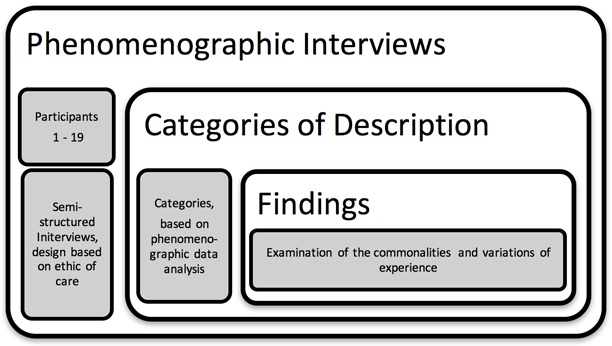

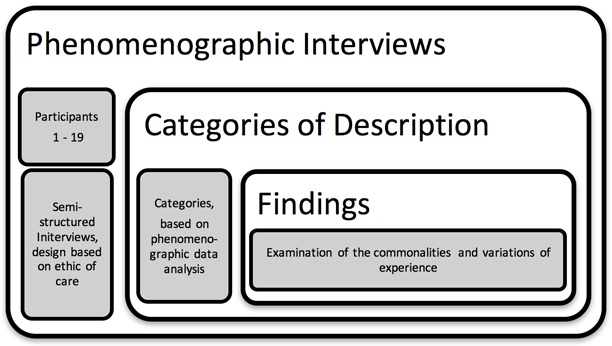

Figure 2. Research design for project. From The Ability to Access Post-Secondary Education: Adult Learners' Conceptions of Choosing Online Learning (p. 73), by K. Rasmussen, 2015, Lancaster University, UK. Copyright 2015 by Kari Rasmussen.

Volume 19, Number 5

Kari Rasmussen, PhD

University of Alberta, Canada

This research focused beyond the student, course, program, or institution by examining the conceptions of adults at the moment in time that they evaluated their choice to engage in furthering their post-secondary education by examining the possibilities provided through online learning. To capture their experience, not as students but as members of society, a practice of care framework, adapted from Tronto's (1993) work, was utilized as a theoretical framework. The use of this framework acknowledges that the practice of care is present in the lives of every human being and that each human being has received and/or provided care as part of their lived experience. A phenomenographical qualitative approach was the basis for the design of this project which allowed for the identification of the commonalities and variations of the described experience. All described experiences illustrated the balancing of needs, wants, and responsibilities, these descriptions included recognition of care of one's self, one's family, and one's community. The variation could be described as an expansion of the recognition of care, that is the focus of care expanded from self to family and then from family to community. This expansion occurred only in those described experiences that showed a strong conception of themselves within the previous category. The findings show that the choice to access online courses and/or programs provides possibilities for many adults that wish to continue their education but only if the educational environment can move away from its institutional centric perspective.

Keywords: online, elearning, higher education, phenomenography, qualitative, ethic of care, practice of care

Online learning has continued to experience substantive growth (del Valle & Duffy, 2009; Li & Akins, 2004; Roy & Suman, 2011) and has outpaced overall higher education enrollments (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016). Online programs are designed and delivered in multiple ways to individuals, and these delivery mechanisms take advantage of the technological and pedagogical innovations that are now available to educational programs. These innovations include, but are not limited to, the utilization of the internet to provide online (distance learning), learning management systems to create virtual learning environments, the use of videos and images to support textual data, augmented and virtual reality, and the use of online communication tools to support both asynchronous and synchronous dialogue.

For several decades educators and researchers have noted the potential of changing our education system through the use of online education (Cercone, 2008; Garrison, 2011; Moore & Kearsley, 1996; Oliver, 2002). In 1996, Moore and Kearsley noted that distance education (separating students in space and potentially in time from their instructors) "portends significant changes in education and how it is organized" (p. 15) primarily as a result of providing access to those who could not have attended the traditional system due to their location, life circumstance, work schedule, etc. There are those who have gone further and envision a complete revolution in the educational system, such as Curtis Bonk (2009) who states that "Earth will become a learning plant" through the use of web technology. More recently the increased attention, both negative and positive, to massive open online courses (MOOCs; as cited in de Freitas, Morgan, & Gibson, 2015) have changed the focus of academic rhetoric to this new delivery approach that purports to deliver online courses, certifications, and programs at little to no cost to a global population.

