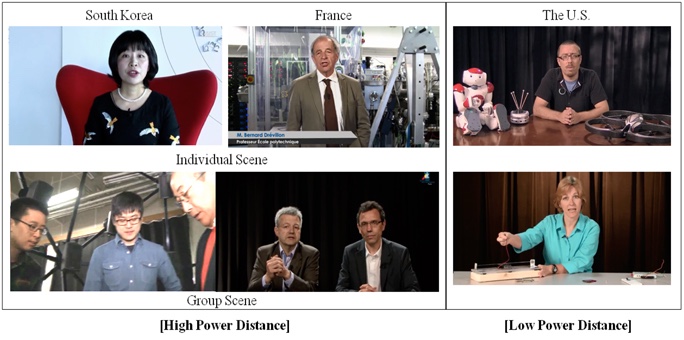

Figure 1. Example of high power distance and low power distance.

Volume 19, Number 1

Rebecca Yvonne Bayeck and Jinhee Choi

College of Education, The Pennsylvania State University

This paper discusses the influence of cultural dimensions on Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) introductory videos. The study examined the introductory videos produced by three universities on Coursera platforms using communication theory and Hofstede's cultural dimensions. The results show that introductory videos in MOOCs are influenced by the national culture of the country in which the university is based. Based on this finding, this paper raises interesting questions about the effect of these cultural elements on potential learners from different countries and cultures around the world. The paper also makes suggestions about introductory video production in MOOCs.

Keywords: MOOCs, cultural dimensions, introductory videos, potential learners

The influence of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) on educational discourse is no longer questionable (Kim, 2015). MOOCs have been presented as revolutionary and seen as an opportunity to rethink education and learning in the information age (Krause & Lowe, 2014; Waks, 2016). As a result, a growing number of institutions worldwide are developing and offering MOOCs (Margaryan, Bianco, & Littlejohn, 2015). Provided through diverse platforms (Milligan, Littlejohn, & Margaryan, 2013), MOOCs give students from around the world an opportunity to obtain free education from renowned institutions they would not have access to otherwise (Ho et al., 2014; Perna et al., 2014; Koller, Ng, Chuong, & Chen, 2013). Interestingly, the openness and free nature of MOOCs attract learners with different educational, socioeconomic, and cultural backgrounds (Baggaley, 2013; Bayeck, 2016).

Interestingly, some researchers have focused on the demographic and motivation of MOOC learners, (Bayeck, 2016; Liyanagunawardena, Lundqvist, & Williams, 2015), while others have discussed team formation and management in MOOCs (Sanz-Martinez et al., 2015), single-gender group formation in MOOCs (Bayeck, Hristova, Jablokow, & Bonafini, 2016), and the design quality of MOOCs (Margaryan, Bianco, & Littlejohn, 2015). Yet, little is known on culture and its influence on the design of MOOCs. Moreover, research shows that adjusting the design and development of e-learning environments to specific cultures ensures the success and adoption of e-learning in different cultural settings by different learners (Olaniran, Rodriguez, & Williams, 2010).

Addressing the urgent need to understand the effects of culture on online learning, Wang and Reeves (2007) explain that the heterogeneous population of learners in online education, calls for designers to find ways to accommodate learners from different cultural backgrounds. MOOCs reach a geographically and culturally diverse population (Bayeck et al., 2016; Liyanagunawardena et al., 2015), and as a new form of online education, MOOCs are cultural artifacts that are prone to be influenced by the cultural values of their developers (Dunn & Marinetti, 2007; Edmundson, 2007). As Masoumi and Lindström (2010) point out, technologies are not "passive structures" (p.80); they reflect values and beliefs in the ways they are employed. Thus, it can be assumed that culture and values are reflected in MOOCs. Understanding cultural expressions in e-learning environments becomes therefore critical because culture is the filter through which learners process and make meaning of information (Masoumi & Lindström, 2010; Olaniran et al., 2010). In addition, research investigating cultural aspects of e-learning settings argues for a "culture-centered design and development" for better learning outcomes and meaningful learning experiences for all learners (Olaniran et al., 2010, p. 449).

