International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning

Volume 19, Number 2

April - 2018

Mental Health in Higher Education: A Comparative Stress Risk Assessment at an Open Distance Learning University in South Africa

Jacolize Poalses and Adéle Bezuidenhout

University of South Africa

Abstract

Universities depend on committed efforts of all staff members to function effectively. However, where occupational demands outweigh occupational resources, challenging work becomes stressful, followed by an exhausted, disengaged workforce. It is unlikely that disengaged university staff will provide adequate care and service to geographically distant and psychologically isolated learners. As students rely heavily on the support of both administrative staff, as well as academic staff, to manage their learning experience, the work stress experienced by both groups deserves research attention. This study employed a comparative mixed method design, including administrative and academic staff from an Open Distance Learning university in South Africa using the Job Demands-Resources measurement instrument. Findings established from 294 university staff members elucidated staff members' experience of work stress within a mega-distance learning university in the developing world. Mindfulness about the stressors that influence university personnel can inform strategic interventions required to alleviate distress for each employment category.

Keywords: academics, administrative staff, distance learning university, job demands-resources (JDR) model, occupational stress

Introduction

It is generally reported that stress and depression are contemporary occupational diseases which adversely impact the well-being of employees to the detriment of organisational performance. Brough, Dollard, and Tuckey (2014) indicate that high levels of occupational stress experienced by academics from universities have been reported for over 20 years. The incidence of stress, anxiety, and depression furthermore seem to be increasing in most organisations, despite intensified scientific attention to this phenomenon from various disciplines. In the United Kingdom, at any one time, one worker in every six will be experiencing mental health problems related to stress (Marten, 2009). Although an academic career was traditionally seen as one offering low-stress, security, safe employment and high social standing with opportunities to do satisfying, autonomous work, universities have increasingly been exposed to the consequences of a changing environment, the changing world of work, and the concomitant, increased levels of occupational stress. Evidence in the United Kingdom (Tytherleigh, Webb, Cooper, & Ricketts, 2007), China, and Australia (Sun, Wu, & Wang, 2011) indicate that academics are specifically vulnerable to a lack of job security. Research in the higher education sector reported that academics could actually be more exposed to stress than other occupations (Catano et al., 2010). In addition, Ntshoe, Higgs, Higgs, and Wolhuter (2008) highlight the complexities of academic work, academics abandoning core teaching functions in order to give attention to miscellaneous tasks, and the distortion of roles, all of which may give rise to low staff morale.

The presence of stress at work is almost inevitable and it should also be borne in mind that it is not possible, nor desirable, to eliminate all stress. A distinction is drawn between between constructive or good stress (eustress) to which a person can easily adapt, and deconstructive or bad stress (distress), which could have discouraging consequences. However, it is maintained that a certain amount of stress is beneficial as it can be perceived as motivational (Selye, 1983; Grant, Ali, Thorsen, Dei, & Kathryn, 1995; 1995; Moorhead & Griffin, 2001). Conversely, stress only becomes problematic once the person experiencing the stress becomes convinced that the demands of the situation outweigh the ability to cope with the situation. In addition, a belief that insufficient resources (personal and otherwise) are available to deal with the demands of the situation contributes to distress.

Theoretical Perspectives

Occupational stress among university employees is a global phenomenon that does not differentiate between the socio-economic status of countries (Rocca & Kostanski, 2001; Chaudhry, 2012a; 2012b; Ablanedo-Rosas, Blevins, Gao, Teng, & White, 2011; Giorgi, 2012). O'Connor and O'Hagan (2015) elucidates a concern with the drive towards excellence in university academic staff performance as it contributes to pressure for greater accountability, bringing about higher levels of stress to succeed. The effect of such a task- and output-driven culture was observed in a study among universities from The Netherlands, Sweden, and United Kingdom, reporting an increased emphasis on performance measurement, inclusive of assessment of research, teaching, and quality (Teelken, 2011). The study refers to a verbatim comment made by an academic staff member, stating that, "university employees no longer enjoy any part of the job, apart from the vacations..." mainly due to the performance and administrative task focus that seem to distract from primary academic responsibilities (Teelken, 2011, p. 272). In addition, Pon and Lichy (2015) note that there is very little research carried out on the perceptions of academic staff in business and management fields on their working conditions, globally. They stress the importance of the latter, especially in a time when internationalisation is rapidly increasing.

Even though occupational stress seems to be globally present in universities, not all employees react similarly. An employee's natural disposition in dealing with adversity may largely determine the extent to which occupational stress is managed (Zhang, 2012). Symptoms of ill mental health, associated with uncontrollable stress levels include anxiety, panic attacks, absenteeism, irritability, loss of a sense of humour, constant tiredness, a disconnect with other people, mood swings, heart disease, and suppression of the immune system (Jackson & Rothmann 2006). The negative work outcomes associated with stress may thus be linked to impaired productivity, deteriorating interpersonal relationships, negative organisational culture, and a poor overall level of service delivery expected from staff in an ODL university.

According to Barkhuizen and Rothmann (2005) research findings have alluded to the fact that occupational stress has a negative impact on the physical and psychological health and wellbeing of both academic and administrative staff within universities. In addition, adding to the stress levels of both groups, numerous studies have reported the conflicting relationship between academic and administrative university employees (Pitman, 2000; Gill, 2009; Polster, 2012; Szekeres, 2011; Wallace & Merchant, 2011; Ylijoki & Ursin, 2013; Courtney, 2012; Kyvik, 2013; Lentell, 2012; Meng, Liu, & Xu, 2014). A typical us-and-them relationship is often depicted. However, this well-documented cause of conflict and organisational stress needs to be understood and managed, as universities worldwide rely on the skill and expertise of both the academic and supportive administrative role players to ultimately succeed in delivering high quality service to ODL learners.