At the surface these innovations seem to illustrate the increase of access to adult learners around the world, and indeed for those who are engaged in continuing their education the increase in choice is obvious. One would assume, with this evolution of the educational landscape, that research on who the online learner is and the impact of their ability to access education would have been undertaken and published within the academic literature, however, upon review of the literature, little has been done in this regard. This observation was the result of several years of research in online education where I looked to the literature to help build an online learner profile, realizing that no current or complete description existed; "[t]his situation carries considerable pedagogical implications for the design of online learning environments" (Dabbagh, 2007, p. 217).

Although little research has been done to examine who online learners are, or could potentially be, there is a wealth of research that examines the student experience once they enter a program (Chen, Lambert, & Guidry, 2010; Kauffman, 2015; Poelhuber & Anderson, 2011; Zimmerman, 2012). Within these research studies, students are superficially identified simply as online students, listed as a category (e.g., certificate students, undergraduate students, graduate students; Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016; EduConsillium, 2015), described generically as non-traditional students, or are described through descriptive statistics (e.g., gender, age, work status, geographic location; Dabbagh, 2007; del Valle & Duff, 2009).

The consequence of a research focus that examines a course, a program, an educational innovation, or intervention is that the focus is removed from what I believe was the initial focus of online learning - that of creating educational opportunities and enabling people who have yet to engage in higher educational studies. If we do not focus on how the design of an educational environment can enable adults to engage and be successful in post-secondary education then we will continue to mimic what we have always done, and instead of being innovative and perhaps revolutionary in our educational initiatives, we will simply duplicate our historic methods into a new modality. Although a clear profile of an online learner may not be a guarantee of success it would

significantly help administrators, teachers, and instructional designers understand (a) who is likely to participate in online leaning, (b) what factors or motivators contribute to a successful online learning experience, and (c) the potential barriers deterring some students from participating in or successfully completing an online course (Dabbagh, 2007, p. 217).

By not shifting at least part of the focus of online learning from within our courses, programs, or institutions to those adults who wish to engage in post-secondary educational activities, our research will never reflect the true demand for further post-secondary education and will continue to measure and evaluate only the demand for this that is currently being met (Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, 2011).

This focus on the current students within the learning environment does not provide an environment that facilitates the envisioning of changes to our educational system that would provide education for those who wish to learn, and instead continues to perpetuate a system for those already found within. This perpetuation prevents the recognition of those individuals that by context of their circumstance, gender, culture, or place within society, do not fit within the historical perspective that analytics and statistical descriptions provide.

Although online learning provides an enabling and accessible medium of education for adults across our globe, the focus of the institutions providing formal education seems to be firmly rooted within their perceived boundaries. "Universities... find distance education attractive since they can increase enrolments without increasing their physical plan requirements and they can reach out to audiences that would not otherwise be able to attend post-secondary education or who would not normally attend that particular institution" (del Valle & Duffy, 2009, p.129). Institutions are looking at efficiency and extending their market and the creation of new markets (del Valle & Duffy, 2009; Oliver, 2002), meaning that their focus is on their institution's financial health and not on the societal implications of providing education to our world's population. Oliver notes that this impacts not only their decision of what to place online but that "the bulk of online units tend to be based around very narrow instructional design models and tend to be a testament to the economic efficiency and marketing imperatives on which they are based" (2002, p. 35).

When an adult chooses to further their education, their perspective goes well beyond the boundaries of a course, program, institution, and can, given the advances of online offerings globally, expand to a global evaluation of what fits within their responsibilities and expectations as a member of their family, work, community, and society as a whole. When we examine and evaluate education, researchers and practitioners see the adults within their class, course, program, or institution only within their role as a student. This is not reflective of any adult's experience, which is composed of every decision we make as a member of our society, based on the myriad of responsibilities and choices we must make every day. To truly look beyond our conceptualized boundaries of student, instructor, and institution, researchers need to be able to recognize and capture those involved as more than students and certainly more than their statistical descriptions of demographics, courses, and grades.

