staff or through organic developments arising from staff in a bottom-up approach. By contrast, much of Murdoch University’s response has been led by a small number of staff who have middle management responsibilities and who have championed the reform of key university functions, largely in spite of current policy or accepted practice. This paper argues that the ‘middle-out’ strategy has both a basis in change management theory and practice, and a number of strengths, including low risk, low cost, and high sustainability. Three linked examples of middle-out change management in teaching and learning at Murdoch University are described and the outcomes analyzed to demonstrate the benefits and pitfalls of this approach.

What do we know about change in universities and how it is managed? Recent research, both in the higher education sector and in the broader corporate sector, has contributed significantly to our understanding of change in higher education (Hannan and Silver, 2000; Ramsden, 1998; Scott, 2003). The drivers leading to and processes of how universities manage change (see also McConachie and Danaher; Nunan; Reid; McConachie, Danaher, Luck, and Jones, this issue) are now better understood. In the area of teaching and learning, recent change within Australian universities has been driven by a number of forces, including Australian government initiatives, resulting in a plethora of reactions from institutions. The top-down (see Inglis, this issue) and bottom-up approaches to change management have been commonly used in universities (sometimes jointly), and are well documented (Anderson, Johnson, and Milligan, 1999; Bates, 1999; Miller, 1995).

Applying a Content, Context and Process Model of change management (Pettigrew and Whipp, 1991), this paper highlights six characteristics which distinguish between these two approaches to change management. Furthermore, the process of examining Murdoch University’s change management strategy in teaching and learning against these characteristics, it was found that Murdoch University did not fit into either the top-down or bottom-up approaches to change, but rather a third approach focusing on middle management emerged, which we have termed the ‘middle-out’ approach. The paper identifies the ways in which the characteristics are manifest in three examples of change management in teaching and learning. The paper concludes by highlighting the way that the middle-out approach has influenced the strategic direction of the university.

Prior to exploring change management in teaching and learning in higher education, however, it is useful to summarize why change is such a critical topic in Australia’s higher education system.

In universities in Australia, as in most parts of the developed world, the rate and direction of change and the forces driving it are major concerns. Change is now a common process in universities, which are struggling to manage it — if they are managing it. The forces driving change are many and diverse and they are well documented. For example, “Globalisation, massification of higher education, a revolution in communications and the need for lifelong learning, leave Australian universities nowhere to hide from the winds of change” (Nelson, 2003, n.p.; see also Nunan, this issue).

Scott (2003) has summarized the influences for change created by these “winds” as:

One of the areas of greatest concern is the impact that the move to mass higher education in Australia will have on the quality of teaching and learning. The demographics of higher education in the western world have changed dramatically in the past two decades. Prior to the 1980s, higher education was for elite students and privileged five to ten per cent of the population who had the interest, motivation, and ability to learn largely on their own. However, higher education in most western developed countries is now clearly for the masses. In Australia, for example, the participation rate of 15-24 year olds rose from under 10 per cent in 1985 to over 18 per cent in 2001 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2003).

This growth has not only dramatically increased student numbers but also resulted in people with a broader range of academic ability taking part in higher education, causing concern that a proportion, perhaps a large proportion, will have greater difficulty in learning university level material, particularly when presented through traditional lecture-based teaching. This has reinforced a requirement to improve teaching and learning processes to address the needs of a larger and more diverse student population. For example, as Laurillard argues, the success of lectures

. . . depends on the lecturer knowing very well the capabilities of the students, and on the students having very similar capabilities and prior knowledge. Lectures were defensible, perhaps, in the old university systems in which students were selected through standardised entrance examinations. Open access and modular courses make it most unlikely that a class of students will be sufficiently similar in background and capabilities to make lectures work as a principal teaching method (2002, p. 93).

The Australian Government’s perception of how this will impact on the quality of teaching and learning is summarized in the following passage from the recent national review report:

Patterns of student enrollment and engagement in higher education have changed significantly. These developments have generated new expectations. Australia is actively positioning itself within an international ‘knowledge-based economy,’ which has placed new demands on higher education. The growth of the knowledge or digital economy has been accompanied by the promise of improved educational experiences through increased use of information and communication technologies, which many higher education institutions have readily adopted. The development of online learning poses both opportunities and challenges (Department of Education, Science, and Training, 2002, n.p.).

The Australian Government has been involved in efforts to improve the quality of teaching and learning in universities since 1990 through initiatives focused on project funding, including the Commonwealth Staff Development Fund (CSDF), the Committee for the Advancement of University Teaching (CAUT), the Committee for University Teaching and Staff Development (CUTSD), and the Australian Universities Teaching Committee (AUTC) (http://www.autc.gov.au/index.htm). After several years of reduced funding for teaching development, the government has recently allocated increased funding to establish the national Carrick Institute for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education.