Due to education demands and service delivery expectations, ODL academics often rely heavily on technology to remain contactable and attend to correspondence any time of day, as opposed to staff from contact universities (Schuldt & Totten, 2008). The continuous effort to keep up with information technology developments is one of the most cited causes of stress in higher education. A distinction can be made between "technophobia," where staff struggle to keep up with new technological developments and "over-identification" with technology, where technology consumes more time than what is desirable. Tagurum, Okonoda, Miner, Bello, and Tagurum (2017) use the term "technostress" to refer to the feeling of anxiety or mental pressure form overexposure and involvement with computer technology. Similarly, Jahanzeb (2010) describes the following general stressors in an online university environment, for which an ODL university is known for, in Pakistan: technological changes, job uncertainty, information overload, increased demand for productivity, fierce competition, and an ever changing and uncertain future. According to Siltaloppi, Kinnunen, & Feldt (2009), an online environment involves a universal occurrence of being available 24 hours a day by means of the Internet and mobile phone accessibility. In support of this finding, Schuldt and Totten (2008, p. 13) report higher stress levels in online educators than in contact educators, and attribute this mainly to the "24/7 phenomenon."

ODL universities face a significant problem in that an exhausted workforce may not have the personal resources to provide adequate care and superior service to distant learners, who are already experiencing isolation and need support to experience successful learning. As uncontrolled levels of stress are linked to increased absenteeism, presenteeism, and increased worker compensation claims, there are numerous negative consequences for the university and students. Nicklin, McNall, Cerasoli, Varga, and McGivney (2016) found that the ODL learners' physical isolation and lack of interpersonal interaction, not only increases the demands and expectations that learners may direct towards the lecturer, but also for other professionals and officials providing technical support. As the students' need for support from both administrative and academic staff to manage their learning experience increases, the work stress experienced by both groups is a relevant and important problem in ODL universities and demands research attention.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2018) acknowledges occupational stress as a serious problem and defined work-related stress as "the reaction people may have when presented with work demands and pressures that are not matched to their knowledge and abilities and which challenge their ability to cope" (para. 3). The WHO (2018) also advises that stress occurs in a wide range of work circumstances but is often made worse when employees feel they have little support from supervisors and colleagues and where they have little control over work or how they can cope with its demands and pressures (para. 3).

Conservation of Resources Theory

This research is grounded in the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Höbfoll, 1989), which is relevant for understanding the effect of job resources (or lack thereof) on employees. Although job demands are not necessarily negative, they may turn into job stressors when meeting those demands requires high effort from which the employee has not adequately recovered. Job resources refer to those physical, psychological, social, or organisational aspects of the job that are either/or:

- Functional in achieving work goals.

- Reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs.

- Stimulate personal growth, learning, and development.

Hence, resources are not only necessary to deal with job demands, but they also are important in their own right. This agrees on a more general level with Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Höbfoll, 2001) that states that the prime human motivation is directed towards the maintenance and accumulation of resources important in their own right. Höbfoll (2002) has additionally argued that resource gain, in turn, and in itself, has only a modest effect, but instead acquires its saliency in the context of resource loss. This implies that job resources gain their motivational potential, particularly when employees are confronted with high job demands.

Stressful organisations are characterised by high demands yet low resources, whereas organisations characterised by high demands and resources present a challenging work environment. Four kinds of stressors may be experienced, including acute, time limited stressors (e.g., dentist visit, disciplinary hearing), stressor sequence (e.g., job loss), chronic, intermittent stressors (e.g., regular performance reviews), and chronic stressors (e.g., unhealthy organisational culture). In addition, Hobföll (1989) identified four specific kinds of resources that play an important role in the stress experience of individuals, namely object resources (e.g., office space), conditions (e.g., tenure), personal orientation toward the world, and energies aiding the acquisition of other kinds of resources such as time, money, and knowledge.

Job Demands-Resources Research Instrument

The job demands-resources (JD-R) instrument was developed based on the COR theory of Höbfoll (1989), which integrates a number of occupational stress scales, and, at the same time extends these scales to reflect occupational stress more holistically (Pasca & Wagner 2011; van den Broeck, van Ruysseve ldt, Vanbelle, & De Witte, 2013). Moreover, this scale was validated for a South African context (Rothmann, Mostert, & Strydom, 2006). In a study of 201 telecom managers, Schaufeli, Bakker, and Van Rhenen (2009) found support for the JD-R model. The results of their study revealed that increases in job demands (i.e., overload, emotional demands, and work-home interference) and decreases in job resources (i.e., social support, autonomy, opportunities to learn, and feedback) predict burnout and burnout (positively) predict registered sickness duration and frequency (involuntary absence), respectively. Consequently, this scale was appropriate to use for purposes of this study.

The term job demands (JD) may include physical, social, or organisational demands of a job, requiring physical, cognitive, and emotional effort (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001). When these demands are high and employees do not get enough time to recover between meeting these high demands, the job demands turn into job stressors (Sonnentag & Zijlstra, 2006, as cited in Demerouti, Bakker, Geurts, & Taris, 2009). Furthermore, it is important to note that job demands may be quantitative in nature (e.g., workload, time pressures, due dates), demands may also be unique to the specific context and qualitative in nature (e.g., very complex, highly cognitive, ambiguous).

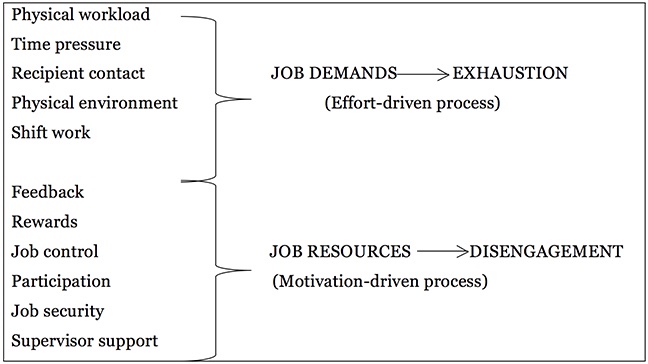

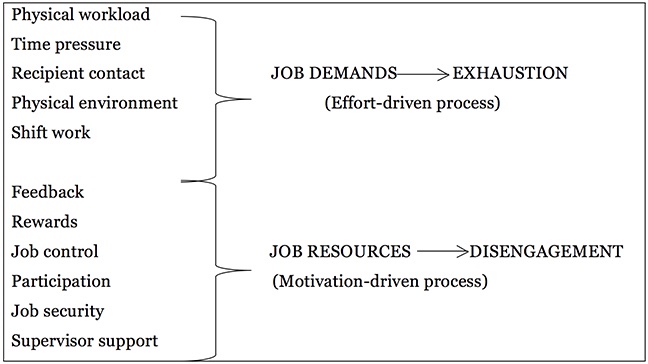

Job resources (JR) refer to physical, social, and organisational resources that support the individual in performing their jobs. These resources may reduce the strain caused by the job demands as they may reduce the costs associated with the job, help the employee to achieve their work goals, and facilitate personal growth and development (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner et al., 2001). It is evident from the above that an absence of sufficient job resources to perform the job effectively will cause an increase in the amount of stress the job incumbent experience in trying to perform the job in the best possible way. Figure 1 depicts the JD-R model of burnout.