The identified lack of understanding of the potential online learner and the implications to the design of online programming heavily influenced the design of this research project, by focusing on adults contemplating accessing online education as part or all of their education journey. This research was done within a specific geographic region - the province of Alberta, Canada - and captured their experience of deciding to engage in online learning. By capturing what adults consider before deciding to take online courses, we (instructors, instructional designers, program administrators, researchers, strategic planners, etc.) can begin to address the needs of these potential learners leading to the changes to our educational landscape that these technological advances can create.

The existence of online learning and potential students encompasses our planet; however, to respect the history, culture, and needs of each area, a study needs to clearly describe the participants that will represent the findings. This study examines adults from across the province of Alberta, Canada and reflects the county, the province, and the environment and culture Albertans live within.

Canada is the second largest nation in the world with a total area of 9,984,670 square km (Statistics Canada, 2005) and a large sparsely populated northern region, as the vast majority of Canada's population resides in the more habitable southern portion of the country. Canada is comprised of 10 provinces and three territories, and according to the Statistics Canada 2016 Census, Canada has a population of just over 35 million (Statistics Canada, 2017). It is a diverse, multi-cultural nation with over 200 languages identified in the 2011 Census (Statistics Canada, 2012) with a strong aboriginal population consisting of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, each with their own culture and language. According to Statistics Canada's 2011 census, 64.7% of the non-Aboriginal population (25 to 64 years) had some level of postsecondary qualification compared to 48.4% of the Aboriginal population (25 to 64 years). Within this group 26.5% of the non-Aboriginal population had a university degree compared to 9.8% of the Aboriginal population. (Statistics Canada, 2016).

It is difficult to look at a national perspective on education (past the generalized type of statistics provided by Statistics Canada) as Canada is the "only industrialized country without a federal office or department of education... [and] there is no clear mechanism for national policy development" (Shanahan & Jones, 2007, p. 32). As part of the Canadian constitution, each province (and territory) is given ownership of their educational systems (Government of Canada, 2017) and as such the federal government has no direct role in directing or shaping our education systems. In an attempt to create a national perspective, the federal government created the Canadian Learning Council in 2004, however, this is no longer locatable through electronic media. A second council (which may have been an offshoot of the 2004 council), the Canadian Council on Learning, dissolved in April 11, 2012 (voices-voix, 2012) and its website and resources have since disappeared. The final result is that there is no national organization that represents a national perspective on education. This has made research from a national perspective very difficult if not impossible to do.

To provide a Canadian context, I have pulled from two resources: EduConsillium's report on Online and Distance Education Capacity of Canadian Universities: Analysis and Review that was produced for Global Affairs Canada in 2015, as well as material found on the Canadian Virtual University (CVU-UVC) website (CVU-UVC, 2016a), both which offer a limited view of our post-secondary online learning environment. EduConsillium's work was focused primarily on attracting international students (Bates, 2016; EduConsillium, 2015) but did capture data analyzing Canada universities online and distance learning. CVU-UVC was founded in 2000 with two universities and initial funding from Industry Canada, with a mandate of increasing access to university education (CVU-UVC, 2016b). CVU-UVC has grown to include 11 Canadian universities and has reported that registrations are doubling each year since its inception (CVU-UVC, 2017) yet this organization represents only a fraction of Canada's post-secondary institutions. Recognizing these limitations, they do provide some data in regards to the current online environment in Canada.

Over the last few decades, online/distance education has grown; in Canada 93.15% of Canadian universities offered over 809 online programs and over 12,728 courses (EduConsillium, 2015). In fact, over 29% of the Canadian university student population took online courses during the 2014-2015 academic year (EduConsillium, 2015). Yet we "cannot be considered a leader in this field, as more than 20 countries invest about twice as much each year in their accredited online learning offerings" (EduConsillium, 2015, p. 3). CVU-UVC has noted that registrations in the online degree courses within their 11 members have exceeded 246,000 with 117,000 students within its 2000 courses (CVU-UVC, 2017). Although Canada has not focused efforts towards online learning there has been shown a strong and increasing demand for such offerings across the nation.

With the continuous advancements in technology and the expansion of utilization of technology enhanced learning within our educational programs, online learning has been made ubiquitous within our higher education institutions' long-term strategies. The primary strategic goals of these institutions is to use online courses to increase registration without increasing infrastructure costs (68.49 % of the institutions), to attract students from other regions or provinces in Canada (76.71% of the institutions), and to attract international students (53.42% of the institutions; EduConsillium, 2015). This institutional focus on financial issues reflects the overall findings of research in this area as noted previously (del Valle & Duffy, 2009; Oliver, 2002).