Still, to be able to design culturally-sensitive environments, one needs to examine what and how cultural aspects are embedded in current e-learning settings such as MOOCs (Masoumi & Lindström, 2010). Despite the popularity of e-learning and the consensus over the importance of culture in learning (Masoumi & Lindström, 2010), there is limited research addressing culture in e-learning settings (Olaniran, 2009; Olaniran et al., 2010), and particularly culture in MOOCs. Given the diversity of MOOC learners (Bayeck, 2016), insights into the cultural aspects of MOOCs is important to best serve learners. Indeed, literature shows that cultural factors impact learning, choice of images/icons, message structure, and interpretation in online learning environments (Olaniran et al., 2010). Communication approaches, and even the ways of structuring physical artifacts are affected by culture (Olaniran, 2009; Olaniran et al., 2010). For instance, images and icons have cultural meanings, and identifying cultural expressions in MOOCs could help make sense of the explicit and implicit messages in MOOCs, and help match the learning content to the learning needs of MOOC learners (Olaniran et al., 2010). To examine culture in MOOCs, this study intents to explore the influence of culture on introductory videos of institutions from three countries using Hofstede's (2001) cultural dimensions.

This paper focuses on introductory videos produced by one university from three countries France, the United States, and South Korea on Coursera platform. Using three of Hofstede's (2001) cultural dimensions, the following questions will be addressed in this study:

As movie trailers, we argue that Coursera's introductory videos help to promote and attract learners (Mihaescu & Vasiu, 2014). And as such, the introductory videos influence the potential learner's decision to either join or ignore the course. For this reason, we focus on the introductory videos because we assume that the cultural values of each country will be integrated in these short videos as a means to attract/interest learners.

This study draws on the work of Hoftsede (1997) who defined culture as "the collective programming of the mind" (p.4). Culture in Hofstede's (1980) view can differentiate one group from the other. His extensive research suggested that culture may be differentiated through five main (Table 1) cultural dimensions (Hofstede, 1980; Hofstede, 2001). These cultural dimensions unveil mental gap among dissimilar countries (Hofstede, 1997). The cultural dimensions were identified based on Hofstede's (1980) survey of IBM staff from 72 countries.

At the heart of Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions is the understanding that values and orientations differ from one culture to another, and these differences may affect communication, interactions, learning, and the understanding/processing of visual graphics/images or messages (Hedberg & Brown, 2002; Olaniran, 2007; Olaniran et al., 2010; Swierczek & Bechter, 2010). Literature has established a relationship between Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions and the design of e-learning environments (Hammer, Janson, & Leimeister, 2014; Olaniran et al., 2010). For example, in a comparative study of Chinese and German e-learners, Hammer et al. (2014) found that adding bright and striking colors, centrally aligning text and graphics, and including "nice scenarios" as well as "nature-related pictures" (p.115) in the learning content were critical to increase the user friendliness of the environment for Chinese learners. Whereas, German learners preferred a clean and "clearly structured design with simple pastel colors" (Hammer et al., 2014, p. 115). This indicates that graphics and images may make a difference in the online learning experience of individuals from different cultural backgrounds.

As previously stated, there is less research on culture and online learning environments (Olaniran et al., 2010). Yet, more studies on web design and Internet use explore culture and how it influences the design and use of websites by consumers (Swierczek & Bechter, 2010) through Hofstede's (1980) dimensions. Bansal and Zahedi (2006) in their study of cultural contents in website images, found that images on 136 websites of seven countries (Great Britain (UK), Sweden, Costa Rica, Yugoslavia, Mexico, USA, Japan) had strong cultural contents. Images non-verbally communicate subtle messages, and the authors argue that when the "cultural contents of web image(s) [fit] the culture of the web visitor" the impact of the website increases (Bansal & Zahedi, 2006, p. 1284). Bansal and Zahedi (2006) conclude that understanding the cultural messages hidden in website images can help design website that are more consistent with the website users' culture and the intended l message of websites. The findings of this research, which are appropriate for this study because of their focus on design, reveal that images can be misunderstood by individuals from by individuals from different cultures (Swierczek & Bechter, 2010). For this reason, this study explores culture in MOOCs through the lenses of Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions. Moreover, Hofstede's (1980) cultural dimensions have been used to enhance cross-cultural communication, and to develop culturally-sensitive web interfaces (Marcus & Gould, 2000). It is then appropriate to look at culture in MOOCs through Hofstede's (1980) dimensions not only because it they have been related to e-learning, but also because they have been widely used to identify cultural features in different virtual environments (Olaniran, 2007; Olaniran et al., 2010).