Despite significant funding for projects aimed at improving teaching and learning, both in Australia and overseas, the success of these initiatives has been questioned (Alexander and McKenzie, 1998; Haywood, Anderson, Day, Land, Macleod, and Haywood, 1998), and there is little evidence of widespread improvements from national project funding. Johnston (1996) has argued that the project funding approach is flawed, because it relies on the ‘dissemination’ of outcomes, under the assumption that the dissemination of educational innovation occurs similarly to that of scientific innovation. She argues that this is an inappropriate model because, unlike scientific innovation, educational innovation is not a package which can be provided to staff to implement. Instead:

. . . learning to teach in new ways comes about from a more complex set of circumstances than applying new theoretical knowledge disseminated in formal modes. This complex set of circumstances comprises: the establishment of a culture in which innovative teaching is expected and rewarded, and in which teams or departments rather than isolated individuals are the unit of change; the use of strategies which involve discussion, sharing of experiences, reflection and collaborative learning; and then the support of innovation through encouragement, recognition and resources (Johnston, 1996, p. 303).

The Australian initiatives identified above did succeed, however, in focusing greater attention on the need to improve teaching and learning in Australian universities, particularly in using technology, but largely failed to bring about substantial change in the sector (Department of Education, Science, and Training, 2002). For example, in a national review of professional development of university teachers, Dearn, Fraser, and Ryan (2002) found that the previous years of funding and attention had not replaced the disparate approach to professional development in universities by a more evidence-based approach. As a result, individual universities have had to take the lead in managing change in teaching and learning.

An examination of the literature identifies a plethora of models of change management, including organizational models, soft systems models, and process flow models (see Iles and Sutherland, 2001, for a review of change management models). The Content, Context and Process Model (CCP) developed by Pettigrew and Whipp (1991) was found by the authors to be most relevant to teaching and learning in universities because it places change within a historical, cultural, economic, and political context, and it emphasizes the importance of interacting components. The main premise of this model is that successful change is a result of the interaction among the content or what of change (objectives, purpose, and goals); the process or how of change (implementation); and the organizational context of change (the internal and external environment). The model proposes the following eight interlinked factors as important in determining how successful a specific change will be:

As indicated above, the two most common approaches to achieving change in universities are top-down and bottom-up (Anderson, Johnson, and Milligan, 1999; Bates, 1999; Miller, 1995). The top-down approach seeks to achieve change through the imposition of central policies, using power-coercive strategies to effect change — that is, change is forced through strategic, financial, or industrial means (Miller, 1995). On the other hand, the bottom-up approach involves organic change arising from innovators and early adopters (Rogers, 1995), or through academics working individually or in groups, to manage the university through rational discussion and democratic decision-making processes (see also the teleological and ateleological systems discussed by McConachie, Danaher, Luck, and Jones, this issue). Longer term change management strategies often commence with one approach and evolve into the other.

With this framework in mind, the authors undertook a critical reflection on change management practices which had emerged in teaching and learning at Murdoch University over the last six years. As participant observers in this process, our observations and critical judgments were one source of data used in this study; however, other evidence was obtained from internal documents and evaluations of various initiatives in the overall change process. This analysis of change management processes at Murdoch University identified a possible third change management option, one led by middle managers, responding to demands from innovative members of the teaching staff but operating in the absence of strong and consistent leadership from either the senior executive or the academic policy-making body. This emergent model of change, termed the middle-out approach, is based both on critical analysis and on theoretical perspectives. It is the viability and usefulness of this third approach which is explored in the remainder of this paper.

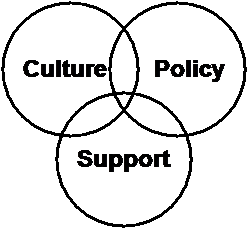

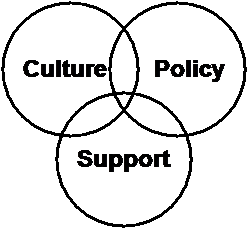

As well as the CCP model discussed earlier, an additional theoretical perspective on change management of teaching and learning in universities was provided by McNaught, Phillips, Rossiter, and Winn (2000) in their national investigation of the adoption of computer facilitated learning resources in 28 Australian universities. McNaught and her colleagues concluded that across a range of universities three factors were critical: policy, culture, and support. Policy was identified with the top-down approach, including the degree of leadership, the existence of specific institutional policies, the extent to which these policies were aligned and congruent in a particular university, and the strategic processes such as grant schemes which flowed from policies.

Culture represents the bottom-up approach, comprising factors such as the extent of collaboration within institutions, the personal motivation of innovators, and characteristics of the institution such as staff rewards, teaching and learning models, and attitudes toward innovation.

