Figure 1. Technical setup for the online co-interpretive interviews.

Volume 20, Number 2

Katy Jordan

Institute of Educational Technology, The Open University, UK

Academics are increasingly encouraged to use social media in their professional lives. Social networking sites are one type of tool within this; the ability to connect with others through this medium may offer benefits in terms of reaching novel audiences, enhancing research impact, discovering collaborators, and drawing on a wider network of expertise and knowledge. However, little research has focused on the role of these sites in practice, and their relationship to academics’ formal roles and institutions. This paper presents an analysis of 18 interviews carried out with academics in order to discuss their online networks (at either Academia.edu or ResearchGate, and Twitter) and to understand the relationship between their online networks and formal academic identity. Several strategies underpinning academics’ use of the sites were identified, including: circumventing institutional constraints, extending academic space, finding a niche, promotion and impact, and academic freedom. These themes also provide a bridge between academic identity development online and institutional roles, with different priorities for engaging with online networks being associated with different career stages.

Keywords: digital identity, academic identity, digital scholarship, social networking sites, CMC, higher education

Social media is increasingly playing a role in the professional lives of academics. While this can include use of mainstream generic social media tools (such as Facebook and Twitter), platforms have also been developed specifically for academics. The two largest academic social networking sites (ASNS) are Academia.edu and ResearchGate (Van Noorden, 2014). However, the role that ASNS play is not well defined and despite the potential benefits of social media there has been little focus on how they are being used in practice, and the relationship between social media and the formal social context of academia.

Through analysis of the technical affordances of ASNS, the following main functions for academics have been identified: collaboration, dissemination and communication, document and information management, online persona and identity management, and impact measurement (Espinoza Vasquez & Caciedo Bastidas, 2015). All are tied to a formal academic identity to some extent, in two main ways. First, contrasting pressures and responsibilities at different stages of an academic career may prioritise different aspects of using the sites, and second, ASNS require profiles as a virtual representation of the self (Hogan & Wellman, 2014). In contrast to generic social media, where anonymity and pseudonymity are common (Ellison, 2013), the identity expressed through ASNS must be relatable to an academics’ offline persona in order to enjoy the benefits in their professional life.

Profile formats on ASNS has provided a ready source of data for exploring identity in terms of user characteristics at large scale. Demographic information required by profiles typically includes subject area, institution and job position, and may also include publication history, connections, and other information such as participation in discussions through the site. Web scraping and large-scale analysis of this information has been used to address questions about the extent of uptake of services by different demographic groups, and whether this reflects existing academic hierarchies.

Several such studies have focused upon Academia.edu as a data source (Almousa, 2011; Menendez, de Angeli & Menestrina, 2012; Thelwall & Kousha, 2013). In terms of disciplinary differences, Almousa (2011) reported that academics in Anthropology and Philosophy were more active than those in Chemistry or Computer Science. Thelwall and Kousha (2013) examined differences in terms of gender, as females have been shown to have an advantage in social media more generally, although female philosophers were found to have fewer Academia.edu profile views than males. This approach was extended to Law, History, and Computer Science, which revealed a mixed picture (Thelwall & Kousha, 2013).

In relation to job position, postdoctoral researchers emerged as the most active, uploading more material and following others (Almousa, 2011). Menendez et al. (2012) found that more senior academics were more proliferate in a range of profile characteristics than more junior academics. Across all three studies, graduate students were consistently found to have the lowest levels of use or profile completion (Almousa, 2011; Menendez et al., 2012; Thelwall & Kousha, 2013).

Menendez et al. (2012) also found that levels of use follow hierarchies in terms of university ranking and country development. Thelwall and Kousha (2015) follow up on the theme of whether ASNS preserve existing hierarchies in the context of ResearchGate. ResearchGate metrics were found to correlate with university ranking scores, and while some countries are disproportionately using the site (examples include Brazil and India), others are not (notably China and Russia; Thelwall & Kousha, 2015).

Although ASNS profiles are a ready source of demographic information, this may represent an impoverished view of academic identity online. Quantifying profile characteristics captures the product, but not the process, of identity construction and the dynamics that shape it. Academics are constrained in their definition of identity on ASNS as the profile fields are set by the technical design of the platform (Kimmons, 2014). The studies reviewed here focus upon a single platform, while academics are likely to construct their identity in different ways across the range of online tools that they use in relation to their academic practice (Veletsianos, 2016).

