Volume 22, Number 2

Rhiannon Pollard and Swapna Kumar, EdD

University of Florida

The proliferation of online graduate programs, and more recently, higher education institutions’ moves to online interactions due to the COVID-19 crisis, have led to graduate student mentoring increasingly occurring online. Challenges, strategies, and outcomes associated with online mentoring of graduate students are of primary importance for the individuals within a mentoring dyad and for universities offering online or blended graduate education. The nature of mentoring interactions within an online format presents unique challenges and thus requires strategies specifically adapted to such interactions. There is a need to examine how mentoring relationships have been, and can best be, conducted when little to no face-to-face interaction occurs. This paper undertook a literature review of empirical studies from the last two decades on online master’s and doctoral student mentoring. The main themes were challenges, strategies and best practices, and factors that influence the online mentoring relationship. The findings emphasized the importance of fostering interpersonal aspects of the mentoring relationship, ensuring clarity of expectations and communications as well as competence with technologies, providing access to peer mentor groups or cohorts, and institutional support for online faculty mentors. Within these online mentoring relationships, the faculty member becomes the link to an otherwise absent yet critical experience of academia for the online student, making it imperative to create and foster an effective relationship based on identified strategies and best practices for online mentoring.

Keywords: e-mentoring, online mentoring, virtual mentoring, graduate mentoring

The relationship between students and faculty mentors has been established as one of the most important factors in determining the success and quality of graduate education as well as student retention (Khan & Gogos, 2013; Kumar et al., 2013; Lechuga, 2011). The ubiquity of ICT (information and communications technology), the proliferation of online graduate programs, and more recently, higher education institutions’ move to online interactions due to the COVID-19 crisis have led to mentoring increasingly occurring online. Although mentoring conducted in an online format aspires to similar goals as traditional mentoring, it needs to adapt to the online environment (Erichsen et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2013). In this context, it is important to examine how dyadic mentoring relationships between a graduate student and their faculty mentor (research supervisor) have been, and can best be, conducted when little to no face-to-face interaction occurs. What strategies or best practices have been identified in the literature to effectively mentor graduate students online?

Graduate education includes a wide spectrum when it comes to the clarity of expectations and programs of study, the experience of setbacks, and the growth of the student into individualized study, depending on the discipline and level (master’s or doctoral). The crux of this process is often the one-on-one dialogue between a student and their advisor or mentor (Berg, 2016; Deshpande, 2017; Sussex, 2008). This process can become more difficult in an online context, in which enrolled students might be non-traditional and culturally diverse, and faculty members might lack experience mentoring students in the online environment (Deshpande, 2017; Kumar & Johnson, 2017). Issues, strategies, and outcomes surrounding the online mentoring of graduate students are of primary importance for the individuals within a mentoring dyad and for universities offering online or blended graduate education; during the COVID-19 pandemic, this applies to almost all universities in the US. For online students, the faculty advisor may represent the entirety of their university experience (Deshpande, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015), which places significant pressures on the mentoring relationship in this context. During this pandemic, traditional, on-campus graduate students are confronted with campus closures and the inability to meet with their mentors face-to-face (Pardo et al., 2020), and as such, these pressures typical to online mentoring relationships are being felt more widely.

Research on online mentoring in graduate education, specifically on the challenges, effectiveness, practices, and outcomes of online mentoring of graduate students, is scarce (Bender et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2019). Skepticism exists regarding the ability of online programs or faculty members to provide sufficient mentoring in online settings, especially within doctoral programs (Columbaro, 2009). Given the recent increased need for mentoring graduate students online—even within on-campus and blended graduate programs due to COVID-19—there is an urgent need for research into the practices and outcomes of online graduate mentoring relationships.

This review of literature was guided by the following questions:

For the purposes of this inquiry, the following terms were searched in various combinations to ensure maximum possible results within the published literature: online, graduate student, virtual, distance, e-learning, Web-based, e-mentoring, supervision, telementoring, cybermentoring, advising, supervising, mentoring, doctoral, PhD, and master’s. Databases searched included ERIC, Google Scholar, and a combined search tool from a US university library that accessed EBSCO, DOAJ, JSTOR, and SpringerLink. The results were restricted to peer-reviewed online and print journals published between 1999 and 2019.

The literature found by this search was then perused based on three criteria. Any articles that did not pertain specifically to graduate education (master’s and doctoral) were excluded. Second, we included only peer-reviewed journal articles that directly addressed the one-to-one mentoring of graduate students at a distance or online, and by faculty members in higher education institutions. The focus was on faculty (mentor) to graduate student (mentee) dyads in which academic and research supervision occurred, regardless of the presence of supplemental group or peer mentoring. Third, we included only empirical research. Studies that did not include the explicit investigation of mentoring dyads were excluded. This resulted in 24 articles from 20 journals worldwide. We then included literature reviews that focused on graduate mentoring at a distance (Byrnes et al., 2019; Columbaro, 2009; Deshpande, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015), leading to a total of 28 articles from 22 journals worldwide (Table 1). These four literature reviews focused solely on online doctoral student mentoring whereas our broader literature review examined both master’s and doctoral student mentoring online across disciplines. Seminal articles about e-mentoring or mentoring at a distance across contexts were used for background information and for discussing the identified strategies or challenges in the included studies but were not included in the research findings presented in this article.

