Volume 22, Number 1

Dr. Aakash Kamble1, Dr. Ritika Gauba2, Ms. Supriya Desai3, and Dr. Devidas Golhar4

1Indian Institute of Management Jammu, India, 2Independent Consultant, 3Indira Global Business School, Pune, India, 4Marathwada Mitra Mandal’s College of Commerce, Pune, India

Online learning environments (OLE) continue to expand due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the transition of a majority of educational institutions and universities worldwide from traditional classroom settings to online learning methods. The purpose of this study was to understand the perceptions of learners at a university in India toward the sudden transition from traditional face-to-face learning to an instructor-led OLE due to the pandemic-induced lockdown enforced across India in March 2020. Using a qualitative case study approach, structured interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams with 35 learners from Savitribai Phule Pune University, a large public university in India. Interviews comprised eight open-ended questions, which were validated by experts. Results indicate that learners accepted the transition toward the OLE. Five key themes arose from the interview data: accessibility and comfort, Internet connectivity, OLE effectiveness, course content, and interactions between students and instructors. The study provides insights to the researchers with the emergent themes from the research. Also, it carries practical implications concerning implications regarding infrastructure readiness for remote learners, acceptance, and adoption of OLEs by faculty instructors, organizational support, and facilitating conditions.

Keywords: online learning environment, OLE, learner perceptions, COVID-19, pedagogical issues, learning dynamics, India

The COVID-19 pandemic has led a majority of universities/educational institutions across the world to switch to online learning pedagogies. Nationwide lockdowns, which have been imposed in many countries, have resulted in the closure of university and college campuses and a transition toward online learning. Beginning in March 2020, many countries including India have practiced strict lockdown measures. India imposed a complete lockdown on March 24, 2020 (Gettleman & Schultz, 2020; Press Information Bureau, 2020), which resulted in the closure of educational institutions, universities, and colleges across the country, significantly impacting academic activity (Sharma, 2020). As Sharma (2020) asserts, the pandemic is paving the way for a paradigm shift in the Indian education system, with the accelerated adoption of digital technology. Some experts in India consider online education a contingency measure and not a long-term strategy (Agha, 2020). Academic institutions are challenged to adapt to changing demands in the short term, while maintaining the effectiveness of session delivery.

As businesses and the economy have been affected by the pandemic (Romei, 2020; Walker, 2020), so too has the education community (Alexander & Kwatra, 2020; John et al., 2020). The education sector has been required to transition to an online learning environment (OLE) to meet learner needs and ensure the continuity of curriculum and learning processes. The transition to OLEs has not been without challenges, as many institutions and learners depend on the availability of online learning platforms. Understanding OLEs plays a crucial role in delivering quality education and enhancing learners’ knowledge. The quality of OLEs involves various factors, including Internet connectivity, access to technology, infrastructure to conduct sessions, participation and interaction of learners and faculty instructors.

According to Hofmann (2002), online learning has gained increased importance due to the availability and accessibility of Internet technologies. Learning environments differ in their design and execution depending on learning objectives, target audience, access (physical, online, and/or both), and content type (Moore et al., 2011). Based on delivery method, the most popular learning environments are distance learning (Keegan, 2013; King et al., 2001; Moore, 1990), e-learning (Nichols, 2003; Tavangarian et al., 2004; Triacca et al., 2004), and online learning (Carliner, 2004; Lowenthal et al., 2009; Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005). As an instructional delivery system, distance learning offers learners the opportunity to participate in courses and programs from remote locations with the help of Internet technology. Distance learning opportunities have had a profound impact on beliefs about learning and teaching (Zapalska & Brozik, 2006). OLE can be instructor-led, self-paced, or self-directed depending on the delivery method (Moore, et al., 2011). In this study, the researchers focused on instructor-led OLE.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the importance of technology and virtual learning in education. While OLEs provide learners with numerous benefits, the sudden shift to a virtual environment due to the pandemic requires detailed study. The purpose of this study was to understand the perceptions and concerns of learners at Savitribai Phule Pune University, India, who are accustomed to traditional face-to-face learning, toward the sudden transition to online learning in March 2020 due to the pandemic, as well the impact of this transition on their learning. The authors addressed the following research question, what is traditional learners’ perception of online learning and what is its acceptability in India, in the context of the shift to OLEs due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

OLEs have been described as access to learning experiences through the use of technology (Benson, 2002; Carliner, 2004; Conrad, 2002). Dhawan (2020) defines online learning as “learning experiences in synchronous or asynchronous environments using different devices (e.g., mobile phones, laptops, etc.) with Internet access”. Current literature focuses on the benefits of online learning platforms where learners can access classrooms from anywhere. Previous studies have also identified the benefits of OLEs from the learners’ perspective (Chakraborty & Nafukho, 2014). Benefits of OLEs include enabling participation from across the world (Baker et al., 2009); improving computer skills due to the computer-mediated classes (Robinson & Hullinger, 2008); facilitating critical thinking and practical application of knowledge (Chen, 2014); and providing opportunities for use of higher-order skills, such as problem-solving and collaboration (Duderstadt et al., 2002).