The third component, support, comprises the range of institutional infrastructure designed to assist and facilitate the change process, such as the library and information technology services, professional development of staff, student support, educational design support, and information technology literacy support for staff and students. McNaught and her colleagues (2000) represented the three components as a Venn diagram, recognizing that where change takes place there is an overlap among the three components of policy, culture and support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simplified Model of the Factors Identified As Important in the Adoption of Changes in Teaching and Learning Practice (McNaught, Phillips, Rossiter, andWinn, 2000)

McNaught and her colleagues (2000) portrayed support as a reactive role, underpinning the main players in the change game – the university administration and the teachers at the chalkface. The experiences at Murdoch University, however, indicate that the support component can play a proactive rather than a passive role, driving change outward from the middle, through operational planning and project management, solving problems, and facilitating a connection between central vision and chalkface practice. The middle-out approach is therefore closely aligned with the support component in the diagram by McNaught and her colleagues.

The three approaches to change management in universities examined in this paper are not necessarily mutually exclusive even within a single change management event. However, it is argued that the three approaches have quite different characteristics and operate in distinctive institutional environments. Furthermore, an understanding of the middle-out approach may shed some light on recent change in Australian universities and provide possible lessons for future change. Three linked examples of middle-out change management at Murdoch University are presented in the next section, followed by a comparative analysis of the top-down, bottom-up, and middle-out approaches to change management in universities.

Murdoch University has been a dual mode university since its inception in 1975, with courses of study offered in both internal (on-campus) and external (distance) modes. The external study mode was based on the systems approach of the United Kingdom Open University, with print-based study guides, and readers supplemented by audiocassette tapes. Over time, the internal and external study modes evolved separately in many units (courses), with different study materials and unit coordinators. In responding to this unsustainable structure and the forces of change identified at the beginning of this article, three linked initiatives were undertaken at Murdoch University in the period 1995-2003 which impacted significantly on change in teaching and learning. These are described below in order to inform subsequent discussion of the emergent middle-out change management strategy and its comparison to the top-down and bottom-up approaches.

In 1995, Murdoch University started to explore the potential of online teaching through substantial grant funding which was distributed across the university, in a bottom-up approach, to individuals and small groups of academic staff who used them to develop a range of innovations in online teaching and learning, some of which were supported by an online template-based system through the Teaching and Learning Centre. The initial success of this initiative, coinciding with the hype of the dot-com era, encouraged the vice-chancellor in 1997 to brand the university as a virtual university, naming it Murdoch Online, and a new, online mode of enrollment was created. Unfortunately, this top-down vision was not matched by continued funding for either central resources or unit development,or by rewards for staff who adopted its fully online approach. As a result, staff, who were initially enthusiastic, lost heart at the workload involved in developing HTML pages themselves, with little evidence of support from the centre.

Staff in the Teaching and Learning Centre recognized that the online initiative, and the benefits which could flow from it, were under threat and convinced management to provide central funding to implement the WebCT learning management system (see also Smith; McConachie, Danaher, Luck and Jones, this issue). The Centre staff also undertook a number of support activities including software improvements linking the student record system to WebCT and developing templates and staff development activities to assist staff to manage their online coursework material. This project, termed the Murdoch Online Mainstreaming project, established online teaching and learning with a strong pedagogical emphasis, as a mission-critical activity of the university, providing uninterrupted access to online course materials for students, and empowering staff to have control over their own educational material. The initiative was successful and student uptake was high (Phillips, 2002), especially among on-campus students in what is commonly called blended learning.

In 2001, the following two factors converged leading to a crisis within teaching and learning at Murdoch University:

After considerable discussion and debate involving both the university’s senior executive and Academic Council, a new approach to the design, development, and delivery of units was devised by a group of middle managers. The new approach was accepted in full by Academic Council and an implementation committee driven by middle management was established.

The flexible learning initiative reversed the previous strategy of delivering units of study to students in three modes, by proposing a flexible access approach, in which students could access the learning materials and teaching approaches in the way that best suited their needs (Phillips, Cummings, Lowe, and Jonas-Dwyer, in press). In the flexible access approach, a single set of unit materials is available to students face-to-face, in print, and online. This enabled the university to make considerable savings in teaching costs and in the production of unit materials and reduced the need for unit coordinators to produce different materials for different student cohorts. Additionally, it enabled the university to make better strategic use of its information communication and technology infrastructure such as WebCT and iLecture, a system which digitally records face-to-face lectures and makes them available to students online in near real time. A pilot study of the new approach conducted in 2002 yielded positive results for both staff and students.

By 2003, the success of the pilot persuaded the senior executive to embed the flexible learning model into the university’s new strategic plan and the implementation committee developed a plan for the conversion of all units to the new model by 2007. As at the middle of 2004, nearly 130 of a total of approximately 780 units have been converted. In addition, the university has agreed to fund the rollout of the digital recording system for lectures.