These two resources, although providing more than was available historically in regards to Canadian online learning, still do not focus on the learner themselves. Additionally, given that each province legislates and maintains their own education portfolio, there is no distinct Canadian education strategy as each province creates their own system based on its needs and circumstances.

Alberta has a population of just over 4 million people (Statistics Canada, 2017) and has a total area of 661,848 square kilometers (Statistics Canada, 2005). Alberta's economy has historically been highly resource based with a heavy emphasis on the oil and gas industry (Alberta Canada, n.d.). The educational system within Alberta is directed through two ministries with our post-secondary system under the Ministry of Innovation and Advanced Education and our K-12 system under the Ministry of Education. Alberta has 26 public post-secondary institutions located across the province including six universities, 11 colleges, two polytechnic institutions, two arts and culture institutions, and five independent institutions (Alberta Advanced Education, n.d.). Total enrolment in post-secondary institutions is 268,828 with 139,558 being full-time and 129,270 attending part-time (Advanced Education, 2016).

Until recently, the province of Alberta had a provincially funded consortium, eCampusAlberta (n.d.), which grew to represent all 26 of the provinces post-secondary institutions. Its vision was to "create a technology supported, lifelong learning environment that increases access to high quality online learning opportunities throughout Alberta" (para. 1), and its mission was to serve as a "province-wide advocate for increasing access to high quality learning opportunities... [t]ogether with its members, eCampusAlberta will facilitate the adoption of best practices in online learning to improve institutional resource effectiveness and serve as a catalyst for innovation and eLearning" (para. 2). Its mandate was "to research, develop and share best practices in online learning in order to assist member institutions, improve resource effectiveness and foster innovation and excellence in online learning in Alberta" (eCampusAlberta, n.d., para 3). After 14 years of continued growth in programming and registrations, eCampusAlberta ended on March 31, 2017 due to lack of continued funding. As a result, a growing and collaborative environment that did extend beyond a single institution ended with the closure of the consortium. The study on which this paper is based was made possible by eCampusAlberta, as they provided the conduit that allowed contact with the provincial population of adult learners.

With little research being undertaken focusing on Alberta's online learning environment and with no other body to access for data at a provincial level we can utilize historical data from a report based on a student survey undertaken by eCampusAlberta in the spring of 2013. This unpublished report noted that there was a positive response to eCampusAlberta and to online learning, as well as a desire for more online courses (Marles, 2013). This report focused primarily on demographics to describe the online student. Out of 900 responses 71% were female, 61% were over 25, 82% had taken courses or received certification within the post-secondary environment, and 44% worked full time. The validity of the study however is unknown, as nothing was reported on the process followed for this study.

The intent of this research was to begin to create a profile of the potential online student by moving beyond the limited role of student to that of any adult interested in online learning as a way to engage, either fully or in part, as part of their post-secondary studies. The choice to investigate adults within Alberta was motivated by a number of factors including, but not limited to, the lack of academic research done within this context; the acknowledgement that Alberta maintained its own education system; the characteristics of Alberta which are bounded by its history, location, and peoples; and the need to set a geographic boundary that the research could clearly describe and that could be set in a specific time and place. Additionally, I have been involved in the post-secondary environment for several decades and have heard many descriptions of an online learner, yet these descriptions are often based on the perspective of the individual and are rarely based on any evidence or supported by data or research.

This research engaged with adult learners across the province through the support of eCampusAlberta. At the time of the request for participation, eCampusAlberta had 16 of Alberta's 26 public institutions within the consortium (this grew to include all 26 institutions before it was dissolved in 2017; eCampusAlberta, 2014). To be able to plan, design, and deliver any online programming, the needs of the learners that will engage with these learning opportunities should be acknowledged (Cercone, 2008). According to Dick, Carey, and Carey (2001), design of learning needs to include a clear assessment of their attitudes, preferences, and skills. However, most post-secondary institutions create a program with a set of predetermined skills, expectations, and requirements which results in the identification of a student based on a set of prerequisite courses and grade levels. This creates a system where only those that fit within the predetermined institutional expectations are allowed to access the educational system. As Ken Robinson (2013) has noted, education is now focused on conformity and not on diversity and although speaking of the American's education system it does seem to reflect the educational environment across levels and location.