Table 1

Empirical Articles Included by Journal

| Journal | Citation |

| Adult Learning | Columbaro, 2009 |

| American Journal of Distance Education | Berg, 2016; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Stein & Glazer, 2003 |

| American Journal of Qualitative Research | Duffy et al., 2018 |

| Group & Organization Management | de Janasz & Godshalk, 2013 |

| Higher Education for the Future | Deshpande, 2017 |

| Innovations in Education and Technology | De Beer & Mason, 2009 |

| International Education Studies | Deshpande, 2016 |

| International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education | Kumar et al., 2013 |

| International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship | Welch, 2017 |

| Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision | Bender et al., 2018 |

| Journal of Educational Research and Practice | Jameson & Torres, 2019 |

| Journal of Professional Nursing | Broome et al., 2011 |

| Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning | Crawford et al., 2014; Kumar & Johnson, 2017 |

| Occupational Therapy in Health Care | Jacobs et al., 2015 |

| Occupational Therapy International | Doyle et al., 2016 |

| Online Learning Journal | Byrnes et al., 2019; Rademaker et al., 2016 |

| Quality Assurance in Education | Andrew, 2012 |

| Studies in Higher Education | Erichsen et al., 2014; Kumar & Johnson, 2019; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015 |

| The Journal of Continuing Higher Education | Roumell & Bolliger, 2017 |

| The Journal of the National Academic Advising Association | Schroeder & Terras, 2015 |

| Teaching in Higher Education | Ross & Sheail, 2017 |

| Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education | Suciati, 2011 |

The terms online, virtual, and distance, as well as e-mentoring, advising, and mentoring, have been used interchangeably in the literature to describe students and faculty who are in disparate geographic locations for the majority of their time in a mentoring relationship. In this paper, we used the term online mentoring to encompass the various roles played by faculty with respect to the academic, professional, psychosocial, and cognitive development of students (Kumar & Johnson, 2019).

Each article was read once in its entirety without conducting analysis. During the second read, findings within the article relevant to the research questions were collected in a spreadsheet and given an initial code to generate categories such as: (a) benefits, (b) challenges, (c) strategies, (d) methodological approaches, (e) faculty perceptions, (f) student perceptions, and (g) technologies. When all articles were read and coded, these categories were synthesized to form the following themes that are described in detail below: (a) general details of articles and research approaches; (b) positive aspects of online mentoring; (c) challenges to mentoring online; (d) strategies and best practices for mentoring online graduate students; and (e) factors influencing the online mentoring relationship. The spreadsheet of codes, themes, and citations was shared between co-authors to ensure integrity and consistency as well as accuracy.

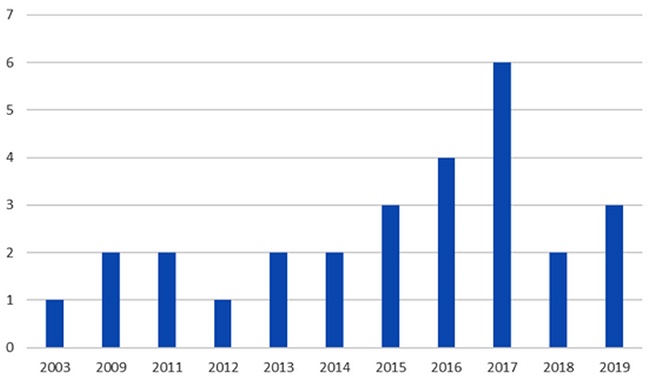

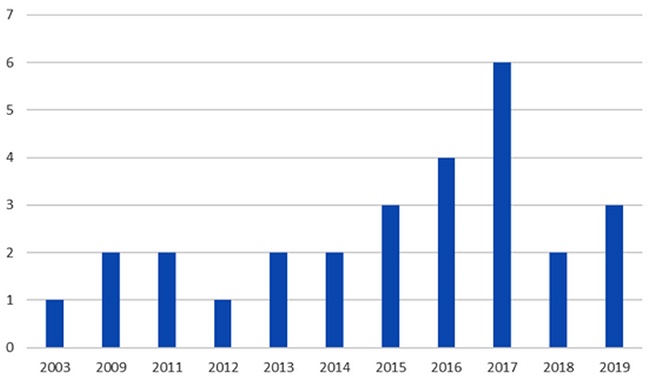

The 28 articles found were published between 2003 and 2019, with the largest number of articles published in 2017 (Figure 1). Twenty of the articles focused on doctoral education, three on master’s programs, and five included participants across master’s and doctoral programs. Twenty of the studies were conducted in completely online programs, four in blended programs, two in both online and blended programs, and two included participants from online, blended, and on-campus programs. Twenty-two of the programs studied were in the United States, three in the United Kingdom, and one each in Australia, South Africa, and Indonesia.

Figure 1

Number of Articles Published Per Year

Various research methods were used in the empirical studies. Twelve of the 28 were purely qualitative studies; nine of these studies included interviews, one was a collaborative autoethnography, and another a case study. Of the remaining 16, seven articles were quantitative and used surveys, five articles were mixed-method studies that used both surveys and interviews, and four were literature reviews.