Over several years, Murdoch University identified and refined a set of graduate attributes – that is, generic academic and life skills which all students should be able to demonstrate on graduation. For these skills to be achieved, they have to be learnt at some stage of each degree program, and Academic Council required an audit to be done showing where each graduate attribute was learnt. This top-down approach was rejected by academics as meaningless managerialism.

However, the Teaching and Learning Centre, as a driver of middle-out change, recognized the opportunities of the auditing process to engage staff in reflection about the quality of their teaching practice and to facilitate wider curriculum change. Because the process of analyzing where graduate attributes were learnt was complex, a Web-based Graduate Attributes Mapping Program (GAMP) was developed (Lowe and Marshall, 2004) to simplify the mapping of graduate attributes to units of study and degree programs. On the completion of the mapping process, GAMP provides graphical and textual reports which clearly show where the graduate attributes are embedded in learning objectives, content topics, learning activities, and assessment. This information can then be aggregated across all the units in a specific degree program. At a glance, it is possible to see where attributes are addressed and whether there are significant gaps which need to be addressed.

The mapping process enabled educational designers in the Teaching and Learning Centre to encourage academics to reflect on their curriculum and to engage with them in improving it. In this way, a managerial chore was converted into a productive quality improvement activity (see also Inglis, this issue), with the potential to change the nature of e-learning provision at the university.

Owing to the success of the initiatives outlined above and the appointment of a new pro-vice-chancellor (Academic) with a strong strategic vision for teaching and learning, in 2004 the university amalgamated these three learning innovations into a single integrated and university-wide approach to curriculum change, called the School Development Process (SDP). The SDP (see http://www.tlc.murdoch.edu.au/schooldev/) is a whole-school approach to enhancing teaching and learning, coordinated by the Teaching and Learning Centre and based on systematic data collection and information provision, curriculum planning, and curriculum renewal. The process brings together each school with the Teaching and Learning Centre in a range of curriculum renewal and development activities designed to improve the quality of units as well as contribute to the review which each school at Murdoch University undergoes every five years. The process works through an initial mapping of graduate attributes which creates a focus for curriculum review and is a catalyst for further teaching development. The renewal of curriculum then involves improved integration of graduate attributes, the conversion of units to the flexible model, and the use of blended approaches to learning where this is appropriate. To date, four of Murdoch University’s 15 schools have undertaken the SDP and an evaluation of the process is currently underway.

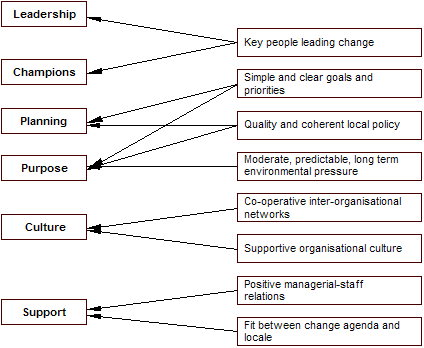

The three change management approaches — top-down, bottom-up, and middle-out — are compared in this section by applying six characteristics of change management strategies identified in this study, and which were derived from the eight success factors identified in the Context, Content, and Process model. The links between the eight CCP success factors and the six characteristics used in this study are shown in Figure 2. The relevance of each of the six characteristics to the three approaches is discussed below with reference to the literature on change management.

Figure 2. Mapping of CCP Success Factors on Characteristics of Change

Leadership is a critical element in change management in universities and can be viewed alongside management as distinct but complementary elements in the change process (Ramsden, 1998). Leadership, in Ramsden’s view, is about movement and change and has a long and rich history. It refers to individuals or small groups, is largely independent of positions, and relies on the skills of individuals, not formal power relationships. On the other hand, management is about ‘doing things right’ and is undertaken by people in formal positions responsible for planning, organizing, staffing, and budgeting. It is a relatively recent concept generated within the contemporary bureaucracy. In a similar vein, Kotter (1990) distinguishes between leaders who set direction, align people and groups, and motivate and inspire to create change, and managers who plan and budget, organize and staff, control, and solve problems in order to create order. To many staff, universities have sacrificed leadership in adopting a managerial approach to teaching and learning. In the top-down approach to change management, the leaders are senior management, using their management positions to drive change through organizational policies and restructures. In the bottom-up approach, leadership comes from individual staff who are personally inspired to make changes and to inspire others to follow their lead.

In the middle-out approach that we have observed at Murdoch University, middle managers became leaders and, through a combination of personal inspiration and policy based on emergent practice, have changed the university environment sufficiently to force both high level policy change and change in practice among teaching staff. Leadership in the middle-out approach is exhibited through problem solving and facilitation – that is, getting the job done and simplifying tasks required of those at the chalkface.