As a result of the current research focus in higher education this research project went beyond the institutional boundaries and contacted adults from across the province of Alberta who had shown interest in online education by engaging with eCampusAlberta and providing their information for further contact. The intention of this research was to capture the conceptions of these adults and present these conceptions regarding their decision to engage in online learning for part of their studies. The presentation of this data should inform all levels of post-secondary, from instructors and instructional designers to those engaged in strategic planning and research.

The research question that guided this project was "what are the commonalities and variations of the personal experience of adult learners (located in Alberta, Canada), focusing on their responsibilities of care, that led them to select online learning as part of their post-secondary coursework?" (Rasmussen, 2015, p. 23).

An adult must continually balance the multiple competing demands they have within their daily lives - from caring for themselves and their family to the responsibilities they have in their studies, work, home and their community (Rasmussen, 2013). Care, as defined by Tronto (1993) in her work with Fisher ( Toward a Feminist Theory of Care), is "[o]n the most general level, we suggest that caring be viewed as a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our 'world' so that we can live in it as well as possible" (p. 103).

The vastness of experiences that could be captured as a result of this research was seen as problematic, as a result a theoretical framework was selected to help provide a perspective that would still capture and help to elucidate the participants' conceptions in a meaningful way. By recognizing that "any decision to increase one's responsibilities by adding the responsibility of engaging in further education would be observable as part of one's practice of care" (Rasmussen, 2015). Given this recognition, the research utilized a practice of care framework based on Tronto's (1993) work on an ethic of care and adapted to provide a structure on which to base the research process. Figure 1 illustrates this framework.

| To acknowledge care | To observe and measure care |

| 1. Recognizing that care is needed | 1. Observe the recognition of care within a person's experience |

| 2. Taking responsibility and determining a response based on the recognition of care | 2. Observe and measure conflict of competing needs, responsibilities and of resource constraints |

| 3. Providing the care | 3. Observe the provision and receipt of care while remaining cognizant of cultural implications |

| By acknowledging this section the researcher may then focus the research process. | |

| By observing and measuring care as noted the researcher may then contain the scope of the research by a focus on the practice of care. | |

Figure 1. Practice of care framework. From The Ability to Access Post-Secondary Education: Adult Learners' Conceptions of Choosing Online Learning (p. 20), by K. Rasmussen, 2015, Lancaster University, UK. Copyright 2015 by Kari Rasmussen.

By utilizing this framework, the research had a lens through which it could perceive the study, allowing the research to focus on the lives of the adults as they choose to become learners while still capturing their other roles as a member of society. It provides a way to view the data during the analysis phase that again allows the research to embrace the multiple competing demands on an adult without a predetermined order of priority or importance. Finally, although this framework could be utilized to measure the care being provided, the measurement of the participants in the role of care-giver was out of the scope and intention of the project and therefore there was no evaluation on the care provided. However, this framework could be utilized to examine the experience within the boundaries of the institution to again recognize the practice of care and the provision of care, something that may be of interest to those looking at the overall health and wellness of the individuals involved within these boundaries.

This project utilizes a qualitative, phenomenographical approach to the design, data collection, analysis, and presentation of the results. Phenomenography "is a research methodology that aims to actually investigate the conceptions people have in relation to a particular phenomenon that give rise to their behaviours" (Pherali, 2011, p.7). Furthermore, phenomenography takes a second-order position that gives the voice to the participants, as it focuses on the variation of experience as described by the participants. "The world is only one world, a really existing world, which is experienced and understood in different ways by human beings... an experience is a relationship between object and subject, encompassing both" (Marton, 2000, p. 105). This approach allows the research to identify the variations of experience and provides the ability to investigate the participants' conceptualization of an event that could not be as clearly communicated by making statements about the event (Marton & Booth, 1997).

This design of this study is the integration of a qualitative, phenomenographical approach utilizing a practice of care framework. The design of this study is provided graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Research design for project. From The Ability to Access Post-Secondary Education: Adult Learners' Conceptions of Choosing Online Learning (p. 73), by K. Rasmussen, 2015, Lancaster University, UK. Copyright 2015 by Kari Rasmussen.