Researchers made use of a variety of approaches to explore the relationship between mentor and mentee online, including the focus of the investigation (e.g., on the relationship, the methods of interaction, the perceptions of mentors and mentees), the theoretical and/or conceptual foundations, and the method of study. The literature spanned almost two decades, and therefore included many technologies, such as learning management systems, text messaging, telephone calls, social networking, videoconferencing, and more. However, researchers tended to focus on the process rather than technologies. This appeared to reinforce de Janasz and Godshalk’s (2013) conclusion that comfort with computer-mediated communication may no longer be a relevant construct in considering satisfaction with the mentor-mentee relationship online due to the extensive use of ICT. Articles often mentioned the technologies involved and how they were used within online mentoring relationships, but the emphasis was on why and how online mentoring was occurring in graduate programs, rather than analyses of which technologies were used and how well they performed.

Online mentoring serves the same functions as traditional mentoring and can be just as effective, providing similar benefits (de Janasz & Godshalk, 2013; Welch, 2017; see Table 2). Students in multiple studies have reported high satisfaction with online mentoring and their positive experience with peer groups (Broome et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2015). Online mentoring can be used to guide graduate students in areas of professional development as well as in their research (Doyle et al., 2016). Logistically, one advantage of online mentoring over traditional mentoring is the ability to overcome obstacles of distance and time. The affordances of convenience and flexibility granted by online interactions (An & Lipscomb, 2013; Schichtel, 2010) can also serve to enhance student diversity and access to education. The nature of the online environment in which mentoring takes place also creates a written record of interactions which can be referenced for reflection, clarification, or even research (de Beer & Mason, 2009; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Sussex, 2008). Though online graduate students preferred synchronous interaction (Andrew, 2012; Kumar et al., 2013; Kumar & Coe, 2017), they nonetheless reported an appreciation for the opportunity to reflect using asynchronous technologies.

Lechuga (2011) found that online mentoring relationships may mitigate perceptions of status differences between mentor and mentee, thus allowing lower status individuals more freedom to express themselves within the relationship (An & Lipscomb, 2013; Griffiths & Miller, 2005). In fact, Griffiths and Miller (2005) extended the definition of e-mentoring laid out by Bierema and Merriam (2002) with the qualification that it was precisely the boundarylessness and egalitarian nature of e-mentoring that distinguished it from traditional mentoring; the ability to have an interaction with a more experienced, supportive role model in the absence of social status pressures and influences may be a key factor regarding the beneficial possibilities of online technologies to mediate mentoring.

Mentoring online benefits faculty by providing them with opportunities for professional growth and refinement of mentoring skills, opportunities to learn from students’ ideas, and can lead to a renewed commitment to their fields of expertise (Broome et al., 2011; Doyle et al., 2016; Lechuga, 2011).

Table 2

Positive Aspects of Online Mentoring

| Positive aspect | Perspective | Citation |

| High levels of satisfaction with program | Students | Broome et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2015 |

| Positive impacts to students’ professional development | Students Faculty | Doyle et al., 2016; Jacobs et al., 2015 Doyle et al., 2016 |

| Ability to use multiple means of communication | Students | Kumar & Coe, 2017 |

| Peer groups (community) enhancing experience | Students | Broome et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Ross & Sheail, 2017 |

| Positive impacts to faculty professional development | Faculty | Broome et al., 2011; Doyle et al., 2016; Lechuga, 2011 |

| Convenience and flexibility | Students | Andrew, 2012; Ross & Sheail, 2017 |

| Records of correspondence | Students Faculty | Andrew, 2012; Kumar et al., 2013 de Beer & Mason, 2009; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015 |

| Scalability of mentoring | Faculty | de Janasz & Godshalk, 2013 |

A commonly-stated challenge when mentoring students online is the potential for miscommunication and reduction of information exchanged during online interactions due to lack of social presence, the loss of non-verbal cues, and the one-way-at-a-time nature of asynchronous communication (Duffy et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2017, 2019; Lechuga, 2011; Ross & Sheail, 2017). Faculty mentors and their graduate students may feel anxious about the online relationship and less connected as a result of the absence of social presence within textual communication, and this may impede their ability to form a strong mentoring dyad (Sussex, 2008).

Additional challenges of online mentoring for students involve (a) cultural differences, (b) technical difficulties, (c) time management, (d) difficulty writing and receiving written feedback, and (e) life events interrupting study (Table 3). Despite their commitment to supporting their online graduate students, a lack of institutional incentives for faculty time spent advising can impact how much mentoring they are willing or able to give to mentees (Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Sussex, 2008). In addition, faculty reported feeling limited in the ways in which they could mentor online graduate students (Roumell & Bolliger, 2017), which might be an indication of professional development or other instructional support needed at the institutional level.