Large scale analysis of profiles identifies trends, but the academics’ own perspectives are required to understand the processes involved, and this is lacking in the context of ASNS. Considering the experiences of trainee teachers with generic social networking sites (SNS), Kimmons and Veletsianos (2014) discuss how their professional and personal identities are played out online, and the challenges of tensions between them. Manca and Ranieri (2016) surveyed academics’ levels of personal, professional, and teaching use of a range of social media platforms. ASNS use was found to be lower in relation to teaching compared to personal or professional uses. Teaching experience is reported to be related to the level of personal use of the sites, while age was correlated with professional use. Gender was found to be an important factor, with females demonstrating higher personal, professional, and teaching uses of ASNS (Manca & Ranieri, 2016).

Doctoral students and early career researchers (ECRs) have been identified as a group whose work and professional goals align well with the potential benefits of social media. Esposito (2014) focuses upon the role of social media in the transition from doctoral students to ECRs, drawing parallels with McAlpine and Akerlind’s concept of identity-trajectory (2010) as a way of conceptualising academic identity development. Academic identity-trajectory has three components; the intellectual, networking, and institutional strands. The intellectual strand “represents the contribution an individual has made and is making to a chosen intellectual field through scholarship”; the networking strand “represents the range of local, national and international networks an individual has been and is connected with”; and the institutional strand “represents each person’s relationships, responsibilities and resources wherever they are physically located” (McAlpine & Akerlind, 2010, p.139-143).

Social media and SNS may be at odds with formal institutional structures in a number of ways, such as not aligning with traditional indicators of academic worth and career progression (Fransman, 2013; Gruzd, Staves & Wilk, 2011), or carrying risks of challenging power dynamics and structures (Stewart, 2015). Stewart’s (2015) study of Twitter-active academics emphasises the development of academic identities and networks as individuals rather independent of formal institutions. The link between professional academic identity development facilitated by social media, mediated by different platforms, and the relationship between academic identity online and the existing literature on academic identity development more generally requires further clarification.

This study contributes to an understanding of the relationship between academics’ online networks and formal institutional roles. In doing so, the findings will help academics understand what they may gain from engaging with online social networks. The following research questions guided the study:

The study used a mixed methods social network analysis approach (Dominguez & Hollstein, 2014; Edwards, 2010), comprising co-interpretive online interviews to explore and discuss network structures with participants. Earlier phases of the project had used a survey and quantitative network analyses; the full study can be found in Jordan (2017).

Interview participants were invited to take part from a sample of 55 academics (stratified to include a range of job positions and subject areas) who had been included in the quantitative network analysis phase, which examined their ego-networks on ASNS (Academia.edu or ResearchGate) and Twitter (Jordan, 2019). The decision to sample pairs of platforms and include Twitter was informed by the findings of a recent large-scale survey undertaken by Nature Publishing Group. The survey data showed disciplinary preferences between Academia.edu and ResearchGate (Jordan & Weller, 2018). Participants’ Twitter networks were also included in the data collection, despite not being a specifically ASNS, as previous research highlighted that academics use it for a wider range of active scholarly purposes (Van Noorden, 2014). The sample of participants for interviews was stratified to include a range of job positions and subject areas (see Table 1). Two participants were invited per each combination of job position and subject area, for a total of 18 interviews. Note that the participants were assigned pseudonyms alphabetically in the order in which interviews were carried out; while the pseudonyms will be used when presenting quotes in the discussion, initials are given in the table (for example, H denotes “Harriet”).

Table 1

Pseudonym Initials Assigned to Interview Participants, Cross Tabulated by Job Position and Discipline

