Mimi Miyoung Lee

University of Houston

USA

Meng-Fen Grace Lin

University of Houston

USA

Curtis J. Bonk

Indiana University at Bloomington

USA

An all-volunteer organization called the Opensource Opencourseware Prototype System (OOPS), headquartered in Taiwan, was initially designed to translate open source materials from MIT OpenCourseWare (OCW) site into Chinese. Given the recent plethora of open educational resources (OER), such as the OCW, the growing use of such resources by the world community, and the emergence of online global education communities to localize resources such as the OOPS, a key goal of this research was to understand how the OOPS members negotiate meanings and form a collective identity in this cross-continent online community. To help with our explorations and analyses within the OOPS translation community, several core principles from Etienne Wenger’s concept of Communities of Practice (COP) guided our analyses, including mutual engagement, joint enterprise, shared repertoire, reification, and overall identity of the community. In this paper, we detail how each of these key components was uniquely manifested within the OOPS. Three issues appeared central to the emergence, success, and challenges of the community such as OOPS: 1) strong, stable, and fairly democratic leadership; 2) participation incentives; and 3) online storytelling or opportunities to share one’s translation successes, struggles, and advice within an asynchronous discussion forum. While an extremely high level of enthusiasm among the OOPS members underpinned the success of the OOPS, discussion continues on issues related to quality control, purpose and scope, and forms of legitimate participation. This study, therefore, provides an initial window into the emergence and functioning of an online global education COP in the OER movement. Future research directions related to online global educational communities are discussed.

Keywords: Open educational resources (OER), OpenCourseWare (OCW); communities of practice (CoP); global education; Opensource Opencourseware Prototype System (OOPS); opensource; volunteer translators; reification; mutual engagement; joint enterprise; shared repertoire; MIT; global translation; asynchronous discussion threads; Chinese; China; Taiwan

During the past decade, online collaborative technologies combined with a shift in educational practices toward sharing educational contents, have created global educational opportunities never witnessed before in the history of human civilization. These opportunities have supported a change in dispositions to share among renowned institutions and established educational scholars. This shift has already resulted in innovative learning possibilities for every connected citizen on this planet. As individuals and funding agencies recognize some of these opportunities and events, even more far reaching global exchanges and learning outcomes can be developed, tested, combined, and promoted. In partial response to these trends, we examine an Open Educational Resources (OER) community, with the goal of understanding how members negotiate meanings and form a collective identity in this cross-continent online community.

This study focuses on an all-volunteer organization called Opensource Opencourseware Prototype System (OOPS). The OOPS community was a brainchild of Lucifer Chu, whose passion and vision for providing Chinese/ Taiwanese version of opencourseware made OOPS possible (Phipps, 2005). Lucifer, known simply as ‘Luc,’ represents the strong leadership felt by members of the OOPS in that most of the community’s major events are initiated with his ideas. As the Chinese translator of The Lord of the Rings and the founder of Fantasy Foundation, Luc has been a well known entrepreneur and promoter since 2002; his stated purpose is “to promote fantasy arts in the Great China area, cultivate our own Tolkien and J.K. Rowling, and encourage the sharing of knowledge and creative thinking” (Lin, 2006, p. 24). For example, the Fantasy Foundation has been promoting activities such as annual fantasy art competitions and summer fantasy art camps. In addition, it has been hosting several online forums where fantasy arts fans and creators can interact and exchange ideas. Luc’s life story shaped his motivation and inspiration for creating OOPS. His diverse experience also provided him with the ability to start and spread the OOPS project.

In OOPS, we were interested in understanding how the members negotiate meaning and establish their sense of identity through various members of this organization. Using the participant dialogues from the OOPS’s electronic bulletin board followed by participant interviews, we explored many characteristics of this unique community through the theoretical framework of Communities of Practice proposed nearly a decade ago by Wenger (1998). Our analysis of the OOPS data presents an example of a unique application of Wenger’s framework to a growing and vital segment of the global education field. As such, we detail specific aspects of Wenger’s model that apply to the OOPS setting. The OOPS project was initially designed to translate open source materials from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) OpenCourseWare (OCW) site into Chinese and Taiwanese. The most unique aspect of the OOPS is that it originated as a group comprised solely of volunteers of Chinese and Taiwanese speakers from various regions of the world. In the conception of the project, the participants’ collective identity as a ‘grassroots movement’ and the technology enabling the formation of an online network amongst diverse groups of ‘Chinese’ speakers played a key role in its success. The emergence of a community of practice (COP) composed of volunteer members for the purpose of global education is highly unique, but will likely become increasingly common as access to the Internet, and the plethora of open educational resources within it, increases around the globe. This particular study, therefore, is significant in providing an initial window into how such a global education COP forms and later thrives.

The negotiation of meaning in this community takes place on two levels: 1) the act of translation of the MIT contents, and 2) the act of ‘interpretation’ of their practice of translation. Much of this negotiation is centered on understanding the process of translation as well as sustaining the OOPS as an effective volunteer organization. Focusing on the formation of and the activities within the OOPS community, this paper presents a story of the efforts and work behind this unique community and how the participants make sense of their work as a part of a larger open courseware initiative. As indicated, we utilize Wenger’s (1998) ideas related to communities of practice to frame our analysis and discussion.

The paper is organized in the following way: first, a selective overview of the theoretical discussion around communities of practice is introduced. Second, data from the study is presented where the analysis shows the key components of community of practice as manifested uniquely within OOPS. Third, the interpretations on these findings are presented along with future implications for both the OOPS and other similar communities.

Recent learning theories emphasize the importance of collaboration, interaction, and discussion in learning. In social theories of learning, which ideas related to communities of practice are based on, learning is best understood from analyzing participation in social enterprises (Thomas, 2005). These social enterprises need not be physical ones, however. In fact, with the emergence of online communities, scholars have increasingly focused their attention on the variables impacting the effectiveness of virtual communities (Bonk, Wisher, & Nigrelli, 2004; Castells, 2001; Jones, 1997; Rheingold, 2000; Smith & Kollock, 1999). Wenger’s (1998) Communities of Practice framework has been employed to better inform studies of such electronic communities. Communities of practice are groups of people who share a passion or concern for something they do. They learn by engaging in the practice and improving it through interactions with others in the community (Wenger, 1998).