Table 3

Challenges of Online Mentoring

| Challenge | Perspective | Citation |

| Anxiety about online relationship | Students | Bender et al., 2018; Ross & Sheail, 2017 |

| Difficulty with technology | Students | Bender et al., 2018; Welch, 2017 |

| Need for more communication | Students | Andrew, 2012; Broome et al., 2011; Ross & Sheail, 2017; Schroeder & Terras, 2015 |

| Lack of connection with faculty/students | Students | Andrew, 2012; Deshpande, 2016; Erichsen et al., 2014; Ross & Sheail, 2017; Sussex, 2008 |

| Cultural difference—impact on communication | Students | Berg, 2016; Deshpande, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Sussex, 2008 |

| Limitations of online communication | Faculty | Duffy et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2017, 2019; Lechuga, 2011 |

| Time commitments and increased workload | Faculty | Duffy et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2019; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Sussex, 2008 |

| Learning time management | Students | Kumar & Coe, 2017; Welch, 2017 |

| Difficulty with writing | Students | Broome et al., 2011; Kumar & Johnson, 2017, 2019 |

| Understanding written feedback | Students | Erichsen et al., 2014; Kumar & Johnson, 2017 |

| Life events interrupting study | Students Faculty | Kumar & Johnson, 2017 Duffy et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2019 |

| Difficult to research in professional practice | Students Faculty | Ross & Sheail, 2017 Kumar & Johnson, 2017 |

| Unfamiliarity with best practices | Faculty | Deshpande, 2016, 2017; Duffy et al., 2018; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Kumar & Johnson, 2017 |

The role of the faculty mentor is to provide educational, professional, and personal support for their graduate students, whether online or in-person (Columbaro, 2009; Doyle et al., 2016; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Welch, 2017). Important strategies for effective online mentoring in the literature (Table 4) revolved around fostering interpersonal aspects of the relationship, such as trust, connection, respect, and confidence, through online communication (Bender et al., 2018; Deshpande, 2016). Common behaviors of good mentors included treating mentees as individuals, taking the mentoring process seriously, and maintaining high availability for mentee needs (Crawford et al., 2014; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Schroeder & Terras, 2015). Faculty in the research described the development of trust through feedback, consistency (which includes providing structure), and personal connection (Rademaker et al., 2016). One strategy that seemed to strongly influence student perceptions of satisfaction with the online mentoring relationship was that mentors should be responsive, and express concern and care for the well-being of the student as an individual (Crawford et al., 2014; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Ross & Sheail, 2017; Stein & Glazer, 2003; Welch, 2017). Further, mentors should maintain cultural sensitivity during communications with mentees who may experience communication and social norms differently than do their mentors (Berg, 2016; Deshpande, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Sussex, 2008).

Frequent communication has been identified as critical to the online mentoring relationship (Broome et al., 2011; de Janasz & Godshalk, 2013; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Coe, 2017) as it helps to foster immediacy and reduces temporal distance that can create difficulties in the relationship (Duffy et al, 2018; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015). The emphasis on communication in the literature, coupled with students’ need for timely, clear, and constructive feedback as well as encouragement, indicated that online mentors should have technical, communication, social, and cognitive competencies (Byrnes et al, 2019; Erichsen et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2013; Schichtel, 2010). Both faculty mentors and student mentees emphasized the need for an awareness of netiquette—communicating politely and with care online—as asynchronous communication opens the potential for miscommunication due to the absence of body language, vocal intonation, and facial expression. Videoconferencing was effectively used by mentors in the literature to overcome this challenge (Kumar & Johnson, 2019). Sussex (2008) also recommended the use of recorded audio for students as a personal method of providing feedback.

Student needs and expectations relative to online mentoring may not be well understood or may be presumed rather than explicitly explored (Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Schroeder & Terras, 2015; Stein & Glazer, 2003), and the context of the interaction itself can lead to different expectations on the part of student mentees and faculty mentors (Lechuga, 2011). Because of this, providing a structure for online mentoring and negotiating explicit expectations and agreements at the outset of the mentoring relationship has been seen as an important strategy (Andrew, 2012; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2013; Kumar & Johnson, 2017, 2019; Suciati, 2011). Maintaining consistency of mentoring interactions, as well as frequency, was also important (Byrnes et al., 2019; Rademaker et al., 2016). Establishing predictable virtual office hours was suggested as one way of accomplishing this (Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015), as was scheduling regular meetings or updates (Kumar et al., 2013; Kumar & Johnson, 2019). Barnes and Austin (2009) suggested that mentoring structures and agreements may be best addressed by institution-level clarification of roles and expectations for mentoring graduate students with, and without, online technology. In spite of the emphasis in the literature on the significance of providing structure, students in different stages of development were also reported to need different emphasis in their mentoring relationships (Jameson & Torres, 2019). Such flexibility in terms of modality, frequency, and/or type of interaction was another important strategy for supporting online mentees (Byrnes et al., 2019; Doyle et al., 2016; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Sussex, 2008). Notwithstanding the existence of agreed-upon structures and processes, flexibility of faculty mentors to support students as needed was seen as essential in the online environment to reduce student anxiety and isolation.

