Figure 1. Generations of ODL in Turkey, adapted from “The Past, Present and Future of the Distance Education in Turkey” by A. Bozkurt, 2017, Açık Öğretim Uygulamaları ve Araştırmaları Dergisi, 3, p. 88. CC BY-NC-SA.

Volume 20, Number 4

Aras Bozkurt

Anadolu University and University of South Africa

Open and Distance Learning (ODL) has a long history, one marked by the emergence of open universities, which was a critical development in the ecology of openness. Open universities have taken on significant local and global roles within the framework of meeting the needs of their respective regions of influence, and as such, their roles have evolved over time. Against this background, the purpose of this research is to explore the open university phenomenon by examining the case of Anadolu University in Turkey, a mega university that has transformed into what is now a giga university. More specifically, the research first looks at openness in education and how the concept itself has led to the emergence of open universities, before turning attention to Anadolu University, which is a dual-mode, state university with around 3 million enrolled students. Other issues that are addressed as part of this research include the rise of ODL and how it positioned itself within Turkish higher education; the historical development of Anadolu University and its massiveness, in terms of student numbers and services provided; local and global ODL practices; learner profiles, learning materials and spaces; exams and assessment and evaluation processes; learner support services, and Anadolu University's contribution, as an open university, to the field of ODL. The research shows that as an open university, Anadolu University has narrowed the information gap and digital divide, has enhanced equality of opportunity in education, and has provided lifelong learning opportunities. More importantly, as an institution that has gone beyond the conventional understanding of an open university, Anadolu University serves as a catalyst of change and innovation in its emergence as a role model for other higher education institutions. The following recommendations were able to be developed from the examinations of this study: (1) develop a definition of “openness” based on the changing paradigms of the 21st century and online learning, (2) enter into national and international collaborations between open universities, (3) adopt culturally relevant open pedagogies, (4) develop and design heutagogy-based curricula, and (5) unbundle ODL services in mega and giga universities.

Keywords: open university, open and distance learning, distance education, Turkey, Anadolu University

According to the visions and missions at the heart of the openness philosophy, open universities are rooted in the idea that education is a basic human right, that teaching and learning need to be democratized, that equity in education needs to be facilitated, and social justice improved. Though being perceived with great skepticism at first, over time, open universities have proved legitimacy, growing into mega and giga universities, and are now considered a part of mainstream education. While open universities have served to support universal values, the models and the way they adapt to change can differ depending on the specific society or region in which they operate. In this regard, this paper looks at open universities within the Turkish context by examining the case of Anadolu University, its historical development in the Turkish educational system and its appearance first as a mega university and then as a giga university.

Openness in education is more than an approach; rather, it is a philosophy with multiple roots, faces, and names, which views knowledge as a public good, upholds the need for equity in education, and has universal values as its core. As a philosophy, it has influenced how education is formed and delivered, and its roots can be traced back to the early period of human history. However, despite its long history, there has never been a precise definition provided on what openness in education means.

Historically, the term openness resists formal definition. The concepts underpinning the term can be very fluid in meaning and often only make sense when situated within a given context. Further, its use can become very ideological and political. The term open invokes in many an instant recognition of certain concepts and vague notions of certain values but becomes slippery and even dangerous when attempts are made to establish a common definition or to narrow the term's field of use. Efforts to define openness have often, although not exclusively, taken one or some combination of three general approaches. These include grounding openness in historical accounts of related movements and events; philosophically or conceptually seating openness as the underpinning ideal of a given context; and operationally negotiating openness in practical contexts. (Baker, 2017, p. 130)

In related literature, it can be seen that openness in education has been defined under numerous forms, including open learning, open teaching, open education, open source software, open access, open educational resources, open educational practices, open scholarship, OpenCourseWare, and massive open online courses, all of which are some of the more commonly mentioned forms; yet, the idea of openness is not limited to these concepts alone (Peter & Deimann, 2013; Peters, 2008; Smith & Seward, 2017; Pomerantz & Peek, 2016; Tait, 2018a). The related literature also shows that openness is not a fixed term but rather, a term that has had many interpretations, which have changed over the course of time and in different territories (Bozkurt, 2019; Harris, 1987; Hug, 2017). In the case of Turkey, openness in education can be defined as easy access to educational opportunities, with multiple entry points, no or low monetary costs, flexible learning processes, and where the focus is on independence in time and place.

Openness in education actually existed long before teaching and learning became comprehensively institutionalized (Bozkurt, Koseoglu, & Singh, 2019; Peter & Deimann, 2013; Peters, 2008), having emerged as an organized form of learning, through certain visionary efforts, following educational developments in the 1700s and 1800s (Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, & Zvacek, 2011; Verduin & Clark, 1991). Over the long history of openness in education, the Open University of United Kingdom (OUUK) qualifies as the best-known example of an open university to have adopted an institutionalized system view and to present certain ideological roots of openness. The foundation of OUUK served to inspire, as a model to adopt, many other higher education institutions across the world.

Open universities have evolved over the course of different generations. In the first generation, education was delivered in the form of correspondence; in the second generation, education was included the use of broadcast radio and television; in the third generation, education was offered through the creation of open universities; in the fourth generation, teleconferencing was incorporated into education; and finally, in the fifth and current generation, the Internet and Web are prominent and important considerations for the delivery of education (Moore & Kearsley, 2012). Further examination of these developments shows that while the third generation represents a system view, the other generations originated from advancements in information and communication technologies (ICT). It soon became apparent that there was a need to address certain critical factors associated with the emergence of open universities. For instance, once open and distance education became a part of mainstream education, new organizational policies and strategies for delivering educational content to learners, who were separated from instructors in time and space, were required. Along with the advancements in educational technologies, experimental studies that were conducted at the time shaped the educational perspectives (pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy) that eventually led to the emergence of open universities.