Figure 1. JD-R Model of burnout (adapted from Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner & Shaufeli, 2001). This model illustrates the relationship between Job Demands and Job Resources on the one hand, and employees' experience of either exhaustion or disengagement on the other hand.

Thus, prolonged, ever increasing demands may exhaust the person's coping ability to such an extent that they begin to feel exhausted, cynical, and experience reduced self-efficacy, constituting the three dimensions of burnout (Maslach, Shaufeli, & Leiter, 2001).

As various groups of employees in ODL learning universities are reporting increased strain and high stress levels, this study targeted both the academic and the administrative sections of the staff complement in the largest college within a mega ODL university in South Africa. The overall purpose of this article is to explore both academic and administrative staff members' experience of work stress within a mega ODL university in the developing world.

Research Design

A post-positivistic paradigm perspective guided the primary descriptive research methodology comprising a non-experimental, cross sectional survey design. The staff database of the university's Human Resources Department was used for obtaining e-mail addresses of all staff employed within one of the five colleges within the university, namely the College of Economic and Management Sciences. This college is the largest college within the participating university, comprising of 548 permanent and temporary employed academic and administrative staff with e-mail accessibility. All staff members are involved in ODL learning exclusively, as the university does not offer any face-to-face teaching and learning. These sample elements all have Internet accessibility, which made computer-aided web surveying the most appropriate data collection method. According to this method, staff were invited via e-mail to access a survey website by clicking on a hyperlink designed for the survey. A first-round personal e-mail invitation was sent to all staff members, followed by three further weekly reminders to encourage participation among those respondents who had not responded previously to supplement the response rate. As such, the population comprised all employment categories, namely permanent and temporary fixed term employees ranging from peromnes job levels 5 (e.g., full professor) to 12 (e.g., ground level, operational). At the university the peromnes (P-level) job design system is used across all functions to refer to different hierarchical post levels of employees in permanent, full-time employment. Others are referred to as temporary staff. The total sample frame of 548 staff members were invited to participate in the survey, yielding a realised sample of 294, as such, a response rate of 54%. Table 1 presents the sample structure by P-level and employment category. The P-level titles applicable to both academic and administrative employees differ, and are also reflected.

Table 1

Sample Structure by Peromnes Job Level and Employment Category

| P-level | Academic title | Administrative title | Employee category |

| Academic | Admin |

| N |

| 5 | Full Professor | Executive Director | 25 | 2 |

| 6 | Associate Professor | Director | 16 | 2 |

| 7 | Senior Lecturer | Manager | 39 | 11 |

| 8 | Lecturer | Admin/Research Coordinator | 78 | 14 |

| 9 | Junior Lecturer | Admin Officer/ Secretary/ Research Assistant | 3 | 42 |

| 10-12 | Support Staff - Admin/Research Assistant | Support Staff - Typist/Admin Assistant | 0 | 6 |

| Temp | Supportive academic functions | Supportive administrative functions | 25 | 31 |

| | Sample (n) | 186 | 108 |

An online survey employing the Qualtrics survey software platform (Qualtrics, 2017), comprising quantitative and qualitative questions was used. The research instrument consisted of standardised questions from the JD-R instrument, customised to ensure a more personable delivery to university employees. Responses were captured on a 4-point Likert-scale, where a rating of 1 implies "never" and 4 implies "always."

Table 2

JD-R Items by Factor

| Factor | Item |

| Organisational Support | Do you receive sufficient information on the purpose of your work? |

| Do you receive sufficient information on the results of your work? |

| Do you know exactly what your direct line manager/supervisor thinks of your performance? |

| Are you kept adequately up-to-date about important issues within the university? |

| In your work, do you feel appreciated by your line manager/supervisor? |

| Do you get on well with your line manager/supervisor? |

| Do you know exactly what other people expect of you in your work? |

| Can you discuss work problems with your direct line manager/supervisor? |

| Can you count on your line manager/supervisor when you come across difficulties in your work? |

| Do you know exactly for what you are responsible? |

| Can you participate in decisions about the nature of your work? |

| Does your direct line manager/supervisor inform you about important issues within your department? |

| Growth Opportunities | Does your job offer you the possibility of independent thought and action? |

| Do you have freedom in carrying out your work activities? |

| Does your work give you the feeling that you can achieve something? |

| Do you have influence in the planning of your work activities? |

| Does your job offer you opportunities for personal growth and development? |

| Do you have enough variety in your work? |

| Does the university give you opportunities to follow training courses? |

| Overload | Do you work under time pressure? |

| Do you have to be attentive to many things at the same time? |

| Do you have too much work to do? |

| Do you have to remember many things in your work? |

| Are you confronted in your work with things that affect you personally? |

| Does your work put you in emotionally upsetting situations? |

| Do you have contact with difficult people in your work? |

| Do you have to give continuous attention to your work? |

| Job Insecurity | Do you need to be more secure that you will keep your current job in the next year? |

| Do you need to be more secure that you will still be working in one year's time? |

| Do you need to be more secure that next year you will keep the same function level as currently? |

| Relationship with colleagues | If necessary, can you ask your colleagues for help? |

| Can you count on your colleagues when you come across difficulties in your work? |

| Do you get on well with your colleagues? |

| Control | Does your job give you the opportunity to be promoted? |

| Is it clear to you whom you should address specific problems? |

| Do you have a direct influence on your department's decisions? |

| Is the decision-making process of your department clear to you? |

| Can you participate in the decision about when a piece of work must be completed? |

| Rewards | Do you think you are paid enough for the work that you do? |

| Can you live comfortably on your pay? |

| Does your job offer you the possibility to progress financially? |

| Do you think that the university pays good salaries? |

To facilitate interpretation, one satisfaction question to be rated on a 7-point Likert scale was posed, namely: "Thinking about your job at [university name], taking all things into consideration, how would you say you feel about your current situation?"

