J. B. Arbaugh

University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh

USA

While Garrison and colleagues’ (2000) Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework has generated substantial interest among online learning researchers, it has yet to be subjected to extensive quantitative verification or tested for external validity. Using a sample of students from 55 online MBA courses, the findings of this study suggest strong empirical support for the framework and its ability to predict both perceived learning and delivery medium satisfaction in online management education. The paper concludes with a discussion of potential implications for online management education researchers and those interested in further study of the CoI framework.

Keywords: community of inquiry framework; online MBA courses; learning outcomes

In spite of the explosion of empirical research on online learning effectiveness over the last decade (Sitzmann, Kraiger, Stewart, & Wisher, 2006; Tallent-Runnels, Thomas, Lan, Cooper, Ahern, Shaw, & Liu, 2006), the emergence of a dominant theoretical framework that explains online learning effectiveness has yet to occur. While there are several potential emerging models of online business education (e.g., Alavi & Leidner, 2001; Leidner & Jarvenpaa, 1995; Rungtusanatham, Ellram, Siferd, & Salik, 2004; Sharda, Romano, Lucca, Weiser, Scheets, Chung, & Sleezer, 2004), one that has attracted the most attention is the Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework developed by Garrison, Anderson and Archer (2000). Google Scholar shows that Garrison and colleagues’ initial article describing the framework has been cited in other works at least 260 times as of October 2007, making it by far the most cited article from the journal The Internet and Higher Education. However, while the CoI framework is gaining increasing attention among education scholars (Anagnostopoulos, Basmadjian, & McCrory, 2005; Arnold & Ducate, 2006; Meyer, 2004; Shea, 2006), studies that examine the framework’s generalizability to online learning in other disciplines is somewhat limited. Also, while the CoI framework has received extensive examination in qualitative studies (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2005; Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Heckman & Annabi, 2005; Oriogun, Ravenscroft, & Cook, 2005; Stodel, Thompson, & MacDonald, 2006), and individual components of the framework have been examined empirically (Arbaugh & Hwang, 2006; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Shea, Fredericksen, Pickett, & Pelz, 2003; Wise, Chang, Duffy, & del Valle, 2004), studies that empirically examine all components of the framework simultaneously are limited. Because of this relative lack of empirical research, studies that examine the relationship between any of the framework’s dimensions and learning outcomes are only now beginning to emerge (Shea, 2006; Shea, Li, & Pickett, 2006). Because of this relative lack of empirical research, presently there is little evidence available to consider whether there are significant relationships between any of the framework’s dimensions and course outcomes (Ho & Swan, 2007). In fact, one of the framework’s creators recently has suggested that this stream of research needs to move from early exploratory and descriptive studies toward rigorous empirical analysis (Garrison, 2007). Therefore, if the CoI framework is to gain legitimacy as a theory of online learning, we need more empirical studies to assess its explanatory power in fields beyond general education.

The purpose of this paper is to report on the results of a study that examines whether the CoI dimensions of social, teaching, and cognitive presence distinctively exist in management education e-learning environments, and whether and to what extent these dimensions are associated with perceived learning and delivery medium satisfaction in online MBA courses. By doing this, the paper provides initial insights into the empirical verification of the CoI framework and its potential for generalizability to online management education. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The first section of the paper describes the CoI framework and reviews recent studies on its three dimensions: social, cognitive, and teaching presence, and uses this literature to hypothesize relationships between these dimensions and student perceived learning and delivery medium satisfaction. The paper’s second section presents the development of the research sample of MBA students in online courses over a two-year period at a Midwestern U.S. university and describes the survey items used to measure the CoI dimensions. Next, the results section of the paper describes an exploratory factor analysis of the CoI measures and a regression analysis used to test the study’s hypotheses. Finally, the discussion section presents primary conclusions and contributions and potential implications of these findings for online management education instructors and researchers.

Garrison and colleagues (2000) developed the CoI framework to investigate how features of written language used in computer conferencing activities promote critical/ higher-order thinking. They contend that higher-order learning experiences are best conducted as a community of inquiry composed of teachers and learners (Lipman, 1991) requiring both the engagement of “real” persons and the demonstration of critical thinking to be successful. Their framework posits that effective online learning is a function of the interaction of three elements: teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence. The following section describes these three elements and develops hypotheses for each regarding their relationship to online course outcomes. Since it is the element that has been most recently conceptualized, teaching presence is discussed first and most extensively.

Garrison and colleagues (2000) contend that while interactions between participants are necessary in virtual learning environments, interactions by themselves are not sufficient to ensure effective online learning. These types of interactions need to have clearly defined parameters and be focused toward a specific direction, hence the need for teaching presence. They describe teaching presence as the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes. Anderson and colleagues (2001) conceptualized teaching presence as having three components: 1) instructional design and organization; 2) facilitating discourse (originally called “building understanding”), and 3) direct instruction. While recent empirical research may generate a debate regarding whether teaching presence has two (Shea, 2006) or three (Arbaugh & Hwang, 2006) components, the general conceptualization of this CoI element has been supported by subsequent research (Coppola, Hiltz, & Rotter, 2002; LaPointe & Gunawardena, 2004; Stein, Wanstreet, Calvin, Overtoom, & Wheaton, 2005).

Anderson and colleagues (2001) describe the design and organization aspect of teaching presence as the planning and design of the structure, process, interaction and evaluation aspects of the online course. Some of the activities comprising this category of teaching presence include re-creating Power Point presentations and lecture notes onto the course site, developing audio/video mini-lectures, providing personal insights into the course material, creating a desirable mix of and a schedule for individual and group activities, and providing guidelines on how to use the medium effectively. These are particularly important activities since clear and consistent course structure supporting engaged instructors and dynamic discussions have been found to be the most consistent predictors of successful online courses (Swan, 2002; 2003). Of the three components of teaching presence, this is the one most likely to be performed exclusively by the instructor. These activities are for the most part completed prior to the beginning of the course, but adjustments can be made as the course progresses (Anderson et al., 2001).

Anderson and colleagues (2001) conceptualize facilitating discourse as the means by which students are engaged in interacting about and building upon the information provided in the course instructional materials. This component of teaching presence is consistent with findings supporting the importance of participant interaction in online learning effectiveness in general and in management education in particular (Arbaugh, 2005b; Benbunan-Fich & Arbaugh, 2006; Sherry, Fulford, & Zhang, 1998). This role includes sharing meaning, identifying areas of agreement and disagreement, and seeking to reach consensus and understanding. Therefore, facilitating discourse requires the instructor to review and comment upon student comments, raise questions, and make observations to move discussions in a desired direction, keeping discussion moving efficiently, draw out inactive students, and limit the activity of dominating posters when they become detrimental to the learning of the group (Anderson et al., 2001; Brower, 2003; Coppola et al., 2002; Shea et al., 2003).