The ideas governing open learning and open universities are inspired by critical pedagogy (Peters, 2008) and have served to mitigate race-based inequalities, social and economic inequalities (Taylor, 1990), and language and cultural barriers (Van den Branden & Lambert, 1999). Moreover, these ideas have further served to increase the democratization of education and the redistribution of wealth (Taylor, 1990) and to facilitate social justice (Rumble, 2007; Tait, 2008, 2013).

In addition to the above benefits, open universities can be regarded as an innovation in higher education (Shale, 1997) and as a change agent, insofar as they introduced the manner in which innovation can be integrated into learning processes (Van den Branden & Lambert, 1999). In this context, it can be suggested that ICT and educational technologies have had critical roles and been pivotal drivers (Smith, 2005) for open universities in delivering an effective and efficient learning process and in “overcoming social inequity and the tyranny of distance” (Latchem, Abdullah, & Xingfu, 1999, p. 103). However, it is also important to note that, although the above-mentioned functions of open universities are salient, the roles and purposes of open universities have changed in line with paradigm shifts, and “what remains constant is the development function” (Tait, 2008, p. 93); therefore, it would be helpful to “define the purposes of an open university in this way” (Tait, 2008, p. 93).

Based on the above stated information, the purpose of this study is to discuss the development of open universities from the perspective of Turkey, focusing specifically on the case of Anadolu University. In doing this, the study intends to contribute to the existing literature and to gain a better understanding of the world of open universities, which is complex in nature and operates differently according to the changing needs of the societies across the world.

To achieve this stated purpose, the study adopted a traditional literature review methodology, an approach generally used to reinterpret, interconnect (Baumeister & Leary, 1997), summarize, synthesize, draw conclusions, identify research gaps on scattered pieces of knowledge, and provide suggestions for future research directions (Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008). The data were collected via document analysis (Bowen, 2009), aided in part by content analysis (Berelson, 1952), to attain synthesis of research on one of the open universities: Anadolu University.

This study presents up-to-date information about a unique open university case, Anadolu University, with the hope of contributing to the related literature. However, the study did have some limitations. First, the results of the study provide an in-depth understanding of only one open university and therefore cannot be generalizable. Second, the researcher is currently a member of Anadolu University, which possibly makes his interpretations fail, to a certain extent, to satisfy the objectivity.

After years of hard-fought wars, Turkey gained independence and declared itself a republic in 1923. However, as a country that lost much of its educated population as a result of the long-waged wars, education became one of the primary areas of reform in order to rebuild the country.

ODL has a long history in Turkey and can be examined in four distinct generations (Figure 1): the first generation covers the period of 1923-1955 and involved discussions and suggestions; the second generation covers the period of 1956-1975 and involved distance education being carried out in the form of correspondence (1956-1975); the third generation covers the period of 1976-1995 and involved distance education being conducted through the use of audio-visual tools (1976-1995); and finally, the fourth generation covers the period of 1996-present and involves the use of ICT-based applications (Bozkurt, 2017).

Figure 1. Generations of ODL in Turkey, adapted from “The Past, Present and Future of the Distance Education in Turkey” by A. Bozkurt, 2017, Açık Öğretim Uygulamaları ve Araştırmaları Dergisi, 3, p. 88. CC BY-NC-SA.

One of the first and most significant contributions to the development of ODL was made by John Dewey in 1924, just a year after Turkey declared itself a republic. Dewey's suggestions in the Report and Recommendation upon Turkish Education (Dewey, Boydston, & Ross, 1983) guided and shaped many of the educational practices in Turkey, including ODL (Boydston, 2008), which Dewey recommended being in the form of correspondence education: “(I)n-service teachers there should be for teachers in service correspondence courses. These might be conducted either by the Ministry of Public Instruction or by a normal school” (Dewey et al., 1983, p. 9). However, despite these visionary suggestions, the remaining 58 years saw many failed attempts to actually put ODL into practice.

According to 2018 data, Turkey has a population of 80 million, with the median age being 32 (Table 1; Turkish Statistical Institute, 2018). With the high youth population, there is a high demand for higher education (Askar, 2005; Cekerol, 2012; Geray, 2007; Ozkul, 2001). The combination of the continuing high demand, socio-economic factors (Berberoğlu, 2015; Kilinç, Yazici, Gunsoy, & Gunsoy, 2016; Latchem, Özkul, Aydin, & Mutlu, 2006; Gursoy, 2005), and the opportunities provided by ICT have resulted in the adoption of ODL and open universities in countries like Turkey, where there is a strong mass demand for higher education (Demiray, 2012), as a solution to capacity problems in higher education (Askar, 2005; Cekerol, 2012).

Table 1

Turkey's 2018 Population Statistics

Note. Adapted from “Basic statistics: Population and demography” by Turkish Statistical Institute, 2018 (http://www.tuik.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist). In the public domain.

Student numbers at the K-12 educational level further justify the demand for higher education. Accordingly, there is a total of 17,319,433 students at the K-12 level, which constitutes around 20% of the overall population. Among all these students, 5,513,731 attend traditional high school, while more interestingly, 1,287,249 attend high school through open education, which could be considered an indicator of the potential ODL has in Turkey (Turkish National Ministry of Education, 2018) and further demonstrates that ODL has an established tradition in the Turkish Education System (Askar, 2005; Selvi, 2006).

According to 2018 data, 2,322,421 students completed a university entrance exam, of which 43% had just graduated high school while 57% had graduated from high school at an earlier time. Among these applicants, only 910,680 (associate programs: 436.904; bachelor programs: 473.776) achieved scores high enough to be placed in universities (Turkish Student Assessment, Selection, and Placement Center, 2018a); and once graduated, the students in ODL programs are able to obtain academically equivalent degrees (Askar, 2005).