In the Murdoch University examples, the Teaching and Learning Centre provided leadership in addressing problems arising from excessive time demands on academic staff, lack of consistency in online materials, and an unsupported vision and lack of clear policy direction from senior management on the use of technology in teaching and learning. Middle managers in the Centre, the Library, and Information Technology Services, encouraged by the enthusiasm shown by a small number of early adopters but in the absence of a clear and sustainable vision from the top, provided leadership by devising a new unit model which improved flexibility for all students and permitted the university to continue to offer external enrollment, and by facilitating graduate attribute mapping within a clear pedagogical rationale.

Recent research into the nature of organizational change clearly shows the key role played by change champions (Clemmer, 2004; Scott, 2003). They are needed to provide the creative drive to overcome the bureaucratic response of “We've always done it this way,” and to push against the inertia, passive resistance, or outright opposition that impedes most changes. A good champion is passionate about her or his cause or change.

In the top-down approach, champions are generally the senior management, promoting a strong change agenda for, in their view, the good, or even the survival, of the university. In the bottom-up approach, individual staff members champion their own area of change, harnessing whatever resources they can garner individually and often using their own time to manage the change process.

In the middle-out approach, the champions are middle managers, midway between the senior staff champions in the top-down approach and the teaching staff champions in the bottom-up approach. Given their focus on problem solving and operational matters, and possessing some authority and resource to implement change, they are in a unique position to mediate between the more individualized interest of teaching staff and the broad strategic focus of senior staff. These champions may be staff in support units, such as Teaching and Learning Centers, Libraries, Quality Units, or Information Technology Services groups, who have sufficient autonomy and resources to establish change management projects within their sphere of responsibility, or where several managers are involved across a wider area of responsibility.

In the Murdoch University examples, the middle manager champions in support units took on a role separate from their normal management responsibilities to promote and implement change. They were representative on key decision-making groups, had strong links into schools, had responsibility for many of the university’s central operations (learning management systems, information systems) and supervised staff with the expertise to make sustainable changes in these systems.

Often managers of central units are joined by the dean, a head of department, or a senior academic to form a team of champions. Alexander and McKenzie (1998) found that successful projects had a head of department who supported the project (sometimes with additional funds or resources), recognized its value to the department, and was committed to its implementation. This view has been supported by a more recent international survey by Collis and van der Wende (2002).

As Iles and Sutherland (2001) point out, change can be either planned (based on deliberate and reasoned actions) or emergent (apparently spontaneous and unplanned). Planned change is characteristic of the top-down approach and generally is managed by senior management through university wide strategic and operational plans, which, although sometimes developed in consultation with staff, are seldom operationalized by them, and even less often become the new modes of day-to-day practice. This is particularly true in teaching and learning, which are very individualized practices. By contrast, the bottom-up approach is characterized by emergent change in which centralized planning is replaced by a laissez faire, organic approach, along the lines of the Chinese proverb ‘letting a thousand flowers bloom.’ Change in this strategy tends to be patchy and localized. However, as Iles and Sutherland (2001) point out, emergent change can also be based on a set of implicit assumptions about the direction in which an organization should be moving, and these assumptions may dictate the direction of change, thus “shaping the change process by ‘drift’ rather than by design” (p. 14). This approach to planning characterizes the middle-out approach, in which middle managers react pragmatically to internal and external pressures but do so in a generally consistent direction. In this case, planning is important, but it is operational or opportunistic and aimed at solving a specific problem.

In the Murdoch University examples, a clear strategic direction or management plan for teaching and learning at Murdoch University was lacking, although a number of individual staff were experimenting with innovative approaches to using technology in their teaching. In responding to the needs expressed by leading teaching staff, middle managers applied operational planning through the Murdoch Online Mainstreaming project, reallocated recurrent funds to provide staff to assist academics, and set uptake targets which were achieved. Supported by a decision of Academic Council, planning for the implementation of the flexible unit model was also largely operational, although once it was making headway it was incorporated into the university’s strategic plan in 2003. Planning in the middle-out approach is a response to emergent needs and is aimed at addressing a specific problem rather than pursuing a strategic direction.

The underlying purpose is a critical factor in change management, as it provides the drivers for the change. However, one of the key elements of this characteristic is that different stakeholders will have different views of the purpose – that is, understanding why change is needed. The diversity of views is clear when one looks at why senior managers undertake change compared with individual teaching staff. The former, representing the top-down approach, are influenced by broad university drivers such as the university’s financial situation, the prospect of new higher education student markets (see also Nunan; Reid; Inglis; Smith; McConachie, Danaher, Luck, and Jones, this issue), and the need for structural change in the university, whereas individual staff members, representing the bottom-up approach, are likely to be driven more by more specific factors such as managing increased workload, responding to student feedback, and personal interest in new technologies.