Anderson and colleagues (2001) contextualized direct instruction as the instructor provision of intellectual and scholarly leadership in part through the sharing of their subject matter knowledge with the students. They also contend that a subject matter expert and not merely a facilitator must play this role because of the need to diagnose comments for accurate understanding, injecting sources of information, and directing discussions in useful directions, scaffolding learner knowledge to raise it to a new level.

In addition to the sharing of knowledge by a content expert, direct instruction is concerned with indicators that assess the discourse and the efficacy of the educational process. Instructor responsibilities are to facilitate reflection and discourse by presenting content, using various means of assessment and feedback. Explanatory feedback is crucial. This type of communication must be perceived to have a high level of social presence/ instructor immediacy (Baker, 2004; Gorham, 1988; Richardson & Swan, 2003) to be effective. Instructors must have both content and pedagogical expertise to make links among contributed ideas, diagnose misperceptions, and inject knowledge from textbooks, articles, and Web-based materials.

The simultaneous roles of discussion facilitator and content expert within teaching presence goes beyond early contentions that online instructors needed merely to transition from a role of knowledge disseminator to interaction facilitator. Teaching presence contends that for online learning to be effective, instructors must play both roles (Arbaugh & Hwang, 2006). Considering that recent research in online management education suggests that extensive instructor engagement is necessary for positive learning outcomes (Eom, Wen, & Ashill, 2006; Marks, Sibley, & Arbaugh, 2005), it is reasonable to predict that teaching presence would influence learning in online MBA courses. Also, teaching presence’s emphasis on design and organization should positively influence student satisfaction with the Internet as a delivery medium. If there is no set of activities, no timeline, no protocol, no format for course materials and no evaluation criteria, chaos will ensue in the online environment (Berger, 1999; Hiltz & Wellman, 1997). Design and organization provide the context for which discourse and direct instruction have meaning. The results of recent online management education research that shows a strong relationship between course design and structural characteristics and delivery medium satisfaction (Arbaugh & Rau, 2007; Eom et al., 2006) suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Teaching presence will be positively associated with student perceived learning in web-based MBA courses.

Hypothesis 1b: Teaching presence will be positively associated with student satisfaction with the delivery medium for web-based MBA courses.

Social presence in online learning has been described as the ability of learners to project themselves socially and emotionally, thereby being perceived as “real people” in mediated communication (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997; Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976). Similar to teaching presence, social presence in virtual learning environments has been conceptualized as having three categories, which are open communication, group cohesion, and affective expression (Garrison, 2007). Affective expression specifically refers to mechanisms for injecting emotion into the environment in lieu of visual or oral cues, such as emoticons or parenthetical meta-linguistic cues such as “hmmm” or “yuk” (Gunawardena, 1995; Hiltz, 1994; Walther, 1992). Of the three types of presence included in the CoI framework, the role of social presence in educational settings has been the most extensively studied, both in online and face-to-face course settings (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997; Richardson & Swan, 2003; Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, & Archer, 2001; Walther, 1992).

Recent research on social presence in online learning also has focused on its role in facilitating cognitive development and critical thinking. To date, this research suggests that while social presence alone will not ensure the development of critical discourse in online learning, it is extremely difficult for such discourse to develop without a foundation of social presence (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005). A recent study on the effects of inter-personality in online learning by Beuchot and Bullen (2005) suggests that increased sociability of course participants leads to increased interaction, therefore implying that social presence is necessary for the development of cognitive presence. Anagnostopoulos and colleagues’ (2005) concept of inter-subjective modality provides further support for this premise. According to these authors, inter-subjective modality in the online environment occurs when a participant explicitly refers to another participant’s statement when developing their own post, thereby both connecting themselves to the other participant and laying the foundation for higher level inquiry. Other recent studies supporting the “social presence as foundation for cognitive presence” perspective include those by Molinari (2004), and Celani and Collins (2005).

Studies of student group cohesiveness and interaction on team effectiveness in online management education suggest a strong relationship between social presence and learning outcomes (Arbaugh, 2005b; Hwang & Arbaugh, 2006; Williams, Duray, & Reddy, 2006; Yoo, Kanawattanachai, & Citurs, 2002). This emerging research stream also suggests that activities that cultivate social presence also enhance the learner’s delivery medium satisfaction (Arbaugh & Benbunan-Fich, 2006). Collaborative activities allow learners greater opportunities for increased social presence and a greater sense of online community, which also tends to improve the socio-emotional climate in online courses (Richardson & Swan, 2003; Rovai, 2002). Positive social climates support more rapid mastery of the “hidden curriculum” of the technological aspects of distance education ( Anderson, 2002), resulting in increased satisfaction with both the learning process and the medium through which it is delivered (Arbaugh, 2004; Benbunan-Fich & Hiltz, 2003). These recent findings related to social presence in online graduate management education suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: Social presence will be positively associated with student perceived learning in web-based MBA courses.

Hypothesis 2b: Social presence will be positively associated with student satisfaction with the delivery medium for web-based MBA courses.

Garrison, Anderson, and Archer (2001) described cognitive presence as the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse, and argued that cognitive presence in online learning is developed as the result of a four phase process. These phases are: 1) a triggering event, where some issue or problem is identified for further inquiry; 2) exploration, where students explore the issue both individually and corporately through critical reflection and discourse; 3) integration, where learners construct meaning from the ideas developed during exploration; and then 4) resolution, where learners apply the newly gained knowledge to educational contexts or workplace settings. Garrison and colleagues (2001) proposed that the integration phase typically requires enhanced teaching presence to probe and diagnose ideas so that learners will move to higher level thinking in developing their ideas.