Hedberg and Brown (2002) state that communication and even visual communication is difficult in the absence of "shared meaning" (p.23). In other words, visual communication as it is the case of MOOC introductory videos, is challenging because each MOOC learner uses his/her culture to make sense of what is presented in the introductory videos. Research in visual communication also reports that images and background have different meanings or produce different messages in different cultures (Scherer, 2010). Discussing the different ways information is created in the technology-rich society (e.g., videos, television, computer, web images), Lester (2013) explains that "visual images can stimulate both intellectual and emotional responses; they are powerful tools that persuade people to buy a particular product, think a specific way, or learn from a detailed story" (p.13). Thus, introductory videos produced by institutions likely are powerful tools that can motivate learners to enroll into a specific course. Therefore, from a visual communication perspective, examining the content, images, or message of MOOC introductory videos is relevant for videos that are targeting learners around the world and from different cultures.

For the purpose of this study, three of Hofstede's five cultural dimensions, developed in the 1980 and refined in 2001, are used as the foundation for examining cultural features in MOOC introductory videos. Power distance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity are the three cultural dimensions examined in this paper.

Table 1

Summary of Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions Employed in This Study

| Dimension | Description |

| Power distance | Attitude of a culture towards inequalities. High power distance cultures accept unequal distribution of power in the society while low power distance cultures strive for equality. |

| Individualism-collectivism | Individualistic cultures focus on the interests of the individual and his/her direct family. Collectivist cultures emphasize the community and group dependency and loyalty is paramount. |

| Masculinity-femininity | Masculine cultures are driven by competition, success, and achievement. Feminine cultures value qualities of life, close relationships, and care for others. |

This small case study used purposive sampling to select the introductory videos to analyze. The researchers' cultural backgrounds and experience with French, South Korean, and American culture motivated the selection of the videos. A content analysis of the videos was conducted to explore the extent to which cultural dimensions are reflected in videos created for MOOCs. Since the existing research on culture in e-learning environments does not include videos, nor does it use content analysis, we adopted Bansal and Zahedi's (2006) approach to the study of cultural elements of website images, and were informed by content analysis in video game research (Wohn, 2011). Though Bansal and Zahedi (2006) analyzed websites and users across cultures, they developed a coding scheme we adopted to explore cultural dimensions in MOOC introductory videos (cf. Appendix A). Indeed, Bansal and Zahedi (2006) list signifiers/features of power distance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity (cf. Appendix A) that guided our content analysis as we look for specific features to address our research questions.

Three introductory videos respectively from the United States, South Korea, and France were selected to compare differences among these countries (Table 2). The three universities were ranked within the 100 world top universities in engineering and science fields in 2015 by the World University Ranking (Thomson Reuters, 2015). The ranking of these institutions provides a structural equivalence (i.e., objects that occupy the same position within a structural system) which allows for comparisons (Nowak, 1977). In addition, all these institutions focus on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), and all videos were under three minutes in length and discussed STEM related content. Our selection was also motivated by the researcher's understanding of the languages spoken or cultures in the respective countries (i.e., South Korea, France, and the United States).

Table 2

Cultural Dimensions of Selected Countries According to Hofstede's Dimensions

| Country | Power distance index (PDI) | Individualism (IDV) | Masculinity/Femininity |

| France | High | High | Femininity |

| South Korea | High | Low | Femininity |

| U.S. | Low | High | Masculinity |

The sample of three introductory videos from three institutions were coded by two female coders of differing cultural and educational backgrounds. Prior to coding the sample, the coders viewed and coded a pilot video and discussed the coding scheme in details. The videos were then coded independently, and about 33% of the sample (three videos) was used to test inter-coder reliability using Cohen Kappa. For most of the variables, the reliability reached 1.000, except for one variable related to the form of dressing variable (.876).

