R. A. Aderinoye, K. O. Ojokheta, & A.

A. Olojede

University of Ibadan, Nigeria

The establishment of the Nigerian National Commission for Nomadic Education in 1989 created wider opportunities for an estimated 9.3 million nomads living in Nigeria to acquire literacy skills. This commission was struck to address low literacy rates among pastoral nomads and migrant fishermen, which put literacy rates at 0.28 percent and 20 percent respectively (FME, 2005). To improve the literacy rate among Nigeria’s nomadic populations, the National Commission for Nomadic Education employed various approaches such as onsite schools, ‘shift system’ schools with alternative intake, and Islamiyya (Islamic) schools, to provide literacy education to its nomads. A critical appraisal of these approaches by the commission, however, shows that very few of the schools were actually viable. This paper explores why these approaches have not notably helped to improve the literacy rate among Nigeria’s nomadic people. Thus, there remains a need for alternative approaches to educational delivery. In face of the revolutionary trends taking place in information and communication technologies (ICTs) in Nigeria, there is now opportunity to embrace mobile learning using low cost mobile technologies (i.e., mobile phones) to enhance the literacy rates among Nigeria’s nomadic people, some of whom are enrolled in Nigeria’s current Nomadic Education Programme. Indeed, mobile telephones with simple text messaging features, for example, are prevalent in many parts of Nigeria. This paper explores the needs and advantages of integrating mobile learning into Nomadic Education programmes in Nigeria to ensure a successful implementation and achievement of the goals of the programme.

Keywords: Mobile learning; nomadic education; information and communication technologies; ICT; radio literacy; distance education

Article 13 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (UNESCO, 2003) articulates:

Education is both a human right in itself and indispensable means of realising other human rights. As an empowerment right, education is the primary vehicle by which economically and socially marginalized adults and children can lift themselves out of poverty and obtain the means to participate fully in their communities. Education has a vital role in empowering women, street working children from exploitative and hazardous labour and sexual exploitation, promoting human rights and democracy, protecting the environment, and controlling population growth (UNESCO, 2003, p. 7).

Clearly, achieving the right to education for all is one of the biggest challenges of our times. The second ‘International Development Goal’ addresses this challenge through the provision of universal primary education in all countries by 2015.

The centrality and importance of education as a fundamental ‘human right’ has been well documented in the literature. According to Ezeomah (1983; 1982) and Aleyidieno (1985) making education a fundamental ‘human right’ provides a viable springboard for transforming social and economic policy (as cited in Iro, 2006). For example, Wennergreen, Antholt, and Whitaker (1984) suggest:

All who have mediated on the art of governing mankind have been convinced that the fate of empire depends on the education of youth (p. 34).

From the foregoing, it is clear that any nation looking for a lasting economic success must raise the literacy level of its citizens. The educational provision in Nigeria, as written in its National Policy on Education (FME, 2004) first published in 1977, has articulated five main national goals:

Therefore, Nigeria’s philosophies of education are based on:

To this effect, the establishment of various institutions like the National Mass Education Commission in 1999, State Agencies of Adult Education, and most especially, the National Commission for Nomadic Education in 1989, created a wider opportunities for the estimated population of 9.3 million Nigerian nomads. The nomadic population of Nigeria currently makes up approximately 6.8 percent of its total estimated population of 140 million people (NPC, 2006).

While proportionally small, Nigeria’s nomadic people represent a sizable population that needs access to basic educational provisions to acquire literacy skills. Education is widely considered as an authentic and necessary tool for national development. Every segment of Nigerian society must therefore have access to education, including Nigeria’s relatively small nomadic population.

Nigeria’s nomadic people are typically described in terms of what they do not have. They do not have access to adequate food, clean water, health care, clothes, or shelter. They do not possess basic literacy skills. Their children do not have access to basic education. Young female nomads do not have the cultural freedom to marry who they want to marry. Nigeria’s nomads, therefore, arguably need a better understanding of their socio-cultural predicament, which many consider as less developed.

Educating Nigeria’s nomadic populations via distance education (and using mobile-learning methods), can be viewed as a positive step towards effective implementation of the provision of Nigeria’s National Policy on Education (NPE) on equal access and brighter opportunities for all its citizens regardless of where they live. The establishment of nomadic schools in Nigeria’s various nomadic States, however, has failed to produce desired results because of the non integration of mobile learning technologies.