Although technological innovations have created diverse options for OLEs (Amirault, 2015), the shift from the familiar traditional face-to-face learning environment poses challenges to the instructor as well as the learner due to the complex nature of the OLE (Chakraborty & Nafukho, 2014). Researchers have argued that online and distance learning environments are not adequate in developing learners’ generic competencies, a primary concern for educators (Gvaramadze, 2012). Furthermore, learners interact and engage differently in virtual learning environments compared with face-to-face settings, which alters their learning outcomes (Harris & Nikitenko, 2014). Instructors’ reduced interaction with learners and the lack of immediate feedback and response complicate the situation (Littlefield, 2018). Studies have emphasized that OLEs require a different pedagogy and set of skills from traditional classrooms (Boling et al., 2012).

Recent studies in the United States concerning the shift to online and digital learning platforms, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, focus on schools (Reich et al., 2020), the use of online learning to complement traditional learning modes (Barboni, 2019), the use of flipped classrooms, online practice sessions, and teleconferencing for resident medical students (Chick et al., 2020), and best practices for developing courses using OLEs (Sun & Chen, 2016). Educators in developing countries are faced with the necessity to transition to online teaching with minimal or no training. Furthermore, classroom sizes in developing countries are generally larger than in developed countries, and OLEs make classroom monitoring and communication with all learners challenging. In India the situation is particularly difficult due to the large number of learners and inadequate technological and communication infrastructure. The prevalence of the Internet in India has grown over the years, but Internet speed and connectivity remain unreliable with fluctuations occur depending on the area and region. Furthermore, both learners and instructors lack the laptops, printers, Webcams, and speakers required for online learning.

The study adopted a qualitative case study approach (Johnson & Christensen, 2019), to explore the phenomenon based on practical real-life scenarios (Merriam, 1998). The study focused on the experiences of learners in the transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic and the closure of all educational activities across India.

Participants in this study were students pursuing a master’s degree in business administration at a business school affiliated with Savitribai Phule Pune University, a public university in the city of Pune, the second-largest city in the state of Maharashtra and the eighth-most populous city in India. All participants studied full-time and were not employed while enrolled in the program. At the time of the study, the learners were in the second of four semesters in the program. With the enforcement of a lockdown in March 2020 across India due to the pandemic, classroom teaching at the business school was cancelled, and the remainder of the course syllabus was delivered through an OLE, on platforms such as Microsoft Teams. Interviews were conducted with the participants at the completion of the second semester in mid-April 2020. A total of 35 learners participated in the study. More than half of participants were male (57.14%) and 42.86% were female; 80% of the participants were between the ages of 21 and 24 years old and 20% were between the ages 25 and 30 years old. Participants used either a smartphone (65.71%) or a personal computer/laptop (34.28%) to attend classes online during the lockdown.

Structured interviews were conducted with 35 learners via Microsoft Teams. Participants were asked eight open-ended questions on the transition to OLE due to unforeseen circumstances and their perspectives on teaching and learning in a technology-mediated environment (Table1). The interview questions were validated by a panel of experts from the university: three faculty members and two students, who had been actively engaged in online learning in the previous 3 months. Two of the faculty members were experts in information technology and had been responsible for setting up the online learning platform at the institute. A pilot study was also conducted to assess the appropriateness of the interview questions with a sample of four learners. An iterative process was conducted to establish the reliability and face validity of the questions.

Table 1

Interview Questions Protocol

| Interview questions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interviews were transcribed and initial coding was conducted using NVivo software, which led to the identification of patterns, categories, and relationships among the codes. A total of 15 categories were identified in the interview data. The categories were further analyzed and five key themes emerged.

The increased risk of infection due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions imposed on the movement of individuals by the regulatory bodies across India impeded classroom teaching. In the interviews, participants shared their perceptions on the shift to an OLE at their university due to the pandemic and the benefits and challenges of online learning. Five themes emerged from the analysis of the participant interviews: accessibility and comfort, Internet connectivity, OLE effectiveness, course content, and interactions between learners and instructors.