Of the three types of presence in the CoI framework, cognitive presence likely is the one most challenging to develop in online courses (Celani & Collins, 2005; Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Moore & Marra, 2005). Emerging research suggests a complementary relationship between teaching presence and cognitive presence. While social presence lays the groundwork for higher-level discourse, the structure, organization, and leadership associated with teaching presence creates the environment where cognitive presence can be developed. Garrison and Cleveland-Innes (2005) found that course design, structure, and leadership significantly influence the extent to which learners engage course content in a deep and meaningful manner. These findings suggest that the role of instructors in cultivating cognitive presence is significant, both in terms of how they structure the course content and participant interactions. Given the previous discussion of the consistency between findings regarding teaching presence and emerging online management education research, it is reasonable to expect that the complementarities between teaching presence and cognitive presence found in online general education also extend to online graduate management education, particularly since initial studies in such settings suggest that virtual learning environments can help produce enhanced cognitive knowledge (Alavi, Marakas, & Yoo, 2002; Yoo et al., 2002). Hence, the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Cognitive presence will be positively associated with student perceived learning in web-based MBA courses.

Hypothesis 3b: Cognitive presence will be positively associated with student satisfaction with the delivery medium for web-based MBA courses.

The sample for this study came from 55 of the 56 online courses conducted in the MBA program of a Mid-Western U. S. university over six semesters from February 2004 through January 2006. These courses were in subjects such as organizational behavior/ theory, international business, business strategy, human resource management, project management, operations management, information systems, finance, accounting, and professional development. Seventeen (n = 17) different instructors taught the courses included in the study. These instructors ranged from having no prior online teaching experience to having taught over forty previous online courses during the period of the study. This university was in a transition between course management software systems during the period of the study. Therefore, six of the courses in the first two semesters of the study were conducted using the Blackboard software platform, while subsequent courses were conducted using Desire to Learn (D2L). Both course management systems have synchronous and asynchronous interaction capability. The courses were distance learning classes with students taught primarily through asynchronous Web-based interactions, and 40 of the class sections had an on-site orientation meeting . Class sizes ranged from 7 to 49.

Data collection was completed in a two-step process. In the first step, students were emailed a survey during the final week of the course regarding their perceptions of the learning environment, course management system, instructor behaviors, the knowledge they acquired, and their satisfaction with the internet as the course delivery medium. The second step was conducted 7 to 10 days after the electronic survey was sent. In this step, students who had not responded to the electronic survey were mailed a paper copy of the original survey. In terms of numbers, 656 students provided useable responses, resulting in a response rate of 54.7 percent (656 of 1,200). The mean student age was 32.70(SD = 6.34), and 57 percent of the respondents were male.

Perceived student learning and satisfaction with the course delivery medium were the study’s dependent variables. These variables were derived by a factor analysis using a Varimax rotation of 11 items previously used to measure these variables, for which the two-factor solution explained 73.6 percent of the variance in the survey items. Perceived learning has been commonly used as a dependent variable in studies of online management education (Alavi et al., 2002; McGorry, 2003; Yoo et al., 2002). This measure was used because other studies have shown that using course grades in multi-disciplinary studies are subject to the limitations of inconsistent assignment across courses and instructors, and a relatively restricted range in courses at the graduate level (Arbaugh, 2005a; Rovai, 2002). Perceived learning was measured using six items adapted from Alavi (1994) and Arbaugh (2000) (coefficient alpha = .94).

Satisfaction with the delivery medium also often has been a dependent variable in studies of online learning (Alavi, Wheeler, & Valacich, 1995; Chidambaram, 1996; Eom et al., 2006). Further rationale for the use of this measure is that delivery medium satisfaction may influence a student’s likelihood to continue taking courses online (Arbaugh, 2000), and that it may be an indirect indicator of actual learning (Leidner & Fuller, 1997). Delivery medium satisfaction was measured using five items from Arbaugh’s (2000) scales (coefficient alpha = .87).

While the dimensions of the CoI framework have been examined via content analysis (Anderson et al., 2001; Garrison et al., 2001; Stodel et al., 2006), the survey-based measures that were adopted in this study allow for the use of a larger and wider sample in a relatively efficient manner. The scales for teaching presence (Course Design and Organization - 3 items; Facilitating Discourse - 3 items; and Direct Instruction - 4 items) were developed by Shea and colleagues (2003) in their study of teaching presence in the SUNY Learning Network. Eight items measuring social presence were adapted from measures used in Richardson and Swan’s (2003) study, which, in turn, were developed from Gunawardena and Zittle’s (1997), and Short and colleagues’ (1976) conceptualizations of the construct. While some survey-based measures of cognitive presence are now available (Garrison, Cleveland-Innes, & Fung, 2004) such measures were not publicly available at the beginning of this study. Therefore, four items were developed based on Garrison and colleagues’ (2001) conceptualization of cognitive presence. These items place particular focus on the final three (exploration, integration, and resolution) phases of construct since the first phase, the “triggering event”, often is expressed as part of teaching presence (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005). One item from Shea and colleagues’ (2003) measure of teaching presence, “ The instructor provided useful information from a variety of sources that helped me to learn ” was used to measure the “triggering event” phase of cognitive presence. All survey items were anchored on a 7-point scale ranging from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.”