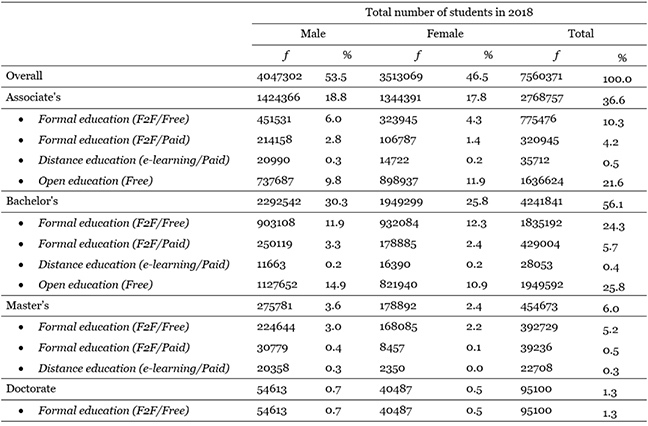

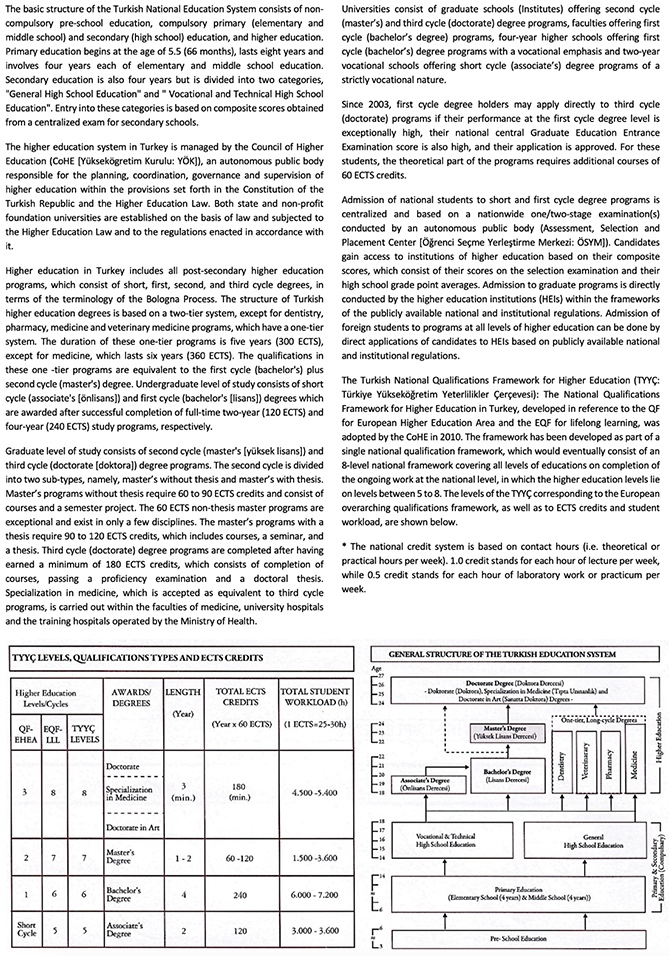

The Turkish education system consists of pre-school education, primary education, secondary education, and higher education with a slightly changing structure from its counterparts (see Appendix A). According to the Turkish Council of Higher Education (CoHE; 2018), there are around 7.5 million students in Turkish higher education system, a figure that constitutes approximately 10% of the overall population in Turkey (around 80 million) in 2018 (Table 2). Furthermore, the 3.5 million ODL students constitute around 50% of the overall higher education population, or 4% of the overall country population.

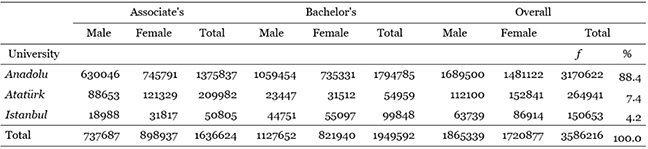

A major distinction in Turkish higher education is the legal definition of Open Education and Distance Education. Accordingly, open education offers open admissions with minimal entry requirements and flexible learning opportunities, whereby learning is self-paced, attendance is not required, learners are highly independent in time and space, and learning materials and spaces can be offline and/or online. On the other hand, distance education offers partly flexible admissions, whereby students are expected to meet predefined entry requirements and pay for and attend online courses that are delivered in online spaces with online materials. Moreover, open education can currently be delivered by only three dual-mode state universities (Anadolu, Atatürk, and İstanbul Universities; see Table 3), whereas distance education can be delivered by private or state universities.

Table 2

2018 Turkish Higher Education Statistics

Note. Adapted from “Higher education statistics” by CoHE, 2018 (https://istatistik.yok.gov.tr/). In the public domain.

In Turkish higher education, open universities can deliver ODL only for associate's and bachelor's degrees, and they are offered by only three state universities (Anadolu, Atatürk, and İstanbul Universities; Table 3). Students in Turkey gain access to institutions of higher education based on their composite scores, which consist of school grade point averages and the scores obtained on the central selection examination organized by the Turkish Student Assessment, Selection and Placement Center, an autonomous public body (Turkish Student Assessment, Selection and Placement Center, 2018b).

For enrollment in Anadolu University Open Education Faculty, students can benefit from different entry points. Accordingly, students are eligible to enroll by either (a) getting a minimum score on the central selection examination, (b) getting a sufficient score on the vertical transfer examination, (c) gaining the right to enroll through lateral transfer, or (d) being already enrolled in or graduated from a higher education program. In other words, there are multiple entry points to access higher education through the Anadolu University, Open Education Faculty. As can be seen in Table 3, in terms of enrolled number of students, Anadolu University is the leading university offering ODL (Appendix B shows enrolled student numbers according to level of study).

