Volume 23, Number 2

Daniel Villar-Onrubia, Ph.D.

Coventry University, UK

This study looks at OpenCourseWare (OCW) in Spain, a country where most public universities have tried to promote that particular model of open educational resources (OER) provision among academics. Using three universities with varying levels of OCW activity as a case study, this article examines key drivers behind the implementation of OCW initiatives and unpacks what it means, as an academic practice, to engage in OCW authoring. Following a qualitative case study approach and a multi-methods design, this study offers a basis for theoretical generalisations that can be useful for understanding similar dynamics taking place within different organisational contexts in Spain and beyond. The findings reveal a major disconnect between the drive to implement OCW initiatives in Spain and actual opportunities for academics to engage with them as part of their work. The author concludes that the extrapolation of a highly prescriptive model of OER provision into institutional realities different from the context where it was originally devised—in this case, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States—is rather problematic. The article also provides some recommendations to university leaders and policy makers, encouraging the creation of alternative models that are mindful of the institutional and cultural specificities of their own contexts and also to take into consideration the social and material realities of the communities they aim to provide with lifelong learning opportunities.

Keywords: OpenCourseWare, OCW, open educational resources, OER, open educational practices, OEP, open education, higher education, universities, Spain

Over the last two decades, the creation of open educational resources (OER) in higher education (HE) has generated a considerable amount of attention worldwide. A major milestone in the history of OER was the launch of the OpenCourseWare (OCW) initiative by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), conceived as a “free and open digital publication of high quality educational materials, organized as courses” (Carson, 2009, p. 27). Soon after, other universities in countries around the globe became interested in replicating that OER provision model (Carson & Forward, 2010), and Spain quickly stood out due to an extraordinarily high number of institutions in the country doing so (Aranzadi & Capdevila, 2011).

Most public universities in Spain implemented an OCW initiative between 2006 and 2010, but this fact may result in misleading conclusions about the actual importance and long-term uptake of OCW authoring in the Spanish higher education context. The number of Spanish universities in the OCW Consortium started to dwindle in 2014, and currently, the majority of OCW sites “are not up to date, they redirect to other university systems, or they are no longer operational” (Santos-Hermosa et al., 2020, p. 6).

The amount of research on OCW—and more generally OER—in Spain has been modest, and most studies were published several years ago. They include descriptive accounts of the implementation of OCW initiatives at particular universities (Clifton et al., 2013; Gallardo Paúls, 2008; Llorens et al., 2010; Ros et al., 2014) and comparative studies focused on technical features or the nature and structure of content (Borrás Gené, 2010; Llorente Cejudo et al., 2013). Two research projects on the impact of OCW in Spain and Latin America were funded by the Spanish Government (Frías-Navarro et al., 2010; Tovar et al., 2013).

The purpose of this study was to research the interplay between the OCW model and the institutional arrangements influencing academics’ behaviour at Spanish universities. Using three universities as a case study, this article focuses on what it means to be an OCW author in those contexts and the role of OCW authoring as an academic practice, offering a basis for theoretical generalisations that can be useful for understanding similar dynamics at different organisational contexts in Spain and beyond. Additionally, the role of the Universia organisation and network of universities is considered to have played a key role in the proliferation of OCW initiatives in Spain by establishing a regional consortium (with HE institutions in Latin America and Portugal too) associated with the global OCW Consortium.

The contextualisation for this study is considered next, including the theoretical framing and identification of the research questions addressed by the case study approach, which is used to structure the remainder of the article, before moving to the discussion, conclusions, and recommendations.