A significant amount of studies have been conducted on various aspects of communities of practice. For instance, some scholars in the COP field have provided overviews of the research (Johnson, 2001) and delineated key principles or components of a COP (Bonk, Wisher & Nigrelli, 2004). In a recent book chapter, Bonk and colleagues (2004) listed ten key principles of a community of practice (e.g., sharing goals, trust and respect, shared history, identity, shared spaces for idea negotiation, influence, autonomy, team collaboration, personal fulfillment, and events embedded in real world practices, and rewards, acknowledgements, and fulfilling personal needs) and the associated online technologies and activities that can support their development. For example, a sense of shared goals, purpose, and mission can be facilitated through activities to create team or community logos and mottos, or vision statements as well as technologies such as help systems, online calendars, site announcements, and streaming videos from community leaders discussing the mission of the community. The development of community identity, sustaining diverse membership, and the growth of expertise in the community, might be fostered through celebration of individual and team accomplishments in that community as well as global chats among the members and other special events. To help develop such identity, there might be synchronous group meetings as well as a designated website or portal for the community to which members could contribute as well as get needed information and knowledge from.

As indicated earlier, since Wenger’s landmark book, there has been much research in the field of virtual online communities. Other COP-related research has addressed issues and typologies of virtual communities of practice (Baek & Barab, 2005; Barab, Kling & Gray, 2004; Dubé, Bourhis & Jacob, 2006; 2005), motivations for participation (Wasko & Faraj, 2000), aspects of voluntary communities of practice (Donaldson, Lank & Maher, 2005), components of global knowledge sharing (Pan & Leidner, 2003; Donaldson, Lank & Maher, 2005), and COP success factors (McDermott, 2001). Still other COP scholars have begun to offer a critical discussion related to designing online communities of practice (Schwen & Hara, 2003).

Schwen and Hara (2003) mention that COPs foster the articulation of “everyday problems of dilemmas of practice” (p. 167). Hara and Kling’s (2002) study of two public defender offices revealed that communities of practice display a sense of shared vision, a supportive culture when problems or issues arise, a great deal of worker autonomy, professional identity, a common practice or set of work procedures, and opportunities to share meaning and collectively build knowledge. Importantly, as will become clear later in this paper, many of these same principles, activities, and technologies are evident in the OOPS community. As everyday practices are often used to exhibit the formation of communities, we will focus on the three dimensions of practice: 1) mutual engagement, 2) a joint enterprise, and 3) a shared repertoire as they are manifested in the community of OOPS (Wenger, 1998). In the following section, we provide an overview of the Opencourseware movement and a brief history of the OOPS project.

Initiated by MIT and its faculty in their effort to provide free and open educational materials to learners around the world, the Opencourseware (OCW) movement represents the new movement to help advance education at the global level. In the case of MIT, the OCW provides visitors with course syllabi, lecture notes, and course calendars for over 1,000 courses. Most of these courses include supplemental materials such as multimedia simulations, problem sets and their solutions, past exams, reading lists, sample student projects, and a selection of video lectures. With its first announcement in April 2001, the MIT OCW pilot site opened to the public in September 2002 and offered 32 courses initially. The site was officially launched in September 2003 with 500 courses online. In 2004, the site received almost 120 million hits from visitors in more than 210 countries, territories, and city-states around the globe.

Many other OCW initiatives have been inspired by the success of the MIT OCW initiative. Utah State University (n.d.) launched its OCW in March 2005, followed by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in April 2005. These two institutions added additional course materials to MIT’s offerings, making the current OCW collection unique around the world. Internationally, six of Japan’s top schools also announced their OCW in May, 2005, expanded to ten in June 2007. Other international institutions such as Paris Technology, Universia (i.e., a consortium of universities in Spain and Portugal) have begun their involvements as well (Atkins, Brown & Hammond, 2007). The growth of the OCW movement has been so fast and far reaching, that the ‘OpenCourseWare Consortium’ was established in summer of 2006 to keep track of all of OCW developments underway and facilitate the communication and international development of OCW. Its mission statement (OCW, n.d.) reads, “The mission of the OpenCourseWare Consortium is to advance education and empower people worldwide through opencourseware” (¶ 2). The OCW Consortium’s website tracks the rapid growth of its members, emerging issues, hot discussion topics, and the latest OCW related news. According to an MIT report in June 2006, over 350 of the online MIT courses had been translated and at least 70 mirror sites existed globally. In addition, the MIT course materials had already been translated into at least 10 different languages, including Chinese, Spanish, and Portuguese.

OOPS is an independent grass roots project, headquartered in Taiwan, designed to translate and adopt Opencourseware OCW for the Great China Region, referring commonly as China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. The most distinguishing characteristic of OOPS is that the project is mainly run by volunteers in various disciplines, recruited from all over the world (see Figure 1). These volunteers choose (‘adopt’) courses and translate them.

Figure 1. The Opensource Opencourseware Prototype System (OOPS) volunteers

In February 2004, the entire MIT OCW site was copied to a local server hosted in Taiwan, signaling the beginning of OOPS (see Figure 2). Through media coverage, bulletin board postings, and forwarded emails, OOPS quickly attracted volunteer translators in cyberspace. After more than three years of operation, OOPS currently includes materials from MIT, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Utah State University, Tufts University, Paris Technology, Japan OCWs, Harvard Extension Schools’ podcasts, Public Library of Science, and a unique collection from Professor Harry Bhadeshia’s (n.d.) education materials from the Phase Transformations and Complex Properties Research Group. In addition to adding more materials for translation, in late 2006, OOPS successfully secured a two-year grant from the Hewlett Foundation, one of the major funding agencies in the OER movement. This funding clearly acknowledged OOPS’ contribution to and growing influence in the global education community. In June 2007, OOPS hosted its first international conference on OCW and e-learning in Taiwan. In this conference, OOPS not only invited OER pioneers to share their first-hand experience with the Taiwanese educational community, it also functioned as a showcase for the three-years of progress and contributions related to OOPS.