Table 3

Open Universities in Turkey and Their Student Numbers by 2018

Note. Adapted from “Higher education statistics” by CoHE, 2018 (https://istatistik.yok.gov.tr/). In the public domain.

Yılmaz Büyükerşen, the founder of ODL in Turkey, first became inspired in open universities following his 1966 visit to the United Kingdom. At this time, discussions were beginning in the United Kingdom around the idea of an open university as a model for delivering education to learners who demanded knowledge in a less traditional and more flexible way. However, Büyükerşen faced great struggles to convince policy makers that education could be delivered through ODL (Büyükerşen, 2009). It was not until 1981, after many failed attempts and a great deal of effort, that Anadolu University, Open Education Faculty, was legally defined as an open university, and in 1982, it began to deliver education through ODL to meet the increasing demand for higher education.

Originally established in 1958, Anadolu University, a state university, did not start delivering learning content through ODL until 1982 when it started delivering education as a dual mode university to both on- and off-campus students. The main objective of Anadolu University's ODL practices was to provide equality in education. In this regard, openness as a philosophy was at the core of Anadolu University ODL practices, with Anadolu University defining its vision as “to be a global university with a focus on lifelong learning” (Anadolu University, 2018a, para, 2) and its mission as

to contribute to the accumulation of universal knowledge and culture through education, research, and projects in the fields of science, technology, art, and sports in order to provide high-quality distance and on-campus learning opportunities to individuals at any age, and to produce creative and innovative solutions in line with community needs, with a view to improving the life quality of people in the city, region, country, and world. (Anadolu University, 2018a, para. 2)

These guiding principles were built from the following values: Transparency, accountability, fairness, human-centeredness, innovativeness, creativity, reliability, excellence, and universality (Anadolu University, 2018b).

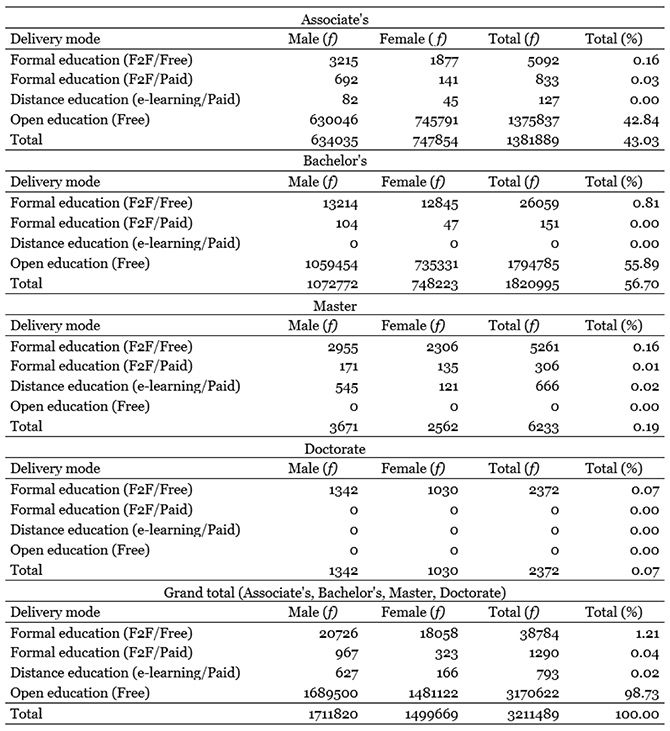

Located in Eskişehir, a city well-known for its science, culture, and youth, the two campuses of Anadolu University feature 17 faculties (bachelor's), three of which are offered as ODL, three applied academic schools, one of which is music and drama, four vocational schools (associate's), nine graduate schools (five of which are at the master's and doctoral level), and 30 research centers. A total of 2,539 academic staff and 1,692 administrative staff are employed by Anadolu University. As a dual-mode university, the student body is 3,211,489 strong, with 39,577 on-campus students and 3,170,622 off-campus students (793 in distance education programs and 3,170,622 in ODL programs). Of the 3,170,622 off-campus students, 1,193,802 active students renewed their enrollment, while 1,976,820 passive students did not renew their enrollment yet reserved their right to do so. Since 1982, the total number of students to have graduated from Anadolu University ODL system is around 2.8 million.

Offering 39 associate's and 19 bachelor's degree programs, Anadolu University ODL programs offer a considerably high number and diversity of programs. Though most of the programs are in Turkish, programs in English and Arabic are also available, and furthermore, Anadolu University teaches Turkish online for free to anyone interested in learning it. Learners across the globe who are enrolled in these programs can take their exams in 18 countries located in three continents. Starting in the 2000s, as a result of the European Union Erasmus Student Exchange Program for on-campus programs and the increasing number of offices, contact points, and exam centers abroad, the student profile grew to be more international.

In parallel with the demand for higher education in Turkey, the number of students who prefer ODL has increased every year (Figure 2). At the advent of ODL in Turkey in 1982, there was a total of 26,796 enrolled students, which grew to 3,170,622 by 2018 (1,193,802 active students and 1,976,820 passive students). While ODL met 13% of the demand for higher education in 1982, in 2018, it met 47% of the overall demand.

Figure 2. Active and passive student numbers (1982-2016).