Lastly, one open, qualitative question was included to allow a deeper level of information sharing and analysis, namely: "Thinking about your job, taking all things into consideration, how do you feel about your current situation?" Table 2 depicts the JD-R items loaded onto all of the seven factors.

Research and Ethical Procedure

The study adhered to a strict research ethics Code of Conduct and did not report or avail any personal identifying information. Respondents were obliged to complete an informed consent letter, accompanying the anonymous, online survey (UNISA, 2007). A number of experts were consulted, comprising a task team of five university professors and researchers in the fields of human resources, occupational stress, industrial psychology, and research psychology, who analysed the instrument and made recommendations for improvement to ensure face validity. A pilot study with 10 respondents also provided inputs for improvement. Data obtained from the pilot study was not included in the main data set as these respondents were purposefully selected based on the fact that they would be in a position to provide constructive feedback to the questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis and Results

In terms of the quantitative analysis of the standardised JD-R survey, mean scores obtained from the 42 JD-R items rated on a 4-point Likert scale were converted to index scores to reflect a score out of 100. The methodology followed involved rank ordering the index scores and establishing quartile cut-off points based on the overall average. In presenting the findings, index scores are ranked by item. The rank ordering aids in pinpointing the most important job related stressors for both the academic and the administrative staff members. In addition an independent samples t-test analysis, also known as the two sample t-test, was performed to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference between the means in two unrelated groups (Tustin, Ligthelm, Martins, & Van Wyk, 2005), namely the manifestation of stress levels between the academic and administrative staff. Comparison of column means was performed to test for the direction of significance using the Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24. Given that the research instrument comprises 42 items, the independent samples t-test and comparison of colum means to determine the direction of significance is displayed in additional tabular format by factor only, not item, in Tables 4.1 to 4.3. Statistical significance according to the t-test by item is, however, reflected in Table 3 by asterisk (*).

Conversely, in terms of the qualitative interpretation of the participants' responses to the open-ended question, responses were analysed and categorised accordingly. Qualitative content analysis was employed, as it allows for a comprehensive and methodical analysis of the written word, in the persuit finding patterns, themes, or prejudices (Krippendorf, 2013). The qualitative analysis is useful in allowing a deeper level of understanding and interpretation of the quantitative results. An inductive coding approach was used to analyze the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Initially, the researchers read through all the text to get an understanding of the "big picture" (White & Marsh, 2006, p.37). The procedure followed was aligned to the guidelines provided by Krippendorf (2013), as well as White and Marsh (2006). This entailed developing a coding scheme through a process of close, iterative reading to identify concepts and patterns. Similar codes were combined into categories, in order to reduce the data further. Thus, a process of reading and re-reading, trying to identify important, key phrases, and unexpected ideas were followed. The researchers continued to identify codes and categories through the iterative reading process. Care was taken to ensure the codes and categories were independent, mutually exclusive, and exhaustive.

In order to improve the rigour of the research, multiple coding was employed, as both researchers analysed the same data set (Barbour, 2001). As recommended by Weber (1990), the researchers discussed and defined the meaning of codes and categories in detail, to avoid ambiguity and ensure they share the same understanding of the different codes and categories. This process helped to improve the inter-rater reliability (reproducibility) and intra-rater reliability (stability) referring to the ability of the same rater to get the same results, during another round of coding (Weber, 1990). Both intra- and inter-rater reliability is necessary to ensure the trustworthiness.

Finally the analysed data was related back to the phenomenon under study, and inferences were drawn (Krippendorf, 2013). The inferences were aimed at the overall purpose of this article, namely to explore both academic and administrative staff members' experience of work stress within a mega ODL learning university in the developing world.

Quantitative analysis is presented by employment category and either item and/or factor. The JD-R occupational stress and risk ranking index scores of the work-related items are reflected in more detail in Table 3. The bold entry items reflect the averages for the seven underlying factors.

Table 3

Occupational Stress and Risk Ranking by Item

| JD-R item | Employment category |

| Academic | Admin | Gap |

| Does your job give you the opportunity to be promoted? | 49.1 | *23.8 | 25.3 |

| Does your job offer you opportunities for personal growth and development? | 65.3 | *48.3 | 17.0 |

| Does the university give you opportunities to follow training courses? | 78.2 | *61.4 | 16.8 |

| Do you need to be more secure that you will keep your current job in the next year? | *47.6 | 63.2 | 15.6 |

| Are you confronted in your work with things that affect you personally? | 50.9 | *65.8 | 14.9 |

| Can you participate in the decision about when a piece of work must be completed? | *41.6 | 56.4 | 14.8 |

| Job Insecurity | * 46.3 | 60.5 | 14.2 |

| Do you need to be more secure that you will still be working in one year's time? | *50.0 | 64.1 | 14.1 |

| Do you think that the university pay good salaries? | *48.7 | 62.3 | 13.6 |

| Does your work give you the feeling that you can achieve something? | 64.7 | *51.5 | 13.2 |

| Do you work under time pressure? | *32.9 | 46.0 | 13.1 |

| Do you need to be more secure that next year you will keep the same function level as currently? | *45.4 | 57.5 | 12.1 |

| Do you have to be attentive to many things at the same time? | 26.3 | *36.4 | 10.1 |

| Do you have enough variety in your work? | 65.0 | *55.9 | 9.1 |

| Is it clear to you whom you should address for specific problems? | *59.7 | 68.6 | 8.9 |

| Does your work put you in emotionally upsetting situations? | 61.4 | *69.9 | 8.5 |

| Growth Opportunities | 62.1 | * 54.4 | 7.7 |

| Do you know exactly for what you are responsible? | *78.0 | 85.7 | 7.7 |

| Do you know exactly what your direct line manager/supervisor thinks of your performance? | 55.5 | 63.0 | 7.5 |

| In your work, do you feel appreciated by your line manager/supervisor? | 60.0 | 67.3 | 7.3 |