Figure 2. MIT OCW mirror site in Chinese

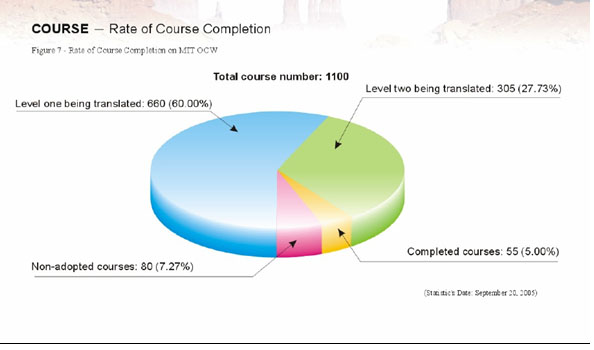

As shown in Figure 3, as of September 2005, of the 1,100 MIT OCW courses, 660 had been adopted for translation at Level One (text), 305 were adopted for Level Two translation (text, video, and audio), 55 courses were completed, and 80 had yet to be adopted. By January 1, 2007 the translation of nearly half of the 1,100 courses had been completed by a network of over 2,200 volunteer translators from more than 22 countries (Lucifer Chu, personal communication, July 18, 2007).

Figure 3. OOPS course adoption and completion of MIT OCW courses

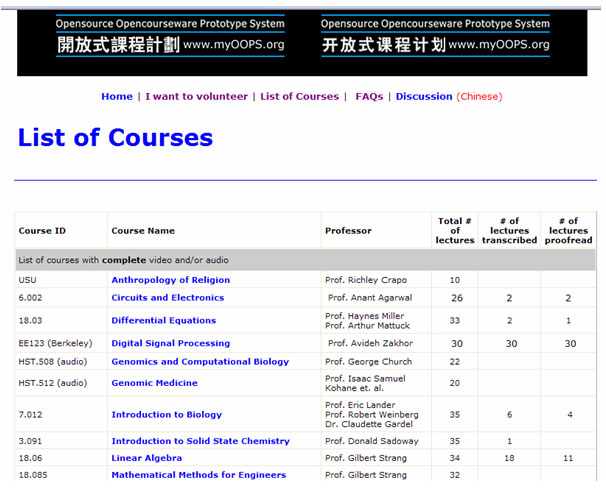

For this paper, three data sources were used: 1) the OOPS online discussion forum, 2) the project website (see Figure 4), and 3) interviews with five participants. This data was originally collected by the second author, and the analysis was later conducted by all the authors using content analysis and story-thread analysis (Lin, 2005) as well as coding methods used in reconstructive analysis (Carspecken, 1996). Content analysis was conducted for online conversations posted between February 2004 and January 2005. A total of 734 threads, or 2,977 responses, were categorized into emerging story lines. These story lines formed the basic understanding of the ecology of this community, which was used as the starting point for participant interviews.

Figure 4. List of MIT courses adopted by OOPS volunteers and progress updates

Participant interviews were primarily conducted between April 2005 and December 2005, with some follow-ups via emails or online chats. Participants were invited based on: 1) the second author’s first-hand involvement and observation with the community, 2) the second author’s contacts with some of the participants during the volunteer activities, and 3) the understanding gained in the above mentioned content analyses. The number of interviews and the duration of each interviews varied, depending mainly on the availability and enthusiasm of each participant. Some participants were interviewed via Skype (a free online phone service). Such online conversations typically lasted over two hours. Other participants communicated mainly via emails during the research period. A series of interviews with two of the participants were conducted mainly through online chats, some of which lasted a few minutes and some lasted more than an hour.

Trustworthiness was established mainly through the following measures: 1) data triangulation that included data sources such as interviews, online postings, and newsletters from project website, 2) peer debriefing that included discussions of interpretations and conclusions between two authors and with other researchers, and 3) member checking that included sharing documents with the participants. As noted, Wenger’s ideas regarding communities of practices guided our analyses. In the following sections, we explore the issues related to mutual engagement, reification, joint enterprise, shared repertoire, legitimate participation, collective identity and harmony, sustaining membership, and leadership in the OOPS community. As will become increasingly evident, each of these respective principles is a vital component of the productivity and livelihood of the OOPS community.

We learn by participating in the specific, local practices, which in turn are negotiated within broader discourses. In this sense, “the act of knowing involves an interaction between the local and the global” (Wenger, 1998, p.141). The globalization of open educational resources originally shared in one language (e.g., English), such as the MIT Opencourseware initiative, epitomizes such local-global interactions. As a prime example, the OOPS community and their project of translation are engaged in the act of making that link between the Chinese speaking population and the available opencoursewares – i.e., bringing globalized content to local populations. The meaning of the practice of translation and localization of the global contents is discussed, questioned, and further negotiated through the narratives of these volunteer participants.

As a volunteer group, the OOPS community shows an extremely high level of enthusiasm and engagement which can be explained by the organization’s grassroots history. The mission statement declared on the homepage indicated:

We wanted to use the spirit of an open source to challenge the groundbreaking idea of knowledge sharing. Our goal is to let more people enjoy the shared knowledge (OOPS Homepage, 2007).

On the discussion forum and through interviews, a sense of idealism among the volunteers was apparent. The OOPS members view their work as an extremely innovative project and take great pride in their participation in ‘opening doors’ to new information for the enormous non-English speaking Chinese population, contributing to more fair distribution of knowledge and power. For example, the following two excerpts were quoted from OOPS’ online discussion forum when volunteers were asked to share their view about OOPS.

As someone once said, “Knowledge is power.” . . . I believe that this “power” should be made available fairly and equally to all. It should go to those with the will and the ability to make the best use of it, not just tothose born [the] to right parents. When it is hoarded by a few, social inequality and disharmony result. In addition, knowledge is one of the few commodities that increase the further [if] it is shared. (Ms. J.)