Accessibility and comfort were a prominent theme in the participants’ responses to the interview questions. The word “accessibility” is defined as the quality of being able to easily reach and use (Kulkarni, 2019). The quality of comfort is twofold. It refers both to comfort or ease in using the technology and the comfort arising from the flexibility of place and time in accessing the online content. Online teaching helped learners easily reach their classes at any time and from anywhere. The participants preferred the OLE to traditional classroom learning as it provided them with easy access to the course content and the comfort of learning from home. Some of the participants’ responses are presented below.

Joining a session is just a matter of click. We could get connected to a session in the ease of being in our bedroom/study room. Planning a day becomes easy as it saves travel time/session organizing, accommodating time. (Participant 13, female)

As I know my session starts at 10, I connect to the meeting 5 minutes before. No, there were no issues with time management. It is so comfortable. (Participant 15, male)

The main advantage of online learning is that students can participate in classes from anywhere in the world provided they have a computer and an Internet connection. Besides, the online format allows physically challenged students and teachers more freedom to participate in class. Participants access the virtual classroom through their computers instead of having to go to class physically. (Participant 18, male)

Convenience is a major benefit of online education. (Participant 7, male)

The learners mentioned that prior to the transition to the OLE, they went to the university even for a single class, wasting a major part of their day in unproductive travel time. Online learning made attending classes convenient, saving learners both the time and energy. However, the positive impact of accessibility is, to a certain extent, mitigated by the fragile Internet connectivity in many parts of the country. For the classes to be truly comfortable and accessible, access to reliable Internet connectivity is required.

Participants emphasized the importance of having a computer and Internet connectivity to participate in the online classes. Having a desktop, tablet, smartphone, or laptop and access to the Internet with unhindered, seamless connectivity are required for learning in online environments. Most of the participants (n=32) stated that Internet connectivity was one of the biggest barriers to their online learning. Due to fluctuations in Internet connectivity across the geographical locations in which the participants resided, effective online learning was not always possible, resulting in reduced learner motivation; and, in some cases, learners were unable to attend classes, especially from remote locations, such Amravati, Jalgoan, Ratnagiri, and Raigarh. The learners pointed out that the technological limitations arising from poor network connectivity, and glitches in the audio/video functions due to low network speed, were a major cause for lack of motivation. Low Internet speeds resulted in loss of microphone and speaker functions, with negative impact on learner attention and motivation, rendering the teaching and learning process ineffective.

The biggest lack of motivation to attend lectures is from technological limitations due to the reliability of Internet connectivity. Poor network, glitches in the audio/video make it hard to link the topic and the voice of the lecturer, which causes the lecture to be ineffective and hard to understand. Too much noise in the background make it hard to concentrate in the lecture. Too much mail in the email inbox regarding the lecture schedules and invites. Everything gets piled up, and it makes it so hectic. Some students feel that online lectures consume a lot of Internet data, which they have to reserve for the rest of the day. (Participant 27, female)

[The OLE] is good but a little bit of distraction and technical issues due to network problems create hurdles between classes. (Participant 14, female)

We are on time to attend the session, but the Internet connection stability went the wrong way many times. (Participant 30, male)

Some students want to connect and learn but are not able to because they don’t have that much Internet access or have connectivity problems in their area. (Participant 29, male)

Being in a hometown, which is a small village, there’s always this problem of Internet connectivity. So here we need to find certain places where Internet connectivity is good enough to attend online sessions. Otherwise, as far as theoretical subjects are concerned, there are no major drawbacks as platforms like zoom are quite good enough for teaching activities. (Participant 34, female)

Online sessions are needed for the current situation during this lockdown. It will help students to complete their academic requirements and also enable the use of technology for the right purpose. This comes under strengths. While many students are from a rural background, Internet services, bad network connections, technical issues are some weaknesses of online sessions. (Participant 24, female)

As the research was conducted during the ongoing lockdown in India, the learners were sensitive toward the imposed restrictions on the movement of the instructors and considered OLEs the need of the hour. The shift to online learning enabled the completion of academic requirements, but the learning process was hindered by the lack of or poor Internet connectivity. A reliable Internet connection was seen as a basic requirement for uninterrupted sessions. The constant disturbances caused due to poor connectivity had negative impact on the effectiveness of the OLE.

The majority of participants (n=30) commented on the effectiveness of the OLE; however, their views were significantly divided. While some participants opined that online learning was more constructive than traditional learning and helped them concentrate better, some participants considered OLEs ineffective. Thus, this theme is divided into effective learning environment and ineffective learning environment.