Our findings show that the videos produced by these institutions have strong cultural features. Using the code scheme developed by Bansal and Zahedi (2006), we identified elements of culture that align with Hofstede's (2001) description of each country. Features of high power distance (HPD) are reflected in French and Korean videos as focusing camera on one person, dressing professional attire, and posing in formal manner (Bansal & Zahedi, 2006), while the U.S. displays characteristics of low power distance (LPD) by placing the authority figure in the background, having casual attire (in one video), and lighting the artificial stage dimly.

Interestingly, all videos, as shown in Figure 1, reveal features of HPD: the focus on one individual, professional dress code, and formal pose. We assumed that the contextual element of academia, that pursue professional attire to give more credibility (Lightstone, Francis, & Kocum, 2011) have influence on the presence of HPD features. Although we could find elements of HPD in all videos, instructors from HPD countries tend to display stronger authoritative attitudes through their fixed looks, facial expressions, and gestures depicting power.

Figure 1. Example of high power distance and low power distance.

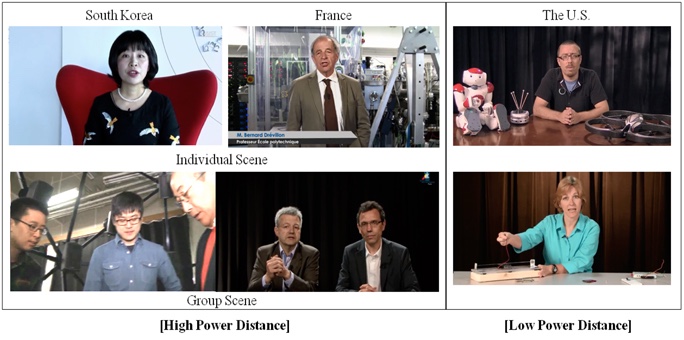

With regard to individualism and collectivism, in Figure 2, we found characteristics of individualism (IDV) in French and the U.S. videos while discovering features of collectivism (CVI) in Korean videos. Although, the American and French videos demonstrate individualism (IDV), it was shown in different ways. For example, the American videos show a single instructor, while French videos display two instructors. Yet, even when two people come up, they communicate rarely and camera focuses only one. With regards to CVI, Korean videos also go along with Hofstede's (2001) description of the country. Videos often depict group of people gazing in the same direction, and interacting together. Especially, Korean video merges these features of CVI with HPD by focusing on an instructor among students (e.g., Korean video). Non-human objects appear in multiple such as multiple leaves, fruits, logos, and funny objects.

Figure 2. Examples of individualism and collectivism.

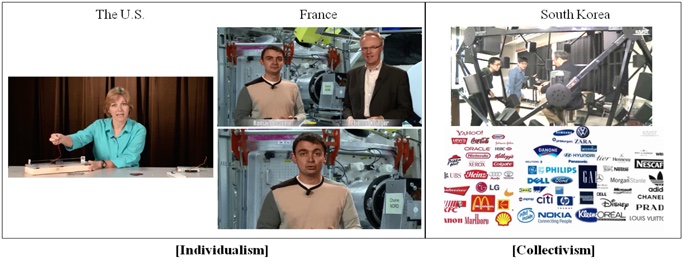

We discovered that the U.S. videos exhibit aspects of masculinity while Korean and French video show more of feminine characteristics (Figure 3). Our results demonstrate that American videos display masculinity by showing frequent non-smiling faces and disposing more black and somber color in background. On the other hand, Korean and French videos depict feminine components by smiling frequently, arranging bright colors, and placing natural environment such as flowers and natural landscape.

Figure 3. Examples of masculinity and femininity.