In 2001, MIT launched the first OCW initiative, which was aimed at providing the public with access to high-quality OER and covering the entire curriculum of a selection of courses taught to its students, with the ambition to eventually include all undergraduate and graduate courses (Abelson et al., 2021). A major concern during the design and implementation of the initiative was to ensure that it would not undermine in any way the service of MIT as a residential institution, which was always regarded as a high priority (Abelson, 2008). After a consultation process, it became clear that academics could only uptake OCW authoring if the publication process was offloaded to support staff, and therefore, “the plan for implementing OCW had to minimize faculty burden” (Lerman et al., 2008, p. 219). As Lerman and Miyagawa (2002, p. 27) stress, academics “operate essentially at capacity, and doing any new task inevitably means not doing something else.” A sizeable budget was secured to enable the development of OCW courses at a scale (Abelson et al., 2021), and beyond financial resources, another key factor was that the initiative drew on a culture of open sharing that was already deeply entrenched in the MIT academic community (Lerman et al., 2008).

The OCW-MIT initiative was unique in capturing the imagination of policy makers, journalists, and opinion leaders all over the world. It contributed to redefining the open concept in education (Peter & Deimann, 2013) and inspired the coinage of OER as an established term (UNESCO, 2002). Moreover, it triggered other institutions' interest in launching their own OCW initiatives, and MIT collaborated with other universities and organisations to establish the OCW Consortium, which was officially launched in 2006, rebranded as the Open Education Consortium (OEC) in 2014, and again in 2019 as Open Education Global (OEG). Some studies have looked at key factors influencing OCW authoring in specific countries, such as Turkey (Kursun et al., 2014) and Taiwan (Wei & Chou, 2021).