The interviews were designed based on the work of Bowden (2000); semi-structured interviews, focusing on open-ended questions were designed as the single source of data. A pilot interview was performed "both to provide an opportunity to develop the required skills but also to refine the planned questions" (Akerlind, Bowden & Green, 2005, p. 80-81). This pilot did alter the approach to the interview, creating a more conversational approach to the process, but did not impact the questions themselves. The results of the pilot interview were not included in the subsequent analysis.

Participants were selected through a purposeful sampling of learners (Suri, 2011) who showed interest, through eCampusAlberta, in engaging in online post-secondary studies. Participants had to be adults (18 years or older) and living in Alberta. Invitations to participate were emailed and subsequently 20 individuals were selected; one individual did not attend their interview which resulted in 19 total participants from across the province. Figure 3 shows the geographic disbursement of the participants

Figure 3. Participant distribution across the province of Alberta. From The Ability to Access Post-Secondary Education: Adult Learners' Conceptions of Choosing Online Learning (p. 84), by K. Rasmussen, 2015, Lancaster University, UK. Copyright 2015 by Kari Rasmussen.

All interviews were fully transcribed to capture both the message and context of the conversation by documenting not only the words but all aspects of the conversation (pauses, sighs, laughter, etc.). Categories of description (phenomenographical approach to the result of data analysis) were derived by coding the transcripts and involved an iterative process of moving from the participants as a whole, to a specific transcript, to a specific category, in order to ensure context was captured (Bowden, 2000; Prosser, 2000).

As the study utilized a theoretical framework (practice of care), this framework did have an effect on the coding process and the findings. This influence allowed for the coding process to address the personal conflicts experienced by the participants more explicitly then otherwise. As care is an emotion or set of thoughts they have to be acknowledged before they can be perceived.

After the categories of description were finalized further analysis between the final outcome space and the framework was performed to determine if there was alignment and to provide more depth in each category. This consistent focus provided grounding for the analysis and the ability to create a set of categories that would not have been perceptible without the framework.

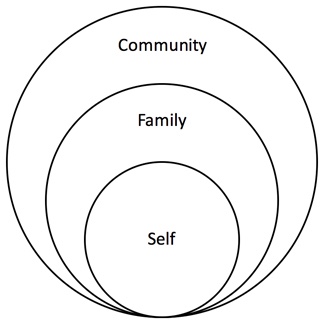

Phenomenographic studies result in an outcome space that shows the categories of description (commonalities) and their interrelationship (variation). Three categories of description were identified within the 19 participants' descriptions of their experience: the choice reflected my responsibilities to self, the choice reflected my responsibilities to my family, or the choice reflected my responsibilities to my community. The dimensions and interrelationship of these categories is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The outcome space - a visual representation of categories of description and their interrelationship. From The Ability to Access Post-Secondary Education: Adult Learners' Conceptions of Choosing Online Learning (p. 116), by K. Rasmussen, 2015, Lancaster University, UK. Copyright 2015 by Kari Rasmusen.

Responsibilities to self: these included learning needs, learning environment, financial security, independence, continuing to work, starting a career, maintaining a life/work balance, reaching their potential, not wanting to locate, and career needs.

Responsibilities to family: these included being a spouse, being a single mom, parents, meeting family expectations, grandparents, being a grandparent, family unit, and being a mom.

Responsibilities to community: these included making a difference, social work, geriatric care, focus of career, personal struggles, taking on an advocacy role, consideration of next steps, and striving to improve themselves.

All participants showed a consideration of responsibilities to self, some expanded their consideration to family, and of those who did consider their family, some then considered their impact on their community. This expansion of consideration aligned with the strength in which they articulated their identity in the previous or inner category of description; that is, those who had a strong sense of themselves would expand their consideration to family and those that strongly articulated a practice of care within their family showed consideration of their community. These results do not show a priority or linear approach to their decision to engage in further studies, for the practice of care is a continuous balancing act where all demands and responsibilities we have constantly impact our decisions (Tronto, 1993).