In terms of gender distribution (Figure 3), while there were 5,945 female students (23%) and 20,851 male students (77%) in 1982 (Büyük et al., 2018), in 2018, there were 1,689,500 male (53%) and 1,481,122 (47%) female students (CoHE, 2018). Considering the change in the number of students by gender from 1982 to 2018, it is clear that ODL in Turkey has been effective in reducing the level of inequity stemming from gender differences and has “helped more women participate in higher education programs across the country over the years, leading to a relatively more normalized distribution of gender in education across the geographical regions” (Gunay Aktas et al., 2019, p. 168).

Figure 3. The number of active male and female student numbers (1982-2016).

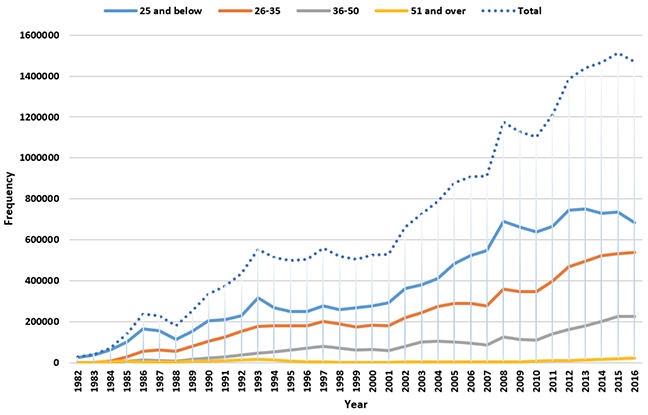

The changes and diversification in the distribution of age over time is particularly interesting (Figure 4). While in 1982, the 25 and below age group constituted the majority of students, in 2016, the 25 and below age group constituted 47%, the 27-35 age group constituted 37%, the 36-50 age group constituted 15%, and finally, the 51 and over age group constituted 1% (Büyük et al., 2018). The pattern in age distribution differs considerably from that of other open universities around the world (Garrett, 2016) in being very similar to conventional on-campus universities. In this regard, the large number of young students enrolled in ODL courses demonstrates that ODL is considered as a viable option, one in high demand for meeting higher education needs in Turkey, and that the distribution of different age groups (Figure 4) is proof that ODL in Turkey supports lifelong learning for those who demand it at any age. Another important point to consider is that the diversity in age groups can serve as an indicator for the need of heutagogy (Canning, 2010), which assumes that teaching and learning processes are a self-determined and self-directed lifelong endeavor and suggests that instructional design and learning strategies should be developed on the basis of this perspective.

Figure 4. Distribution of age at Anadolu University (1982-2016).

Enrollment types also demonstrate a changing pattern through time (Figure 5). Especially after the 2000s, those who have an associate's degree and wish to enroll in a bachelor's degree program on the basis of their scores on the vertical transfer exam, as well as those who are already qualified and hold an associate's or bachelor's degree, increase steadily, while those who are enrolled based on the central university entrance exam decrease when compared to other types of enrollment. This confirms the view by Tait (2018b) who reported that “some open universities have a significant appeal to students who are already well-qualified but wish to continue learning later in life” (p. 16).

Figure 5. Enrollment types at Anadolu University (1982-2016).

Overall, the data on Anadolu University demonstrate that the figures related to student numbers, cost, and budget are massive, being on a scale which can be expected for an open university. Massiveness and scale-space approaches, however, should not be limited to student numbers alone. According to Levy's (2011) description of such implementations (i.e., Massive Open Online Courses [MOOCs]), massive also covers learners' diversity, backgrounds and experiences, the communication tools, the Web technologies, the amount of distributed knowledge and the complexity of the distribution, the overwhelming width and depth of discourse among the participants, the multi-modal nature of the discourse, and finally, the massive amount of time needed to manage and organize. However, it should also be noted that the comprehensiveness attributed to the term massive stems, metaphorically speaking, from the openness philosophy, which acts like a compass and lighthouse for those who seek knowledge. This indicates that the term open is subject to changes and evolves over time, which points to the need to define it accordingly if the role of open universities is intended to be identified within the ecology of higher education in the 21st century.

For teaching and learning purposes, both online and offline materials are used and provided to every student of Anadolu University, Open Education Faculty. At Anadolu University, a wide array of learning materials are available, and all of these materials are based on course books that are delivered through branch offices and made accessible through the Anadolu E-Campus (Learning management system [LMS]). The core materials include course books, and any other materials are generated in line with the content provided in these books (e.g., printed book, e-book, interactive e-book, audio book, chapter summaries, tests, quizzes, chapter videos, interactive videos, interactive multimedia chapters, game-based quiz applications).

Students can access their learning materials through the LMS of Anadolu University, where all available materials are categorized according to the relevant chapter of course books. Moreover, students can participate in either synchronous or asynchronous Web-based courses. Lastly, in addition to these learning spaces, students can also attend face-to-face courses, offered in all provinces in Turkey, on designated dates.

Outside of the learning materials and spaces offered in accordance with the curriculum, students can join learning communities (book, cinema, photography, history, and music), where they can socially interact with other students. Through AKADEMA, the massive open online course (MOOC) platform of Anadolu University, students can attend various courses from which they can earn certificates. In brief, Anadolu University provides an impressively wide spectrum of on- and offline learning materials, spaces, and opportunities, a feature which is thought to be critical to narrowing the information gap and digital divide.

The Anadolu University ODL system offers proctored exams at designated exam centers, and as an open university that deals with a massive number of students, it mostly employs summative assessment techniques, which are common in many open universities (Karadag, 2014). At Anadolu University, ODL students are generally assessed and evaluated through multiple choice questions, but there are specific programs where assessments and evaluations are conducted with open-ended questions and assignments/projects. Based on bell curve statistics, the grades are defined separately for each course.