Overall, our analysis indicates that national cultures affect video production. One exception is found in the American videos. Although the U.S. categorized in the LPD country, its videos display features in HPD such as formal postures or dressing. We hypothesized that this may be due to the established academic culture and norm to endow credibility to students (Lightstone, Francis, & Kocum, 2011). This also shows that educational videos are certainly cultural artifacts, and MOOCs introductory videos are not an exception. MOOC providers are traditional institutions and the fact that MOOCs are free, and open to all does not mean that the content itself (e.g., introductory videos) is free from providers' culture. However, developing MOOCs that reflect a country's culture, may negatively impact the learner's experience. Building on previous research on culture and its effect on learning, we argue that a mismatch between the learners' culture and the culture reflected in MOOCs videos, can create a gap in the learner's understanding of the video material. Culture being a "mental programing" (Hofstede, 2001 p. 4), aligning the video content with the learner's culture is certainly important to ensure that the overall message of the video is understood by the MOOC learner. Although this study is limited to introductory videos, it does give insights into the effect of culture on MOOCs, particularly MOOC videos.

To meet the targeted audience, MOOC developers/providers may need to customize course contents to accommodate the needs of learners from different cultures. Our argument is based on the work of researchers such as McCombs (2000) and Olaniran et al. (2010). The challenge in online and distance learning is to design course content that supports and values diverse learners and learning content (McCombs, 2000). MOOCs as a new form of e-learning certainly face the same challenge (Diver & Martinez, 2015). Consequently, the idea of MOOCs providing education to "everybody and everywhere" (Clarke, 2013) is challenged (Jones et al., 2014) when we acknowledge that culture influences the adoption and use of technology (Olaniran et al., 2010). Thus, these introductory videos may speak and attract a specific audience; they may be meaningful for one audience, but meaningless and repulsive for another audience. MOOCs' introductory videos act as movie or game trailers; they are selling or marketing tools for the university or the course developers. As such, they should consider content, activities, gestures, and even visuals that may appeal to diverse potential learners. Understanding that marketing tools such as introductory videos can affect viewers' behaviors in ways that are consistent with the content of the message (Maibach, Roser-Renouf, & Leiserowitz, 2008), we suggest that producers of MOOC introductory videos learn and borrow from movie and game trailers to provide prospective learners with "a multimodal, multi-sensory... experience that makes them feel a part of a [the upcoming course content]" (Stapleton & Hughes, 2005, p.40).

The complexity and richness of human learning is critical in online and distance learning (McCombs, 2000). MOOCs are a growing phenomenon that makes some to believe in their potential to democratize education. However, with the effect of culture on people's understanding, interpretation of images, and content, this study problematizes MOOCs' ability to reach diverse learners. It is certainly critical to understand that: "Images... are more than mere objects; they highlight cultural phenomena and convey social meanings" (Bansal & Zahedi, 2006, p. 1285). Indeed, the interpretation and meaning of visual images and videos "are a function of the underlying ideals and beliefs of social societies" as they play a critical role in the understanding of visual message (Scherer, 2010, p. 29). Considering that MOOCs heavily rely on videos, we contend that MOOC developers "need to be aware of the role of visual communication and the impact on the learner" (Hedberg & Brown, 2002, p. 23). With Olaniran et al. (2010), we state that "in order to increase the success of [MOOCs], [videos with content and structure] must be developed to enhance the learning environment and create a meaning learning experience for all [learners] involved (p.449).

This study was limited in its scope because it only focused on the introductory videos of three institutions of higher education. The scope of the study limits the generalizability of our findings. Nevertheless, focusing on introductory videos served as a means to look into culture in MOOCs. The study sheds light on the need to explore culture in MOOC settings, and how culture can affect learners and learning in MOOCs. This study opens a discussion on the cultural underpinnings and implications of MOOCs. For instance, if MOOCs are cultural artifacts, can they be useful for learners in different cultural contexts, without taking into account the cultural backgrounds of the diverse population of learners? Ignoring the impact of culture on e-learning environments such as MOOCs can have unintentional negative consequences on learning; "It is imperative to match learning content to the needs of the learners such that this content is designed based upon a clear understanding of its cultural implications" (Olaniran et al., 2010, p. 450). We hope that this small-scale study will spark further research on the issue of culture in MOOCs.