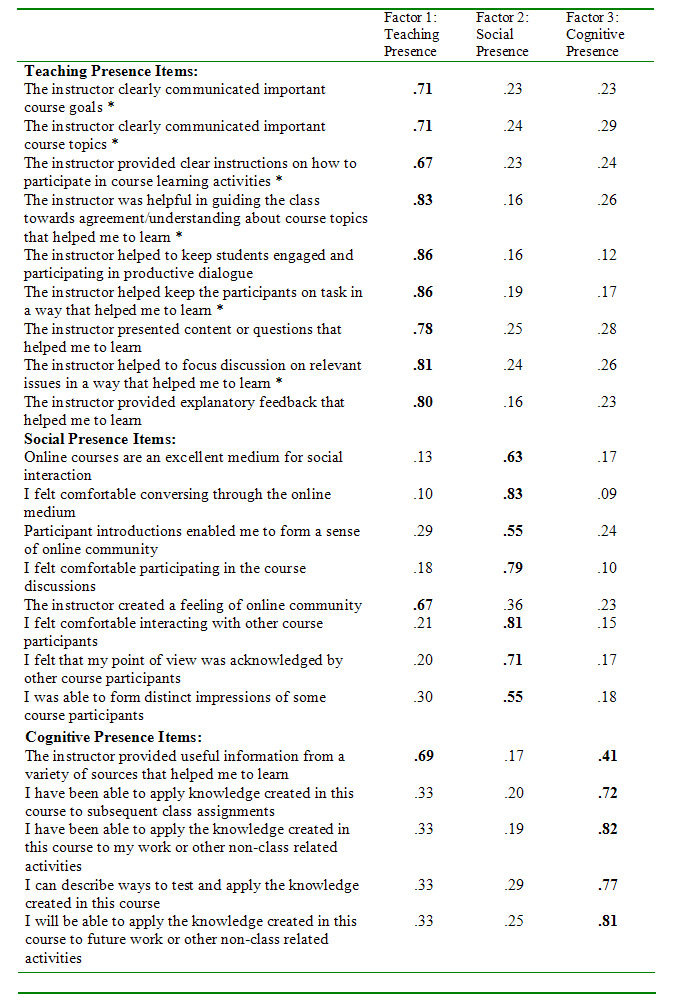

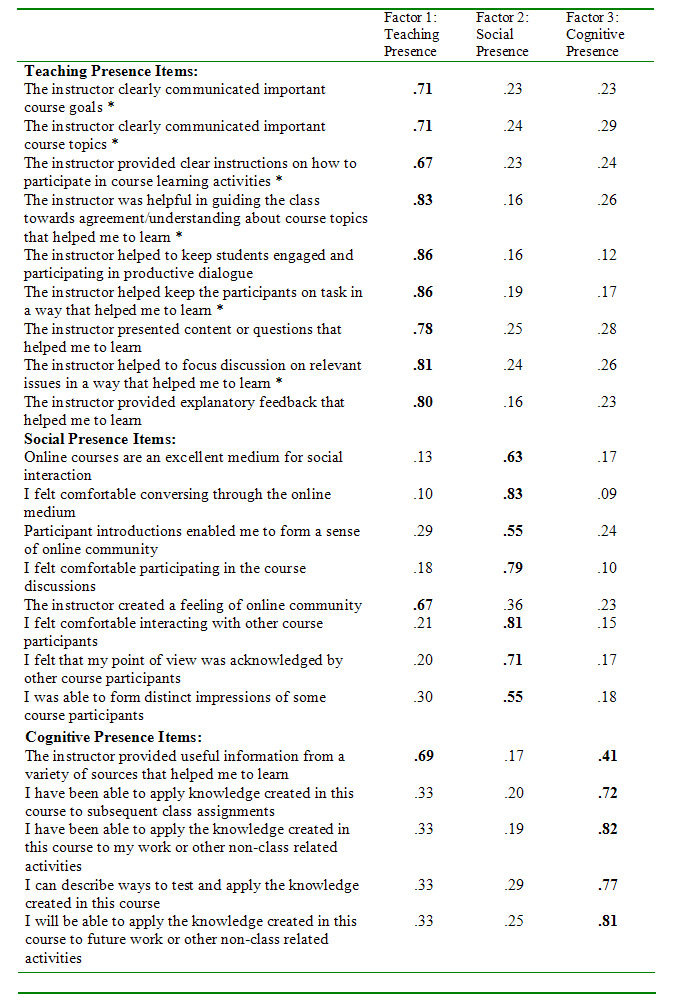

While survey-based measures for social presence are well established in previous research, valid and reliable measures of teaching presence can be best described as a work in progress (Arbaugh & Hwang, 2006; Shea, 2006; Shea et al., 2006). Furthermore, measures of cognitive presence are extremely limited. With the exception of Garrison and colleagues’ (2004) study, there are no known studies that simultaneously examine these three constructs. Therefore, for these reasons, as well as the relative newness of the CoI framework and the use of new measures for cognitive presence, the data was analyzed using exploratory factor analysis via principal components analysis using SAS’s Factor procedure with varimax rotation (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1992; Stevens, 2002). Cattell’s (1966) Scree test and theoretical grounding of the CoI framework indicated support for three factors, which collectively accounted for 67.4 percent of the variance in the survey items. The factors and their loadings from each of the survey items are presented in Table 1. As Table 1 shows, all factors have reliability alphas of .87 or higher, which is well above the recommended .7 for exploratory research (Nunnally, 1978). Using guidelines developed by Stevens (2002), the factors were interpreted using only survey items that loaded at .40 or higher.

Table 1. Factor loadings for CoI survey items (N = 656)

Because of their potential confounding effects in previous studies of Web-based courses in business education (Anstine & Skidmore, 2005; Klein, Noe, & Wang, 2006; Webb, Gill, & Poe, 2005; Williams et al., 2006), controls were established for class section size, student age, gender, weekly course website usage, and student prior experience with Web-based courses. Student Web-based course experience was measured by the number of prior Web-based courses taken by the student, and weekly course website usage was measured by the number of days a week the student logged onto the course site multiplied by the self-reported average number of minutes per session spent on the site. Since recent findings in online management education research suggests that instructor subject knowledge and online teaching experience influence outcomes in online courses (Arbaugh, 2005a; Arbaugh & Rau, 2007; Eom et al., 2006) both instructor online teaching and subject matter experience were controlled for by counting both the total number of Web-based courses and the number of total times the instructor had previously taught that particular course in classroom and/ or online settings for each course in the study. Potential time-related effects of a multi-semester study were controlled by coding the first semester in the study as 0 and then cumulatively coding each subsequent semester (second semester = 1, third semester = 2, etc.) (Arbaugh, 2005b). Finally, the number of credit hours and a dummy variable to measure whether acourse was required or elective (0 = elective, 1 = required) were used to control for course-level effects.

Results

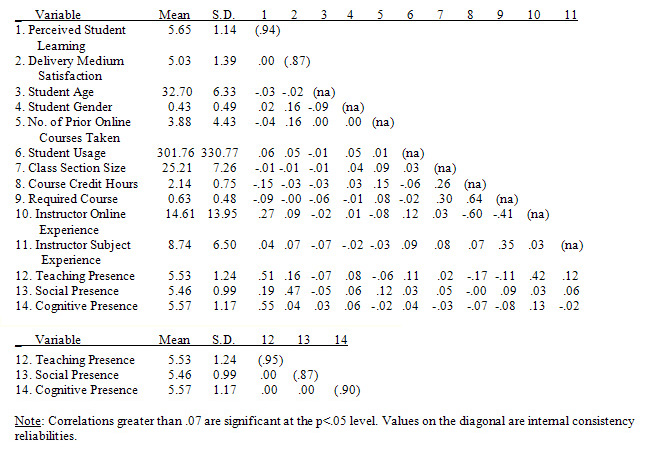

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, correlations, and inter-item reliabilities for each of the variables. While correlations above .07 are statistically significant, only 8 correlations are above .3. Also, variance inflation factors were less than 3 for all variables, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a major concern with this data (Hair et al., 1992). Both teaching presence and cognitive presence, however, are relatively highly correlated with perceived learning (r = .51 and .55 respectively). While these are rather high correlations, variance inflation for these variables was particularly low (1.26 and 1.04 respectively). Recent research also has found the dimensions of teaching presence to be strongly associated with perceived learning (Shea et al., 2006).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlations