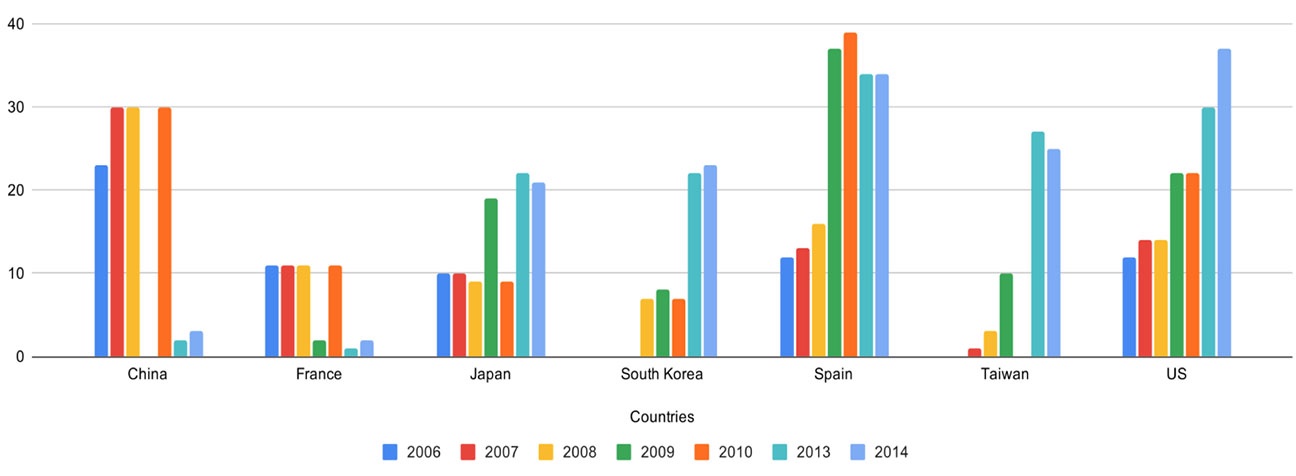

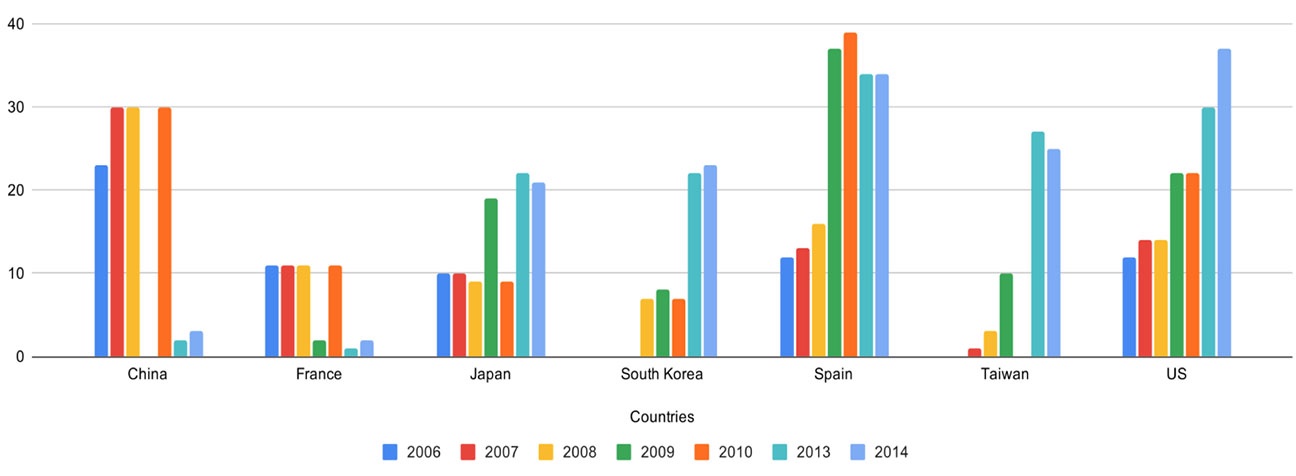

Spain quickly stood out as one of the most active countries in terms of institutional members in the OCW Consortium (Figure 1). However, after 2014, the number of Spanish universities in the OCW Consortium decreased dramatically (Figure 2). In 2021, only six Spanish universities remain in OEG.

Figure 1

Higher Education Institutions in the OCW Consortium per Country

Note. Figure created by the author. It includes only those countries with more than 20 institutional members. Source data collected from the OCW Consortium website (http://ocwconsortium.org) and captures of that site by the Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org).

Figure 2

Spanish Higher Education Institutions in the OCW Consortium (2013-2014), Open Education Consortium (2014-2018), and Open Education Global (2019-2021)

Note. Figure created by the author. Source data collected from the websites of the OCW Consortium (http://ocwconsortium.org/), the Open Education Consortium (http://oeconsortium.org/), Open Education Global (https://www.oeglobal.org) and captures of those sites by the Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org). CC-BY.

Understanding the proliferation of OCW initiatives in Spain requires paying close attention to the advocacy efforts of Universia, an organisation launched in 2000 and sponsored by the Santander Bank—a key financial player with both philanthropic and commercial interests in the HE sector in Ibero-America (Lloyd, 2011). In 2002, Universia and MIT signed an agreement to translate a selection of OCW-MIT courses into Spanish and Portuguese. Later, Universia became one of the first sustaining members of the OCW Consortium and encouraged a dozen Spanish universities to join it, launching OCW-Universia as an associate consortium in 2007 (Aranzadi & Capdevila, 2011).

The lack of incentives associated with OCW authoring, a low level of awareness among academics, and the overall limited resources allocated by universities have been identified as key barriers to the implementation of OCW initiatives in Spain (Frías-Navarro et al., 2010; Tovar et al., 2013).

In addressing the above concerns, the following research questions guided this study:

A socio-technical perspective in line with the principles of social informatics (Meyer et al., 2019) was used as a “theoretical foundation for addressing e-learning, deriving ... from the sociology of contemporary culture, particularly where it intersects with computing use by groups, organizations, communities, and societies” (Andrews & Haythornthwaite, 2007, p. 27). This approach was adopted to develop a more nuanced and context-aware understanding of technologies in use, offering an alternative to deterministic accounts often found in education and technology (EdTech) discussions (Oliver, 2011).

More specifically, the study viewed OCW initiatives as socio-technical interaction networks: “A Socio-Technical Interaction Network (STIN) is a network that includes people (including organizations), equipment, data, diverse resources (money, skill, status), documents and messages, legal arrangements and enforcement mechanisms, and resource flows” (Kling et al., 2003, p. 48). STIN models help one to grasp the intricacies of technology-mediated human behaviour by shedding light upon both technological systems and social factors, which are accounted for as highly enmeshed phenomena, and have proven relevant to the study of education and technology (Creanor & Walker, 2012; McCoy & Rosenbaum, 2019; White et al., 2020).