The literature has identified mobile learning as any service that supplies a learner with general electronic information and educational content that aids in acquisition of knowledge regardless of location and time (Lehner & Nosekabel, 2002).

In recent years, there has been a steady growth in Nigeria’s mobile telephone infrastructure and a concomitant acquisition and hence, use of mobile telephones amongst Nigerians. Increasing rates of accessibility throughout Nigeria is encouraging more and more people to have access to, or purchase, a mobile phone. Service providers in Nigeria are also on the increase to meet this growing demand, and over time, interconnectivity is projected to be both easier and more affordable, especially for Nigeria’s nomadic population.

‘Literacy by Radio’ is an educational programme that has been implemented throughout the country. Indeed, radio currently provides instructions and relays messages to Nigeria’s nomads, who are typically on the move while grazing their cattles. The provision of tele-centres that provide Nigeria’s rural and nomadic peoples with practical skills acquisition are currently being used to teach topics such as health and socio-economic issues that affect their daily lives. Further, from a pedagogical perspective, Kinshuk (2003) believes mobile learning will serve a whole new highly mobile segment of society, a reality that could very well enhance the flexibility of the educational process. Chen, Kao, Sheu, and Chiang (as cited in Milrad, Hoppe & Kinshuk, 2003) say that characteristics of mobile learning must include:

According to Kinshuk (2003), mobile learning facilitates provision of educational opportunities. In the Nigerian context, Kinshuk’s (2003) work can be expanded to include the integration mobile learning into nomadic educational contexts and programmes. The principle of this paper is based on this contextual and pedagogical viewpoint.

Mobile learning is the use of any mobile or wireless device for learning on the move. It is any service or facility that supplies a learner with general electronic information and educational content that aids their acquisition of knowledge, regardless of location and time (Lehner & Nosekabel, 2002). Kinshuk (2003) in quoting Vavoula and Sharples (2002) suggested that there are three ways in which learning can be considered mobile: (1) learning is mobile in terms of space; (2) in different areas of life; and (3) with respect to time. These definitions, according to Kinshuk (2003), suggest that mobile learning systems should be capable of delivering educational content to learners anytime and anywhere they need it.

Mobile learning, as a novel educational approach, encourages flexibility; students do not need to be a specific age, gender, or member of a specific group or geography, to participate in learning opportunities. Restrictions of time, space and place have been lifted.

Mobile technologies enable students to become more adaptable to flexible and contextual lifelong learning, a situation defined by Sharples (2000) as the “knowledge and skills” people need to prosper throughout their lifetime. Clearly, these activities are not confined to specified times and places; however, they are very difficult to achieve through traditional education channels. Put simply, mobile technologies fulfill the basic requirements needed to support contextual, life-long learning by virtue of its being highly portable, unobtrusive, and adaptable to the context of learning and the learners’ evolving skills and knowledge (Sharples, 2000).

According to Akinpelu (1993), the contemporary definition of ‘nomadism’ refers to any type of existence characterized by the absence of a fixed domicile. He identifies three categories of nomadic groups as: hunter/ food gatherers, itinerant fishermen, and pastoralists (a.k.a., herdsmen).

In Nigeria, there are six nomadic groups:

The last group, The Fishermen, is concentrated in Rivers, Ondo, Edo, Delta, Cross River, and Akwa-Ibom States (FME, Education Sector Analysis, 2000). The first five nomadic groups listed are considered pastoralist nomads.

Delivery of educational services to the children of all nomadic groups has tended to follow the lines of the formal school system. Special attention was paid to these groups by the Nigerian Government when it set-up the National Commission for Nomadic Education by Decree 41 of 12 December 1989 (Federal Government of Nigeria, 1989).

Of the estimated 9.3 million people that currently comprise Nigeria’s nomadic groups, approximately one third, that is 3.1 million are of school and pre-school age. The pastoral nomads are more highly disadvantaged than the migrant fishermen, in terms of access to education primarily because they are more itinerant. As a result, the literacy rate of pastoral nomads is only 0.28 percent, while that of the migrant fishermen is about 20 percent (FME, 2000). The basic responsibility of the Commission for Nomadic Education, among others, is to provide primary education to the children of pastoralist nomads – a responsibility shared with the States and Local Governments. To provide education to its nomads,a multifaceted strategy has been adopted by the Commission, that includes on-site schools, the ‘shift system,’ schools with alternative intake, and Islamiyya (Islamic) schools. The current mobile school system in the strictest sense remains sparingly used, primarily due to the enormity of problems associated with this model. Some mobile schools, however, are in operation in the River Benue area of Taraba, Benue, Adamawa, Nassarawa, Borno, and Yobe Sates.