The purpose of a middle-out approach is neither policy-based nor rooted in individualism. Instead, it is problem-oriented, addressing questions such as “How can broadly based benefits be achieved?” and “How best can academics be supported in this change process?” The focus in the Murdoch University examples was on solving university-wide problems, such as ensuring an equivalent experience for students while retaining access for off-campus students in a tight financial environment, and providing a solution which would answer the strategic need to map graduate attributes through creating a tool which would have further benefits for academics wishing to enhance the quality of their units. The focus is initially on solving problems identified operationally but with the intention of creating changes in university policy and practice.

Research conducted on factors which lead to successful innovations and change has identified organizational culture as a critical factor. McNay (1995) outlines a typology of four cultures which operate in universities: collegium; bureaucracy; corporation; and enterprise. He argues that they all exist simultaneously in most universities but that the balance will vary considerably from university to university. Hannan and Silver (2000) propose the use of the concept of dominant culture to describe the balance within a particular university, emphasizing the importance of the dominant culture in universities in either enabling or inhibiting change agents and in the adoption of change.

More specifically, Alexander and McKenzie (1998) concluded, among other things, in a national study of change projects in teaching and learning in Australian universities that organizational culture was one of the factors which distinguished between successful and unsuccessful projects. Successful projects tended to be in universities where the promotion and tenure policies recognized teaching developments as a significant contribution to the university. Conversely, unsuccessful projects were usually found in institutions where these factors were missing.

Whereas there may be several cultures present in an organization, in top-down approaches to change management, the culture is usually bureaucratic, centralized, and directed, while by contrast the culture in the bottom-up approach is decentralized and individualistic, or sometimes collegial. In the middle-out approach, the institutional culture emphasizes collaboration, partnerships, negotiation, and distribution of authority. This culture is closer to the collegial culture of the bottom-up approach than to the managerial culture of the top-down approach. In fact, it could be called collegial, where collegial is interpreted as ‘moving forward together’, rather than ‘every academic can do his or her own thing’. In the Murdoch University examples, the culture was team-based and collaborative, with middle managers and their staff working closely with academic staff who needed support, and with the tacit approval of senior staff who allowed the middle managers the space and flexibility to bring about change at an operational level. The middle-out change process has been the catalyst for a broader top-down approach, the School Development Process, discussed earlier.

Finally, change takes place within an organizational setting which continues to operate while the change is occurring. The extent and type of support, in the form of public statements, policy change, financial and resource support, and organizational restructure, are critical to the change management process. Top-down approaches usually provide funding support and focus on changing the infrastructure which supports teaching and learning – for example, changes in staffing, classrooms, etc. Bottom-up approaches focus on voluntary or casual assistants to help the individual staff members to carry out their individual change projects, and initiative is supported through project funding and sometimes reward structures.

In the middle-out approach, support shares many characteristics with the top-down approach. Support is provided by centrally funded bodies, which may provide project funding, professional development, and resources (people) for project development. By contrast with the top-down approach, however, the middle-out approach provides more targeted support, focused on solving specific, university-wide problems. Support of this type also encourages early adopting staff to take a limited risk in their teaching and learning innovations. Critically, support in the middle-out approach encompasses project management (Bates, 1999), both of individual projects and of initiatives designed to support systemic change. Each of the three initiatives outlined above was formally project managed, incorporated professional development, provided production support, and benefited from efficient information systems. Developing and testing these services on a limited number of units and staff enabled them to be developed at low cost and low risk and allowed changes to be made rapidly and with little effort.

The six characteristics which distinguish approaches to change discussed above – leadership, champions, planning, purpose, institutional culture, and support – are summarized in the context of change in university teaching and learning in Table 1.

Table 1. Approaches to Innovation in Teaching and Learning

| Characteristic | Top-down | Bottom-up |

Middle-out |

| Leadership | Vision, Directives | Personal inspiration | Problem solving, Best fit, Facilitation |

| Champions | Senior management | Individual staff | Middle managers |

| Planning | Strategic | Organic Laissez faire |

Operational Opportunistic |

| Purpose | Policy | Self-interest | Problem-oriented |

| Institutional culture |

Centralized, Directed |

Decentralized, Collegial |

Collaboration, Negotiated |

Support |

Funding, Infrastructure | Voluntary assistants, One-off innovations funding | Functional and operational, including low level funding, project management, professional development |

The top-down approach is characterized by leadership from the top, with the

development of a university vision and associated strategic plans. The purpose

of the change is related to policy, and this policy is championed by senior

management. The institutional culture can be characterized as centralized and

managerial, although large institutions may necessarily have a decentralized

structure, and the motivation for change is extrinsic to those who actually

effect the change. The support for change is provided through centrally allocated

funding and the provision of the necessary infrastructure.

Similarly, in the bottom-up approach, leadership is provided by inspired and inspiring individuals seeking to solve a problem or to prevent one from arising, and thus the planning is organic or laissez faire (Bates, 1999). The purpose is the self-interest of the individuals or small groups as they struggle with the problem or issue. Generally, individuals or small group of champions, termed “Lone Rangers” by Bates (1999), arise to lead the search for the solution to the teaching and learning problem, and they work within a collegial and decentralized institutional culture. Without the formal support of the senior management, support is provided by voluntary or lowly paid assistants, characterized by Bates as the Lone Ranger’s “Tonto.”