Because online students are separated from the social and structural support networks typically found in a university campus environment, such structures or networks should be created in the online environment. Many studies indicated online graduate student preference for, and emphasis on, peer mentoring groups, and that a sense of community positively influenced the experience of being an online graduate student (Broome et al., 2011; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Ross & Sheail, 2017; Welch, 2017). Such community has been fostered by the implementation of one-time or periodic group experiences, communities of practice, or the use of cohorts for online graduate students (Andrew, 2012; Deshpande, 2016; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015).

Participants in some studies expressed frustration with technology and the amount of time spent working through technical problems (Bender et al., 2018; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Welch, 2017). Because individual needs and technical access may vary widely across time and students, a flexible and engaging variety of technical options for communication and the provision of feedback were essential (Doyle et al., 2016; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Welch 2017). Participants in the research we reviewed recommended using live Webcam interaction when possible, as a close approximation to face-to-face interaction and a way to foster connection (Bender et al. 2018; Doyle et al., 2016; Kumar & Johnson, 2019; Sussex, 2008). Student participants indicated that their own anxiety related to technology concerns was alleviated when their mentors displayed confidence and competence in managing the communication methods. In this context, online orientations to technology can be helpful for both faculty and students (Andrew, 2012; Bender et al., 2018).

Workloads were a common challenge for faculty mentoring online (Kumar & Johnson, 2019; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Sussex 2008). While institutional support was important for student success, it was just as important for faculty members engaging in online mentoring (Kumar & Coe, 2017; Kumar & Johnson, 2019). Strategies to incentivize participation, to minimize unnecessary temporal costs, to acknowledge mentoring workload, and to support the online mentoring experience have been employed by departmental or institutional administration. Additionally, the provision of templates or procedural frameworks (agreements, evaluations, and other milestone documents) as well as a repository of online resources for online mentoring helped faculty mentors (Doyle et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2018).

Institutions have supported faculty who are mentoring online graduate students by offering professional development to assist them with learning how to mentor students online, how to create effective interactions and/or environments, and also to help them acquire the technical, communication, social, and managerial skills important in the online environment (Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Schichtel, 2010). Deliberate pairing of more-experienced mentors with less-experienced faculty has been helpful as well (Deshpande, 2016, 2017; Kumar & Johnson, 2017). Participation in peer groups, peer networks, and mentoring communities has been beneficial for faculty who have not previously experienced online learning environments; as with online students, they may experience isolation (Duffy et al., 2018).

Table 4

Strategies for Graduate Mentoring Online

| Strategy | Citation |

| Supporting mentees | |

| Fostering interpersonal aspects, especially trust and care for individuals | Bender, et al., 2018; Crawford et al., 2014; Deshpande, 2016; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Rademaker et al., 2016; Ross & Sheail, 2017; Stein & Glazer, 2003; Welch, 2017 |

| Availability of mentor | Crawford et al., 2014; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Schroeder & Terras, 2015 |

| Cultural sensitivity | Berg, 2016; Deshpande, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Sussex, 2008 |

| Frequent, timely, and clear communication/feedback | Broome et al., 2011; Byrnes et al, 2019; de Janasz & Godshalk, 2013; Erichsen et al., 2014; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Kumar et al., 2013; Schichtel, 2010 |

| Providing structure and setting expectations | Andrew, 2012; Byrnes et al., 2019; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2013; Kumar & Johnson, 2017, 2019; Lechuga, 2011; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Rademaker et al., 2016; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Schroeder & Terras, 2015; Stein & Glazer, 2003; Suciati, 2011 |

| Flexibility to address individual needs | Byrnes et al., 2019; Doyle et al., 2016; Jacobs et al., 2015; Jameson & Torres, 2019; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Sussex, 2008; Welch 2017 |

| Creation of cohorts or communities | Andrew, 2012; Broome et al., 2011; Deshpande, 2016; Jacobs et al., 2015; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Ross & Sheail, 2017; Welch, 2017 |

| Use of videoconferencing for interaction | Bender et al 2018; Doyle et al., 2016; Kumar & Johnson, 2019; Sussex, 2008 |

| Technological competence | Andrew, 2012; Bender et al., 2018; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Welch, 2017 |

| Supporting mentors | |

| Incentives for increased workload | Kumar & Coe, 2017; Kumar & Johnson, 2019; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Sussex 2008 |

| Professional development | Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017; Schichtel, 2010 |

| Mentoring communities | Deshpande, 2016, 2017; Duffy et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2017 |

| Standardized templates and resources | Doyle et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2018 |

Differences in motivation, participation, values, and personal characteristics influence the effectiveness of mentoring relationships (Sussex, 2008). Researchers have asserted that the online mentoring relationship should include psychosocial and interpersonal as well as intellectual aspects (Berg, 2016; Doyle et al., 2016; Jameson & Torres, 2019; Kumar & Johnson, 2017; 2019).

Mentors in the research expressed a belief that their most important role was to build trust and a relationship with the student because this contributed to the success of the relationship (Rademaker et al., 2016; Roumell & Bolliger, 2017). These conclusions were supported by Erichsen et al.’s (2014) research where trust and personal connection were the factors described by students as the most positive aspects of the mentoring relationship.

de Janasz and Godshalk (2013) found that during online mentoring, similarities in values could quickly facilitate trust between mentor and mentee. They also found that the perceived similarity of values, not demographics, had an effect on the mentoring relationship. If value similarities lead to more trust and more trust leads to higher satisfaction, it follows that mentoring pairs should be intentionally matched whenever possible (Berg, 2016). The same authors suggested that it was not only personalities and values but also knowledge and skill matching that were important to effective mentoring. In contrast, Doyle et al. (2016) found that mentors felt the level of similarity they shared with their mentees was not important.