Baggaley, J. (2013). MOOC rampant. Distance Education, 34(3), 368-378. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2013.835768

Bansal, G., & Zahedi, F. (2006). Exploring cultural contents of website images. In Proceedings of the 12 th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS). Atlanta: Association for Information Systems. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2006/170

Bayeck, R. Y. (2016). Exploratory study of MOOC learners' demographics and motivation: The case of students involved in groups. Open Praxis, 8(3), 223-233. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.8.3.282

Bayeck, R. Y., Hristova, A., Jablokow, K. W., & Bonafini, F. (2016). Exploring the relevance of single-gender group formation: What we learn from a massive open online course (MOOC). British Journal of Educational Technology. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12528

Clarke, T. (2013). The advance of the MOOCs (massive open online courses). Education + Training, 55(4/5), 403-413. doi: 10.1108/00400911311326036

Diver, P., & Martinez, I. (2015). MOOCs as a massive research laboratory: Opportunities and challenges. Distance Education, 36(1), 5-25. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2015.1019968

Dunn, P, & Marinetti, A. (2007). Effective learning strategies for cross-cultural e-learning. In A. Edmundson, (Ed.), Globalized e-learning cultural challenges (pp. 267–290). Hershey, PA: Information Science.

Edmundson, A. (2007). Globalized E-learning cultural challenges. Hersey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Hammer, N., Janson, A., & Leimeister, J. M. (2014). Does culture matter? A qualitative and comparative study on eLearning in Germany and China. In Proceedings of the 27th Bled eConference (pp. 107-124). Bled: Slovenia.

Hedberg, J. G., & Brown, I. (2002). Understanding cross-cultural meaning through visual media. Educational Media International, 39(1), 23-30. doi: 10.1080/09523980210131123

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ho, A. D., Reich, J., Nesterko, S., Seaton, D. T., Mullaney, T., Waldo, J., & Chuang, I. (2014). HarvardX and MITx: The first year of open online courses (HarvardX and MITx Working Paper No. 1).

Jones, G. M., Flamenbaum, R., Buyandelger, M., Downey, G., Starn, O., Laserna, C., & Looser, T. (2014). Anthropology in and of MOOCs. American Anthropologist, 116(4), 829-838. doi: 10.1111/aman.12143

Kim, P. (2015). Massive open online courses: The MOOC revolution. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Koller, D., Ng, A., Do, C., & Chen, Z. (2013). Retention and intention in massive open online courses: In depth. Educause Review, 48(3), 62-63.

Krause, S. D., & Lowe, C. (2014). Invasion of the MOOCS: The promises and perils of massive open online courses. Anderson, South Carolina: Parlor Press.

Lester, P. (2013). Visual communication: Images with messages. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Lightstone, K., Francis, R., & Kocum, L. (2011). University faculty style of dress and students' perception of instructor credibility. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(15), 15-22.

Liyanagunawardena, T. R., Lundqvist, K. Ø., & Williams, S. A. (2015). Who are with us: MOOC learners on a FutureLearn course? British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 557-569. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12261

Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., & Leiserowitz, A. (2008). Communication and marketing as climate change-intervention assets: A public health perspective. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), 488-500. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.016

Masoumi, D., & Lindström, B. (2014). Cultural-pedagogical norms in Iranian virtual higher education institutions. In J. Keengwe, G. Schnellert, & k. Kungu, K. (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Online Learning in Higher Education and Corporate Training (pp. 79-97). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Margaryan, A., Bianco, M., & Littlejohn, A. (2015). Instructional quality of massive open online courses (MOOCs). Computers & Education, 80, 77-83. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.005

McCombs, B. (2000, September). Assessing the role of educational technology in the teaching and learning process: A learner-centered perspective. Paper presented at the Secretary's Conference on Educational Technology: Measuring the Impacts and Shaping the Future, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/Technology/techconf/2000/mccombs_paper.html

Mihaescu, V., & Vasiu, R. (2014). Wrapping MOOCs - Analysis from a technological perspective. In Proceedings of the 10th International Scientific Conference eLearning and software for Education (pp. 261-264). Buchares, Romania.