| Do you know exactly what other people expect of you in your work? | *65.7 | 72.7 | 7.0 |

| Workload | * 36.7 | 43.0 | 6.3 |

| Do you get on well with your line manager/supervisor? | 74.1 | 80.3 | 6.2 |

| Can you participate in decisions about the nature of your work? | 54.6 | 60.7 | 6.1 |

| Do you have a direct influence on your Department's decisions? | 29.6 | 35.1 | 5.5 |

| Are you kept adequately up-to-date about important issues within the university? | 62.0 | 56.8 | 5.2 |

| Do you get on well with your colleagues? | 76.8 | 81.8 | 5.0 |

| Organisational Support | 64.6 | 69.6 | 5.0 |

| Does your job offer you the possibility of independent thought and action? | 63.3 | 58.6 | 4.7 |

| Relationships | 60.5 | 65.1 | 4.6 |

| Do you have contact with difficult people in your work? | 52.0 | 48.0 | 4.0 |

| Do you have too much work to do? | 32.2 | 36.1 | 3.9 |

| Do you receive sufficient information on the purpose of your work? | 60.0 | 63.9 | 3.9 |

| Rewards | 42.7 | 46.1 | 3.4 |

| Can you count on your line manager/supervisor when you come across difficulties in your work? | 67.8 | 71.0 | 3.2 |

| Control | 53.8 | 56.9 | 3.1 |

| Does your job offer you the possibility to progress financially? | 41.1 | 38.2 | 2.9 |

| Do you have to give continuous attention to your work? | 16.3 | 19.1 | 2.8 |

| Do you receive sufficient information on the results of your work? | 55.1 | 57.7 | 2.6 |

| If necessary, can you ask your colleagues for help? | 64.4 | 62.0 | 2.4 |

| Do you think you are paid enough for the work that you do? | 39.8 | 42.2 | 2.4 |

| Can you live comfortably on your pay? | 43.0 | 40.8 | 2.2 |

| Do you have to remember many things in your work? | 20.4 | 22.2 | 1.8 |

| Do you have freedom in carrying out your work activities? | 61.5 | 60.2 | 1.3 |

| Can you discuss work problems with your direct line manager/supervisor? | 66.5 | 67.3 | 0.8 |

| Do you have influence in the planning of your work activities? | 53.0 | 52.3 | 0.7 |

| Can you count on your colleagues when you come across difficulties in your work? | 59.5 | 60.1 | 0.6 |

| Does your direct line manager/supervisor inform you about important issues within your department? | 65.1 | 64.5 | 0.6 |

| Is the decision-making process of your Department clear to you? | 53.4 | 54.0 | 0.6 |

*p ≤ 0.05

Whilst not highly significant, administrative and academic staff at the ODL university are in agreement about certain occupational stressors, namely time pressures, the need to be attentive to many things simultaneously, workload, being excluded from departmental decisions, rewards and remuneration, and having to give continuous attention to work. The findings show that certain causes of stress within the university college are generic and effects the entire staff complement. However, it is evident from Table 3 that administrative and academic staff show statistical significant differences to occupational stressors on 17 of the 42 JD-R items, and the direction of significance revealed that administrative staff experience stress due to mainly limited promotional and personal growth and development opportunities, such as not having enough or any opportunities to follow training courses. These individuals often feel personally affected by things that happen at work and are less convinced that they can attain success. Administrative staff furthermore experience significantly higher levels of stress from having to be attentive to many things at the same time, yet also report significantly high stress due to not having sufficient variety in their work. Therefore, it seems that although there is a high expectation from them to complete many tasks, these staff are of the opinion that their tasks are often mundane in nature, not providing sufficient intellectual stimulation.

Contrary, academic staff experience significantly higher stress due to mainly feelings of job insecurity, poor renumeration, high workload, time pressure, not having role clarity on what is exected from them, and not knowing whom can be asked for help if needed. These individuals feel excluded from decisions about work that affect them. Tests for statistical significant differences are displayed in Tables 4.1 to 4.3.

Table 4.1

Occupational Stress and Risk Indices by Factor

| Factor | Admin | Academic |

| Index |

| Overload | 42.97 | *36.67 |

| Growth opportunities | *54.44 | 62.07 |

| Relationships | 65.05 | 60.46 |

| Organisational support | 69.61 | 64.58 |

| Control | 56.93 | 53.80 |

| Job insecurity | 60.50 | *46.33 |

| Rewards | 46.09 | 42.68 |

| Average | 59.38 | 58.39 |

*p ≤ 0.05

Results in Table 4.1 show that academic and administrative staff members differ significantly with regard to overload, growth opportunities, and job insecurity. Whilst staff from both employee categories experience concerning high levels of overload, the academic staff members reportedly carry a heavier burden and experience higher levels of job insecurity. In contrast, administrative staff members reported higher stress levels as a consequence of insufficient growth opportunities. The statistical significance was performed using an independent samples t-test, of which the results of the two-tailed t-test is evident in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2

Independent Samples T-Test by Factor

| Factor | t | Sig. (2-tailed) |

| Overload | *2.99 | 0.003 |

| Growth opportunities | *-2.76 | 0.006 |

| Relationships | 1.78 | 0.076 |

| Organisational support | 1.92 | 0.056 |

| Control | 1.10 | 0.270 |

| Job insecurity | *3.45 | 0.001 |

| Rewards | 1.01 | 0.316 |

| Average | 0.61 | 0.544 |

*p ≤ 0.05

Table 4.2 displays the results of the two-tailed t-test to determine statistical significance by factor. The statistical tests in Tables 4.2 and 4.3 confirm that academic staff experience significantly higher levels of occupation stress related to work overload and job insecurity, whereas administrative staff experience significantly higher levels of occupational stress related to growth opportunities. The statistical significance was analysed at a 95% confidence interval of the difference.

In order to clarify the direction of the significance, the Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons in Table 4.3 is used to indicate whether administrative or academic staff experience higher levels of occupational stress on the identified factors.