By the beginning of the 1995/ 1996 school session, there were 890 nomadic schools in 296 Local Government Areas of 25 States of the Federation catering for the education needs of the children of pastoral nomads alone. Of these, 608 schools are owned and controlled by States, 130 by Local Government, and 152 by Local Communities. Together they serve 88,871 pupils of the estimated population of the 3.1 million nomadic school-age children. Of this number, 55,177 (62%) were boys and 33,694 (38%) were girls. There were 2,561 teachers, a majority of whom 1,326 or 51 percent were teacher-aides, who are unqualified and in need of upgrading. This has been the usual practice because of the nature and characteristics of the nomadic populace.

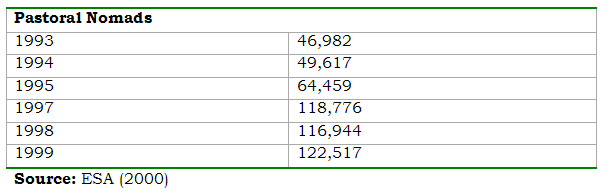

As of 1993, 661 schools had been built for pastoral nomads, out of which 24 percent (n = 165) had permanent classrooms and 46 percent (n = 293) had temporary classrooms built of grass, mats, canvas tarpaulins, et cetera. Subsequently, mobile, collapsible classrooms were procured. Altogether, the schools had an enrolment of 46,982 children taught by 1,896 teachers. This number, however, only scratches the surface of the problem, as it only serves an estimated 3.1 million primary school age nomadic children. The Comprehensive Education Analysis Project, (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2000) provides the enrolment figures during the 1990s in Table 1.

Table 1. Enrolment of Pastoral Nomads in the 1990s

Note that between 1993 (n = 46,982 students were enrolled) and 1999 (n = 122,517 students were enrolled), there has been an increase of 260.8 percent. Considering that there are an estimated 3.1 million pastoral nomads in Nigeria, however, there is still a long way to go.

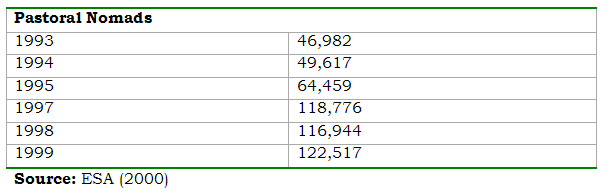

Table 2. Enrolment of Migrant Fishermen, 1998-99

In spite of these efforts, access to education is still a major problem affecting Nigeria’s pastoral nomadic people and migrant fishermen (see Tables 1 and 2).

To improve the literacy rate of Nigeria’s nomads, the National Commission for Nomadic Education employed various approaches such as on-site schools, the ‘shift system,’ schools with alternative intake, and Islamiyya (Islamic) schools to provide literacy education to the nomads. The nomadic education programme has a multifaceted schooling arrangement designed to meet the diverse habits of the Fulani people, with the largest population of 5.3 million. In Nigeria, the government set up different agencies to implement education for the nomads; these agencies include the Federal Ministry of Education; Schools Management Board; National Commission for Nomadic Education; Agency for Mass Literacy, and the Scholarship Board. Together, they offer a mobile school system wherein the schools and the teachers move with the Fulani children.

Mobile schools use collapsible classrooms that can be assembled or disassembled within 30 minutes and carried conveniently by pack animals. While a whole classroom and its furniture can be hauled by only four pack animals, motor caravans are replacing pack animals to move the classrooms. A typical mobile unit consists of three classrooms, each with spaces to serve 15 to 20 children. Some classrooms are equipped with audio-visual teaching aids.

In a study jointly carried out by the Federal Government of Nigeria and UNESCO in 2004, “Improving Community Education and Literacy, Using Radio and Television in Nigeria,” it was established that 37.0 percent of Nigerians owned only radio, while 1.3 percent owned only TV sets. Nearly forty-eight percent (47.8%) owned both radio and TV sets, while 13.9 percent had neither. Findings from the study revealed that radios are easily affordable, accessible, and often more handy to use than TV. Those without TV and radio, however, still have access to the media through socialization in their local communities.