Along with trust, faculty members’ demonstrated empathy towards students was perceived to influence the online mentoring relationship (Duffy et al., 2018). In addition to complicating factors such as financial difficulties, personal commitments, or changes that might be common to all types of programs, students in online graduate programs often work full-time. Some might also conduct their graduate projects or research in professional contexts. Faculty members’ adaptability to and support of online students’ navigation of multiple commitments influenced the mentor-mentee relationship online (Jameson & Torres, 2019; Kumar & Coe, 2017).

Student satisfaction with the online mentoring relationship across contexts was positively affected by the perception of the mentor as a present and supportive confidant or ally (de Janasz & Godshalk, 2013; Kumar & Coe, 2017; Lechuga, 2011). Several studies (Deshpande, 2017; Nasiri & Mafakheri, 2015) corroborated the notion that “in a distance environment, the mentor becomes the connector to resources, to institutional culture, to scholarly values, to other learners, and to the content of learning” (Stein & Glazer, 2003, p. 21). Online doctoral students suggested that it was their own responsibility to continue the momentum of the mentoring relationship by engaging frequently with their mentor (Kumar et al., 2013).

From a faculty perspective, while the focus and nature of online mentoring was dependent on the type of university and program, mentors’ satisfaction with online mentoring was influenced by their workload (i.e., the number of students that they mentored at a time, as well as their access to institutional resources that supported online mentoring; Duffy et al., 2018; Kumar & Johnson, 2019).

Kumar and Johnson (2017) found that mentors’ experiences as doctoral student mentees influenced their approaches to mentoring online. Roumell and Bolliger (2017) found that mentors of online doctoral students expected them to have generally the same attitudes, engagement, and drive as face-to-face students, despite acknowledging the difficulties in establishing the relationships that foster these qualities (Sussex, 2008).

This literature review focused only on peer-reviewed journal articles and did not include dissertations, book chapters, or other literature (e.g., conference proceedings). Additionally, only empirical research that focused on online graduate mentoring in higher education was included. The literature search spanned two decades (1999-2019), and the articles reviewed were published between 2003 and 2019, during which time information and communications technologies have rapidly evolved. Although the studies reviewed focused on processes and strategies rather than technology, it is important to acknowledge that availability of technologies, and the affordances they provide to students and faculty, can influence mentoring process, strategy, or both. Although bandwidth and access to technologies might have differed even within the United States (where most of the studies took place), insight into mentoring practices in other countries, regions, and cultures can enhance the literature on online mentoring, especially as online education increases opportunities for students globally.

Online mentoring is “qualitatively different than land-based mentoring” (Bierema & Merriam, 2002, p. 214), and though it shares many similarities in goals and even structures, mentoring online has generated a new kind of mentoring relationship requiring contextual negotiations and specialized strategies (Kumar & Johnson, 2017; Stein & Glazer, 2003). The studies reviewed in this paper were conducted in a variety of contexts—online for-profit universities, universities (some of which were research intensive) with online programs or blended programs, and on-campus programs with online mentoring components. Common challenges, factors, and strategies that were identified notwithstanding, the types of support required by students and faculty engaged in online mentoring relationships should be expected to differ based on the program in which they teach and learn, and based on the focus of the relationship itself (e.g., projects, research, career development).

Though there is as yet no concrete model for how to mentor graduate students online, the literature reviewed revealed several factors that influence these mentoring relationships and provided strategies that were found to be valuable to participants. Graduate students in online mentoring relationships need frequent and timely communication and feedback, structure and clear expectations for themselves and their faculty mentors, and they need to feel their mentors are personally engaged with them as individuals. Faculty mentors’ presence, as discussed by Anderson et al., 2001, and their ability to connect, develop trust, and communicate with students have all been acknowledged as essential in online courses. In addition, these attributes appear to be even more crucial in graduate mentoring relationships, whether they occur at the master’s or doctoral level, within formal courses, internships, projects, or during dissertation supervision processes. Faculty mentors can be primarily supported by institutional efforts to improve their comfort and skill with online mentoring and to incentivize or reduce the workload increases they may experience when serving as online graduate student mentors, especially in cohort-based programs.

The nature of mentoring activity, and its meanings and effects, changes when it takes place online. Online technologies afford flexibility in more ways than time, space, and convenience; they provide means to communicate differently, both more multi-faceted and more immediately at the same time, using images, sharing links or files, emoji, reactions, and always, textual commentary. The lack of non-verbal social status and demographic cues are reported to foster a more equitable relationship between mentor and mentee. At the same time, technology has also been reported to interfere with the development of personal connections, which are more natural to establish when a faculty mentor and student mentee meet in person. On-campus environments that adopt or incorporate online mentoring processes or online programs with on-campus meetings might benefit the most; in those cases, mentors and students may have formed relationships in person and can continue the process in an online environment.