Compared with traditional classroom learning, the OLE presented learners with unique benefits. Some participants mentioned that online learning afforded better focus on learning without the nuisance created by mischievous learners in traditional classroom environments or external disturbances.

Online teaching makes students’ misbehavior/disturbances and the audibility problems of classrooms into exceptions. (Participant 2, female)

Online teaching enables every student or member of the online meeting to listen to what the teacher or host is saying personally, hence everything that is taught is absorbed by the students to the fullest as there are no external disturbing factors to the concentration. (Participant 8, male)

Another participant added that the OLE improved the visibility and clarity of visual learning aids:

The presentation visuals, which used to be unclear to all the corners of the classroom/hall…are now visible and crystal clear due to the screen sharing feature of online teaching. The faculty’s teaching are disturbed less (apart from the technical issues), which enables them to teach smoothly. (Participant 3, male)

Some participants highlighted the shortcomings of the OLE, including Internet connectivity issues and lack of one-on-one discussions and clarification with the instructor. Some participants believed that the sessions turned into instructors’ one-way communication and that the teaching materials were not effectively presented. Another aspect that the participants pointed out was learners’ inability to concentrate in the sessions due to the many distractions they encountered and the instructors’ lack of control in the online environment.

Not every student can clear their doubts; there are disturbances in audio and in the network…. there’s no whiteboard where the topics are explained in a flowchart. Online there is just the screen and PowerPoint slides, and the main problem occurs when it comes to numerical topics. During lectures, our Wi-Fi or data is ON so there’s a lot of notifications, messages pop up, so there is a chance to get disturbed a lot. (Participant 17, female)

Few students can give 100 percent to online sessions, but there is a lack of seriousness about online sessions for many students because in-class teachers aware of students’ concentration but here in online sessions it is not possible to give attention to students; and distractions from study because of the current situation are possible because there may be negativity in students’ mind about their future career. (Participant 21, female)

Sometimes it’s difficult to concentrate as one is home. And the feeling of seeing face-to-face and virtual makes a big difference. The seriousness sometimes is lacking as there are distractions. (Participant 23, female)

The ambiance of the classroom is what I miss as that environment helps me personally to think more. (Participant 26, male)

While Participant 26 found the OLE effective in many ways, he preferred traditional classroom learning. The effectiveness and ineffectiveness of OLEs is also entangled with the kind of course that is being taught.

Even the participants who agreed that online learning is effective stated that numerical or practical classes were difficult to understand online. A general notion arising from the interviews highlights the suitability of online learning for theoretical courses and not for practical courses involving numerical concepts.

For a theoretical subject there are no problems; but for the numerical part, it is a bit difficult but still manageable. (Participant 1, male)

As for numerical, it is getting difficult to understand. (Participant 25, female)

Subjects like accounts, it is hard to understand in an online platform. Even for commerce students. (Participant 27, female)

It feels good to learn through online platforms, theoretical subject learning is good.... But, yes, numerical subjects can face some issues; it’s okay, our faculty are supporting us with everything possible: notes, a question bank, assignments, presentation, practice problems, etc. (Participant 29, male)

Participant 29 clarifies an important point regarding online teaching: Ultimately, ineffective classes can be made effective with constructive teacher-learner interactions.

It was a consensus among the learners that the physical absence of the faculty instructor mattered most to them. The participants felt the connection between the learner and the instructor was missing in the OLE. Due to the physical distance, learner participation was negatively impacted, leading to one-way communication of the instructor.

The online class is not participative as compared to face-to-face teaching. (Participative 23, female)

The classes online become very boring sometimes. It is not as interactive and lively as classroom teaching. (Participant 31, male)

I just doesn’t feel it’s a class. Most of the time all cameras are off, microphones are off; we hear only what the teacher says, or if one student answers. It seems we are listening to the radio. (Participant 32, male)

Furthermore, learner participation was hampered due to the challenges faculty instructors faced in seamlessly delivering sessions and courses using the online interface as well as difficulties the learners experienced themselves.

Many faculties find an issue with the interface of the applications used. There is not much effective control as it could be in a [physical] class. (Participant 19, male)

The online environment is very convenient but sometimes it creates a problem due to people not able to understand the user interface. (Participant 1, male)

The OLE caused barriers to participation, which led to a diminished experience of the connection between students and instructors. As participant 32 mentioned, the digital setup seemed to lead to a lack of interest among learners with negative impact on their connection with instructors.