| Job position | |||||

| Professor | Lecturer | Researcher | Graduate student | ||

| Discipline | Humanities | O | N, P | C | I |

| Natural Sciences | H, M | A, D | G, K | E | |

| Social Sciences | L | F, R | Q, B | J | |

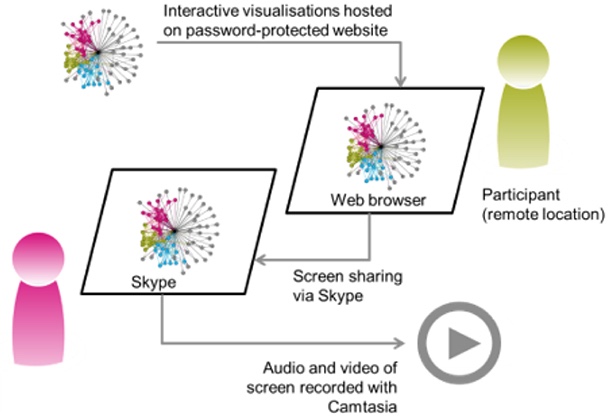

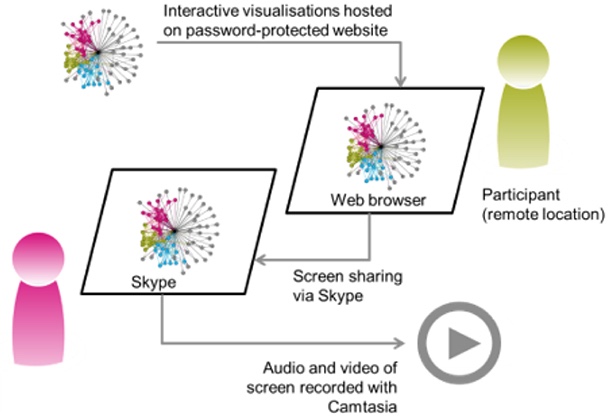

Participants’ networks had been analysed using Gephi (Bastian, Heymann, & Jacomy, 2009). The Sigma.js exporter (Hale, 2012) was used to create interactive versions of the networks which were shared with the participants ahead of the interviews. Each took place online via Skype; screen sharing was used so that both the interviewer and participant could see the network under discussion. Both audio and screen video were recorded during each interview. The technical setup of the interviews is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Technical setup for the online co-interpretive interviews.

The interviews were semi-structured (Wengraf, 2001), using a pre-planned interview schedule which was also shared with the participants in advance. The interviews were fully transcribed by the researcher to gain a greater level of familiarity with the data. The transcription data was used to annotate structure in the network graphs, and the discussions were analysed to understand instances where academics voiced explanations and personal reasons for their connections and use of the sites. The discussions were analysed using a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), undertaken using qualitative research analysis software (NVivo).

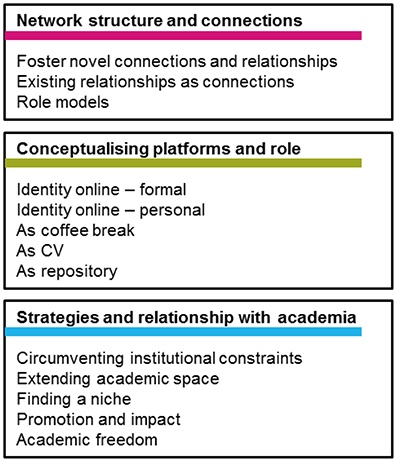

Open coding was first used to begin to identify common themes, following the participants’ own phrases and using constant comparison throughout the process. A sense of theoretical saturation (Morse, 2007) became apparent after the ninth interview during the analysis. During the second phase, open codes were combined into emergent categories, which were then reapplied to a new set of the transcripts to ensure consistency. Finally, the emergent categories underwent axial coding into themes (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). To assess the reliability of the analysis, the coding scheme was applied by a second coder to half the transcripts. Cohen’s Kappa was calculated and gave a value of 0.59 (Cohen, 1960), which can be considered a fair to good (0.40 to 0.75) level of agreement (Fleiss, 1981). The resulting coding scheme is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Emergent themes from the qualitative analysis.

The third level of the coding scheme (Figure 2), “strategies and relationship with academia,” is the focus of this paper. While the first two levels focused on the structural characteristics of participants’ networks and differences between how academics conceptualise different sites, the third level extended the analysis to why participants use the sites and how it fits with their formal academic roles. The themes include: circumventing institutional constraints, extending academic space, finding a niche, promotion and impact, and academic freedom. The results will be presented in two sections reflecting the research questions, and the themes will be discussed in detail with illustrative quotes.

The theme “circumventing institutional constraints” is directly related to the formal institution with which academics are affiliated, illustrating a strategic use of the tools to cultivate an online academic profile independent of controls on institutional web pages or repositories. The theme relates particularly to use of ASNS (Academia.edu or ResearchGate), rather than Twitter. For example, Harriet has an institutional webpage, but it is subject to editing restrictions: “I periodically do and don’t have editing rights over my [University] page, so I use my Academia.edu page as the place where my publications are available if somebody wants to find them.”

Institutions may be keen to populate their repositories with publications, but uploading is often via a gatekeeper. ASNS therefore provide the perception of increased personal control and efficiency. Nicola describes her experience uploading personal content:

It’s not ideal but I’m currently in the process at [University] of getting all my stuff on to [University]’s research portal which is so clunky... so because uni repositories can be so useless, I think Academia[.edu] can be valuable in that sense because no-one’s going and checking to see if you really are allowed to have that article PDF online.

“Extending academic space” relates to ways of using online networks to develop or maintain a profile as an academic beyond the boundaries (conceptually or physically) of their current role. Twitter was highlighted particularly in order to maintain research agendas and connections that are not a formal part of teaching-dominated roles. As Rachael explains, online identity is notably important to extend one’s professional network:

I worked at [University A] for six years as a fellow so I was a PhD student but I was also a faculty member, and so I felt very heavily connected to [University A]. [University B], although I’m a lecturer,... my online identity is actually quite distinct from my role at [University B].