In addition, providing the educational materials whose contents were created by a university of international renown seemed to give a sense of empowerment to these volunteers. Given that Chinese culture holds top tier universities in the United States in especially high regard, there is additional motivation to lend one’s talents to such a project. As noted in the quote below, such sentiments are apparent in Mr. A’s views about the key role or function of the OOPS.

Make the ‘treasure bank’ for worldwide Chinese; do our best to equalize access to knowledge; use our skills to promote global prosperity; use technology to create a new knowledge-based society. (Mr. A.)

Quoting the line from Spiderman, “with great powers comes greater responsibility,” Lucifer Chu, the founder of OOPS, shared his view about OOPS and called on the volunteers to assume greater social responsibility. Luc’s view about the power of knowledge was revealed and supported by the enthusiastic volunteers.

Volunteers’ apparent subscription to the goal of OOPS was vocally expressed via the online forum used in OOPS. As Wenger (1998) emphasized, different forms of reification at the organizational level help sustain the energy and help build the collective sense of identity as a group – in effect, the tools, symbols, stories, terminology, and concepts used in a COP reify the practice of it. It was clear from our observations that the OOPS project had such a process of reification. Reification in OOPS helped support the high level of enthusiasm and sense of devotion among the volunteers who entered it. That is, having an electronic forum served as a channel of reification by providing a common place to share and exchange dialogues. Members utilized the online forum for information exchanges, ask questions, and debate hot issues. This would be a good example of reification process being “reappropriated into a local process in order to become meaningful” (Wenger, 1998, p. 60). In addition to utilizing an online forum, OOPS made extensive effort to promote project ideas through traditional media such as radio, TV, and newspapers. All these activities were frequently reported on the project website, online forum, and monthly newsletter sent to subscribers via email.

Another key aspect of Wenger’s vision for effective creation and sustainability of a COP involves joint enterprise.In a negotiated enterprise, individual situations and responses to such situations will vary among the members; however, member responses to their conditions will be highly interconnected because they are engaged together in the joint enterprise of the practice, bringing a sense of “real and livable” (Wenger, 1998, p.78-79) form to it. In the OOPS project, the practice of translation presented different situations and various individual problems. The responses, however, were closely connected through the community’s process of defining the meaning of translation. Aspects of this joint enterprise within the OOPS community could be seen in the example of negotiating translation quality.

With its pride as a volunteer community OOPS has an open-door policy in accepting any volunteers who are willing to participate. For this reason, there have been consistent concerns regarding quality control since it came into existence. In response to this, OOPS established some rules regarding its review process in July 2004, several months into the birth of the organization. The review process requires that each piece of translation work go through the translator and an editor before publishing it online. In other words, OOPS utilizes a pre-publishing review model, a model quite different from that of Wikipedia where edits are done after the entry is posted online. Even with the implementation of this review process, the issue of translation quality was still the most discussed topic in the online forum, continuously manifesting members’ concerns. Here are examples of opposing views taken from the forum.

Wrong knowledge is worse than no knowledge.

[F]or those Chinese who come here just to learn, it would be extremely difficult to achieve any learning with this translation quality.

[I]f quality is to be top priority, OOPS must slow down the translation production process, including assessing the abilities of the translators and the editors.

At the root of the issue of translation quality lies the question of whose knowledge is prioritized and why. How should it be determined and who should determine it? The increasing negotiation of meaning regarding these issues among the members of the OOPS community was evident in the online forum. The two additional issues concerning the quality management within OOPS had to do with informing the visitors of the stages of translation and accommodating the visitors from different regions with different dialects and/ or terminologies (Lin & Lee, 2006). About the first issue of how quality should be determined and who should determine it, Luc made his position clear:

All web pages are published with both the original English and the Chinese translations. . . All readers are proofreaders. For us, there will never be a finalized version. Everything is forever up for discussion, and modification. (Lin, 2006, p. 14)

The conversation with Mr. A. revealed a different view. When asked if a review by a university professor could guarantee the translation quality, Mr. A. responded in strong affirmative that institutions like the China Academy of Sciences and universities have been regarded as the highest academic standard.

During the interviews, there were some suggestions for establishing standards to help the quality issues in translation. Mr. A., for instance, approached the quality issue through standardizing the terms and concepts and argued for the need for standards “set by the authority.” Ms. D., on the other hand, pointed to the editors about the current problems with the translation quality.

To be frank with you, I’m worried about the quality of our editors. I had an unpleasant experience with one of them who actually made my translation look worse. .; . As a result, I ignored 99% of his revisions not out of arrogance but my principles in keeping the quality of translation. (Ms. D.)

Ms. D. here shares her frustration about an incident where she felt her work was edited to a lower quality. She subsequently asked Luc to remove the aforementioned volunteer editor’s name from the editors list. Whether relying on the outside authority (Mr. A.) or getting better editors (Ms. D.), conversations related to improving quality continued in the OOPS forum. Unfortunately, no one was able to propose a final answer to this ever-evolving issue.

The act of translation is an effort to contextualize the meaning into the local culture. It is crucial for volunteers to first understand the meaning of the words (the first level of localization) and then be able to deliver it to the readers within their realm of language (the second level of localization). As participants in the various stages of the translation process define the joint enterprise, their responses to and interpretations of these processes were always being negotiated. In the case of the OOPS project, this negotiation can be explained on two levels: 1) the negotiation of meaning taking place in the very act of translation (definition of words, phrases, idioms), and 2) the negotiation of processes in defining the repertoire of the enterprise. Both processes are collective by nature and reveal the full complexity of mutual engagement (Wenger, 1998). Situations would arise that call for the community’s negotiated response to the issues ranging from determining word definitions to more macro issues, such as the possibility of quality control within the project. In the next section, we discuss actual examples of ‘negotiated response to the situation’ shown in the OOPS.