The foundation of this experience was the tie of these decisions to specific career aspirations; no participant within the study engaged in learning without a specific goal they wished to attain. These goals "showed a determination to better themselves or improve their life circumstance in some way" (Rasmussen, 2015, p. 147). No one spoke to taking online for exploration or general interest. Furthermore, each participant spoke about the responsibilities they had as an adult as main considerations for their choice to engage in online learning; their gender, their age, and their place in society were not within these descriptions unless they supported a role as a care-giver (spouse, grandparent, parent, etc.), yet it is these demographics that the literature focuses upon when analyzing learner populations. What impact would be possible if we expanded this description of a learner to a member of the society in which they live?

With the current emphasis on analytics and statistical information regarding our educational environment, our understanding and description of this environment is very narrow. If we expand our perspective to include a practice of care, in which we describe people as care-givers and care-receivers, we can move beyond the statistical description of our interaction with the world and as a result also recognize the complex and interwoven experience we have daily as members of our society. "The WORLD WILL LOOK DIFFERENT if we move care from its current peripheral location to a place near the center of human life" (Tronto, 1993, p. 101), and we can, by the nature of the framework utilized for this project, focus on the practice of care and its cultural implications if we so choose.

Online learning has continued to be an opportunity for transformation (Cercone, 2008; Garrison, 2011; Moore & Kearsley, 1996; Oliver, 2002), but it hasn't yet created the new environment we have been envisioning and discussing for years. In more recent years, MOOCs (de Freitas, Morgan, & Gibson, 2015) have gained a place in the academic literature and, given the number of individuals signing up for courses within the multiple MOOC platforms, the data analytics now available has pushed the focus of educational research in this area even more to the statistical description of the learning environment, learner, and the experience of the learner as they move through these online courses (Qu & Chen, 2015). To balance this focus on analytics we also need to continue examining the possibilities of online learning and the ability to transform our current systems. To do this it will be essential to move beyond our numerical descriptions of events. By examining those experiencing these environments through a practice of care lens with an approach that enables us to understand the mental constructs of these individuals through the use of research approaches like phenomenography, we can begin, perhaps again, to effectively "engage in discourse around opportunities and human potential" (Rasmussen, 2015, p. 161) while recognizing and respecting peoples' history, culture, and place within our world.

Advanced Education. (2016). Unique students by enrolment status, institution and sector for 2011-12 forward. Retrieved from http://advancededucation.alberta.ca/media/481815/ft-pt-unique-students-by-psi-and-sector.pdf

Akerlind, G., Bowden, J., & Green, P. (2005). Learning to do phenomenography: A reflective discussion. In J. Bowden & P. Green (Eds). Doing phenomenography (pp. 74-100). Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

Alberta Advanced Education. (n.d.). Publicly funded institutions. Retrieved from http://advancededucation.alberta.ca/post-secondary/institutions/public/

Alberta Canada. (n.d.). Alberta overview. Retrieved from http://www.albertacanada.com/business/alberta-overview.aspx

Allen, E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. (2016). Online report card: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group, LLC.

Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. (2011). Trends in higher education: Volume 1 - Enrolment. Ottawa, ON: AUCC. Retrieved from https://www.univcan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/trends-vol1-enrolment-june-2011.pdf

Bates, T. (2016, March 23). A national survey of university and online and distance learning in Canada [Blog post]. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources. Retrieved from https://www.tonybates.ca/2016/03/23/a-national-survey-of-university-online-and-distance-learning-in-canada/

Bowden, J. (2000). The nature of phenomenographic research. In J. Bowden & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 1-18). Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

Cercone, K. (2008). Characteristics of adult learners with implications for online learning design. AACE Journal, 16(2), 137-159. Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

Chen, P., Lambert, A., & Guidry, K. (2010). Engaging online learners: The impact of Web-based learning technology on college student engagement. Computers & Education, 54(4), 1222-1232. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.008

CVU-UVC. (2016a). Study with Canada's learning universities in online and distance education [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.cvu-uvc.ca

CVU-UVC. (2016b). Celebrating 15 years of leadership in online and distance education [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.cvu-uvc.ca/news-feed/Celebrating15YearsOfLeadership.php

CVU-UVC. (2017). Learning online is on the increase [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.cvu-uvc.ca/news-feed/Learningonlineisontheincrease.php

Dabbagh, N. (2007). The online learner: Characteristics and pedagogical implications. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 7(3). Retrieved from http://www.citejournal.org/vol7/iss3/general/article1.cfm

de Freitas, S., Morgan, J., & Gibson, D. (2015). Will MOOCs transform learning and teaching in higher education? Engagement and course retention in online learning provision. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 455-471.