Table 4.3

Bonferroni Correction for Pairwise Comparisons

| Factor | Admin (A) | Academic (B) |

| Overload | B(.003) | |

| Growth opportunities | | A(.006) |

| Relationships | | |

| Organisational support | | |

| Control | | |

| Job insecurity | B(.001) | |

| Rewards | | |

| Average | | |

*p ≤ 0.05

The direction of the significance confirmed by Table 4.3 indicates that Academic staff reported significantly higher occupational stress levels due to perceived aspects related to work overload and job insecurity. Conversely, Administrative staff reported statistically higher occupational stress levels due to perceived aspects related to growth opportunities.

Findings and Discussion From Qualitative Analysis

A few comments reiterating the "us-and-them" sentiment between administrative and academic staff can be seen in some of the following verbatim excerpts, mostly related to support, or the lack thereof. In addition, some comments illustrate generic occupational stressors for administrative and academic staff respectively. The JD-R factor best aligned to the sentiment is given in brackets.

Stressors for academic staff. A sense of being overwhelmed, helpless, and not having personal control emerged from the ODL educators. It seemed that increasing governance demands and the impact on workload has been significant. For example, academics, used to the academic freedom to decide the standard of an exam paper, find it stifling to adjust to governance demands. The possibility of litigation gave birth to numerous "quality assurance templates" to be completed. Various rounds of quality assurance by secondary lecturers, quality assurers, chairs of departments, and even faculty management. Similarly the ODL educators are required to check and re-check fellow academics' material, assignments and papers. This fuels the impression of an extremely high administrative burden.

Evidence of the frustration caused, include comments such as "admin tasks are gradually being transferred to the academics." Due to the fear of security breaches, academics within this college are expected to capture exam marks on a specific ICT system. Previously this task was allocated to administrative staff. Although it may be a minor addition, it entails additional ICT training, typing skills, and competencies that academics may not have. Class sizes of thousands of students and checking marks for correctness add a significant time investment to an overburdened staff compliment. Academics typically feel robbed of research time and this may lead to more stress and resistance. "My work now is administrative because I never get time to immerse myself in my academic passions" (lack of organisational support / loss of personal control / work overload). Academics expressed a lack of personal control such as to "(r)esist the extreme intrusion and prescriptiveness of administration and educational philosophers." Many of the ODL educators' reflections allude to feelings of being overworked and over extended, for example expressing a need for "assistance with workload," "communicate due dates of all activities and submissions at the beginning of the year to all members of staff," "less relentless mind numbing never ending deadlines," "get rid of the ever escalating administrative burden imposed on academics," "extended time frame for completion of tasks," "work-life balance - require flexible working hours to manage workload," direct requests to "hire more staff," and a need for "user friendly operational systems." When interpreted in terms of the JD-R theoretical framework a pattern emerges from the verbatim evidence showing a lack of organisational support, loss of personal control, and work overload.

Stressors for administrative staff. Tipping the scale towards the other side, administrative staff expressed a need for "clear job descriptions," "task clarity," and require more "goal directedness" (organisational support). Furthermore, from some of the administrative staff's statements it seems as if they often feel misused, as illustrated by quotes such as "draft and construct clear job descriptions for administrative staff based on the departmental expectations" (operations, objectives, support) and "not to put admin only when there are already existing problems" (organisational support). In addition administrative staff members expressed a need for "improved teamwork" and "bridging the gap between admin staff and academics" (relationships). The verbatim evidence shows that although the main administrative stressors may be different from academic stressors, these staff members too suffer from continuous feelings of uncontrolled stress and anxiety.

Finding solutions. Both employment categories were given the opportunity to express core changes necessary to alleviate occupational stress levels. Sentiments relating directly to academic versus administrative staff were expressed mostly by academic staff members. Aligned to the JD-R model, experiencing a sense of a lack of support is indicative of a perceived lack of resources. As such, these academics mostly feel that they are not sufficiently equipped and supported by administrative staff in order to meet their job expectations. Evidence for this sentiment is presented in statements such as: "use people according to their strength," "with the way we are going now - fire all the academics and appoint admin people in their place," and "a supportive administration - currently, the tail wags the dog" (Organisational support).

Given the opportunity to reflect on occupational matters requiring improvement, these staff members expressed the pervasive need for reduced levels of workload, a fair and manageable distribution of workload, a need for improved institutional and administrative support, and efficient systems. Administrative staff expressed the need to be more involved and engaged in teamwork, improved task clarity, and goal directedness. The feeling of being overburdened was reiterated by academics' comments related to the need to not be overworked, academics needing administrative tasks to be assigned to administrative colleagues, and expressing a need for realistic timeframes to attend to job demands. Overall, academics seemed of the opinion that they are unable to dedicate the required time and attention to academic responsibilities due to increased administrative, regulatory, and compliance responsibilities. Table 5 presents a summary of the major qualitative findings.

Table 5

A Summary of the Major Qualitative Findings

| Major sources of stress |

| Generic to both academic and administrative staff | Specific to academic staff | Specific to administrative staff |

| Time pressures | Feelings of job insecurity | Limited promotional and personal growth and development opportunities |

| Being attentive to many things simultaneously | Poor remuneration | Feelings of being personally affected by things that happen at work |

| Workload/ overload | High workload and time pressure | Doubt whether they can attain success |

| Being excluded from departmental decision-making | Feel excluded from decisions about work that affect them | Not having sufficient variety in allocated work |

| Rewards and remuneration | Role clarity | |

| Having to give continuous attention to work | | |

Discussion and Recommendations

The empirical evidence reported on in this article helps to foster a deep psychological understanding of the job-demands that face staff members within this university. Thus, the findings create mindfulness about the stressors, in order to inform the strategic decisions and interventions required from policy makers, to alleviate some of the distress experienced by all the people affected in the university.

Due to the pervasiveness of occupational stress and stressors, no one is immune to the effect on their mental health and well-being, regardless of job title, daily tasks, or work setting. A heavy workload accompanied by unfeasible additional administrative duties and limited organisational support have been identified as predominant contributors that place these university staff members at risk of experiencing negative occupational stress. Although organisational support personnel and systems are in place, these staff members and systems are perceived as either lacking sufficient capacity or being incompetent in dealing with requirements.