For Pippa, Twitter has proved to be an effective way of maintaining a connection to her professional role and as a way of overcoming barriers in terms of time and physical location. In relation to part-time working, caring responsibilities, and the geographical location of her institution, Twitter provided a means for Pippa to maintain her objectives for all:

I feel slightly disconnected from my home university, and Twitter is a semi-substitute for that. There’s sort of meetings and training that I don’t go to at work, but I sort of have a sense of stuff that’s going on out there in the higher education world, from Twitter.

This theme also includes examples where academics have used online networks (particularly Twitter) in order to create multiple online identities, representing not only their personal identity, but those of their projects, groups, and departments. Isaac could not recall exactly how many Twitter identities he has, which include accounts related to personal interests, political satire accounts, and academic project accounts. Carol, David, and Oliver also highlight accounts that they manage or co-manage for academic projects. David uses Tweetdeck to manage several professional accounts and streams that he is responsible for, including his department’s Twitter feed, his research group, and the Twitter account for a specialist interest society group that he volunteers with.

The “extending academic space” theme also includes emerging practices around Twitter as a research site in itself. For example, Emily joined Twitter in 2011, as part of her doctoral research, to discover links to individuals and blogs from an otherwise hard to reach population. Kieran uses Twitter in a similar way, but adopts an observational role and is cautious about the potentially negative consequences of being drawn into online discussions. While this has been an integral part of Emily’s doctoral work, other participants also view Twitter as a research site but in less formal terms. For example, Nicola uses Twitter to monitor developments in the industry related to her research topic, and Pippa has used Twitter to monitor world events in real time, and crowdsourced photos for her book.

The idea of SNS playing an important role in constructing an academic identity came through very strongly, with notions of “finding a niche” being viewed as particularly important for doctoral students by academics at all levels. Now PhD students, Isaac and Jacob both started to cultivate their online identities during Master’s courses. Jacob explains:

I started using [Academia.edu] because... I just thought it would be interesting, finding out what other academics were doing, sharing my work a bit, 'cos when I started the [Master’s degree] that was when I started thinking about what research I really wanted to do, and where I wanted to place myself as an academic. So [a] part of that process is sort of identifying your niche, and letting people know that you’re there.

Reflecting on when they set up their ASNS and Twitter profiles, Kieran and Quentin (now a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer, respectively) also note that these activities were undertaken when they were still students. Quentin perceives that, increasingly, the need to form an online academic identity begins at the undergraduate level.

I’ve found there’s an increasing trend on Academia.edu of kind of people doing undergraduate degrees and Master’s degrees are using it, I think quite a lot of students they get to university, they get an Academia.edu profile and they look up people from the same institution, lecturers, or researchers, and they just kind of build their own connections that way so it’s quite interesting that it seems to have shifted further back along the career path and education.

Emily described her Academia.edu account as a “portable repository,” emphasising its role as a space which is defined but can travel with her. Although Emily does not intend to stay in academia post-doctorate, she is likely to keep using Twitter because she has created “a personal brand” there, although this may depend on her future employer:

It’s your personal brand, you are, it’s a very public way of saying these are the things I’m interested in and this is my perspective on them. You can tell very clearly the politics of someone if they use it in that way, and I think it really depends on where I work.

Post-doctorate, academic online networking takes a different role in negotiating interdisciplinary fields and transitions. For example, Carol moved from a Humanities-based field for her PhD into a Social Science-based field as a postdoctoral researcher. Her network structures include communities from both fields and her high ego betweenness centrality indicating that she is acting as a broker between otherwise disparate communities. While he remains in his home discipline of Geography, Kieran is looking to find different ways of focusing his work, for example through engaging with Science and Technology Studies, and he has consciously sought out connections in the field within his Academia.edu network. Postdoctoral researchers are still liminal in relation to formal academic structures, and online networks can provide a persistent space for hosting a formal academic identity. Nicola explains:

While I was on the job market... the uni didn’t have a good website and because I was temporary I certainly wasn’t getting much more than my name and photo on the website, no research portal or anything because I was just teaching staff, so Academia[.edu] was important then because at least if someone Googled me they would find me.

In relation to “promotion and impact,” the ability to track metrics adds to the appeal of ASNS. This is linked to mechanisms for promotion and perceived demonstrations of the value of academic work. The interviews suggest that this theme is of particular concern for mid-career academics, looking to secure permanent or more senior positions. Gillian describes how the act of uploading new publications to ResearchGate helps “to make myself searchable, REFable, that sort of thing.”