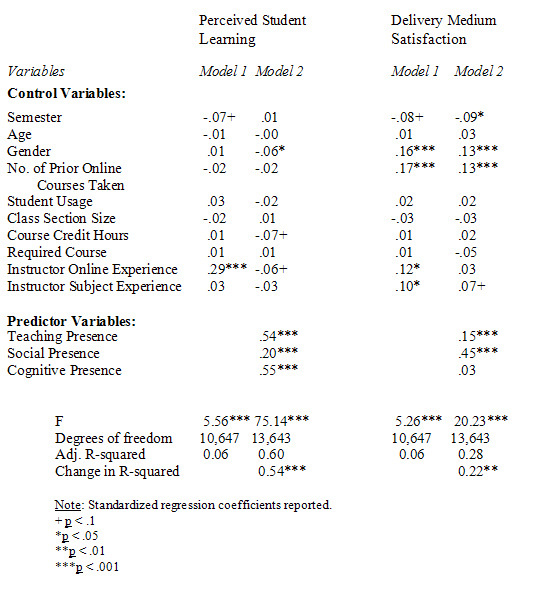

Table 3 presents the results of hierarchical regression analyses on perceived learning and delivery medium satisfaction respectively. The regression coefficients for each of the three types of presence will be used to test the study’s hypotheses.

Table 3. Results of regression analyses on dependent variables ( N = 656)

Hypotheses 1a and 1b predicted that teaching presence would be positively associated with perceived student learning and delivery medium satisfaction respectively. However, while both hypotheses are strongly supported (p<.001), teaching presence is a much stronger predictor of perceived learning (b = .54) than of delivery medium satisfaction (b = .15). Hypotheses 2a and 2b predicted that social presence would be positively associated with perceived student learning and delivery medium satisfaction respectively. Again, both hypotheses are strongly supported (p<.001). For these hypotheses, however, social presence is a much stronger predictor of delivery medium satisfaction (b = .45) than of perceived learning (b = .20). While cognitive presence is a strong predictor of perceived learning (b = .55), it is not a significant predictor of delivery medium satisfaction, and therefore Hypothesis 3a is supported but not Hypothesis 3b.

The fact that elements of a relatively new theoretical framework not only could be reliably measured, but uniquely account for 54 percent of the variance in student perceived learning is noteworthy. Although the findings of this study need to be supported by future research, they do suggest that the CoI framework may be a powerful yet parsimonious predictor of perceived learning in online MBA courses. This should be cause for encouragement for both researchers interested in the CoI framework and those interested specifically in online management education. The study contributes to the literature on the CoI framework in that it quantitatively examines all three types of presence and their relationships to course outcomes using a multi-course sample large enough to provide appropriate statistical power. Compared to other recent studies, the findings suggest a highly reliable yet relatively efficient set of survey items for measuring the CoI framework, and researchers certainly should consider incorporating them into future studies.

While the study’s design does not allow for the testing of a sequential model, the findings that teaching presence and cognitive presence were the stronger predictors of perceived learning support Garrison and Cleveland-Innes’ (2005) contention that social presence is a necessary, but not sufficient condition, for student learning in the online environment. The findings of this study suggest that while social presence is important, teaching and cognitive presences are the primary and the complementary drivers of such learning. Given recent research results indicating the importance of instructors in virtual learning environments (Benbunan-Fich & Arbaugh, 2006; Brower, 2003; Coppola et al., 2002; Peltier, Schibrowsky, & Drago, 2007 ), the results of this study provide additional clarity regarding the nature of the instructor’s role and its importance.

More specific to the domain of online management education research, the findings of the study build upon emerging frameworks of online course effectiveness. Considering that the statistical significance of prior instructor online teaching experience as a predictor of perceived learning was almost completely mitigated by the introduction of teaching, social, and cognitive presence, the strength of the relationship of these factors to perceived learning suggests that they may be stronger predictors than are technology or pedagogical characteristics for offsetting instructor experience effects in online management education (Anstine & Skidmore, 2005; Arbaugh, 2005b). The study also builds upon Arbaugh’s (2005b) recent study by clarifying the nature of participant interaction necessary for a successful online course. Rather than merely engaging other participants for engagement’s sake, the instructor’s interaction should be of a nature that intentionally pushes students to think deeply and in an integrative manner, allowing for ideas to become further refined as a result of engagement with other participants (Brower, 2003). Students, in turn, should be seeking and discussing potential opportunities to apply this newly created and acquired knowledge to their own educational or organizational situations.

While the framework is a stronger predictor of perceived learning than delivery medium satisfaction, the fact that the CoI framework uniquely explains 22 percent of the variance in delivery medium satisfaction still is noteworthy, particularly considering that the framework was developed to explain learning effectiveness in virtual environments without consideration of other online course outcomes. This relative lack of strength of relationship, however, warrants further explanation. The most noteworthy difference between analyses of the two dependent variables is their relationship with cognitive presence. While it was a positive predictor, cognitive presence was not a statistically significant a predictor of delivery medium satisfaction. There are at least two potential explanations for this non-significant relationship. First, since the measures for cognitive presence in this study focus more on its integration and resolution aspects, the role and significance of triggering events within the delivery medium likely are not fully captured in this study. This suggests that researchers should develop more robust measures of this construct in future studies (Garrison, 2007). Another benefit of further refinement of the measures for cognitive presence is that those efforts likely would reduce the possibility of multicolinearity between measures of cognitive presence and measures of student learning. It is possible that the post-course application orientation of the measures for cognitive presence and the post-course evaluation of student learning may have influenced the relationship between cognitive presence and perceived learning. Cognitive presence, however, has been described as “the element within a community of inquiry which reflects the focus and success of the learning experience” (Vaughan & Garrison, 2005, p. 8). The combination of this conceptualization and low variance inflation suggests that the correlation between cognitive presence and perceived learning appears to be one of natural association rather than statistical artifact.

Second,the CoI framework only considers course conduct and participant behaviors; whereas recent research suggests that other characteristics, such as characteristics of the course management system, disciplinary characteristics, and the number and variety of course assignments may be more significant predictors of delivery medium satisfaction in technology-mediated management education (Arbaugh, 2005b; Arbaugh & Rau, 2007; Webb et al., 2005). Future studies should incorporate these variables when considering the CoI-delivery medium satisfaction relationship.