Instead of focusing on the analysis of technical platforms and the potential activities enabled by them, this study examines the manifold dynamics, processes, and practices that bring these socio-technical arrangements into being as composite networks made of OCW authors, technicians, policy makers, advocates, technical protocols, and others. The STIN framework provides a set of heuristics that can help to articulate the inquiry on socio-technical systems at various levels, prompting researchers to identify a “relevant population of system interactors, core interactor groups, incentives, excluded actors and undesired interactions, existing communication forums, system architectural choice points, resource flows [and then] map architectural choice points to socio-technical characteristics” (Kling et al., 2003, p. 57).

While the STIN strategy was used to map out key elements and relationships around OCW initiatives, the interpretive process—that is, making sense of the practices and perspectives of people involved in those initiatives—was grounded in a set of principles underpinning social informatics and cognate with a socio-materiality lens (Orlikowski & Scott, 2008).

Drawing on the STIN framework, the research adopted a qualitative case study approach and followed a multi-methods design (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Miles & Huberman, 1994), involving the analysis of discourse and behaviour as embodied in (a) documents of different kinds, (b) the accounts provided by research participants, and (c) online data. It addressed the three research questions by investigating OCW authoring within its real-life context, examining several organisations within a bounded system over time through in-depth data collection and drawing on diverse information sources (Creswell, 2007; Yin, 2003).

The study started with a review of documents and online data (phase 1) relating to OCW in Spain, followed by in-depth interviews (phase 2) with both OER experts in that country (n = 4) and participants involved in establishing OCW-Universia (n = 3). The analysis of data collected during the first stages informed the design of the interview guides used as part of the subsequent fieldwork, which involved semi-structured interviews with university leaders and professional staff at the three sites of the case study (n = 23) and at other universities in the same regional system (n = 10) (phase 3). The final stage of fieldwork (phase 4) entailed interviewing academics at the three sites (n = 24) who had been involved in authoring OCW courses and other kinds of learning resources available on the Web.

The overall aim to maximise “what we can learn” (Stake, 1995, p. 6) guided the selection of the three universities as well as the wider system in which they are embedded. A “purposeful maximal sampling” (Creswell, 2007, p. 75) strategy was used, aimed at generating a rich account of the interplay between the OCW model of OER provision and the specificities of different institutional settings. The three universities of the case study are anonymised here as UNI-1, UNI-2 and UNI-3, while other key universities analysed for contextual purposes are anonymised as UNI-a, UNI-b, and UNI-c.

Both UNI-1 and UNI-3 are large universities, while UNI-2 is medium sized. The OCW initiatives of those three institutions achieved different levels of activity in terms of number of OCW courses and number of OCW authors. Less than 1% of academics in UNI-1 (i.e., about 30), 3% in UNI-2 (i.e., about 60), and above 10% in UNI-3 (i.e., about 400) had contributed to their respective OCW initiatives.

The selection of research participants followed a purposive sampling strategy to cover different perspectives and to “establish a good correspondence between research questions and sampling” (Bryman, 2008, p. 458). The samples included three groups of key actors: (a) university leaders (i.e., senior management), (b) professional services staff, and (c) academics (Table 1). The academics recruited as participants had been particularly active in authoring OCW modules and, to a lesser extent, other types of OER and online learning materials.

With the aim of gaining insight into the wider context and its influence on the case study sites, interviews were also conducted with participants involved establishing OCW-Universia and university leaders and staff at other Spanish universities in the same regional HE system.