The pastoral Fulani as a captive audience for radio and television programmes have radios, which they carry along during herding. The literate world can, thus, reach itinerants Fulani without disrupting their nomadic life or livelihood. To improve literacy, especially in the rural areas, the Nigerian Government has introduced radio and television educational programmes. The government supplies hardware such as radio, television, and electric generators, and builds viewing rooms for public use.

Although the Nigerian Government has spent millions of naira (the currency of Nigeria) to support its nomadic education programme, educational attainment among the Fulani remains low, and the quality of education among them is mediocre at best. The current form of nomadic education, therefore, has truly yet to lift the literacy and living standards of the Fulani people as children of farmers rather than fulanis constitute up to 80 percent of the pupils in nomadic schools. In Plateau State, for example, only six of 100 children in the Mozat Ropp nomadic school are Fulani (Iro, 2006).

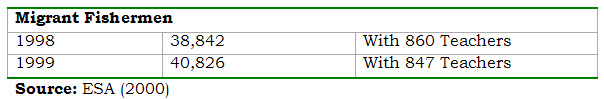

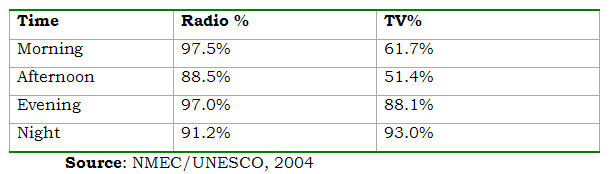

Time of tuning to radio or TV varies according to programmes of interest and the time of the day, when the audience’s attention is most available. Table 3 indicates the time when most Nigerians tune to radio and television.

Table 3. Time and Audience in Nigeria

Table 3 shows that Nigerians tuned to radio all day long. Of those surveyed, 97.5 percent indicated that they listened to radio in the morning, 88.5 percent in the afternoon, while 97 percent and 91.2 percent listen in the evening and night, respectively. Of those surveyed, 61.7 percent view television in the morning, 51.4 percent in the afternoon, 88.1 percent in the evening, and 93 percent in the night. These findings indicate that higher percentages of Nigerians tune into radio and television during the evening and at night.

These findings suggest that scheduling of education programmes for community education purposes (i.e., nomadic educational programmes) will be more effective if broadcasts are transmitted when audiences are most available and, arguably, attentive.

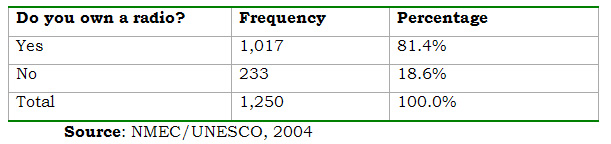

Ownership of radios naturally leads to radio listening habits. It is expected that all members of a household will have access to radio (if available). Table 4 analyses the pattern of ownership of radios in Nigeria.

Table 4. Distribution of radios by heads and members of households in Nigeria

Table 4 above shows that 81.4 percent of Nigerians own a radio, while 18.6 percent had none. This shows that radios are readily available. The implication is that four out of every five members in any community own a radio. Broad access to radio arguably facilitates the flow of information to both urban and rural areas, and can assist in the development of community education, especially at the grassroots.

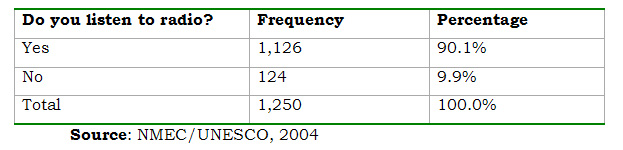

Audience listening habits develop based on overall availability of radio in the community. Table 4 shows that radios are readily available, primarily because they are affordable and easy to operate in both rural and urban centres. Table 5 below examines the listening habits of Nigerians, which supports the findings in Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Education (2005), ESA Study.

Table 5. Frequency distribution of listening habits

Table 5 shows that 9 out of every 10 Nigerian adults listen to radio. Analysis by State, also shows the same pattern with more State recording higher percentage of between 90 percent and 100 percent. As noted earlier, the accessibility to radios accounts for the high listening habits. Table 6 below examines how Nigerian’s listen.