Finally, it is possible that learning curve effects of adopting the course management system could adversely influence students’ ability to cultivate cognitive presence. Recent technology-mediated management education research suggests that relatively simpler and/ or more familiar technologies may produce more significant cognitive gains in adult learners (Alavi et al., 2002), and that the learning curve associated with learning a new technology may result in frustration for newer students, or at minimum, increase the time and attention they give to interacting about the technology (Anderson, 2002; Alavi et al., 2002; Yoo et al., 2002). Considering that prior student experience with online learning was one of the strongest predictors of delivery medium satisfaction in the study, this seems to be a reasonable explanation for the lack of relationship. Also, while there is no evidence available to suggest that D2L is a more complex course management system than Blackboard, it is possible that the transition to this learning system during the study may have influenced these findings. These conditions, however, also may help to explain why social presence was the strongest CoI predictor of delivery medium satisfaction. If newer online students were trying to learn how to learn online and more experienced online students were trying to learn the course management system, expressing confusion and/ or frustration over the process of learning the technology to their group members or fellow classmates may have enhanced their social presence and even increased group cohesiveness (Williams et al., 2006). These possible explanations suggest that the relationship between social presence and delivery medium satisfaction merits further attention in future studies.

Of course, this study’s findings must be interpreted in light of its limitations. In addition to the previously mentioned issues regarding the operationalization of cognitive presence there are three that are particularly noteworthy. First, in addition to creating some new survey items to measure constructs that have not been widely operationalized, the study incorporated measures of variables developed in different research settings that have not been used together previously. This may explain why some survey items loaded on different constructs than those they were designed to measure. Also, while variance inflation factors of the variables were quite low, it is possible that wording of these items may be capturing similar constructs when combined into a single instrument. We hope that future researchers will build upon this effort to develop measures of the CoI elements and criterion variables that are reliable, efficient, and distinct. Second, although the study helps to answer recent calls for multi-discipline, multi-semester studies in online management education (Marks et al., 2005) it is based upon the findings at a single institution. Third, the students in these courses were enrolled in the university’s regular MBA program and were taking these courses along with courses in physical classrooms. This may prevent the study’s findings from being generalizable to MBA programs that are offered completely online or to online undergraduate programs.

In spite of these limitations, the study carries several potential implications for management educators, management education researchers, and those with broader research interest in the CoI framework. For management educators, one clear implication is that lack of online teaching experience does not necessarily have to prevent one from becoming an effective online instructor. Novice instructors can achieve positive course outcomes by engaging students in online discussion and encouraging them to do likewise (Arbaugh, 2005b; Arbaugh & Rau, 2007; Brower, 2003). For specific tips regarding how to frame those interactions to reflect CoI principles, consulting Garrison and Anderson’s (2003) recent text would be a good start.

For management education researchers, the findings suggest that the CoI framework could be a useful building block upon which to develop a theory of online management education. Developing discipline-specific theories has long been a challenge for management education researchers (Lemak, Shin, Reed, & Montgomery, 2005). While building such a theory based upon the CoI would again require management education researchers to borrow from other disciplines, they also may be able to integrate characteristics unique to the discipline such as characteristics of the course material or prior student experiences with the course concepts into such a theoretical framework (Arbaugh, 2005a; Nadkarni, 2003).

Another potentially interesting direction for management education researchers would be to test the generalizability of the CoI by examining its predictive ability in undergraduate online settings. Initial studies of the CoI framework in undergraduate business settings suggest that the nature and direction of student interaction is somewhat different between classroom and online course offerings, with students engaging each other in more frequent and higher level dialogue of longer duration in online discussions, while most classroom discussions tended to be instructor led and centered (Heckman & Annabi, 2005). However, since Heckman and Annabi’s (2005) study design did not allow them to assess the relationship between CoI elements and course outcomes, this is still an area that merits additional research.

Finally, this study has implications for those interested in further study of the CoI framework. The development of a preliminary quantitative measure of cognitive presence should merit particular attention and attempts at refinement. By addressing the later stages of the critical inquiry process, the items developed to measure cognitive presence for this study help address Garrison’s (2007) recent call for a “step forward” in research on this element. There are at least two possible explanations for the findings in this study pertaining to cognitive presence that merit further research. First, while some approaches to online learning research criticize using data collected after the learning experience is completed (Hodgson & Watland, 2004); such an approach may be advantageous for studying cognitive presence because it incorporates the possibility that learners might need time to complete the higher-order phases of the critical inquiry process. Therefore, techniques typically used to assess cognitive presence such as transcript analysis (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Heckman & Annabi, 2005) may not completely capture the cognitive inquiry process and therefore should be supplemented with some sort of data collection at the end of the course. Second, the findings also suggest the possibility that characteristics of degree program and level of study might influence the occurrence of cognitive presence in online learning. While the nature of assignments and discussion questions provided in e-learning environments can encourage progression to higher stages of cognitive inquiry (Arnold & Ducate, 2006; Heckman & Annabi, 2005; Meyer, 2004), learner contexts also may be important in promoting inquiry. Online MBA courses targeted at students that have full-time professional positions may draw participants that can readily identify experiences to which they can apply higher level cognitive processes, where this may not be the case in learning environments such as community college or undergraduate level general education courses.

In addition to providing further quantitative verification of the CoI constructs, the comparatively large amount of unexplained variance in delivery medium satisfaction from this study suggest that CoI researchers should consider examining both the relationship of the CoI to course outcomes such as learner and/ or instructor satisfaction (Hartman, Dziuban, & Moskal, 2000; Hiltz & Shea, 2005) and the nature of the relationship between the CoI dimensions and other possible predictors of online course outcomes. For example, the items used in this study should allow for more robust testing of how the CoI elements coexist with, and/ or moderate the effects of other variables associated with online learning outcomes. Along with possibly examining relationships between the elements of the framework, some other variables that researchers should consider studying in concert with the CoI elements include the course or subject matter (Arbaugh, 2005a; Wallace, 2002), the software used to deliver the course (Arbaugh, 2005b; Martins & Kellermanns, 2004), characteristics of learners and/ or instructors (Hiltz & Shea, 2005; Peltier et al., 2007) and how the use of virtual teams might either enhance or impede the relationships between the three types of presence (Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999; Williams et al., 2006).