Milligan, C., Littlejohn, A., & Margaryan, A. (2013). Patterns of engagement in connectivist MOOCs. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 149. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/vol9no2/milligan_0613.htm

Nowak, S. (1977). The strategy of cross-national survey research for the development of social theory. In A. Szalai, R. Petrella, & S. Rokkan (Eds.), Cross-national comparative survey research (pp. 3-48). Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Olaniran, B. A. (2007). Culture and communication challenges in virtual workspaces. In K. St-Amant (Ed.), Linguistic and Cultural Online Communication Issues in the Global Age (pp. 79-92). Hershey, PA: Idea Group, Inc.

Olaniran, B. A. (2009). Culture, learning styles, and web 2.0. Interactive Learning Environments, 17(4), 261-271. doi: 10.1080/10494820903195124

Olaniran, B. A., Rodriguez, N. B., & Williams, I. M. (2010). Cross-cultural challenges in web-based instruction. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal, 2(4), 448-465. Retrieved from http://www.kmel-journal.org/ojs/index.php/online-publication/article/viewFile/84/69

Perna, L. W., Ruby, A., Boruch, R. F., Wang, N., Scull, J., Ahmad, S., & Evans, C. (2014). Moving through MOOCs: Understanding the progression of users in massive open online courses. Educational Researcher, 43(9), 421-432.

Sanz-Martinez, L., Ortega-Arranz, A., Dimitriadis, Y., Munoz-Cristobal, J. A., Martinez-Mones, A., Bote-Lorenzo, M. L., & Rubia-Avi, B. (2015). Identifying factors that affect team formation and management in MOOCS. Retrieved from https://www.gsic.uva.es/uploaded_files/77623_[ITS2016WS]%20Sanz-Martinez%20et%20al.pdf

Scherer, B. N. (2010). Globalization, culture, and communication: Proposal for cultural studies integration within higher education graphic design curriculum (Master's thesis). Retrieved from Iowa State University Digital Repository. (Order No. 1476367).

Stapleton, C. B., & Hughes, C. E. (2005). Mixed reality and experiential movie trailers: Combining emotions and immersion to innovate entertainment marketing. In Proceedings of 2005 International Conference on Human-Computer Interface Advances in Modeling and Simulation (pp. 40-48). New Orleans, LA: Society for Modeling & Simulation International.

Swierczek, F. W., & Bechter, C. (2010). Cultural features of e-learning. In J. M. Spector, D. Ifenthaler, P. Isaias, Kinshuk, & D. Sampson (Eds.), Learning and instruction in the digital age (pp. 291-308). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Thomson Reuters. (2015). Subject ranking 2014-15: Engineering & technology. Internet Search. Retrieved from https://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2015/subject-ranking/engineering-and-IT#/

Waks, L. J. (2016). The evolution and evaluation of massive open online courses: MOOCs in motion. New York: Palgrave Pivot. doi: 10.1057/978-1-349-85204-8

Wang, C., & Reeves, T. C. (2007). The Meaning of Culture in Online Education: Implications for Teaching, Learning and Design. In A. Edmundson (Ed.), Globalized E-Learning Cultural Challenges (pp. 1-17). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. doi: 10.4018/978-1-59904-301-2.ch001

Wohn, D. (2011). Gender and race representation in casual games. Sex Roles, 65(3-4), 198-207. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-0007-4

| High power distance | Low power distance |

Human in images ● Person in the image is in the position of authority.

Non-Human ● Buildings have grandeur.

| Human in images ● No single person is in the position of authority.

● In a group,

Non-Human ● Single object is depicted in most images:

|

| Masculinity | Femininity |

Humans in images ● Mostly men in pictures.

● Focus:

Non-human objects ● Buildings/Structures:

|

Humans in images ● Mostly females in pictures.

● Family shown (husband-wife, children). ● Relationship shown (communication). ● Higher cases of natural, relaxed, holiday impression. ● Focus:

Non-human objects ● Buildings/Structures:

|

| Individualism | Collectivism |

Humans in images ● Single person shown.● Focus:

Non-Human Objects ● Single object is depicted in most images:

|

Humans in images ● Groups of people are depicted.

Non-Human Objects ● The objects are shown in multiple, such as:

|

The Influence of National Culture on Educational Videos: The Case of MOOCs by Rebecca Yvonne Bayeck and Jinhee Choi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.