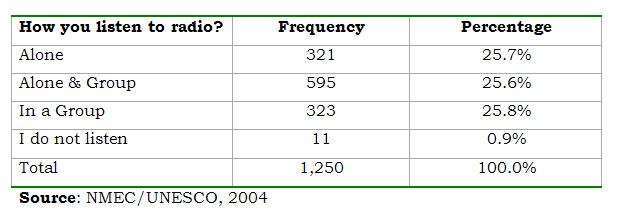

Table 6. Mode of radio listening in Nigeria

The mode of listening in Table 6 indicates that the pattern of radio listening habits are uniformly distributed among those listening alone (25.7%), listening in-group (25.8%), and alone or in-group (47.6%). It is observed that across the States, listening habit ‘alone or in-group’ is higher than others. In fact, the ‘alone or in-group’ mode of listening is nearly the same as Nigerian’s TV viewing habits, with the exception of radio sets, which are more easily transportable. Group listening provides opportunity to discuss various programmes of interest and is arguably a good forum to develop education programmes.

The ESA (2000) study also examined Nigerians’ television viewing habits. The purpose of this study was to determine possible prerequisites to watching educational programmes in various communities. The survey was administered to 60 percent rural people and 40 percent for urban people. This distribution is indicative in itself, as the target of this study centred on Nigeria’s nomadic populations based in its rural areas; it was also based on fact that demographically more than half of Nigeria’s population live in rural areas.

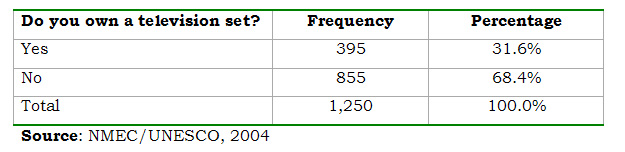

Ownership of television sets can be viewed as a yardstick upon which to predict and, arguably, cultivate television-watching habits, especially for the use of tele-centres as a distance learning method. In Nigeria, households that have a television not only attract viewers from within the immediate family, it can attract extended family members in the neighbourhood, and even neighbours who may also be interested in the programme aired. With the introduction of Rural Electrification Projects in many communities throughout Nigeria, more areas and regions are now being opened-up to modern technologies. Put simply, televisions are no longer a foreign sight in rural areas. Moreover, some televisions can be operated on batteries, which overcomes problems of electrical shortages and blackouts. Table 7 below shows the home ownership of television sets as a prerequisite to developing television viewing habits.

Table 7. Distribution of household ownership of televisions in Nigeria

Table 7 above indicates that only 31.6 percent of Nigerians own television sets. The percentage of those without television sets is higher due to poverty and low incomes of many Nigerians. This study also reveals that radios are more affordable, and hence attainable, than television sets. Indeed, many Nigerians face difficult times as many families have been affected by retrenchment, under-employment, and unemployment in recent times. This creates and perpetuates a situation whereby many adult Nigerians – who are often struggling to support and feed their families – cannot afford luxury goods like televisions.

Due to the exchange rate of the naira, the exchange currency of Nigeria, problems of inflation also abound. For example, the exchange rate of the naira in 1986 was N .7550 to US $1.00; in 2006 it was N 137.00 to US $1.00. This means many consumer goods, including television sets, are financially out-of-reach of most Nigerians who lack discretionary cash and hence, buying power. To further exacerbate problems brought about by pressures of high inflation, electrical failures are common throughout Nigeria, a reality that further discourages many Nigerians from buying power-hungry appliances and durable goods like television sets. The major source of electricity is government owned. In Nigeria’s cities, where electricity does exist, power interruptions are very common, while most rural areas altogether lack the electrical infrastructure to power televisions.

The social structure of Nigerians encourages communal living, which encourages people within the same household or community to share things. This is especially true for the nomadic families. Nomadic people tend to share whatever they have without grudge; thus, their ‘culture of sharing’ encourages communal television viewing and as such, should advance the use of tele-centres to accommodate literacy programmes aimed at teaching nomadic populations.

The role of the National Commission for Nomadic Education (which does not have a school of its own) is to provide instructional and infrastructural support to schools catering for nomads, and conduct training courses for teachers working in nomadic schools. The reality is, however, Nigeria’s States and Local Governments tend not to coordinate their activities to support this programme; they also make little effort to discover what is happening in the schools. Infrastructure and facilities that were provided during the mobilization period – 1988 to 1990 – have either been destroyed or dismantled, and replacement and renovation have not taken place. The demise in 1991 of the National Primary Education Commission, which by law allocated 2.5 percent of the National Fund to support Nomadic Education, affected the funding of the Nomadic Education Commission until a new Primary Education Commission (NPEC) was re-established in 1993. The re-injection of funding has improved the situation.