It is important to note that the top-down and bottom-up approaches are drivers for change, as well as change management strategies. Fullan (1994) and McNaught, Phillips, Rossiter, and Winn (2000) argue that successful change usually involves both approaches, with all stakeholders able to take ownership of the innovation.

The middle-out approach has some aspects of each of the other two approaches; for example, it has access to central support, has a university-wide focus, and operates collegially. It may also take place alongside other change management approaches. It is, however, markedly differentiated, in that it is very problem-oriented and operational. As shown above, the middle-out approach developed at Murdoch University, where there was a lack either of clear direction from the top or of a consensus within the collegial agencies which drove teaching and learning policy. Within this gap, it fell to champions in middle management to identify the problem or the need for change, to develop the solutions, and to initiate the change.

We have proposed in this paper that a third approach to change management in universities, middle-out, should be considered in addition to the traditional top-down and bottom-up approaches. We have applied a set of six characteristics of change management — leadership, champions, planning, purpose, institutional culture, and support — to the three approaches and found that they do vary considerably. The examples summarized above show how Murdoch University has used this approach to considerable benefit, resulting in significant whole of university change in teaching and learning.

The middle-out approach has demonstrated a number of benefits for Murdoch University. The innovations developed through this approach have been achieved at low cost and with low risks, because the approach tends to rely on the reallocation of existing resources for the initial development and involves a small number of staff and units. As such, mistakes had limited consequences and weaknesses could be corrected quickly and at relatively low cost. This approach also provided the opportunity to conduct formative evaluation studies on the early development, again at low cost. Finally, there was the opportunity to produce evidence of successful implementation and costed models of expansion when making the case for the wider adoption of the innovation. In tight financial times and without a clear strategic mandate, these ‘runs on the board’ and evidence-based financial models have proven highly persuasive. The evidence of success has also proved to be a strong motivating factor for other staff to adopt the innovation, whether or not it is formalized official policy.

There are of course risks and disadvantages in the middle-out approach. Without senior executive or strategic support, there is a real risk that an innovation, regardless of its merit, will not have the political support required for widespread adoption. There is also a need for the middle managers to have sufficient authority or power within the university to allocate the resources necessary for pilot projects. The capacity of the innovation to be developed and implemented, albeit only in a small way, using existing resources can also be used as evidence that it doesn’t need additional resources allocated to it, so the wider implementation risks being underresourced. It is also unlikely that the broader university community will display the same readiness for change as the champions and other early adopters, and this may have implications for support and therefore costs. Finally, if the champions who develop and test the innovation do so with little, if any, additional support, they are prone to burnout from overwork and/ or lack of recognition.

The middle-out approach has been successfully used at Murdoch University in addressing problems which, for a variety of reasons, the two traditional approaches had not resolved. It developed at Murdoch University in an environment where there was a lack of clear direction from the top and where bottom-up innovation was faltering. Within this gap, it fell to middle management champions to identify the problem or the need for change, to develop the solutions, and to initiate the change. Lacking the support structure of senior management positions and sometimes acting independently of existing policy, these individuals showed leadership in moving well ahead of the rest of the university and developing new directions and ways of working for others to follow. Not only do these individuals face the difficulties of operating in a policy vacuum and sometimes contrary to current policy, but they may also face direct and explicit opposition from others in the university, particularly those managing areas likely to be affected by the change if it is adopted.

The current forces of change impacting on teaching and learning in universities create environments in which middle-out approaches to innovation and change become a legitimate option. Universities, with the individualistic nature of their academic staff, the ability to change small elements (units or courses) without disrupting the larger environment, and the need for low risk and low cost change models, are appropriate environments for this approach. As discussed earlier, for broad implementation, initiatives need to have value for, and buy-in from, both the ‘top’ and the ‘bottom’. In the examples described in this paper, the middle-out approach has clearly provided value to, and obtained buy-in from, rank and file academics, as well as convincing university senior management that proposed changes can be implemented successfully at low cost and with low risk, as is presently occurring in the School Development Process at Murdoch University.

It is unclear how widespread the middle-out approach is in Australian universities or overseas. There is anecdotal evidence that it has been tried and found useful elsewhere, but there is no systematic research to substantiate this. It would appear that the necessary conditions for it to work include:

Finally, for middle-out change management approaches to work, they eventually need to have the change adopted by the university as a whole, either formally or informally. This requires an administration open to evidence-based proposals and willing to take on and to fund partially implemented changes. At present, this is not a common phenomenon in Australian universities.