An important challenge in the current COVID-19 crisis relates to transitioning and supporting traditional, on-campus graduate student mentees as they find themselves operating in a fully online format. Faculty must “reimagin[e] how to do mentoring” (Ghani, 2020, p. S37) even as faculty and graduate students alike may be experiencing significant challenges and distress due to personal, emotional, economic, or health-related issues in addition to the educational and professional challenges of learning to interact in new ways, using new technologies. Although the theme of life events interrupting study (see Table 3) was extant within the literature published prior to 2020, it is likely to hold greater relevance in the near-term future, as large numbers of currently-enrolled graduate students are undoubtedly experiencing interruption in the status quo of their lives. While the research on academic and professional impacts of the pandemic is still emerging, it seems reasonable to suggest that faculty engaging in online mentoring should emphasize the supportive and nurturing aspects of the relationship during this period of potentially unprecedented stress on graduate education and on the mental health of these students (Ghani, 2020; Pardo et al., 2020), as well as tending to their own stress and mental well-being.

The goal of this literature review was to identify challenges faced and strategies used by online mentors and mentees, as well as factors that influence online mentoring in graduate education in empirical research published in the last two decades, a period in which online master’s and doctoral programs have proliferated in higher education. The number of publications on this topic were found to have increased since 2016, probably indicating the increased need for, and prevalence of, graduate student mentoring online. Empirical literature on online mentoring in graduate education mainly focused on doctoral dissertations at a distance, highlighting the unique nature of online doctoral mentoring and challenges faced in the online environment. Given the increasing number of master’s projects, practica, internships, and theses also being mentored online, there is a need to investigate strategies, challenges, and factors related to the online mentoring of master’s students as well.

Although some studies addressed the effectiveness and outcomes of online graduate mentoring, these were often equated to mentee satisfaction with online graduate mentoring, and, occasionally, faculty satisfaction with the relationship. Further in-depth investigation of strategies for effectiveness and specific outcomes, and what works for specific contexts or mentoring content (e.g., master’s projects, group projects), is needed. Given the increasingly global nature of online education and diversity of online learners, research is also needed on online graduate mentoring that takes into account cultural and epistemological differences between the faculty mentor and student mentee. Perhaps “a new framework, model, and theory are needed in order to give purpose and direction to the transformational potential” (Ambrose & Williamson Ambrose, 2013, p. 79) and unique affordances of online graduate mentoring.

The literature reviewed emphasized a need for professional development and awareness on the part of both faculty who are mentoring students online and students participating in mentoring online. Institutions can provide some or all of the following: (a) orientations to online mentoring; (b) webinars or workshops on best practices for online mentors and for online mentees; and (c) workshops and tutorials on technologies that are current, available to faculty and students at that specific institution, and how those can be best used for different purposes. Additionally, online resources to help faculty and their student mentees as well as incentives for faculty with a high online mentoring workload could contribute to more effective and satisfying mentoring relationships.

Ambrose, A. G., & Williamson Ambrose, L. (2013). The blended advising model: Transforming advising with eportfolios. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(1), 75-89. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1107822

An, S., & Lipscomb, R. (2013). Instant mentoring: Sharing wisdom and getting advice online with e-mentoring. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113(5), S32-S37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.06.019

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing environment. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2). https://auspace.athabascau.ca/handle/2149/725

Andrew, M. (2012). Supervising doctorates at a distance: Three trans-Tasman stories. Quality Assurance in Education, 20(1), 42-53. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881211198239

Barnes, B. J., & Austin, A. E. (2009). The role of doctoral advisors: A look at advising from the advisor’s perspective. Innovative Higher Education, 33(5), 297-315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-008-9084-x

Bender, S., Rubel, D. J., & Dykeman, C. (2018). An interpretive phenomenological analysis of doctoral counselor education students’ experience of receiving cybersupervision. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 11(1). https://repository.wcsu.edu/jcps/vol11/iss1/7

Berg, G. (2016). The dissertation process and mentor relationships for African American and Latina/o students in an online program. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(4), 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1227191

Bierema, L. L., & Merriam, S. B. (2002). E-mentoring: Using computer mediated communication to enhance the mentoring process. Innovative Higher Education, 26(3), 211-227. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017921023103

Broome, M. E., Halstead, J. A., Pesut, D. J., Rawl, S. M., & Boland, D. L. (2011). Evaluating the outcomes of a distance-accessible PhD program. Journal of Professional Nursing, 27(2), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2010.09.011

Byrnes, D., Uribe-Flórez, L. J., Trespalacios, J., & Chilson, J. (2019). Doctoral e-mentoring: Current practices and effective strategies. Online Learning Journal, 23(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i1.1446

Columbaro, N. L. (2009). e-Mentoring possibilities for online doctoral students: A literature review. Adult Learning, 20(3-4), 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/104515950902000305

Crawford, L. M., Randolph, J. J., & Yob, I. M. (2014). Theoretical development, factorial validity, and reliability of the online graduate mentoring scale. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 22(1), 20-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2014.882603

de Beer, M., & Mason, R. B. (2009). Using a blended approach to facilitate postgraduate supervision. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(2), 213-226. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290902843984

de Janasz, S. C., & Godshalk, V. M. (2013). The role of e-mentoring in protégés’ learning and satisfaction. Group & Organization Management, 38(6), 743-774. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601113511296