In sum, nomadic education in Nigeria is affected by defective policy, inadequate finance, faulty school placement, continual migration of pupils, unreliable and obsolete data, and cultural and religious taboos (UBE, 2006). While some of these problems can be solved by policy and infrastructure interventions, the fact remains that most problems are complex and difficult to solve. The persistence of these problems is causing the roaming Fulani to remain educationally deficient.

The current top-down planning process, wherein the Fulani are the passive recipients rather than proactive planners of their education, dominates the nomadic education policies. For instance, during the first national workshop on nomadic education, only a few Fulani were invited to attend. Ironically, it was at this particular workshop that far-reaching decisions that affected the lives of the Fulani were made (Iro, 2006). Writing about education among the East African pastoralists, Iro stated further “Pastoralist, in our education system, get knocked on the head, being told they don’t know anything . . . although they, in fact, come in with knowledge that even if we studied half our lives, we wouldn’t achieve” (p. 194). This is exactly what is happening to the pastoralist Fulani in Nigeria. The Fulani are concerned that their children who go to school will graduate with ideas that will be at odds with their traditional pastoral practices. In quoting a Fulani leader, Iro (2006) wrote “. . . we are not opposed to the idea of getting our children to schools, but we fear that at the end of their schooling they will only be good at eating up cattle instead of tending and caring for them” (p. 51).

Beyond the use of technology in formal education programmes for adults, wherein computer skills and other components of ‘digital literacy’ often define a given programme’s learning objectives, distance learning supported by ICTs, can provide significant learning opportunities for informal and non-formal continuing literacy in adults and in basic youth education programmes. Indeed, four high-population countries – Cuba, China, Mexico and Nigeria – have each shown that the combination of distance education and ICT can and does work.

Distance learning and ICTs enable interaction and practice, use leaner-generated materials, stimulates learner awareness and learner motivation, supports and trains literacy workers, facilitates the distribution of materials and information to resource centres, and gathers feedback from centres and individual learners regarding available materials and programmes (Iro, 2006). It is rare, however, for adult literacy programmes to be conducted solely through these media, which primarily are used in support of conventional educational programmes in Nigeria. Interestingly, Cuba has used the combination of the above mentioned media to successfully promote literacy. Cuba’s track record of success, in essence, shows that Nigeria can borrow a leaf from Cuba’s experience.

Some scholars recognize that access to technology does not guarantee that its use will be meaningful or empowering. Instead, the real challenge facing educators is to shift students from acquisition of technical skills to that of proactively determining how digital technologies can enable them and others to engage in social and academic pursuits (Hayes, 2003). Indeed, emphasizing individual instruction and individual ownership of technology at the expense of sound pedagogy could, in fact, widen rather than bridge the ‘digital divide.’ Given such pedagogical and resource constraints, ICTs and distance learning have more immediate potential for the professional development of literacy educators than for literacy programmes themselves per se.

Nigeria’s telecommunications infrastructure and its use are rapidly expanding. The popularity and relative affordability of text messaging, for instance, suggest that it could be used for mass distribution of messages to learners and to facilitate communication among learners, and between learners and their distance trainers.

Radio continues to be the most potent tool for use in literacy development. Locally produced interactive radio instruction, along with community radio for locally specific programme support, can allow two-way engagement among learners and programme providers, especially where potential learners are widely scattered or mobile, such as is the case with the newly introduced literacy by radio for all. One good thing about the radio literacy is its relevance on local languages: Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, Kolokuma, Fulfide, and Ijaw. Radio is also used for awareness generation and community mobilization (Aderinoye, 2005). Use of cassettes offer still more potential for genuine multimedia pedagogy to enrich functional teaching in literacy courses. In some cases, they could even be the primary tool used to teach basic literacy skills. Support in the form of cassettes relies on fairly simple technology; albeit one that includes a system of making and distributing recordings. It also requires extra visits by local coordinators/ supervisors to distribute cassettes. Still cassettes can be reused – for instance, for in-service support purposes.