Organizing exams is a massive undertaking. For instance, in the 2017 Fall term, over a period of two days and four sessions, 1,371,589 students (including 2,242 imprisoned students and 4,869 disabled, handicap, or students with special needs) attended exams in 202,227 classrooms. The 2,242 imprisoned students were provided all learning materials (especially offline materials that they could use in prisons), and they were able to attend their exams at the site of their respective prisons. More importantly, the 4,869 disabled, handicap, or students with special needs were able to get their learning materials designed according to their needs (audio materials, materials written in braille alphabet, subtitle support, etc.) and upon request, they were able to attend their exams at their homes, hospitals, or any other facility they resided. The total number of people who were in charge of facilitating exams in the 2017 Fall term was 502,002 in Turkey and across the globe. The total number of ODL students who attended exams in different sessions over a period of two days was 3.6 million.

Academic and non-academic support services are provided through 113 branch offices in Turkey and 9 branch offices abroad. Both active and passive students can receive academic and non-academic support through these offices. Moreover, a call center, open 24/7, has been available to all Anadolu University ODL students since 2016. ODL students, however, can manage most of their student affairs through the ANASIS system, or through a service system integrated with the e-government platform of Turkey. Apart from these communication opportunities, students also have access to face-to-face and online (both synchronous and asynchronous) support.

Anadolu University further functions as a particularly remarkable institution for its research and development, and knowledge production and dissemination. In addition to the many programs it offers in various fields at the master's and doctoral levels, there are three ODL programs that offer master's (with and without thesis) and doctoral degrees (Kocdar & Karadag, 2015). Research trends in ODL in Turkey demonstrate that Anadolu University is the leading institution in terms of its contribution to ODL, where the specific focus has been on online learning processes (Bozkurt et al., 2015; Durak et al., 2017). In this context, it can be concluded that by investing in research and development, Anadolu University has contributed to the field of ODL by producing knowledge in an open university at scale, and by encouraging change and innovation for Turkish higher education.

A university with more than one hundred thousand students is defined as a mega university (Daniel, 1996). Under this definition, there are three core components: Distance teaching/ODL, higher education, and size. Accordingly, the primary activities of these universities include delivering learning content through ODL at the higher education level, demonstrating economies of scale, having competent logistics, and using information and communication technologies (ICT) to promote open learning (Daniel, 1996). The student numbers increased enormously starting from the new millennium (Daniel, 2011), with the student numbers in some open universities reaching into the millions (Tait, 2018b). Interestingly, whereas mega universities had originally intended to reach adult students, the situation has changed, with young students now dominating the student body of these universities, resulting in the motto of open universities shifting from that of “second chance to get a degree” to “first choice for lifelong learning” (Daniel, 1996, p. 37).

When open universities first emerged, there was skepticism regarding survival, sustainability, and necessity (Keegan & Rumble, 1982). However, most open universities managed to mature and survive by adopting competitive strategies for the global higher education field. Tait (2018b) argues that we now need to figure out the next phase for open universities and the direction we should go in moving forward. Currently it is known that:

The important factors, such as the globalization, the changes in population movements, the transformation into an information society, the increasing competition in economics, and the changes and progresses in information and communication technologies have an ongoing impact on all fields of life, including higher education. The areas that these factors affect in higher education range from the administration of higher education institutions, the institutional structuring and the diversity of services offered to the financing structure, R&D activities and international cooperation. (Özgür & Koçak, 2016, p. 202)

In addition to these above-stated factors, some of the early mega universities have transformed into giga institutions with more than one million students. This, of course, requires developing new strategies in management, educational approaches, support services, funding, and logistics. Moreover, some of these universities have turned into global campuses, now exposed to digital transformation, and their student populations are globally diverse. This requires distinguishing mega universities from giga universities and coming up with an operational definition for the latter. In this context,

a giga university can be defined as a higher education institution that operates locally or globally, that has adopted an open and distance learning approach capable of reaching 1M or more students, and that has developed strategies to create a mass open learning ecology.

Under this definition, Anadolu University, which was originally recognized as a mega university, can now be defined as a giga university. Operating globally, with a massive number of learners and economy of scale, Anadolu University meets half of the demand for higher education in Turkey and has put forth strong local and global efforts to provide access to knowledge and encourage lifelong learning.

This study has explored the current state of open universities by focusing on Anadolu University, which is considered to be a unique case, insofar as it demonstrates a higher education institution that has transformed from a mega to a giga university. The examination of Anadolu University revealed some significant issues to consider. For example, as revealed in the Learning Materials and Spaces section, open universities play a critical role in narrowing the information gap, by providing learning opportunities for anyone who demands it, and in narrowing the digital divide, by diversifying online and offline learning materials and access options. As explained in the Learners' Profile and Demographics section, open universities also can enhance equality of opportunity in education by providing different entry points to higher education and encourage lifelong learning. More importantly, open universities can balance out gender inequalities in education. Finally, as indicated in the Knowledge Production and Dissemination section, by experimenting with innovative approaches, open universities can be a catalyst of change and innovation and serve as a role model for other higher education institutions.

Based on the results of this investigation of open universities and the experiences that have been documented, the following suggestions can be made for future research on this subject. First, considering the tectonic shifts and paradigm changes stemming from developments in ICT, the possibilities provided by online, networked, and distributed learning spaces, and the increasing demand for higher education, there is a need to redefine the idea of openness in the 21st century and to identify its core concepts in order to create a common mission and vision among all open universities. Second, as in the case of Anadolu University, open universities operate globally, and therefore it can be suggested that open universities engage in international collaborations and partnerships to exchange experiences and know-how. Third, since learner profiles have become more international and diverse, it is important to conduct more research about culturally relevant open pedagogies. Fourth, as open universities welcome learners from diverse backgrounds, who are independent in time and space and self-directed, curricula should be developed and designed based on the principles of heutagogy to provide self-determined learning experiences. Lastly, considering that the student numbers in mega and giga open universities are massive, and that every decision affects millions of students, the unbundling of services should be viewed as a viable option to provide effective, efficient, and attractive learning experiences for those who enter the world of open learning.