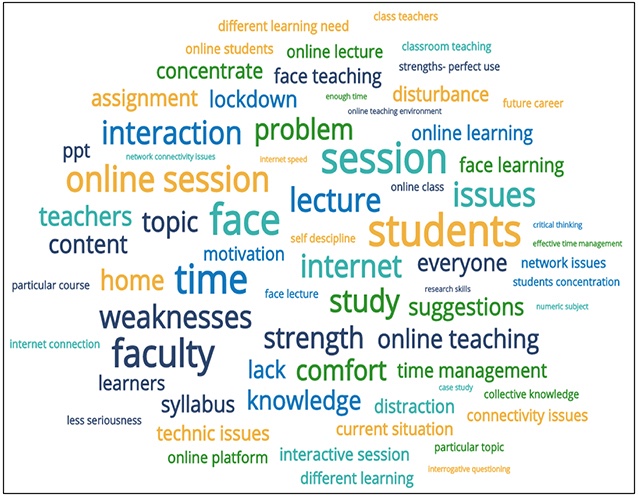

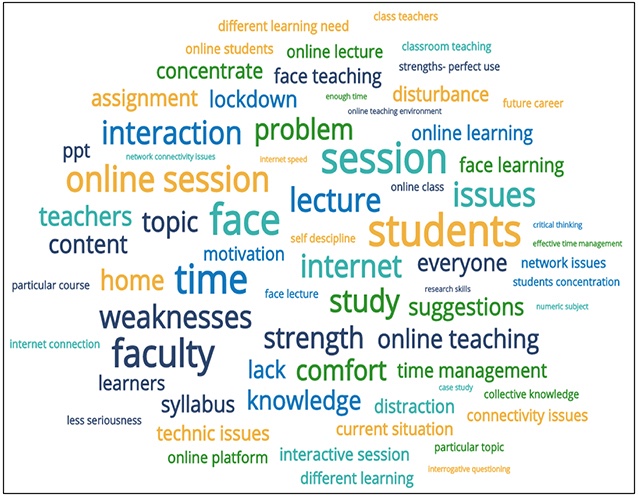

A word cloud formed using keywords from the participants’ interview responses are presented in Figure 1. The frequency of the participants’ use of the keywords is reflected in the size of the words in the figure. The larger the word, the more frequently it was used. The participants used words like faculty, face-to-face, session, and interaction quite often during the interviews. This shows an increased inclination towards the face-to-face interaction over the online mode of teaching. The importance of faculty members cannot be negated in the online learning environment either. Subsequently, online teaching, internet, comfort, content, and topic were the interviews' highlighted words. Closer inspection with participants' responses revealed that students were apprised about the pandemic situation and accepted the online mode of teaching. Nevertheless, the content and topic of discussion weighed in on online teaching and internet connectivity at their locations.

Figure 1

Word Cloud of the Keywords Participants Used Regarding OLEs

Note. The word cloud was created using free online tool available at: www.wordclouds.com.

The study focused on learners’ perceptions of the sudden shift from the traditional learning environment to an OLE, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perceived benefits and challenges of the OLE. Five themes emerged from the analysis: accessibility and comfort, Internet connectivity, effectiveness of the OLE, course content, and interactions between the learners and the instructors. The themes that emerged in this study are similar to the findings of earlier studies and, at the same time, are unique to the geographical context of the study: the city of Pune, the second-largest city in the state of Maharashtra, the commercial capital of India.

Accessibility and comfort facilitated the learners’ participation in online learning but also hindered it many times. The importance of accessibility and comfort in the OLE has been identified in earlier research as well (Hill, 2002; Hung et al., 2010; Kebritchi et al., 2017). Making technology accessible, and integration across the platform, is an important element in the success of online learning (Hooper & Rieber, 1995).

Internet connectivity and Internet access are considered an integral part of online learning, and the results of this study coincide with earlier studies in this area (Li & Irby, 2008; Luyt, 2013). Impaired Internet connectivity negatively impacted learners’ motivation, which, in turn, impacted their participation and success in the OLE.

Effectiveness of the OLE. Some of the participants were concerned about the effectiveness of the OLE in terms of their participation in and their ability to contribute to the class discussions. Deterrents to the online learning environment posed a threat to the participants learning due to lack of internet connectivity, the interaction between faculty instructor and participant, and absence of human contact between the instructor and learner. The findings supported the analysis by Gvaramadze (2012) as physical distance between the instructor and learner does not aid in developing the participants' core competencies in case of developing countries. The reduced response and participation between the faculty instructors and the learners complicate the situation, thus supporting the earlier work by Littefield (2018). Such factors hinder the learning process and thus proving detrimental to the effectiveness of OLE.