The fact that the membership within the OOPS was based purely on a volunteer basis resulted in some interesting findings. Ms. D., for example, recounted a story where she got extremely angry about the comment of an outsider criticizing the community’s lack of quality control. In her defense of the OOPS community, Ms. D. stressed the autonomy of group participation that “nobody force[d]” the volunteers into anything. She went on to emphasize the fact that the volunteers “are not even forced to finish the translation once [they] adopt a course” (Lin, 2006, p. 134). Ironically, the high level of autonomy that defines the sense of a volunteer group, such as OOPS, seemed to act as an impediment to an effective management of quality. Sometimes members of the OOPS community did not seem to take open criticism very well, however constructive it might be. The situation can be seen as an example where “tight bonds can become exclusive and present an insurmountable barrier to entry” (Wenger, McDermott & Snyder, 2002, p.144). Questions about the quality issues were, at times, interpreted by the translators as personal attacks on their efforts. “I think his comment is an insult to our volunteers” (Ms. D.). She sarcastically called this a “let-us-find-fault activity.”

I feel like a group of people going to a basketball game. He would complain how bad the players are playing. If so, why don’t you come down and play the game yourself? (Ms. D)

As shown in the example above, a sense of defensiveness was evident that “if you are not participating, you don’t have any right to criticize” (Italics ours). The sentiment was based on the fact that the OOPS was already doing everything it could with limited resources, and it needed more volunteers who would ‘actually work’ rather than provide ideas to make it better. In this sense, the OOPS participants that were interviewed seem to clearly regard the core participation (i.e., translating MIT courses or facilitating the process of translation) as the only legitimate participation within it. An outsider’s critique and suggestions were considered ‘lip service’ and clearly not as a form of ‘real’ participation. Does an ‘outsider’ have to earn their right to comment only through actually ‘doing’ the translation? Can criticism be considered peripheral yet a form of legitimate participation?

In effect, the OOPS community does not seem to recognize that critiques from outsiders, though peripheral, should be seen as participation influencing the identity and sustainability of the community. Criticism and suggestions should be used to bolster the community and make it more useful for additional audiences or uses. As the quote below makes evident, the second author, in her extensive analysis of the OOPS (Lin, 2005), also pondered this issue,

I wholeheartedly agreed with Ms. D. in the notion that outsiders may not be able to understand, due to the lack of hands-on experience, certain aspects of OOPS. However, can I not just enjoy watching a basketball game without really knowing how to play? This reminded me of Wikipedia. Do people who consider Wikipedia as a reference source need to have the knowledge and skill to question the credibility of it?

As emphasized by Wenger (1998), “communities of practice can connect with the rest of the world by providing peripheral experiences” (p. 117). It is important to offer them “various forms of casual but legitimate access to a practice without subjecting them to the demands of full membership,” which can be interpreted as the community’s ability to have “multiple levels of involvement” (p.117). In this sense, the OOPS community should be able to consider any critique of ‘outsiders’ as a peripheral form of participation. Their criticism, seen this way, is a first step toward promoting the inbound trajectories, increasing “the degree of permeability” (p. 117) and eventually drawing more full participation from the interested public.

This community was fashioned by Luc Chu and has been sustained under his strong and steadfast leadership. In many instances, he single-handedly promoted the mission of OOPS resulting in enthusiastic responses from many volunteers from all over the world. His personal charisma and name value were directly responsible for the formation of the OOPS. As shown in the name and logo voting illustrated below, Luc was always the one to initiate the major events calling for the whole community’s participation. There was a clear recognition of his leadership and an overall support from the community. In June 19, 2004, Luc created a new thread on the OOPS forum titled “Our name” where he announced, for the first time, the name “OOPS” (see Figure 5). In this forum, Luc wrote:

I contemplated for a while and came up with this name . . . this way, it is easier to introduce OOPS to others. We are looking for volunteers who are willing to design a logo for us. We could have a voting later. (Lin, 2006, p. 111)

Figure 5. The OOPS Logo

Over the following weeks, many discussions were exchanged. Some participants questioned the appropriateness of the name OOPS; they believed members should think twice about the possible name before even designing a logo. Other participants focused on what the name OOPS meant and if it truly reflected on the inherent mission. The discussion quickly evolved into the design itself where several artist volunteers shared their conceptualization of a logo. The OOPS logo was selected through a community vote which took place in the course of 10 days and right before the planned meeting among the OOPS volunteers worldwide on August 15, 2004.

The logo-voting event originated from the discussions about group identity (i.e., a key aspect of a COP, mentioned earlier) and simultaneously forced group members to more deeply reflect on just what their identity should be. ‘Who are we?’ the volunteers asked themselves; they could not easily come to an agreement, however. In response to this dilemma, Luc requested that the volunteers submit a logo design and gave a month to do so. Six designs went into voting stage where participants engaged in a friendly campaigning of their favorite design.

The questions and answers between Luc and the other volunteers during this event revealed his hopes and visions of the group’s future. He did this by explaining the parts of the acronym OOPS, as well as clarifying any questions that the members had during this process. For example, the second author remembers a conversation with Luc that started out as his reply to her questions about using the term ‘courseware.’ While the current effort is only focused on the translation of the MIT ‘courses,’ Luc was envisioning the possibility of Chinese/ Taiwanese open courses in the future. The group took what is regarded as ‘advanced’ contents from MIT, but he also had high hopes for cross-cultural exchanges: “I wish in the next stage, MIT can get some from OOPS” (Lin, 2006, p. 105). As the group was focused on establishing its sense of identity, the importance of ‘branding’ was echoed throughout the logo selection process as shown in one participant’s posting below.

[A] non-profit organization also needs a strong branding . . . on the Internet, branding becomes even more vital. When we do not have a physical place, the network becomes [where] the organization locates. . . A charitable organization’s logo should represent the organization’s vision. (Participant posting)

In this sense, the name OOPS not only defined the values and practice of the group currently, it served as a reification of the future direction that could be shared by the whole community. As dissemination of opencourse materials was also a large part of the OOPS’ mission, Luc and others saw the need for a good visual identification system and thought it crucial to work toward the branding of their name and logo.