Promoting her work was a key motivation for Pippa in joining Academia.edu and Twitter, as she was in the process of writing a book and wanted to promote it through her online networks. She also wanted to be able to use evidence from the platforms as part of a promotion case. Pippa describes her use of Academia.edu:

I wanted to use it as part of a promotion application. I wanted to be able to say look, this is where my work’s read, and how interested people around the world are in my work, and then I’ve found the more general benefits of it.

While ASNS do readily provide metrics, whether ASNS or Twitter are actually more effective at disseminating research and achieving impact is not clear. For example, Lucy and Jacob hold contrasting views on the value of Twitter in this respect. Lucy explains that

I think Twitter is probably much less effective at disseminating my own research than ResearchGate and Academia.edu, so mainly Twitter for me is just about the transmission of mainly professional information.

While Jacob feels that

In the Social Sciences it is as valuable, and really as desirable, for a tweet to be read by a non-academic as it is to be read by an academic... so if I’m on Academia[.edu] and I write something like that, it’s like shouting into a cul-de-sac.

The “academic freedom” theme may also relate to differences in network structures observed according to job position, with professors and PhD students having the largest Twitter networks (Jordan, 2017). At the transition from PhD student to postdoctoral researcher (either within or outside of academia), participants indicated a perceived reduction in freedom to network. For example, Beth remarked that while active networking was viewed as being part of a PhD student’s experience, she doesn’t feel that networking is part of her role as a postdoctoral researcher working on another academic’s project. Jacob has always used Twitter in a personal capacity as well as professional; however, starting a teaching post in his department alongside finishing his PhD has impacted his views on tweeting.

Since I’ve felt myself in a position of responsibility, I’ve tried to be less weird, at least before 6pm, and I enforce that as a rule on myself, assuming that’s working hours. But I know a lot of people who have two accounts, a personal and a work account, or go one way or the other.

While awareness of Twitter as a public space, attendant potential hazards and practices to decide what should or shouldn’t be mentioned on the platform were referred to by the majority of participants, there were indications that more senior academics may feel more at ease expressing opinions, being more integrated into their professional communities. Frances explains that

I would also be a bit cautious about expressing a controversial opinion, but mostly because I don’t want to end up in the middle of some Twitter nastiness. But I doubt that that would ever happen because within my community it’s just people who know me... if they don’t know me, they’ll know someone who has worked with me.

The interviews uncovered a disciplinary element in terms of the types of communities which academics become part of on different platforms. While communities are more frequently defined by institutional relationships on ASNS, subject areas and specific research topics defined communities more frequently on Twitter (Jordan, 2017). The interviews support the notion of Twitter communities as being representative of the subject areas in which academics are embedded. This mirrors differentiation of academics’ identity between formal, hierarchy-preserving, and institutional-focused identity on institutional homepages (Hyland, 2011) and disciplinary-focused online identity through personal webpages (Hyland, 2013).

Results across all phases of the study give a stronger indication of differences in how online networks are used and conceptualised at different career stages. This illuminates how the three strands of identity-trajectory (intellectual, institutional, and networking; McAlpine & Akerlind, 2010) are reflected in academics’ professional use of social media, and extends and complements frameworks of social media use that have focused upon PhD students and ECRs (Esposito, 2014). The frequency of different codes according to job categories of interview participants are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2

Matrix Coding Query of Themes According to Job Position, Shown as a Percentage of Participants Within Each Job Position

| PhD student (n = 3) | Researcher (n = 5) | Lecturer (n = 6) | Professor (n = 4) | |

| 1.1 Foster novel connections and relationships | 67 | 60 | 33 | 100 |

| 1.2 Existing relationships as connections | 67 | 100 | 100 | 75 |

| 1.3 Role models | 33 | 20 | 50 | 50 |

| 2.1 Academic identity online - formal | 100 | 60 | 67 | 100 |

| 2.2 Academic identity online - personal | 100 | 40 | 67 | 100 |

| 2.3 As coffee break | 33 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| 2.4 As CV | 67 | 20 | 50 | 0 |

| 2.5 As repository | 67 | 20 | 17 | 75 |

| 3.1 Circumventing institutional constraints | 33 | 0 | 17 | 75 |

| 3.2 Extending academic space | 33 | 40 | 83 | 50 |

| 3.3 Finding a niche | 100 | 100 | 33 | 25 |

| 3.4 Promotion and impact | 33 | 20 | 50 | 25 |

| 3.5 Academic freedom | 67 | 40 | 50 | 50 |

The network analyses revealed differences according to platform in terms of job position. While their average network size on ASNS was the smallest compared to other groups, doctoral students have larger networks than mid-career academics (researchers or lecturers) on Twitter (Jordan, 2017). This may indicate that Twitter provides a more ready space for students to create online professional networks than ASNS.