Academic staff members experience exceptional levels of occupational stress due to a wide array of time consuming job requirements against which performance is measured, resulting in limited time for research when having to weigh immediate requirements. In addition, bureaucracy and "red tape" prevents staff members from taking innovative and independent action.

The study results' main contribution lies in the support of the findings of Bakker, Demerouti, De Boer, and Schaufeli (2003) within the higher education context. The empirical evidence provided, showed that poor and lacking resources within the university context preclude actual goal accomplishment, which is likely to cause failure and frustration and therefore may lead to withdrawal from work, and reduced motivation and commitment. The results furthermore explicate the additional stressful challenges that ODL university staff experience with regard to resources and demands. A number of differences were revealed between the stressors experienced by academic and administrative staff.

With regard to job overload, it seems that staff, especially in academic positions, experience increased time pressure, work overload, and concomitant increased levels of stress, which may lead to ill health and reduced commitment over the long term, if not addressed. This finding is in line with the drive towards excellence in university academic staff performance, performance measurement, assessment, and accountability, giving rise to high stress levels, observed by O'Connor and O'Hagan (2015) among universities from The Netherlands, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

On the contrary, the results indicated that administrative staff members in this ODL university often experience stress as a result of a lack of opportunities to grow and develop. The lack of these job resources may hinder administrative employees in achieving their work goals and facilitating personal growth, learning, and development, as predicted by Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner et al. (2001). It is strongly advised that the university invest in planned talent management strategies for administrative staff, to enable them to grow and develop in their positions.

This study found that the academic staff members experienced high levels of job insecurity. This is in line with what previous studies found in the United Kingdom (Tytherleigh et al., 2007), China, and Australia (Sun et al., 2011). It is thus recommended that the ODL university involved would pay attention to academics' experience of a lack of job security, in an effort to reduce their stress levels.

With regard to job control, it seems that staff feel that they have little control over many aspects of their job (autonomy) and have little or no influence over their performance targets. Individuals who experience little control are inclined to experience higher levels of stress and be less committed to work. This finding is supported by Coetzee and Rothmann (2005), who found that employees perceived control as a big source of stress and as a result perceive the organisation as less committed to them, and therefore also become less committed to the organisation.

Conclusions

Occupational stress among university staff members deserve dedicated research attention, especially given the fact that it is a global phenomenon. Continuous research to monitor university staff's wellbeing is necessary and we recommend that this research be expanded to include a larger and more diverse proportion of administrative and academic staff's stressors. The conceptual framework raises several questions that could be explored further through alternative or longitudinal research approaches. Other limitations include the use of a cross-sectional survey design, limiting the investigation of causal relationships. It is furthermore difficult to establish the time sequence of events. Secondly, the self-report measure involves subjective perceptions. However, despite these limitations, this study utilised a standardised measurement instrument, customised for the South African environment, previously used in higher education scenarios. Furthermore, cross-validation is evident in the quantitative and qualitative findings that complement one another with pertinent occupational stress and risk factors identified, to be addressed among administrative and academic staff respectively.

A clear need is articulated indicative of the importance to restructure positions within which realistic expectations with clear and transparent job descriptions are defined. Sufficient and effective support functions to support staff members when needed are imperative, especially with regard to the increasing administrative task demands. Eliminate unnecessary administration and duplication where possible. Identify individuals with a need and potential to cope well with task diversification that could contribute to job enrichment and utilise graduate students under supervision as part of personal research teams. Staff members, who have proven themselves competent, need to be empowered with greater decision-making authority. Research interests need to be salvaged and academics on all levels need more time for their scholarly pursuits while serving departments. Dissatisfaction occurs when time for research is put aside, resulting in additional distress and at times also burnout. Lastly, timeous identification of stressors present need to be addressed. Whilst the intensity in which these pressures are experienced may be relative to the respective staff member, however, the manner in which stressors are dealt with can be crucial to prevent escalation of problems.

As the higher education sector continues to battle turbulent times of change and upheaval, it is imagined that these findings may provide a new vantage point on some of the difficulties faced by people working within the industry. As people battle to maintain mental health issues within their various professions, the higher education sector is no exception. It is hoped that the new knowledge presented in this article will facilitate a deeper psychological understanding of how people experience the stressors within the university system. An improved understanding is essential for managers and policy makers to address these issues to the benefit of the whole higher education community, including academics, administrative staff, learners, and all other stakeholders involved.

References

Ablanedo-Rosas, J. H., Blevins, R. C., Gao, H., Teng, W., & White, J. (2011). The impact of occupational stress on academic and administrative staff, and on students: An empirical case analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(5), 553-564.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., De Boer, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 341-356.

Barbour, R. S. (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal, 322, 1115-1117.

Barkhuizen, N. E., & Rothmann, S. (2005). Occupational stress of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. South African journal of psychology, 28(2). doi: 10.1177/008124630803800205

Brough, P., Dollard, M. F., & Tuckey, M. R.. (2014). Theory and methods to prevent and manage occupational stress: Innovations from around the globe. International Journal of Stress Management, 21(1), 1-6. doi: 10.1037/a0035903

Catano, V., Francis, L., Haines, T., Kirpalani, H., Shannon, H., Stringer, B., & Lozanzki, L. (2010). Occupational stress in Canadian universities: A national survey. International Journal of Stress Management, 17(3), 232-258. doi: 10.1037/a0018582

Chaudhry, A. Q. (2012a). The relationship between occupational stress and job satisfaction: the case of Pakistani universities. International Education Studies, 5(3), 212-221.

Chaudhry, A. Q. (2012b). An analysis of relationship between occupational stress and demographics in universities: the case of Pakistan. Bulletin of Education and Research, 34(2), 1-18.

Coetzee, S. E., & Rothmann, S. (2005). Occupational stress, organisational commitment and ill-health of employees at a higher education institution in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(1), 47-54.

Courtney, K. (2013). Adapting Higher Education through changes in academic work. Higher Education Quarterly, 67(1): 40-55.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Geurts, S. A. E., & Taris, T. W. (2009). Daily recovery from work-related effort during non-work time. Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being, 7, 85-123.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Shaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499-512.

Gill, J. (2009, April 9). By the role divided. Times Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/by-the-role-divided/406078.article

Giorgi, G. (2012). Workplace bullying in academia creates a negative work environment: An Italian study. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 24, 261-275.