The research is supported by Anadolu University Scientific Research Projects Commission with grant no: 1704E087, 1805E123 and 1905E079.

Anadolu University. (2018a). Anadolu at a glance. Retrieved from https://www.anadolu.edu.tr/en/about-anadolu/institutional/anadolu-at-a-glance

Anadolu University. (2018b). Vision & mission. Retrieved from https://www.anadolu.edu.tr/en/about-anadolu/institutional/vision-and-mission

Askar, P. (2005). Distance education in Turkey. In C. Howard, J. Boettcher, L. Justice, K. Schenk, P. Rogers, & G. Berg (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distance learning (pp. 635-640). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Baker, F. W. (2017). An alternative approach: Openness in education over the last 100 years. TechTrends, 61(2), 130-140. doi: 10.1007/s11528-016-0095-7

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology, 1(3), 311-320. doi: 10.1037//1089-2680.1.3.311

Berberoğlu, B. (2015). Open and distance education programs of Anadolu University since the establishment. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 3358-3365. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.1004

Bozkurt, A. (2017). Türkiye'de uzaktan eğitimin dünü, bugünü ve yarını [The past, present and future of the distance education in Turkey]. Açık Öğretim Uygulamaları ve Araştırmaları Dergisi (AUAd), 3(2), 85-124. Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/auad/issue/34117/378446

Bozkurt, A. (2019). From distance education to open and distance learning: A holistic evaluation of history, definitions, and theories. In S. Sisman-Ugur, & G. Kurubacak (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning in the age of transhumanism (pp. 252-273). Hershey, PA: IGI Global. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-8431-5.ch016

Bozkurt, A., Genc-Kumtepe, E., Kumtepe, A. T., Erdem-Aydin, I., Bozkaya, M., & Aydin, C. H. (2015). Research trends in Turkish distance education: A content analysis of dissertations, 1986-2014. The European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning (EURODL), 18(2), 1-22. 10.1515/eurodl-2015-0010

Bozkurt, A., Koseoglu, S., & Singh, L. (2019). An analysis of peer-reviewed publications on openness in education in half a century: Trends and patterns in the open hemisphere. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 78-97. doi: 10.14742/ajet.4252

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe, Ill: Free Press.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27-40. doi: 10.3316/qrj0902027

Boydston, J. A. (Ed.). (2008). The collected works of John Dewey, Index: 1882-1953. SIU Press.

Büyük, K., Kumtepe, A. T., Uça Güneş, E. P., Koçdar, S., Karadeniz, A., Özkeskin, E. … Öztürk A. (2018). Uzaktan öğrenenler ve öğrenme malzemesi tercihleri [Distance learners and their learning material preferences]. Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi. Retrieved from https://ekitap.anadolu.edu.tr/#bookdetail172074

Büyükerşen, Y. (2009). Zamanı durduran saat [The watch that stops the time]. İstanbul: Doğan Egmont Yayıncılık.

Canning, N. (2010). Playing with heutagogy: Exploring strategies to empower mature learners in higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 34(1), 59-71. doi: 10.1080/03098770903477102

Cekerol, K. (2012). The demand for higher education in Turkey and open education. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 11(3). Retrieved from http://www.tojet.net/articles/v11i3/11332.pdf

CoHE. (2018). Higher education statistics. Retrieved from https://istatistik.yok.gov.tr/

Cronin, P., Ryan, F., & Coughlan, M. (2008). Undertaking a literature review: A step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing, 17(1), 38-43. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.1.28059

Daniel, J. (2011). Open Universities: What are the dimensions of openness?. Commonwealth of Learning. Retrieved from http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/1292

Daniel, J. (1996). Mega-universities and knowledge media: Technology strategies for higher education. London: Psychology Press.

Demiray, U. (2012). The Leadership Role for Turkey in Regional Distance Education. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 10(2), 14-35. Retrieved from http://www.asianjde.org/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/196/179

Dewey, J., Boydston, J. A., & Ross, R. G. (1983). The middle works of John Dewey: 1899-1924 (Vol. 13). Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press.

Durak, G., Çankaya, S., Yunkul, E., Urfa, M., Toprakliklioğlu, K., Arda, Y., & İnam, N. (2017). Trends in distance education: A content analysis of master's thesis. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 16(1), 203-218. Retrieved from http://www.tojet.net/articles/v16i1/16118.pdf

Garrett, R. (2016). The state of open universities in the Commonwealth: A perspective on performance, competition and innovation. Commonwealth of Learning. Retrieved from http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/2048

Geray, C. (2007). Distance education in Turkey. International Journal of Educational Policies, 1(1), 33-62. Retrieved from http://ijep.icpres.org/vol1_1/Geray(1)1_33_62.pdf

Gunay Aktas, S., Genc Kumtepe, E., Mert Kantar, Y., Ulukan, I. C., Aydin, S., Aksoy, T., & Er, F. (2019). Improving gender equality in higher education in Turkey. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 12(1), 167-189. doi: 10.1007/s12061-017-9235-5

Gursoy, H. (2005). A critical look at distance education in Turkey. In A. A. Carr-Chellman (Ed.), Global perspectives on e-learning: Rhetoric and reality (pp. 115-126). London: Sage Publications.

Harris, D. (1987). Openness and closure in distance education. Basingstoke: Falmer Press.