During these discussions about the group name and the branding issues, an interesting incident occurred that revealed the OOPS’s attitude or disposition toward conflict avoidance. When Luc created a new thread on the discussion forum, titled “Our name” introducing the name OOPS, someone quickly posted a reply by saying, “Logo is a form of visual communication. Maybe we could incorporate the image of Taiwan, to promote Taiwan to the world, of the image of tolerance (technology + humanity + beautiful island).” Immediately following this message was a jolting one-liner from a volunteer from Mainland China; “ Taiwan is not a country.” The posting below by Mr. A. is a good representation of the community’s sentiment regarding this incident.

Everyone, stop. If we keep at this issue, there will be trouble. Let’s not get to that point. We are from two different places, different social environment, different education [system], and different political party. However, what we are doing collaboratively is for the benefits of the larger Chinese community, not for the debates of the two- China. Can we leave this discussion out? Let’s not talk politics…I suggest logo should not carry any political implication. Even though this is a Taiwanese-based project, its goal is for the global Chinese. (Mr. A., italics ours)

The fact that sensitive issues were avoided and purposefully moved out of discussions points to this community’s current emphasis on harmony. When a sensitive topic such as the issue of ‘China/Taiwan’ arose, the community chose to avoid it and strictly adhered to issues of translation. Similarly, in late 2004, there was an incident where discussions about quality became overheated and quickly turned into flaming between Luc and an anonymous visitor. Luc deleted those ‘inappropriate’ postings immediately. When questioned later, he regretted that the incident occurred, but empathized that he could not allow some minor disagreements collapse the entire community, a phenomenon he had witnessed first hand in another online community. Such actions are in line with Smith’s (1999) finding that people whose view of community is that of harmony and homogeneity see conflict as being disruptive to social integration. They usually try to manage the sources of conflict or argument for greater system unity (Deutsch, 1973; Filley, 1975 cited in Smith, 1999). This tendency toward community harmony is due to the commonly mistaken assumption of peaceful coexistence and mutual support at all times in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). What is more important for the evolution and maintenance of the COP, however, is for disagreements and challenges to be considered as legitimate forms of participation (Wenger, 1998). This view of disagreements and challenges is not present in the current state of OOPS. On the contrary, OOPS seems to emphasize the importance of politeness in communication.

As shown above, the OOPS community is alive with principles Wenger laid out a decade ago regarding communities of practice. As an example, volunteer translators are quickly recognized as legitimate participants in the translation process. Mutual engagement is seen in the online discussions and interactions among the many volunteer translators of OOPS. They are highly focused to translate MIT course documents to Chinese, thereby providing educational value for the world, which coincidentally, is free and openly accessible. That is their joint mission or enterprise – to better the world. And why not? Knowledge from MIT is, indeed, very powerful, whether it be from courses in chemistry, physics, history, economics, literature, environmental sciences, engineering, architecture, or some other area. There are millions of people who could benefit for the efforts of OOPS community members.

At the same time, they have support from other OOPS members in the online discussion forums. Such forums and associated stories related to difficulties or successes in course translation help reify the OOPS community. In these stories, they share their ideas, successes, tricks of the trade, problems, and overall experiences with each other. OOPS participants might also discuss the quality of the products that they are producing and begin to establish community standards and norms. And when combined with Luc’s leadership and decision-making, there is a collective identity and sense of peaceful harmony within the OOPS community. It is a welcoming environment where members can vote on logos, names, and other issues of the community. Despite this democratic flavor, tensions, challenges, and controversial issues are avoided in favor of producing courses for the greater good of society.

Three issues seem key to the sustainability and success of this community: 1) the leadership by Luc Chu within OOPS, 2) the incentives for continued participation within OOPS, and 3) the opportunities for storytelling that can provide support or scaffolds for new OOPS volunteers while capturing the knowledge of experienced ones. It is interesting to point out that each of these three areas relate, in some way, to the recognition of the members of the OOPS community – the more senior or experienced individuals as well as the newcomers. It is people that matter and that, in effect, make up any COP. We explore each of these three issues below.

The common thread that binds all these different aspects of the OOPS as a community, is Luc’s leadership whose vision and effort, as mentioned earlier, founded the organization. It was also clear throughout our study that he very much valued the harmony of the OOPS community. One example of such effort is seen by his earlier censoring of potentially controversial topics –i.e., when he removed some postings from the online discussion forum. Such instances of censorship, however, can prevent “occasions for the production of new meanings” (Wenger, 1998, p. 84). Despite the need for some controversy and debate to promote the generation of new meanings, it seems that an online community of volunteers such as OOPS needs a clear and strong leader to cultivate peace and mutual understanding. As with any community, there is perhaps a tension between the stability such leadership offers and the unrestricted or free flow of thoughts and ideas.

Judging from the findings, it looks like the very nature of the OOPS as a volunteer organization at times can work against productivity. Because the participants were mostly volunteers, they focus mainly on participation itself. This explains why they tended to move toward the ‘easier’ tasks (the first level translation of MIT courses – text only) than the ‘harder’ tasks (the second level translation/ editing – text, audio, and video translation). This was a key reason behind the quality ‘problem.’ Some measures have been taken to mitigate this problem, however. Luc recently hired several editors whose work will be compensated monetarily so that more difficult course components can be translated and quality standards can be better modeled and established. These editors will help Luc with some of the difficult decision-making within OOPS. Of course, when the community empowers people to make decisions, add to community resources, celebrate accomplishments, and impact on the shared history of the COP as it unfolds, then productivity and performance can be peaked and members of the COP can start to gel, and foster feelings of shared identity and purpose, and coalesce members respective talents and interests.