Course content also influenced participants’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the OLE. The study emphasizes the difficulty participants experienced in comprehending courses that involve numerical content and theorems, which concurs with the findings of previous studies (Ko & Rossen, 2017; Limperos et al., 2015).

Interaction between learners and instructors was impaired due to the OLE. The participants indicated the physical presence of a faculty instructor cannot be negated by the use of technology as it is central to their success or failure in a course. This result concurs with earlier studies on faculty instructors (Garrison et al.,1999; Richardson et al., 2016; Stone & Chapman, 2006). The feature of instructors’ physical presence has significant influence on learners’ participation in a course, a feature that loses ground in the OLE (Jorge, 2010; Tao, 2009). Similar to previous studies (Ali et al., 2018; McInnerney & Roberts, 2004; Szeto & Cheng, 2014), learners in this study expressed feelings of disconnect in the online classroom. Due to the increased interaction between the instructor and the technology, coupled with the interaction between learners and the technology, the participants were often frustrated, and thereby the effectiveness of the session was reduced.

Finally, the participants provided favorable responses regarding the transition to the OLE due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown in India, which forced instructors to switch to OLEs in a short time. Learners’ favorable views of the rapid transition to OLEs have been found in similar studies conducted in other geographical settings (Basilaia & Kvavadze, 2020; Chick et al., 2020; Reich et al., 2020).

This study offers several theoretical and practical implications. This is the first study to explore the transition to OLEs in a higher education institution, in the context of management/business education, in a developing country due to a pandemic or disaster. The sudden transition toward OLEs due to the COVID-19 pandemic has posed several challenges in developing countries, such as India, including lack of Internet connectivity, access to technological platforms by learners and instructors, familiarity with online teaching and learning approaches, and adoption of technology. From a theoretical perspective, this study provides insight into a specific geographical context and contributes to understanding the nature of online learning in different settings and its acceptance and adoption among learners and the instructors who are accustomed to teaching and learning in traditional classrooms. The study offers insight into the role of technology in the delivery of online learning modules and courses to learners in remote locations. Reliance on technology and lack of continuous Internet connectivity hinder the transition of learners toward online learning in developing countries, such as India.

In addition, the study has practical implications regarding infrastructure readiness for remote learners, acceptance and adoption of OLEs by faculty instructors, organizational support, and facilitating conditions. Remote learners spread across the country do not get seamless access to internet connectivity due to lack of infrastructure, thus posing limitations for the higher education institutions to reach out to the students in the online learning environment and hampering their learning. This leads to dissatisfaction among the learners and poses a threat to higher education institutions as seamless internet connectivity is outside their control. The acceptance of OLE by faculty instructors further diminishes the dissemination of knowledge among learners. The educational institutions need to support the seamless adoption of OLE by the faculty instructors and students alike. The higher education institutions can provide guidance and training to their faculty instructors to adopt OLE and educate the learners in turn. The study identified five themes in participants perceptions of the sudden transition toward an OLE: accessibility and comfort, Internet connectivity, OLE effectiveness, course content, and interactions between students and instructors. Participants’ responses may have been favorable because the transition toward the OLE was due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, despite the favorable responses, the study offers important conclusions related to the themes identified and the geographical context of the study. This qualitative study of the perceptions of learners toward OLEs in India provides a better understand the shortcomings and benefits of OLEs in developing countries. Quantitative studies on the acceptance of online learning in developing countries are warranted.

The study conclusions are based on research conducted within the geographical region of Pune city in India, and the study sample was limited to a small number of participants pursuing a master’s degree in business administration at Savitribai Phule Pune University. Further research should be conducted in other geographical areas in India with a larger sample. The implications of the study are also applicable to OLE implementation in post-pandemic scenarios in developing countries. Further research should be directed toward addressing the issues raised in this study (e.g., Internet connectivity, course content, and interaction between instructors and learners) to improve the delivery of OLEs in developing countries, such as India.

Agha, E. (2020, April 17). Online education a contingency measure during Covid-19 lockdown and not long-term strategy, say experts. News18. https://www.news18.com/news/india/online-education-a-contingency-measure-during-covid-19-lockdown-and-not-long-term-strategy-say-experts-2581297.html

Alexander, S., & Kwatra, N. (2020, April 6). In fight against coronavirus, India’s universities have lagged far behind China’s. Mint. https://www.livemint.com/education/news/in-fight-against-coronavirus-india-s-universities-have-lagged-far-behind-china-s-11586088831865.html

Ali, S., Uppal, M. A., & Gulliver, S. R. (2018). A conceptual framework highlighting e-learning implementation barriers. Information Technology & People, 31(1), 156-180. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2016-0246

Amirault, R. J. (2015). Technology transience and the challenges it poses to higher education. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 16(2).