In relation to understanding the processes behind network construction, the theme of “finding a niche” reflects the higher reciprocity and agreement within networks playing a role in career development. Codes relating to finding a niche were raised in interviews by all of the PhD students and researchers, in contrast to a third of lecturers and a quarter of professors. The importance of finding a niche and building an academic identity for doctoral students mirrors findings from Esposito (2015), who identified strategies in her study of doctoral students of weaving and splitting professional identities across different platforms, and choosing what to share online carefully. The present study reinforces this finding, and also extends it by finding that the issues persist further in academic careers too. Researchers often recalled starting their networks during their recent graduate studies, and their use has continued into their postdoctoral careers. Kieran describes his motivations for using social networking in graduate school:

I think [started using Twitter] must’ve been during my Master’s degree or the first year of my PhD... it was about that move to develop an online profile, 'cos I very much see my Twitter account as a professional thing, if you like, it’s a space for my academic identity.

All of the researchers included in the interview sample were postdoctoral researchers, having completed their doctorates in recent years, working on research projects, and not employed on permanent contracts. As such, researchers showed similarly high levels of agreement with survey items (Jordan & Weller, 2018) in relation to career development (discussed previously in relation to doctoral students), and is reflected in the interviews in a continued desire to find a niche, such as in Beth’s interview:

On Twitter people seem to specialise in particular things that they tweet about, and I am currently just sort of tweeting about this that and the other and not really anything in particular.... I need to find my niche.

The survey response and interviews show a slightly different character to “finding a niche” for researchers (Jordan & Weller, 2018). With a greater level of research experience behind them compared to doctoral students, promoting their research rather than themselves personally is viewed as more important at the post-doctorate level, with many researchers agreeing with the survey items “sharing authored content” and “raising the profile of your work in the research community.” It is also notable that while they share the need to find a niche and secure permanent jobs, this was not raised by doctoral students, which may reflect findings that doctoral students are reluctant to share research for a combination of reasons, including awareness of what is permitted by publishers and influenced by their supervisors’ views on the legitimacy of openness in scholarly practice (Carpenter, Wetheridge, & Smith, 2010). However, a perception that researchers face compromises in relation to their freedom to network and use social media was alluded to, through the “academic freedom” theme. Emily’s interview illustrates this:

There’s a lot more freedom at a university, and then being a student you get a lot more freedom again.... It’s your responsibility, you’re the one who’s putting the information out there, you’re the one who deals with the consequences.

The lecturers included in the sample held permanent academic appointments, two of the six being in senior positions (Frances and Pippa). Lecturers still agreed with two of the careers-related survey items already discussed. Additionally, lecturers and professors showed a greater level of agreement with the survey item “I use social networking sites to support my teaching activities” (Jordan & Weller, 2018). In the interviews, “promotion and impact” and “extending academic space” were both most prevalent in the lecturers’ category. The interviews explain that these are priorities for lecturers, in order to maintain an active profile as a researcher in the face of heavy teaching loads.

The theme of “circumventing institutional constraints” was a key motivation for professors to use ASNS. This was frequently borne out of a desire to improve access and dissemination to their research publications, and as Lucy describes, is coupled with restrictions on the speed, ease, and criteria for depositing items in their institutional repositories.

It is a little bit slower to get papers up on the institutional repository, particularly now with the new REF guidelines that everybody has to be open access.... With ResearchGate I can get a paper up there within seconds; with our institutional repository, it may be days, weeks, [or] months.

Through co-interpretive interviews around their social network structures on two of the main types of social media platforms used professionally by academics, this study has provided an enhanced understanding of the roles that online networks can play in relation to formal academic identities. Furthermore, it also illuminates how the roles of online networks can be subject to different pressures and priorities in relation to different academic career stages. The findings advance research in this field in two main ways: first, by providing further empirical evidence of how digital scholarship is enacted in practice, through the particular technological lens of SNS (practices associated with ASNS not having been examined by existing studies); and second, by examining the reasons and strategies behind academics’ use of SNS to bridge the gap between their online identities and formal institutional roles.

In addressing the first research question, five themes were identified in relation to how and why academics developed and explained their online network structures in relation to their roles as academics. The five themes included circumventing institutional constraints, extending academic space, finding a niche, promotion and impact, and academic freedom. The themes build upon previous work on academics’ use of Twitter (Ahmad Kharman Shah, 2015) and the purposes for which academics use ASNS and Twitter (Van Noorden, 2014). The strategic themes identified here present a level of abstraction above these individual practices as to why academics use online networks in the ways that they do and is of practical value to academics who do not currently use social media in their professional lives.