Deshpande, A. (2016). A qualitative examination of challenges influencing doctoral students in an online doctoral program. International Education Studies, 9(6), 139. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1103528

Deshpande, A. (2017). Faculty best practices to support students in the ‘virtual doctoral land.’ Higher Education for the Future, 4(1), 12-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631116681211

Doyle, N., Jacobs, K., & Ryan, C. (2016). Faculty mentors’ perspectives on e-mentoring post-professional occupational therapy doctoral students. Occupational Therapy International, 23(4), 305-317. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1431

Duffy, J., Wickersham-Fish, L., Rademaker, L., & Wetzler, E. (2018). Using collaborative autoethnography to explore online doctoral mentoring: Finding empathy in mentor/protégé relationships. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 2(1), 57-76. http://www.ejecs.org/index.php/AJQR/article/view/161

Erichsen, E., Bolliger, D. U., & Halupa, C. (2014). Student satisfaction with graduate supervision in doctoral programs primarily delivered in distance education settings. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 321-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709496

Ghani, F. (2020). Remote teaching and supervision of graduate scholars in the unprecedented and testing times. Journal of the Pakistan Dental Association, 29 (Suppl. 2020), S36-S42. https://doi.org/10.25301/JPDA.29S.S36

Griffiths, M., & Miller, H. (2005). E-mentoring: Does it have a place in medicine? Postgraduate Medical Journal, 81(956), 389-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2004.029702

Jacobs, K., Doyle, N., & Ryan, C. (2015). The nature, perception, and impact of e-mentoring on post-professional occupational therapy doctoral students. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 29(2), 201-213. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2015.1006752

Jameson, C., & Torres, K. (2019). Fostering motivation when virtually mentoring online doctoral students. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 9(1), 331-339. https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2019.09.1.23

Khan, R., & Gogos, A. (2013). Online mentoring for biotechnology graduate students: An industry-academia partnership. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17(1), 89-107. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1011366

Kumar, S., & Coe, C. (2017). Mentoring and student support in online doctoral programs. American Journal of Distance Education, 31(2), 128-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2017.1300464

Kumar, S., & Johnson, M. (2017). Mentoring doctoral students online: Mentor strategies and challenges. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 25(2), 202-222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2017.1326693

Kumar, S., & Johnson, M. (2019). Online mentoring of dissertations: the role of structure and support. Studies in Higher Education, 44(1), 59-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1337736.

Kumar, S., Johnson, M., & Hardemon, T. (2013). Dissertations at a distance: Students’ perceptions of online mentoring in a doctoral program. International Journal of E-Learning &Distance Education, 27(1). http://ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/835

Lechuga, V. M. (2011). Faculty-graduate student mentoring relationships: Mentors’ perceived roles and responsibilities. Higher Education, 62(6), 757-771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9416-0

Nasiri, F., & Mafakheri, F. (2015). Postgraduate research supervision at a distance: A review of challenges and strategies. Studies in Higher Education, 40(10), 1962-1969. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.914906

Pardo, J. C., Ramon, D., Stefanelli-Silva, G., Elegbede, I., Lima, L. S., & Principe, S. C. (2020). Advancing through the pandemic from the perspective of marine graduate researchers: Challenges, solutions, and opportunities. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7, 528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00528

Rademaker, L. L., Duffy, J. O. C., Wetzler, E., & Zaikina-Montgomery, H. (2016). Chair perceptions of trust between mentor and mentee in online doctoral dissertation mentoring. Online Learning Journal, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v20i1.605

Ross, J., & Sheail, P. (2017). The ‘campus imaginary’: Online students’ experience of the masters dissertation at a distance. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(7), 839-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1319809

Roumell, E. A. L., & Bolliger, D. U. (2017). Experiences of faculty with doctoral student supervision in programs delivered via distance. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 65(2), 82-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/07377363.2017.1320179

Schichtel, M. (2010). Core-competence skills in e-mentoring for medical educators: A conceptual exploration. Medical Teacher, 32(7), e248-e262. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.489126

Schroeder, S. M., & Terras, K. L. (2015). Advising experiences and needs of online, cohort, and classroom adult graduate learners. NACADA Journal, 35(1), 42-55. https://doi.org/10.12930/NACADA-13-044

Stein, D., & Glazer, H. R. (2003). Mentoring the adult learner in academic midlife at a distance education university. American Journal of Distance Education, 17(1), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15389286AJDE1701_2

Suciati. (2011). Student preferences and experiences in online thesis advising: A case study of Universitas Terbuka. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 12(3), 215-228. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ965078

Sussex, R. (2008). Technological options in supervising remote research students. Higher Education, 55(1), 121-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9038-0

Welch, S. (2017). Virtual mentoring program within an online doctoral nursing education program: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijnes-2016-0049

Mentoring Graduate Students Online: Strategies and Challenges by Rhiannon Pollard and Swapna Kumar, EdD is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.