As Orr (1990) points out, “details of practice” are “part of the information circulating in the community memory” (p. 170). In the case of the OOPS, the act of storytelling among the members becomes a crucial means toward establishing the collective memory and shared repertoire. The telling and sharing of stories about their own processes of translation is vitally important to the community for many reasons, including: 1) helping to diagnose the state of trouble concerning emerging problems or situations, and 2) acting as repositories of accumulated wisdom (Brown & Duguid, 1991). Narratives are central to the growth and survival of communities since they help in “finding or creating meaning in an inherently ambiguous situation” (Orr, 1990, p. 176). In OOPS, the discussion forum serves as the gateway for members to share the repertoires of their practices and form a sense of collective identity as volunteer translators. In order to capture a vast amount of postings and interactions in the OOPS discussion forum, Lin (2005) used a unique method of analysis called “story thread analysis” where ‘a thread’ of postings is used as a unit of analysis. Such methods can document the emergence of a COP as well as its struggles, challenges, key participants, successes, and pressing issues.

At indicated, the OOPS has been highly successful in recruiting new volunteers. The community, however, needs a better system for sustaining old members as many volunteers come for a short stint and then promptly leave. When they depart, so too leaves a valuable knowledge base for translating documents, emotional supports, and perhaps even some of the historical or organizational memory of this COP. While many OOPS participants used the online discussion forum within it to post questions and share their stories, the community could benefit from a more organized archival system capturing and passing down these valuable stories. In this way, participants can have a shared point of reference where the history of mutual engagement is captured. Along these same lines, what seems currently lacking within the OOPS are ways of documenting OOPS policies, procedures, events, and overall history. Such documentation would enhance the sense of identity and shared history within the OOPS, as well as other key principles of a COP.

There are many directions for additional research in this area. For instance, other studies might attempt to document key principles or features that were lacking in global education or knowledge sharing communities of volunteers that ceased to exist. Other research might compare COP principles in volunteer and non-volunteer communities where the goal is the creation, dissemination, compilation, or translation of globally shared educational resources. Still other investigations in this area might attempt to document the creative spark or initial impetus for such a COP so that the innovative spirit, ideas, and energy as well as the associated positive individual and community changes can perhaps be promoted in other communities, countries, or regions lacking such initiatives or wishing to advance upon what already has been initiated.

Wherever the research in this area heads, projects, such as OOPS, have massive implications for the open and distance learning field. For instance, they provide a means to repurpose existing online learning materials for those previously lacking of such educational resources and opportunities. With the global translation of educational materials from prestigious colleges, universities, institutions, and organizations in North America, Europe, Asia, and elsewhere, online learners who previously were left at the back door of education can now do much more than peek inside; they can interact with advanced learning materials and share such access with their friends and family. With MIT courses already available in Mandarin as well as English, a huge portion of the world’s population can study such materials asynchronously and, perhaps, debate ideas synchronously with their friends, as well as those who they may never physically meet. This is only the tip of the iceberg since translation efforts to still other languages are currently pushing such learning possibilities even further.

Another benefit for the field of open and distance learning is to create a discussion about what resources are most beneficial or important for an online course. As more courses are translated, bottlenecks and inefficiencies in the learning and instructional design process become more apparent. At the same time, global translation will foster greater experimentation with the delivery of online courses and programs. For instance, while there are accreditation, licensing, copyright, and other related issues that need to be addressed, bold and charismatic leaders, such as Lucifer Chu, can create the innovative partnerships necessary for translated courses from MIT and other universities to someday be re-packaged into certificate and other degree programs in Taiwan, mainland China, or other countries. Even without such partnerships, a plethora of novel online and distance learning course experiences are already possible.

Of course, once translated, the online course materials are always there. Within minutes of inspiration, adult learners in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Hsinchu, or Taipei, can decide to access and learn from courses originally created at MIT. Learners can proceed to learn flexibly, as time allows. When this occurs, translated OCW materials could inspire individuals who have work and family responsibilities to pursue educational opportunities that they previously thought impossible. Enhanced learning is only part of the equation; learning from MIT courses (as well as those from other colleges and universities) could also boost learners’ self-esteem and sense of self-worth. At a societal level, the process of translation and the sharing of rich educational materials can foster, and support international relations between east and west and between participating countries or parties. Clearly, mankind benefits as educational opportunities from projects like MIT’s OCW and the OOPS are made available to all.

Finally, there are vast implications for the translators. Their shear involvement in projects, such as the OOPS, increases their awareness of online learning resources and can transform their own educational outlooks, appetites, and fire new ambitions. At the same time, OOPS translators may be downloading, translating, and sharing documents as a way of reifying their own practices. They might also use it as a means of promoting their highly unique community of practice to potential translators and support personnel, thereby expanding their joint enterprise. The ‘meta-awareness’ of the importance of sharing and discussing documents within their own community of practice may nudge OOPS translators from local document editing concerns into a higher level of awareness related to educating other translators. As this process of reification occurs, projects such as the OOPS – under the visionary leadership of people like Lucifer Chu – are laying the foundation for other global online educational opportunities and translation communities. Research on such communities during the next few years should prove exciting and critical for the global online open education movement.

The OOPS is a unique project that has the potential to impact more than one billion people. With the continued expansion and use of Internet technologies and resources for education and training of hundreds of millions of people around the world each day, open educational resources (OER) such as the MIT Opencourseware project and projects like the OOPS which significantly expand upon its original focus, will no doubt play an increasing role in educating the citizenry of this planet. Understanding how such communities are established, cultivated, and sustained perhaps is among the most vital and complex issues that can be addressed today by educators, politicians, and, of course, the learners of this small planet (Wenger, 2004). The coming decade will undoubtedly witness the emergence of innumerable communities of online learners, instructors, translators, instructional designers, and other stakeholders in the OER movement. It is not too surprising that these forms of online communities are not yet fully understood given that such global educational activities were never previously possible; at least not at the speed and intensity that such events are occurring today.