This paper reported on an empirical verification of the elements of the CoI framework, which found empirically distinct measures of social, cognitive, and teaching presence. The CoI framework, in turn, was found to be a significant predictor of both perceived student learning and delivery medium satisfaction in online MBA courses. These findings suggest that the CoI is a potentially powerful theoretical framework for explaining online learning effectiveness. The results of the study strongly support Garrison’s (2007) recent conclusion that CoI research now needs to move beyond exploratory descriptive studies to the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods. This state of affairs presents abundant opportunities for future online learning researchers.

Alavi, M., Marakas, G. M., & Yoo, Y. (2002). A comparative study of distributed learning environments on learning outcomes. Information Systems Research, 13, 404-415.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Research Commentary: Technology-mediated learning – A call for greater depth and breadth of research. Information Systems Research, 12(1), 1-10.

Alavi, M., Wheeler, B. C., & Valacich, J. S. (1995). Using IT to Re-Engineer Business Education: An exploratory investigation of collaborative telelearning. MIS Quarterly, 19(3), 293-312.

Alavi, M. (1994). Computer-Mediated Collaborative Learning: An empirical evaluation. MIS Quarterly, 18(2), 159-174.

Anagnostopoulos, D., Basmadjian, K. G., & McCrory, R. S. (2005). The decentered teacher and the construction of social space in the virtual classroom. Teachers College Record, 107, 1699-1729.

Anderson, T. (2002). The hidden curriculum of distance education. Change, 33(6), 28-35.

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2). http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/v5n2/v5n2_anderson.asp

Anstine, J., & Skidmore, M. (2005). A small sample study of traditional and online courses with sample selection adjustment. Journal of Economic Education, 36, 107-127.

Arbaugh, J. B., & Rau, B. L. (2007). A study of disciplinary, structural, and behavioral effects on course outcomes in online MBA courses. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 5(1), 63-93.

Arbaugh, J. B., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2006). An investigation of epistemological and social dimensions of teaching in online learning environments. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(4), 435-447.

Arbaugh, J. B., & Hwang, A. (2006). Does “teaching presence” exist in online MBA courses? The Internet and Higher Education, 9(1), 9-21.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2005a). How much does “subject matter” matter? A study of disciplinary effects in on-line MBA courses. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(1), 57-73.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2005b). Is there an optimal design for on-line MBA courses? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 135-149.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2004). Learning to Learn Online: A study of perceptual changes between multiple online course experiences. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(3), 169-182.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2000a). Virtual classroom characteristics and student satisfaction in internet-based MBA courses. Journal of Management Education, 24(1), 32-54.

Arnold, N., & Ducate, L. (2006). Future foreign language teachers’ social and cognitive collaboration in an online environment. Language Learning & Technology, 10(1): 42-66. http://llt.msu.edu/vol10num1/pdf/arnoldducate.pdf

Baker, J. D. (2004). An investigation of relationships among instructor immediacy and affective and cognitive learning in the online classroom. The Internet and Higher Education, 7, 1-13.

Benbunan-Fich, R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2006). Separating the effects of knowledge construction and group collaboration in web-based courses. Information & Management, 43(6), 778-793.

Benbunan-Fich, R., & Hiltz, S. R. (2003). Mediators of the effectiveness of online courses. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 46(4), 298-312.

Beuchot, A., & Bullen, M. (2005). Interaction and interpersonality in online discussion forums. Distance Education, 26(1), 67-87.

Berger, N. S. (1999). Pioneering Experiences in Distance Learning: Lessons learned. Journal of Management Education, 23(6), 684-690.

Brower, H. H. (2003). On Emulating Classroom Discussion in a Distance-delivered OBHR Course: Creating an on-line community. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2(1), 22-36.

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245-276.

Celani, M. A. A., & Collins, H. (2005). Critical thinking in reflective sessions and in online interactions. AILA Review, 18, 41-57.

Chidambaram, L. (1996). Relational development in computer-supported groups. MIS Quarterly, 20(2), 143-163.

Coppola, N. W., Hiltz, S. R., & Rotter, N. G. (2002). Becoming a Virtual Professor: Pedagogical roles and asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(4), 169-189.

Eom, S. B., Wen, H. J., & Ashill, N. (2006). The Determinants of Students’ Perceived Learning Outcomes and Satisfaction in University Online Education: An empirical investigation. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 4(2), 215-235.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72.

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133-148.

Garrison, D. R., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Fung, T. (2004). Student role adjustment in online communities of inquiry: Model and instrument validation. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 8(2). http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/v8n2/v8n2_garrison.asp

Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-Learning in the 21 st Century: A framework for research and practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7-23.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical Inquiry in a Text-based Environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Gorham, J. (1988). The relationship between verbal teacher immediacy behaviors and student learning. Communication Education, 37(1), 40-53.

Gunawardena, C. & Zittle, F. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer mediated conferencing environment. American Journal of Distance Education, 11(3), 8-26.

Gunawardena, C. N. (1995). Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer teleconferences. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 1(2/3), 147-166.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1992). Multivariate Data Analysis(3 rd ed.). New York: MacMillan.

Hartman, J., Dziuban, C., & Moskal, P. (2000). Faculty Satisfaction in ALNs: A dependent or independent variable? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 4(3). http://www.alnresearch.org/JSP/papers_frame_1.jsp

Heckman, R., & Annabi, H. (2005). A content analytic comparison of learning processes in online and face-to-face case study discussions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(2). http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue2/heckman.html

Hiltz, S. R., & Shea, P. (2005). The student in the online classroom. In S. R. Hiltz & R. Goldman (Eds.) Learning Together Online: Research on asynchronous learning networks (pp. 145-168). Mahwah, NJ.: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

Hiltz, S. R., & Wellman, B. (1997). Asynchronous learning networks as a virtual classroom. Communications of the ACM, 40(9), 44-49.

Hiltz, S. R. (1994). The Virtual Classroom: Learning without limits via computer networks. Norwood, NJ.: Ablex.

Ho, C.-H., & Swan, K. (2007). Evaluating Online Conversation in an Asynchronous Learning Environment: An application of Grice’s cooperative principle. The Internet and Higher Education, 10(1), 3-14.

Hodgson, V., & Watland, P. (2004). Researching networked management learning. Management Learning, 35(2), 99-116.

Hwang, A., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2006). Virtual and Traditional Feedback-seeking Behaviors: Underlying competitive attitudes and consequent grade performance. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 4(1), 1-28.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., & Leidner, D. E. (1999). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science, 10(6), 791-815.