Alexander, S., and McKenzie, J. (1998). An evaluation of information technology projects for university learning. Canberra, ACT: Committee for University Teaching and Staff Development and the Department of Employment, Education, Training, and Youth Affairs. Retrieved February 17, 2005 from: http://www.autc.gov.au/in/in_pu_cu_ex.htm

Anderson, D., Johnson, R., and Milligan, B. (1999). Strategic planning in Australian universities. Retrieved July 19, 2004 from: http://www.dest.gov.au/archive/highered/eippubs/99-1/report.pdf

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2003). Education National Summary Tables: Australian social trends. Retrieved December 8, 2004 from: http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/ bd9c7737a84700f0ca256bcd008272f8!OpenDocument

Bates, A. W. (1999). Managing Technological Change: Strategies for college and university leaders. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Clemmer, J. (2004). Harnessing the energy of change champions. Retrieved November 20, 2004 from: http://www.clemmer.net/excerpts/harnes_change.shtml

Collis, B., and van der Wende, M. (2002). Models of Technology and Change in Higher Education: An international comparative survey on the current and future use of ICT in higher education. Enschede, The Netherlands: Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies, University of Twente. Retrieved July 19, 2004 from: http://www.utwente.nl/cheps/documenten/ictrapport.pdf

Department of Education, Science, and Training. (2002). Striving for Quality: Learning, teaching and scholarship. Part of the Higher Education Review Process. Retrieved July 19, 2004 from: http://www.backingaustraliasfuture.gov.au/publications/striving_for_quality/default.htm

Dearn, J., Fraser, K., and Ryan, Y. (2002). Investigation into the Provision of Professional Development for University Teaching in Australia: A discussion paper. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

Fullan, M. G. (1994). Why centralized and decentralized strategies are both essential. Retrieved 30 June, 2004 from: http://www.ed.gov/pubs/EdReformStudies/SysReforms/fullan2.html

Hannan, A., and Silver, H. (2000). Innovating in Higher Education: Teaching, learning and institutional culture. London: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Haywood, J., Anderson, C., Day, K., Land, R., Macleod, H., and Haywood, D. (1998). Use of TLTP materials in UK higher education. Edinburgh. United Kingdom: Learning Technology Research Group, University of Edinburgh. Retrieved July 19, 2004 from: http://www.flp.ed.ac.uk/LTRG/TLTP.html

Iles, V., and Sutherland, K. (2001). Organisational Change. London: National Coordinating Center for Service Delivery and Organisational Research and Development.

Johnston, S. (1996). Questioning the concept of ‘dissemination’ in the process of university teaching innovation. Teaching in Higher Education, 1(3), 295 – 304.

Kotter, J. P. (1990). A Force for Change: How leadership differs from management. New York: Free Press.

Laurillard, D. M. (2002). Rethinking University Teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies (2nd ed.) London: Routledge.

Lowe, K., and Marshall, L. (2004). Plotting Renewal: Pushing curriculum boundaries using a Web-based graduate attribute mapping tool. In R. Atkinson, C. McBeath, D. Jonas-Dwyer, and R. Phillips (Eds.) Beyond the Comfort Zone: Proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference, December 5-8 (p. 548-557). Perth, Australia: Australian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education. Retrieved December 15, 2004 from: http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/perth04/procs/lowe-k.html

McNaught, C., Phillips, R., Rossiter, D., and Winn, J. (2000). Developing a framework for a useable and useful inventory of computer-facilitated learning and support materials in Australian universities (Evaluations and Investigations Program). Canberra, ACT: Department of Employment, Training, and Youth Affairs. Retrieved July 19, 2004 from: http://www.dest.gov.au/highered/eippubs1999.htm

McNay, I. (1995). From the Collegial Academy to the Corporate Enterprise: The changing cultures of universities in the changing university? London: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Miller, H. D. R. (1995). The management of change in universities. London: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Nelson, B. (2003). Our Universities: Backing Australia’s future. Australian Government. Department of Education, Science and Training. Retrieved July19, 2004 from: http://www.backingaustraliasfuture.gov.au/ministers_message.htm

Pettigrew, A., and Whipp, R. (1991). Managing change for competitive success. Oxford, UK.: Blackwell.

Phillips, R. A. (2002). Issues Surrounding the Widespread Adoption of Learning Management Systems: An Australian case study. In A. J. Kallenberg and M. J. van de Ven (Eds.) Proceedings of the "New educational benefits of ICT in higher education" conference (p. 246-252). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus Plus.

Phillips, R. A., Cummings, R., Lowe, K., and Jonas-Dwyer, D. (in press). Rethinking Flexible Learning in a Distributed Learning Environment: A university-wide initiative. Educational Media International.

Ramsden, P. (1998). Learning to lead in higher education. London: Routledge.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Scott, G. (2003, November/ December). Effective change management in higher education. Educause Review, 64 – 80.