Grant, G. F., Ali, E. A., Thorsen, E. J., Dei, G. J., Thorsen, E. J., & Kathryn, L. (1995). Occupational stress among Canadian College Educator: A review of the literature. College Quarterly, 3(2), 102-108.

Höbfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513-524.

Höbfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337-421.

Höbfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307-324.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

Jackson, L., & Rothmann, S. (2006). Occupational stress, organisational commitment, and ill-health of educators in the North West Province. South African Journal of Education, 26(1), 75-95.

Jahanzeb, H. (2010). The impact of job stress on job satisfaction among academic faculty of a mega distance learning institution in Pakistan. A case study of Allama Iqbal Open University. Mustang Journal of Business and Ethics, 1, 31-49.

Krippendorf, K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). The Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania. Los Angeles: Sage.

Kyvik, S. (2013). The academic researcher role: Enhancing expectations and improved performance. Higher Education, 65, 525-538.

Lentell, H. (2012). Distance learning in British universities: is it possible? Open Learning, 27(1), 23-36.

Marten, S. (2009). The challenges facing academic staff in UK Universities. Retrieved from http://www.jobs.ac.uk/careers-advice/working-in-higher-education/1350/the-challenges-facing-academic-staff-in-uk-universities

Maslach, C., Shaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397-422.

Meng, Q., Xu, L., & Xu, X. (2014). Applying game theory to the balance between academic and administrative power in universities. Social Behavior and Personality, 42(6), 913-920.

Moorhead, G., & Griffin, R. W. (2001). Organizational behaviors managing people and organizations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Nicklin, J. M., McNall, L. A., Cerasoli, C. P., Varga, C. M., & McGivney, R. J. (2016). Teaching online: Applying Need-theory to the Work-Family interface. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(3), 167-179. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2016.1187042.

Ntshoe, I., Higgs, P., Higgs, L. G., & Wolhuter, C. C. (2008). The changing academic profession in higher education and new managerialism and corporatism in South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 22(2), 391-403.

O'Connor, P., & O'Hagan, C. (2016). Excellence in university academic staff evaluation: A problematic reality? Studies in Higher Education, 41(11), 1943-1957

Pasca, R., & Wagner, S. L. (2011). Occupational stress in the multicultural workplace. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health, 13(4), 697-705. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9457-6.

Pitman, T. (2010). Perceptions of academics and students as customers: a survey of administrative staff in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 22(2), 165-175.

Polster, C. (2012). Reconfiguring the academic dance: a critique of faculty's responses to administrative practices in Canadian universities. TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, 1(28), 115-141.

Pon, K., & Lichy, J. (2015). For better or for worse: the changing life of academic staff in French business schools. Journal of Management Development, 34(5), doi: htttp://dx.doi.org//10.1108/JMD-03-2014-0022.

Qualtrics. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.qualtrics.com

Rocca, A. D., & Kostanski, M. (2001). Burnout and job satisfaction amongst Victorian, Secondary school teachers: a comparative look at contract and permanent employment. Paper presented at the ATEA conference on Teacher Education: Change of heart, mind and action (pp. 24-26), September, Melbourne, Victoria.

Rothmann, S., Mostert, K., & Strydom, M. (2006). A psychometric evaluation of the job demands-resources scale in South Africa. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 32(4), 76-86.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 893-917.

Schuldt, B. A., & Totten, J. W. (2008). Technological factors and business faculty stress. Proceedings of the Academy of Information and Management Sciences, 12(1), 13-18.

Selye, H. (1983). The stress concept: Past, present and future. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Stress research: Issues for the eighties (pp. 1-20). New York, NY: John Wiley.

Siltaloppi, M., Kinnunen, U., & Feldt, T. (2009). Recovery experiences as moderators between psychosocial work characteristics and occupational well-being. Work & Stress, 23(4), 330-348.

Sun, W., Wu, H., & Wang, L. (2011). Occupational stress and its related factors among university teachers in China. Journal of Occupational Health, 53, 280-286.

Szekeres, J. (2011). Professional staff carve out a new space. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(6), 379-691.

Tagurum, Y. O., Okonoda, K. M., Miner, C. A., Bello, D. A., & Tagurum, D. J. (2017). Effect of technostress on job performance and coping strategies among academic staff of a tertiary institution in north-central Nigeria. International Journal of Biomedical Research, 8(6), 312-319. doi: https://doi.org/10.7439/ijbr

Teelken, C. (2011). Compliance or pragmatism: How do academics deal with managerialism in higher education? A comparative study in three countries. Studies in Higher Education, 37(3), 271-290.

Tustin, D. H., Ligthelm, A. A., Martins, J. H., & Van Wyk, H. de J. (2005). Marketing research in practice. Pretoria: Unisa Press.

Tytherleigh, M. Y., Webb, C., Cooper, C. L., & Ricketts, C. (2007). Occupational stress in UK higher education institutions: a comparative study of all staff categories. Higher Education Research and Development, 24(1), 41-61. doi: 10.1080/0729436052000318569

UNISA. (2007). Unisa policy on research ethics. Retrieved from http://www.unisa.ac.za/contents/research/docs/ResearchEthicsPolicy_apprvCounc21Sept07.pdf

Van den Broeck, A., Van Ruysseveldt, J., Vanbelle, E., & De Witte, H. (2013). The job demands-resources model: overview and suggestions for future research. Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology, 1, 83-105. doi: 10.1108/S2046-410X(2013)0000001007

Wallace, M., & Marchant, T. (2011). Female administrative managers in Australian universities: not male and not academic. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(6), 567-581.

Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

White, M. D., & Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends, 55(1), 22-45.

World Health Organisation. (2018). Occupational health stress at the workplace. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/occupational_ health/topics/stressatwp/en/

Ylijoki, O. H., & Ursin, J. (2013). The construction of academic identity in the changes of Finnish higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(8), 1135-1149.

Zhang, L. F. (2012). Personality traits and occupational stress among Chinese academics. Educational Psychology, 32(7), 807-820.

Mental Health in Higher Education: A Comparative Stress Risk Assessment at an Open Distance Learning University in South Africa by Jacolize Poalses and Adéle Bezuidenhout is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.