In response to the massive spike in online educational opportunities and global sharing taking place today through many different types and levels of virtual communities, we have attempted to provide a window on one such online community – the OOPS. As some of the earlier quotes and comments indicate, not all aspects of the OOPS community are evolving at a same speed – areas that can be interpreted as a sign of mature community coexist with areas that need to be improved into a mature community. Of course, as alluded earlier, much more needs to be researched and better understood. This is a start. Hopefully, others will become excited by the opportunities and challenges of free and open educational resources, and make their own respective contributions whether it is from a personal course one teaches or a translation of the course materials and resources of someone else. At the same time, those in administrative positions have the power to consider the sharing of entire programs or course catalogs with the world community. In any of these situations, educational progress will have been made and new possibilities will have arisen. As new global education volunteer communities emerge, one can look at the OOPS project for inspiration and modeling of something truly unique and important taking place in education today.

Atkins, D., Brown, J. S., & Hammond, A. (2007). A Review of the Open Educational Resources (OER) Movement: Achievement, challenges and new opportunities. Retrieved July 15, 2007, from http://www.hewlett.org/Programs/Education/OER/OpenContent/Hewlett+OER+Report.htm

Baek, E. O., & Barab, S. (2005). A study of dynamic design dualities in a web-supported community of practice for teachers. Educational Technology & Society, 8(4), 161-177

Barab, S. A., Kling, R., & Gray, J. H. (Eds.). (2004). Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bhadeshia, H. (n.d.). Professor Harry Professor Harry Bhadeshia’s Phase Transformations and Complex Properties Research Group homepage. Retrieved October 24, 2007 from: http://www.msm.cam.ac.uk/phase-trans/Bhadeshia.html

Bonk, C. J., Wisher, R. A., & Nigrelli, M. L. (2004). Learning communities, communities of practice: Principles, technologies, and examples. In K. Littleton, D. Miell & D. Faulkner (Eds.), Learning to collaborate, collaborating to learn (pp. 199-219). Hauppauge, NY.: Nova Science Publishers.

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities of Practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organizational Science, 2(1), 40-57.

Carspecken, P. (1996). Critical Ethnography in Educational Research: A theoretical and practical guide. New York: Routledge.

Castells, M. (2001). Internet Galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, business and society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chu, Lucifer. Personal communication, July 18, 2007.

Donaldson, A., Lank, E., & Maher, J. (2005). Connecting through communities: How a voluntary organization is influencing healthcare policy and practice. Journal of Change Management, 5(1), 71-86.

Dubé, L., Bourhis, A., & Jacob, R. (2006). Towards a Typology of Virtual Communities of Practice, Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management, 1, 69-93.

Dubé, L., Bourhis, A., & Jacob, R. (2005). The impact of structural characteristics on the launching of intentionally formed virtual communities of practice. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 18(2), 145-166.

Hara, N., & Kling, R. (2002). Communities of practice with and without information technology. Paper presented at the American Society of Information Science and Technology, Philadelphia, PA.

Japan Open Courseware Consortium (n.d.). Japan’s Open Courseware Consortium OCW homepage. Retrieved October 21, 2007 from: http://www.jocw.jp/

John Hopkins University (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s OCW. Retrieved October 21, 2007 from: http://ocw.jhsph.edu

Johnson. C. (2001). A survey of current research on online communities of practice. Internet and Higher Education, 4(1), 45-60.

Jones, S. (1997). Virtual culture: Identity and communication in cybersociety. Thousand Oaks , CA.: Sage.

Lin, M. F. (2005). Story Thread Analysis: Storied lives in an online community of practice. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning, 2(9), 61-82.

Lin, M. F. (2006). Building Communities and Sharing Knowledge: A narrative of the formation, development and sustainability of OOPS. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Houston, Houston.

Lin, M. F, & Lee, M. (2006). E-learning Localized: The case of the OOPS project. In A. Edmundson (Ed.), Globalization in Education: Improving education quality through cross-cultural dialogue (pp. 168-186). Hershey, PA.: Idea Group.

McDermott, R. (2001). How to design live community events. Knowledge Management Review, 4(4), 103-117.

OCW Consortium (n.d.). Open CourseWare Consortium homepage. Retrieved October 21, 2007 from: http://www.ocwconsortium.org/

OOPS (2007). OOPS (Opensource Opencourseware Prototype System) homepage. Retrieved November 9, 2007 from http://www.myoops.org/twocw/

Orr, J. (1990). Sharing Knowledge, Celebrating Identity: Community memory in a service culture. In D. Middleton & D. Edwards (Eds.), Collective remembering (pp. 169-189). London: Sage.

Pan, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (2003). Bridging communities of practice with information technology in pursuit of global knowledge sharing. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 12 (1), 71-88.

Paris Technology (n.d.) ParisTech graduate school homepage. Retrieved October 24, 2007 from: http://graduateschool.paristech.org/

Phipps, G. (2005, May 6). Turning Fantasy into a Reality that Helps Others: Lucifer Chu's obscure interest in fantasy novels ended up making him an unlikely millionaire. Taipei Times, p. 8. Retrieved October 21, 2007 from: http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2005/03/06/2003225764/print

Public Library of Science (n.d.). Public Library of Science homepage. Retrieved October 24, 2007 from: http://www.plos.org/

Rheingold, H. (2000). The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schwen, T. M., & Hara, N. (2003). Community of Practice: A metaphor for online design? The Information Society , 19(3). 257-270.

Smith, M., & Kollock, P. (Eds.). (1999). Communities in cyberspace. London: Routledge.

Thomas, A. (2005). Children Online: Learning in a virtual community of practice. E-Learning, 2(1), 27-38. Retrieved October 24, 2007 from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/elea.2005.2.1.3

Tufts University (n.d.). Tufts University’s OCW. Retrieved October 22, 2007 from: http://ocw.tufts.edu/

Utah State University (n.d.). Utah State University’s OCW homepage. Retrieved October 21, 2007 from: http://ocw.usu.edu

Wasko, M. M., & Faraj, S. (2000).‘It is What One Does’: Why people participate and help others in electronic communities of practice. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 9(2-3), 155-173.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (2004). Learning for a Small Planet: A research agenda. Retrieved July 15, 2007 from: http://www.learninghistories.nl/documents/learning%20for%20a%20small%20planet.pdf

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). A Guide to Managing Knowledge: Cultivating communities of practice. Boston, MA.: Harvard Business School Press.