Hug, T. (2017). Openness in education: Claims, concepts, and perspectives for higher education. Seminar.Net, 13(2). Retrieved from https://journals.hioa.no/index.php/seminar/article/view/2308

Karadag, N. (2014). Açık ve uzaktan eğitimde ölçme ve değerlendirme: Mega üniversitelerdeki uygulamalar [Assessment and evaluation in open and distance learning: Practices in mega universities] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Anadolu University, Eskişehir. Retrieved from https://ekitap.anadolu.edu.tr/#bookdetail171957

Keegan, D., & Rumble, G. (1982). The DTUs: An appraisal. In G. Rumble & K. Harry (Eds.). The distance teaching universities. London: Croom Helm.

Kilinç, B. K., Yazici, B., Gunsoy, B., & Gunsoy, G. (2016). A qualitative statistical analysis of the performance of open and distance learning: A case study in Turkey. Journal of Scientific Research and Development, 3(7), 86‐90. Retrieved from http://jsrad.org/wp-content/2016/Issue%207,%202016/13jj.pdf

Kocdar, S., & Karadag, N. (2015). Identifying and examining degree-granting programs for distance education experts: A preliminary analysis. In G. Kurubacak, & T. Yuzer (Eds.), Identification, evaluation, and perceptions of distance education experts (pp. 190-210). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Latchem, C., Abdullah, S., & Xingfu, D. (1999). Open and dual‐mode universities in East and South Asia. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 12(2), 96-121. doi: 10.1111/j.1937-8327.1999.tb00132.x

Latchem, C., Özkul, A. E., Aydin, C. H., & Mutlu, M. E. (2006). The open education system, Anadolu University, Turkey: e‐transformation in a mega‐university. Open Learning, 21(3), 221-235. doi: 10.1080/02680510600953203

Levy, D. (2011). Lessons learned from participating in a connectivist massive online open course (MOOC). In Y. Eshet-Alkalai, A. Caspi, S. Eden, & Y. Yair (Eds.), Proceedings of the Chais conference on instructional technologies research 2011: Learning in the technological era (pp. 31-36). Raanana, Israel: The Open Univeristy of Israel. Retrieved from http://chais.openu.ac.il/research_center/chais2011/download/f-levyd-94_eng.pdf

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (2012). Distance Education: A Systems View of Online Learning (3rd Ed.). Wadsworth, USA: Cengage Learning.

Özgür, A. Z., & Koçak, N. G. (2016). Global tendencies in open and distance learning. Journal of Education and Human Development, 5(4), 202-210. doi: 10.15640/jehd.v5n3a19

Ozkul, A. E. (2001). Anadolu University distance education system from emergence to 21st century. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 2(1), 15-31. Retrieved from http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/makale_goster.php?id=19

Peter, S., & Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7-14. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.23

Peters, M. (2008). The history and emergent paradigm of open education. In Peters, M. A., & Britez, R. G. (Eds.), Open education and education for openness (pp. 3-15). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Pomerantz, J., & Peek, R. (2016). Fifty shades of open. First Monday, 21(5). Retrieved from http://www.ojphi.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/6360/5460

Rumble, G. (2007). Social justice, economics and distance education. Open Learning, 22(2), 167-176. doi: 10.1080/02680510701306715

Selvi, K. (2006). Right of education and distance learning. Euroasian Journal of Educational Research, 2006(22), 201-211. Retrieved from http://ejer.com.tr/en/archives/2006-winter-issue-22

Shale, D. (1997). Innovation in international higher education: The open universities. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 2(1), 7-24. Retrieved from http://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/310/204

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek, S. (2011). Teaching and learning at a distance (5th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Smith, M. L., & Seward, R. (2017). Openness as social praxis. First Monday, 22(4). doi: 10.5210/fm.v22i4.7073

Smith, P. J. (2005). Distance education: Past contributions and possible futures. Distance Education, 26(2), 159. doi: 10.1080/01587910500168819

Tait, A. (2008). What are open universities for?. Open Learning, 23(2), 85-93. doi: 10.1080/02680510802051871

Tait, A. (2013). Distance and e-learning, social justice, and development: The relevance of capability approaches to the mission of open universities. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(4), 1-18. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i4.1526

Tait, A. (2018a). Education for development: From distance to open education. Journal of Learning for Development - JL4D, 5(2), 101-115. Retrieved from https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/294

Tait, A. (2018b). Open universities: The next phase. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 13(1), 13-23. doi: 10.1108/aaouj-12-2017-0040

Taylor, R. (1990). South Africa's open universities: Challenging apartheid? Higher Education Review, 22(3), 5-17. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ416845

Turkish National Ministry of Education. (2018). Statistics for Turkish national ministry of education. Retrieved from https://sgb.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_dosyalar/2017_09/08151328_meb_istatistikleri_orgun_egitim_2016_2017.pdf

Turkish Statistical Institute. (2018). Basic statistics: Population and demography. Retrieved from http://www.tuik.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist

Turkish Student Assessment, Selection and Placement Center. (2018a). 2017 higher education exam statistics. Retrieved from http://www.osym.gov.tr/TR,13046/2017.html

Turkish Student Assessment, Selection and Placement Center. (2018b). Hakkında [About]. Retrieved from http://www.osym.gov.tr/

Van den Branden, J., & Lambert, J. (1999). Cultural issues related to transnational open and distance learning in universities: A European problem? British Journal of Educational Technology, 30(3), 251-260. doi: 10.1111/1467-8535.00114

Verduin, J. R., Jr., & Clark, T. A. (1991). Distance education: The foundations of effective practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

The Historical Development and Adaptation of Open Universities in Turkish Context: Case of Anadolu University as a Giga University by Aras Bozkurt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.