The second question, which guided the study, concerned whether the structure and role of online networks showed different characteristics according to academic career trajectories. The benefits of online networking are frequently cast as being of particular value to more ECRs, while the significance for more senior academics remains under explored. Conversely, the social network structures fostered by ASNS favour existing hierarchies (Hoffmann, Lutz, & Meckel, 2015; Jordan, 2014), and academic seniority may be related to levels and purposes of use of social media platforms (Manca & Ranieri, 2016). The results here provide further detail and insight into the role online networks play at different career stages, which has both practical implications and furthers theoretical links with academic identity-trajectory as expressed online. Given the embeddedness of the more senior academics within professional subject communities and desire for academics to follow role models, it is important for the benefits to be examined across whole career trajectories. This will enable academics at any career stage to make better informed decisions about their adoption of social media and give ECRs and students a wider range of academic role models, to make further key connections within professional communities explicit.

The three strands of identity-trajectory (McAlpine & Akerlind, 2010) provides a way of conceptualising the role of online networks in relation to academic work. The networking strand is explicitly related to the perceived use of doctoral students in relation to network building and actively seeking connections to others within their field. Researchers leverage the intellectual strand through their use of the sites to promote the profile of their research and experience. Aware that maintaining an active profile as a researcher is key to further promotion within the academy but at odds with teaching-heavy roles, lecturers exploit their networks in order to do so, drawing upon their resources accrued through existing networking and overcoming barriers created by the institutional strand of their identity. The role of professors is interesting because although the size and embeddedness of their position within networks reflects an accomplished networking strand, their use of the sites is in contrast with the other categories. Despite being more secure in their formal positions within home institutions, professors are not empowered to freely control their online identity through their institutions and use of online networks (particularly ASNS) provides a way of circumventing this, inflecting the institutional strand through an online lens.

While the analysis extends and complements previous work that has focused upon doctoral students and ECRs, there are also some limitations due to the practical constraints of the sample. In order to ensure that a range of positions across academic career trajectories were represented, the sampling strategy focused upon those which fell into particular categories of job position (doctoral students, researchers, lecturers, and professors). This purposefully excluded potential participants who did not fit within these categories, such as para-academics, and those between formal academic roles and institutional affiliations. Online networks could be of greater importance to academics who support multiple identities in this sense (such as being a lecturer and doctoral student at the same time), (Bennett & Folley, 2014). Further follow-up work with academics working outside of formal academic roles and beyond the higher educational institutions in the UK context would be valuable.

The qualitative approach used here was exploratory in nature and provided insight into the nuanced ways in which academics’ online networks relate to formal identity trajectory. While measures were taken to ensure validity of the study, the sample is relatively small. A confirmatory, survey-based study could be undertaken to build upon the study and test the results within a larger sample. Considering multiple platforms (ASNS and Twitter) is also both a strength and limitation of the present study. Further work is currently underway to explore how academic identity is expressed across a larger sample of major social media sites, including generic platforms such as Facebook and LinkedIn (Jordan, 2018).

Ahmad Kharman Shah, N. (2015). Factors influencing academics’ adoption and use of Twitter in UK Higher Education (Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield, UK). Retrieved from http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/11505

Almousa, O. (2011, December 6-8). Users' classification and usage-pattern identification in academic social networks. Paper presented at the 2011 IEEE Jordan conference on Applied Electrical Engineering and Computing Technologies (AEECT), Amman, Jordan. doi: 10.1109/AEECT.2011.6132525

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (pp. 361-362). Palo Alto, USA: AAAI.

Bennett, L., & Folley, S. (2014). A tale of two doctoral students: Social media tools and hybridised identities, Research in Learning Technology, 22, 1-10. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v22.23791

Carpenter, J. Wetheridge, L., & Smith, N. (2010). Researchers of tomorrow: Annual report 2009-2010, London: British Library/JISC. Retrieved from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/researchers-of-tomorrow

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37-46. doi: 10.1177/001316446002000104

Dominguez, S. & Hollstein, B. (Eds.). (2014). Mixed methods social networks research: Design and application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, G. (2010). Mixed-method approaches to social network analysis (Discussion Paper ID 842). Southampton: National Centre for Research Methods. Retrieved from http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/842/

Ellison, N. (2013). Future identities: Changing identities in the UK - the next 10 years. London: Government Office for Science. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/275752/13-505-social-media-and-identity.pdf

Espinoza Vasquez, F.K., & Caicedo Bastidas, C.E. (2015). Academic social networking sites: A comparative analysis of their services and tools. Paper presented at iConference 2015, Newport Beach, USA. Retrieved from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/73715/380_ready.pdf?sequence=2

Esposito, A. (2014). The transition 'from student to researcher’ in the digital age: Exploring the affordances of emerging ecologies of the PhD e-researchers. (Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10609/41741

Esposito, A. (2015, September). PhD researchers using social media: Trajectories of academic identities. Presentation at academic identity in the digital university: current trends and future challenges. The Society for Research in Higher Education, London, UK.