The terms “distance education” or “distance learning” have been used interchangeably by many different researchers in a variety of programs, providers, audiences, and media. Its hallmarks are the separation of teacher and learner in time and/ or space (Perraton, 1988), and noncontiguous communication between student and teacher, mediated by print or some form of technology (Keegan, 1986; Garrison & Shale, 1987). It does not imply the physical presence of the teacher appointed to dispense learning in the place where it is received, or in which the teacher is present only on occasion (Kaye, 1989).

Distance education is an important component of non-formal education that caters to those that lack access to traditional, bricks and mortar and four walled institutions to learn. This form of education through mass media and correspondence makes access to health education, civic education, literacy, and vocational training possible (Abiona, 2003). Through distance education modalities, relevance is also attached to the improvement of personal improvement, especially for Nigeria’s nomadic populations whose lifestyles do not permit them to participate in Nigeria’s conventional school system. There is, of course, the need for further, more in-depth research (i.e., curriculum design, media used, personnel work release, equipment, initiatives, etc.

According to Slavin (1990) two theoretical models support the relevance of using distance education in the context of nomadic education. The first model, ‘motivational theory,’ suggests that the motivation of each learner working with other students in cooperative learning contexts is high. That is, the combination of well-planned learning environment wherein the learner knows the goals will increase his or her motivation to learn. The other explanation, ‘cognitive learning theory,’ relates to learners’ cognitive processes occurring during cooperative learning. Because cooperative learning involves dialogue and interaction between learners, students are more likely to grasp the conceptual material under study.

In a recent Mobile Telecommunication Nigeria (MTN) advertisement, a Fulani pastoralist is depicted making a call and telling other Fulani friends that MTN network was now available, even in the remotest regions. This advertisement portrays the fact that pastoralists – like other Nigerians – can also use mobile telephones wherever and for whatever reason. In terms of using mobile technologies to teach basic literacy skills to Nigeria’s nomadic pastoralists, one of the most practical mobile technologies currently available are mobile telephones. The processes of using mobile phones for educational purposes can be illustrated as:

Mobile learning systems, to a great extent, are capable of delivering educational content anytime and anywhere learners need it. In this regard, there are many benefits that Nigeria’s nomadic populations can draw upon if mobile learning is integrated into Nigeria’s current nomadic education programme. Some projected benefits are:

Of course, other, perhaps hidden, challenges still must be faced in the integration of mobile learning into nomadic education programmes in Nigeria. Some apparent challenges are:

The processes described certainly look novel. Most innovative ideas usually start as something – a project or a technology – that looks funny or virtually impossible, before they are implemented and subsequently widely accepted (Rogers, 1995). However, because current approaches to addressing problems of nomad literacy have been found to be inadequate, trials of innovative ideas, such as mobile phones for mobile learning, is worth the expense and effort. Mobile technologies have been found to be very relevant in certain educational contexts. Nigeria’s pastoralists and nomads are equally aware of the importance of these technologies as portrayed in the Mobile Telecommunication Nigeria advertisement. Procuring mobile phones for these nomadic groups of learners will not only motivate them and instill positive attitudes towards learning, it will also help to sustain their interest in gaining literacy skills, especially through the distance learning approach. It is high time Nigeria joined the League of Nations in promoting mobile learning as a pedagogical approach to increase both relevancy of education and access to education.

Abiona, K. (2003). The Use of Media in Adult Education. A paper presented at a one day workshop organised for Local Adult Literacy Officers of Agency for Adult and Non-Formal Education. Oyo State, Nigeria.

Aderinoye, R. A. (2005). Innovation in Mass Literacy Promotion in Nigeria: the intervention of the Cuban Radio Literacy Model. 2005 ICDE International Conference, November 19-23. New Delhi, India.

Akinpelu, J. A. (1993). Education for special groups. In O. O. Akinkugbe (Ed.) Nigeria and Education: The challenges ahead (p. 23). Second Obafemi Awolowo Foundation Dialogue. Ibadan: Spectrum Books.

Aleyidieno, S. (1985). Education and Occupational Diversification Among Young Learners: The problem of harmonising tradition practices with the lessons of our colonial heritage. In Issues on Development: Proceedings of a Seminar held in Zaria. January 12-13. Zaria, Nigeria: Ahmadu Bello University Press.