Baker, S. C., Wentz, R. K., & Woods, M. M. (2009). Using virtual worlds in education: Second Life® as an educational tool. Teaching of Psychology, 36(1), 59-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280802529079

Barboni, L. (2019, December 12). From shifting earth to shifting paradigms: How Webex helped our university overcome an earthquake. CISCO, Upshotstories. https://upshotstories.com/stories/from-shifting-earth-to-shifting-paradigms-how-webex-helped-our-university-overcome-an-earthquake

Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

Benson, A. D. (2002). Using online learning to meet workforce demand: A case study of stakeholder influence. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 3(4), 443-452.

Boling, E. C., Hough, M., Krinsky, H., Saleem, H., & Stevens, M. (2012). Cutting the distance in distance education: perspectives on what promotes positive, online learning experiences. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(2), 118-126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.11.006

Carliner, S. (2004). An overview of online learning (2nd ed.). Human Resource Development Press.

Chakraborty, M., & Nafukho, F. M. (2014). Strengthening student engagement: What do students want in online courses? European Journal of Training and Development, 38(9), 782-802. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-11-2013-0123

Chen, S. J. (2014). Instructional design strategies for intensive online courses: An objectivist-constructivist blended approach. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(1). http://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/6.1.6.pdf

Chick, R. C., Clifton, G. T., Peace, K. M., Propper, B. W., Hale, D. F., Alseidi, A. A, & Vreeland, T. J. (2020). Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(4), 729-732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Conrad, D. (2002). Deep in the hearts of learners: Insights into the nature of online community. Journal of Distance Education, 17(1), 1-19. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/96579/

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

Duderstadt, J. J., Atkins, D. E., Van Houweling, D. E., & Van Houweling, D. (2002). Higher education in the digital age: Technology issues and strategies for American colleges and universities. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Garrison, D. R., Terry Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Gettleman, J., & Schultz, K. (2020, March 24). Modi orders 3-week total lockdown for all 1.3 billion Indians. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/world/asia/india-coronavirus-lockdown.html

Gvaramadze, I. (2012). Developing generic competences in online virtual education programmes at the University of Deusto. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 29(1), 4-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650741211192028

Harris, R. A., & Nikitenko, G. O. (2014). Comparing online with brick and mortar course learning outcomes: An analysis of quantitative methods curriculum in public administration. Teaching Public Administration, 32(1),95-107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0144739414523284

Hill, J. R. (2002). Overcoming obstacles and creating connections: Community building in Web-based learning environments. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 14(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02940951

Hofmann, D. W. (2002). Internet-based distance learning in higher education. Tech Directions, 62(1), 28-32. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/95322/

Hooper, S., & Rieber. L. P. (1995). Teaching with technology. In A. C. Orenstein (Ed.), Teaching: Theory into Practice (pp. 154-170). Allyn & Bacon.

Hung, M. L., Chou, C., Chen, C. H., & Own, Z. Y. (2010). Learner readiness for online learning: Scale development and student perceptions. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1080-1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.004

John, T., Gan, N., & Gupta, S. (2020, April 22). 90% of the world’s students are in lockdown. It’s going to hit poor kids much harder than rich ones. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/22/world/coronavirus-vulnerable-children-intl-gbr/index.html

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. (2019). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (7th ed.). Sage Publications.

Jorge, I. (2010, October). Social presence and cognitive presence in an online training program for teachers of Portuguese: Relation and methodological issues [Paper presentation]. The International Joint Conference and Media Days, Anadolu University, Eskisehir, Turkey. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8674

Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713

Keegan, D. (2013). Foundations of distance education (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315004822

King, F. B., Young, M. F., Drivere-Richmond, K., & and Schrader, P. G. (2001). Defining distance learning and distance education. AACE Journal, 9(1), 1-14. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/17786/

Ko, S., & Rossen, S. (2017). Teaching online: A practical guide (4th ed.). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203427354

Kulkarni, M. (2019). Digital accessibility: Challenges and opportunities. IIMB Management Review, 31(1), 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2018.05.009

Li, C. S., & Irby, B. (2008). An overview of online education: Attractiveness, benefits, challenges, concerns and recommendations. College Student Journal, 42(2), 449-458. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/103183/