Klein, H. J., Noe, R. A., & Wang, C. (2006). Motivation to Learn and Course Outcomes: The impact of delivery mode, learning goal orientation, and perceived barriers and enablers. Personnel Psychology, 59, 665-702.

LaPointe, D. K., & Gunawardena, C. N. (2004). Developing, testing, and refining a model to understand the relationship between peer interaction and learning outcomes in computer-mediated conferencing. Distance Education, 25(1), 83-106.

Leidner, D. E., & Fuller, M. (1997). Improving student learning of conceptual information: GSS-supported collaborative learning vs. individual constructive learning. Decision Support Systems, 20(2), 149-163.

Leidner, D. E., & Jarvenpaa, S. L. (1995). The use of Information Technology to Enhance Management School Education: A theoretical view. MIS Quarterly, 19(3), 265-291.

Lemak, D. J., Shin, S. J., Reed, R., & Montgomery, J. C. (2005). Technology, Transactional Distance, and Instructor Effectiveness: An empirical investigation. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 150-159.

Lipman, M. (1991). Thinking in education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marks, R. B., Sibley, S., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2005). A structural equation model of predictors for effective online learning. Journal of Management Education, 29 (4), 531-563.

Martins, L. L., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2004). A model of business school students’ acceptance of a web-based course management system. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(1), 7-26.

McGorry, S. Y. (2003). Measuring quality in online programs. The Internet and Higher Education, 6, 139-157.

Meyer, K. A. (2004). Evaluating Online Discussions: Four different frames of analysis. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 8(2), 101-114.

Molinari, D. L. (2004). The role of social comments in problem-solving groups in an online class. American Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 89-101.

Moore, J. L., & Marra, R. M. (2005). A comparative analysis of online discussion participation protocols. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 38(2), 191-212.

Nadkarni, S. (2003). Instructional Methods and Mental Models of Students: An empirical investigation. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 2(4), 335-351.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2 nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oriogun, P. K., Ravenscroft, A., & Cook, J. (2005). Validating an approach to examining cognitive engagement in online groups. American Journal of Distance Education, 19(4), 197-214.

Peltier, J. W., Schibrowsky, J. A., & Drago, W. (2007). The Interdependence of the Factors Influencing the Perceived Quality of the Online Learning Experience: A causal model. Journal of Marketing Education, 29(2), 140-153.

Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1). http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/v7n1/index.asp

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Methodological issues in the content analysis of computer conference transcripts. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 12(1), 8-22.

Rovai, A. P. (2002). Development of an instrument to measure classroom community. The Internet and Higher Education, 5(3), 197-211.

Rungtusanatham, M., Ellram, L. M., Siferd, S. P., & Salik, S. (2004). Toward a typology of business education in the internet age. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 2(2), 101-120.

Sharda, R., Romano, N. C. Jr., Lucca, J. A., Weiser, M., Scheets, G., Chung, J.-M., & Sleezer, C. M. (2004). Foundation for the study of computer-supported collaborative learning requiring immersive presence. Journal of Management Information Systems, 20(4), 31-63.

Shea, P. J., (2006). A study of students’ sense of learning community in online learning environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 10(1). http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v10n1/v10n1_4shea_member.asp

Shea, P., Li, C. S., & Pickett, A. (2006). A study of teaching presence and student sense of learning community in fully online and web-enhanced college courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 9(3), 175-190.

Shea, P. J., Fredericksen, E. E., Pickett, A. M., & Pelz, W. E. (2003). A preliminary investigation of “teaching presence” in the SUNY learning network. In J. Bourne & Janet C. Moore (Eds.), Elements of Quality Online Education: Into the mainstream, 4, (pp. 279-312). Needham, MA.: Sloan-C.

Sherry, A. C., Fulford, C. P., & Zhang, S. (1998). Assessing Distance Learners’ Satisfaction with Instruction: A quantitative and a qualitative measure. American Journal of Distance Education, 12(3), 4-28.

Short, J., Williams, E. & Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunication. London: Wiley.

Sitzmann, T., Kraiger, K., Stewart, D., & Wisher, R. (2006). The Comparative Effectiveness of Web-based and Classroom Instruction: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 59(3), 623-664.

Stein, D. S., Wanstreet, C. E., Calvin, J., Overtoom, C., & Wheaton, J. E. (2005). Bridging the transactional distance gap in online learning environments. American Journal of Distance Education, 19(2), 105-118.

Stevens, J. P. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (4 th ed.) Mahwah, NJ.: Erlbaum.

Stodel, E. J., Thompson, T. L., & MacDonald, C. J. (2006). Learners’ Perspectives on What is Missing from Online Learning: Interpretations through the community of inquiry framework. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 7(3). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/325/743

Swan, K. (2003). Learning effectiveness: What the research tells us. In J. Bourne & J. C. Moore (Eds), Elements of Quality Online Education: Practice and direction, 3, (pp. 13-45). Needham, MA.: Sloan Consortium.

Swan, K. (2002). Building Learning Communities in Online Courses: The importance of interaction. Education Communication and Information, 2(1), 23-49.

Tallent-Runnels, M. K., Thomas, J. A., Lan, W. Y. Cooper, S., Ahern, T. C., Shaw, S. M., & Liu, X. (2006). Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 93-135.

Vaughan, N., & Garrison, D. R. (2005). Creating cognitive presence in a blended faculty development community. The Internet and Higher Education, 8(1), 1-12.

Wallace, R. M. (2002). Online Learning in Higher Education: A review of research on interactions among teachers and students. Education, Communication, and Information, 3(2), 241-280.

Walther, J. (1992). Interpersonal Effects in Computer Mediated Interaction: A relational perspective. Communication Research, 19(1), 52-90.

Webb, H. W., Gill, G., & Poe, G. (2005). Teaching with the Case Method Online: Pure versus hybrid approaches. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 3, 223-250.

Williams, E. A., Duray, R., & Reddy, V. (2006). Teamwork Orientation, Group Cohesiveness, and Student Learning: A study of the use of teams in online distance education. Journal of Management Education, 30(4), 592-616.

Wise, A., Chang, J., Duffy, T., & del Valle, R. (2004). The effects of teacher social presence on student satisfaction, engagement, and learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 31, 247-271.

Yoo, Y., Kanawattanachai, P., & Citurs, A. (2002). Forging into the Wired Wilderness: A case study of a technology-mediated distributed discussion-based class. Journal of Management Education, 26(2), 139-163.