Chen, Y. S., Kao, T. C., Sheu, P. P., & Chiang, C. Y. (2002). A Mobile Scaffolding: Aid-based bird-watching learning system. In M. Milrad, H. U. Hoppe, & Kinshuk (Eds.) IEEE International, Workshop on Wireless and Mobile Technologies in Education (pp. 15-22). Los Alamitos, CA.: IEEE Computer Society.

Ezeomah, C. (1982). Movements and Demography of Fulani Nomads and their implications for Education Development. Published in the proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on the Education of Nomads in Nigeria, Jos, Nigeria

Ezeomah, C. (1983). The Education of Nomadic People: The Fulani of Northern Nigeria. In Ver Eecke, C. (1989) Nigeria’s Experiment with a National Programme for Nomadic Education. Ohio Centre for African Studies: The Ohio State University.

Federal Republic of Nigeria (2004). National Policy on Education (NPE) 4th Edition. Abuja: NERC Press, Yaba.

Federal Ministry of Education (2005). Education Sector Analysis (ESA). Abuja: FME Publication.

Federal Ministry of Education (2004). National Policy on Education 4th Edition. Abuja: FME Publication.

Federal Ministry of Education (2000). Comprehensive Education Analysis Project (Secondary Data Report) Lagos: FGN/UNICEF/UNDP.

Federal Government of Nigeria (1989). Federal Government of Nigeria, NCNE Decree 41 of 2. December 1989. Lagos.

Garrison, R., & Shale, D. (1987). Mapping the Boundaries of Distance Education: Problems in defining the field. The American Journal of Distance education, 1(1), 7-13.

Iro, I. (2006). Nomadic Education and Education for Nomadic Fulani. Retrieved May 18, 2007 from: http://www.gamji.com/fulani7.htm

Kaye, A. R. (1989). Distance Education. In Titmus, J. T. (Ed.) Lifelong Education for Adults: An international handbook. Oxford: Paragon Press.

Keegan, D. (1986). The foundations of distance education. London: Croom Helm.

Kinshuk (2003). Adaptive mobile learning technologies. Department of Information Systems: Massey University, New Zealand. Retrieved May 19, 2007 from: http://www.whirligig.com.au/globaleducator/articles/Kinshuk2003.pdf

Lehner, F., & Nosekabel, H. (2002). The Role of Mobile Devices in E-learning – First experience with a e-Learning environment. In M. Milrad, H. U. Hoppe & Kinshuk (Eds.) IEEE International Workshop on Wireless and Mobile Technologies in Education (pp. 103-106). Los Alamitos, CA.: IEEE Computer Society.

NMEC/ UNESCO (2004). National Commission for Mass Literacy, Adult & Non-Formal Education National Report on Improving Community Education and Literacy Using Radio and Television in Nigeria. Abuja: NMEC/ UNESCO.

NPC (2006). National Population Census. Abuja, Nigeria.

NMEC (1999). National Mass Education Commission Annual Report. Abuja, Nigeria.

Perraton, H. (1988). A theory for distance education. In D. Sewart, D. Keegan, & B. Holmberg (Eds.) Distance Education: International perspectives (pp. 34-45). New York: Routledge.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations, 4th Ed. New York: Free Press.

Slavin, R. E. (1990). Cooperative Learning: Theory, research and practice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice-Hall.

Sharples, M. (2000). The design of personal mobile technologies for lifelong learning. Computers & Education, 34(3), 177-193.

UBE (2006). Universal Basic Education Commission Study on the state of Non-Formal Education in Nigeria. Abuja. Retrieved June 12, 2007 from: http://www.ubec.gov.ng/about/index.html

UNESCO (2003). Right to Education: Scope and Implementation. General comment 13 on the right to education. UNESCO Economic & Social Council. Retrieved May 18, 2007 from: http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/file_download.php/c144c1a8d6a75ae8dc55ac385f58102erighteduc.pdf

Vavoula, G. N., & Sharples, M (2002) Kleos: A personal, mobile, knowledge and Learning Organisation System. In M. Milrad, H.U. Hoppe and Kinshuk (Eds.) IEEE International workshop on wireless and mobile technologies on Education (pp. 152-156) Los Alamitos, CA.: IEEE Computer Society.

Wennergreen, E., C. Antholt, & M. Whitaker, (1984). Agricultural Development

in Bangladesh. Boulder, CO.: Westview Press.