Limperos, A. M., Buckner, M. M., Kaufmann, R., & Frisby, B. N. (2015). Online teaching and technological affordances: An experimental investigation into the impact of modality and clarity on perceived and actual learning. Computers & Education, 83, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.015

Littlefield, J. (2018, January 18.). The difference between synchronous and asynchronous distance learning. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/synchronous-distance-learning-asynchronous-distance-learning-1097959

Lowenthal, P. R., Wilson, B., & Parrish, P. (2009). Context matters: A description and typology of the online learning landscape. In M. Simonson (Ed.) Selected Papers on the Practice of Educational Communications and Technology Presented at the Annual Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (Vol. 2). Association for Educational Communications and Technology. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED511356.pdf

Luyt, I. (2013). Bridging spaces: Cross-cultural perspectives on promoting positive online learning experiences. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 42(1), 3-20. https://doi.org/10.2190/ET.42.1.b

McInnerney, J. M., & Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online learning: Social interaction and the creation of a sense of community. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 7(3), 73-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/jeductechsoci.7.3.73.pdf

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Moore, J. L., Camille Dickson-Deane, C., & and Krista Galyen, K. (2011). e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education, 14(2), 129-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.10.001

Moore, M. G. (1990). Contemporary issues in American distance education. Pergamon.

Nichols, M. (2003). A theory for e-learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 6(2), 1-10. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BbxRM8i-q-SPHGt8x7CBWo_fTKqniWyO/view

Oblinger, D., & Oblinger, J. L. (Eds.). (2005). Educating the next generation. EDUCAUSE. https://www.educause.edu/ir/library/PDF/pub7101.PDF

Press Information Bureau. (2020). Government of India issues orders prescribing lockdown for containment of COVID-19 epidemic in the country. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=200655

Reich, J., Buttimer, C. J., Fang, A., Hillaire, G., Hirsch, K., Larke, L. R., Littenberg-Tobias, J., Madoff Moussapour, R., Napier, A., & Thompson, M. (2020, April 2). Remote learning guidance from state education agencies during the Covid-19 pandemic: A first look. EdArXiv. https://doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/437e2

Richardson, J. C., Besser, E., Koehler, A., Lim, J. E., & Strait, M. (2016). Instructors’ perceptions of instructor presence in online learning environments. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4), 82-104. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i4.2330

Robinson, C. C., & Hullinger, H. (2008). New Benchmarks in higher education: Student engagement in online learning. Journal of Education for Business, 84(2), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.84.2.101-109

Romei, V. (2020, April 24). Global trade contracts as Coronavirus hits world economy. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/db3427f5-5394-4661-8e52-6447fd3d9ae9.

Saadé, R. G., He, X., & Kira, D. (2007). Exploring dimensions to online learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(4), 1721-1739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.10.002

Sharma, A. K. (2020, April 15). COVID-19: Creating a paradigm shift in India’s education system. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/covid-19-creating-a-paradigm-shift-in-indias-education-system/.

Stone, S. J., & Chapman, D. D. (2006). Instructor presence in the online classroom. ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED492845.pdf

Sun, A., & Chen, X. (2016). Online education and its effective practice: A research review. Journal of Information Technology Education, 15, 157-190. https://doi.org/10.28945/3502

Szeto, E., & Cheng, A. Y. N. (2014). Towards a framework of interactions in a blended synchronous learning environment: What effects are there on students’ social presence experience? Interactive Learning Environments, 24(3), 487-503. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.881391

Tao, Y. (2009). The relationship between motivation and online social presence in an online class [Doctoral dissertation, University of Western Florida]. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=4871&context=etd

Tavangarian, D., Leypold, M. E., Nölting, K., Röser, M., & Voigt, D. (2004). Is e-learning the solution for individual learning? Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 2(2), 265-272. http://www.ejel.org/volume2/issue2

Triacca, L., Bolchini, D., Botturi, L., & Inversini, A. (2004, June 21-26). Mile: Systematic usability evaluation for e-learning Web applications [Paper presentation]. ED-MEDIA 2004, World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications. Lugano, Switzerland. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/11709/

Walker, A. (2020, April 23). Developing world economies hit hard by Coronavirus. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52352395

Zapalska, A., & Brozik, D. (2006). Learning styles and online education. The International Campus-Wide Information Systems, 23(5), 325-335. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650740610714080

Learners' Perception of the Transition to Instructor-Led Online Learning Environments: Facilitators and Barriers During the COVID-19 Pandemic by Dr. Aakash Kamble, Dr. Ritika Gauba, Ms. Supriya Desai, and Dr. Devidas Golhar is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.