Del Valle, R., & Duffy, T. (2009). Online learning: Learner characteristics and their approaches to managing learning. Instructional Science, 37(2), 129-149. doi: 10.1007/s11251-007-9039-0

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J. (2001). The systematic design of instruction (5th ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers Inc.

eCampusAlberta (n.d.). Vision, mission & mandate. Retrieved from http://ecampusalberta.ca/about-us/vision-mission-mandate

eCampusAlberta (2014). eCampusAlberta expands to help more students access online learning [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://ecampusalberta.ca/news/ecampusalberta-expands-help-more-students-access-online-learning

EduConsillium (2015). Online and distance education capacity of Canadian universities: Analysis and review. Retrieved from https://www.tonybates.ca/wp-content/uploads/ANALYSIS-AND-REVIEW-of-Canada-Distance-Education-2015-EN-final-1-1.pdf

Garrison, R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Government of Canada. (2017). Constitution acts, 1967 to 1982. Retrieved from http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-4.html

Kauffman, H. (2015). A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Research in Learning Technology, 23(1). doi: 10.3402/rlt.v23.26507

Li, Q., & Akins, M. (2004). Sixteen myths about online teaching and learning in higher education: Don't believe everything you hear. TechTrends, 49(4), 51-60. doi: 10.1007/BF02824111

Marles, C. (2013). eCampusAlberta spring 2013 student survey report V 2.3 (Unpublished report) eCampusAlberta: Calgary, Canada.

Marton, F. (2000). The structure of awareness. In J. Bowden & E. Walsh (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 102-116). Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

Marton, F., & Booth, S. (1997). Learning and awareness. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Moore, M., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A systems view. Belmont,CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Oliver, R. (2002). Winning the toss and electing to bat: Maximising the opportunities of online learning. In C. Rust (Ed.), Proceedings of the 9th improving student learning conference (pp. 21-37). Oxford: OCSLD.

Pherali, T. (2011). Phenomenography as a research strategy : Researching environmental conceptions. Sarrbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Poelhuber, B., & Anderson, T. (2011). Distance students' readiness for social media and collaboration. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(6), 102-125.

Prosser, M. (2000). Using phenomenographic research methodology in context of research in teaching and learning. In J. Bowden & E. Walsh, (Eds.), Phenomenography (pp. 34-46). Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

Qu, H., & Chen, Q. (2015). Visual analytics for MOOC data. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, 35(6), 69-75. doi: 10.1109/MCG.2015.137

Rasmussen, K. (2013). The choice of online education: Adult learners' Conceptions of choosing online learning (Research proposal). Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University, UK.

Rasmussen, K. (2015). The ability to access post-secondary education: Adult learners' conceptions of choosing online learning (Doctoral dissertation). Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University, UK.

Robinson, K. (2013). How to escape education's death valley (video). TED Talks Education. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_how_to_escape_education_s_death_valley?language=en

Roy, R., & Schumm, W. (2011). Audiences and providers of distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 25(4), 209-225. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2011.618312

Shanahan, T., & Jones, G. (2007). Shifting roles and approaches: Government coordination of post-secondary education in Canada, 1995-2006. Higher Education, Research & Development, 26(1), 31-43. doi: 10.1080/07294360601166794

Statistics Canada. (2005). Land and freshwater area, by province and territory [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/phys01-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2012). Language. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/video/video-lang-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada (2016). The educational attainment of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-012-x/99-012-x2011003_3-eng.cfm

Statistics Canada. (2017). Population and dwelling count highlight tables, 2016 census. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/population-eng.cfm

Suri, H. (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qualitative Research Journal, 11(2), 63-75.

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries. New York: Routledge.

Voices-voix. (2012). Canadian council on learning [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://voices-voix.ca/en/facts/profile/canadian-council-learning

Zimmerman, T. (2012). Exploring learner to content interaction as a success factor in online courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 162-165.

Looking Beyond Institutional Boundaries: Examining Adults' Experience of Choosing Online as Part of Their Post-Secondary Studies by Kari Rasmussen, PhD is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.