Fleiss, J.L. (1981). Statistical methods for rates and proportions (2nd ed). New York: John Wiley.

Fransman, J. (2013). Becoming academic in the digital age: representations of academic identity in the online profiles of early career researchers. London: Society for Research in Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.srhe.ac.uk/downloads/FRANSMAN_Final_Report.pdf

Gruzd, A., Staves, K., & Wilk, A. (2011) Tenure and promotion in the age of online social media. Paper presented at the Association for Information Science and Technology (ASIS&T 2011) Annual Meeting, New Orleans, USA. doi: 10.1002/meet.2011.14504801154

Hale, S.A. (2012, November 15). Build your own interactive network (Blog post). Interactive Visualizations. Retrieved from http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/vis/?p=191

Hoffmann, C.P., Lutz, C., & Meckel, M. (2015) A relational altmetric? Network centrality on ResearchGate as an indicator of scientific impact. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(4), 765-775. doi: 10.1002/asi.23423

Hogan, B., & Wellman, B. (2014). The relational self-portrait: Selfies meet social networks. In M. Graham & W.H. Dutton (Eds.) Society & the Internet: How networks of information and communication are changing our lives (pp. 53-66). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyland, K. (2011). The presentation of self in scholarly life: Identity and marginalization in academic homepages. English for Specific Purposes, 30(4), 286-297. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2011.04.004

Hyland, K. (2013). Individuality or conformity? Identity in personal and university homepages. Computers & Composition, 29(4), 309-322. doi: 10.1016/j.compcom.2012.10.002

Jordan, K. (2014). Academics and their online networks: Exploring the role of academic social networking sites. First Monday, 19(11). Retrieved from https://firstmonday.org/article/view/4937/4159

Jordan, K. (2017). Understanding the structure and role of academics’ ego-networks on social networking sites (Doctoral dissertation, The Open University, UK). Retrieved from http://oro.open.ac.uk/48259/

Jordan, K. (2018, December 5-7). Networked selves and networked publics in academia: Exploring academic online identity through sharing on social media platforms. Paper presented at the Annual Society for Research in Higher Education Conference, Newport, Wales. Retrieved from http://oro.open.ac.uk/58548/

Jordan, K. (2019). Separating and merging professional and personal selves online: the structure and processes which shape academics’ ego-networks on academic social networking sites and Twitter. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, early view. doi: 10.1002/asi.24170

Jordan, K., & Weller, M. (2018) Communication, collaboration and identity: Factor analysis of academics’ perceptions of online networking. Research in Learning Technology, 26, 2013. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v26.2013

Kimmons, R. (2014). Social networking sites, literacy, and the authentic identity problem. TechTrends, 58(2), 93-98. doi: 10.1007/s11528-014-0740-y

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2014). The fragmented educator 2.0: Social networking sites, acceptable identity fragments, and the identity constellation. Computers & Education, 72, 292-301. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.12.001

Manca, S., & Ranieri, M. (2016) “Yes for sharing, no for teaching!”: Social Media in academic practices. The Internet and Higher Education, 29, 63-74. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.12.004

McAlpine, L., & Akerlind, G.S. (2010). Becoming an academic: International perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Menendez, M., de Angeli, A., & Menestrina, Z. (2012). Exploring the virtual space of academia. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Design of Cooperative Systems (pp. 49-62). London: Springer-Verlag.

Morse, J. (2007). Theoretical saturation. In M.S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T.F. Liao (Eds.) The SAGE encyclopaedia of social science research methods (pp. 1122-1123). London: SAGE.

Stewart, B. (2015). Scholarship in abundance: Influence, engagement, and attention in scholarly networks. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, Canada). Retrieved from http://bonstewart.com/Scholarship_in_Abundance.pdf

Strauss A.L., & Corbin J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: SAGE.

Thelwall, M., & Kousha, K. (2013). Academia.edu: Social network or academic network? Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(4), 721-731. doi: 10.1002/asi.23038

Thelwall, M., & Kousha, K. (2015) ResearchGate: Disseminating, communicating and measuring scholarship? Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(5), 876-889. doi: 10.1002/asi.23236

Van Noorden, R. (2014). Online collaboration: Scientists and the social network, Nature, 512(7513). Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/news/onlinecollaboration-scientists-and-the-social-network-1.15711

Veletsianos, G. (2016). Social media in education: Networked scholars. New York: Routledge.

Wengraf, T. (2001). Qualitative research interviewing. London: SAGE.

From Finding a Niche to Circumventing Institutional Constraints: Examining the Links Between Academics’ Online Networking, Institutional Roles, and Identity-Trajectory by Katy Jordan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.