Table 1

Research Participants per Setting and Category

| Organisation | University leaders | Professional staff | OCW authors | Authors of other kinds of learning resources on the Web | Others | Total |

| UNI-1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | - | 14 |

| UNI-2 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 1 | - | 17 |

| UNI-3 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 2 | - | 16 |

| UNI-a | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | 3 |

| UNI-b | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | 3 |

| UNI-c | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | 4 |

| Others | - | - | - | - | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 16 | 17 | 19 | 5 | 7 | 64 |

Note. OCW = OpenCourseWare.

Desk research (phase 1) included analysing policy and strategy documents (statutes, bylaws, manifestos, plans) relevant to OCW authoring at each university and the whole Spanish HE sector. Other relevant sources (i.e., calls for participation, texts about the OCW initiatives available at their respective sites, brochures, press releases) were also analysed. Online data were collected to assess the scale of OCW initiatives, and Webometrics techniques were applied to gain insight into the overall level of attention paid to the notion of OER across Spanish universities (Villar-Onrubia, 2014).

In-depth interviewing was key to both tracing the origins and evolution of the OCW initiatives and gaining insight into the meaning of open educational practices (OEP) as an academic practice. The interviews with OER experts informed the design of the interview guides used with university leaders, staff, and academics, which were tailored to each group and tested before use.

A computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software package was used to manage and examine data sources (i.e., transcribed interviews, documents, Webpages) and involved descriptive and analytical coding stages, handling the texts interpretively, and focusing on core themes, emerging leitmotifs, and causal links (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Richards, 2009).

The study followed quality criteria for qualitative research to ensure rigour and credibility, mainly by grounding interpretive practices on multiple sources of evidence, establishing rapport with participants, returning to them for further clarifications when needed, keeping a clear line between their perspectives and researchers’ observations, and adopting a reflexive approach throughout the entire process of data collection and analysis (Tracy, 2010). Ethical approval was obtained before fieldwork.

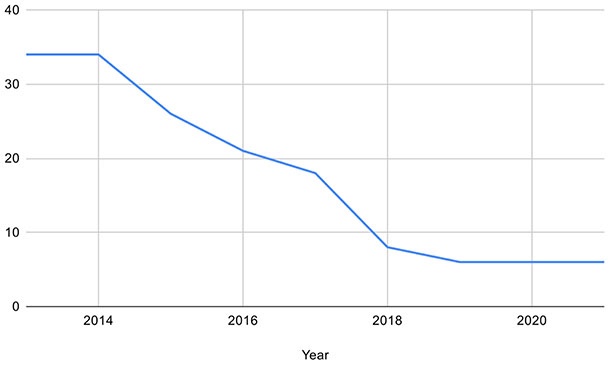

Based on the cross-comparative analysis of the three selected universities and their wider contexts, OCW initiatives were modelled as STINs, and the main potential elements and relationships at play are mapped out in Figure 3.

Figure 3

OCW Initiatives Modelled as Socio-Technical Interaction Networks

Note. Figure created by the author. EdTech = education and technology; OCW = OpenCourseWare; HE = higher education.

Despite the contextual similarities provided by the HE Spanish and regional systems, along with the requirements of the OCW model, there were considerable differences in the implementation of OCW initiatives across the three universities in the study. OCW was not embedded in the same ways and to the same extent into the preexisting institutional arrangements supporting EdTech at each of the three institutions. Table 2 summarises key differences.

Table 2

Key Differences in OpenCourseWare Implementation

| Details | UNI-1 | UNI-2 | UNI-3 |

| Launch date | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 |

| Key actors driving the implementation of OCW | Mid-level institutional leaders | Top-level institutional leaders | Top-level institutional leaders |

| OCW mentioned in top strategic documents | No | No | Yes |

| OCW formally included into EdTech plans | No | Yes | Yes |

| Certificates enabling recognition of OCW authoring in career progression | No | Yes | Yes |

| OCW excellence awards | Yes (only first year) | Yes (over two academic years) | No |

| Instructional design support to OCW authors | Yes (limited) | No | Yes (substantial) |

| Technology | Same as university virtual learning environment | Same as university virtual learning environment | Different from university virtual learning environment |

Note. OCW = OpenCourseWare; EdTech = education and technology.

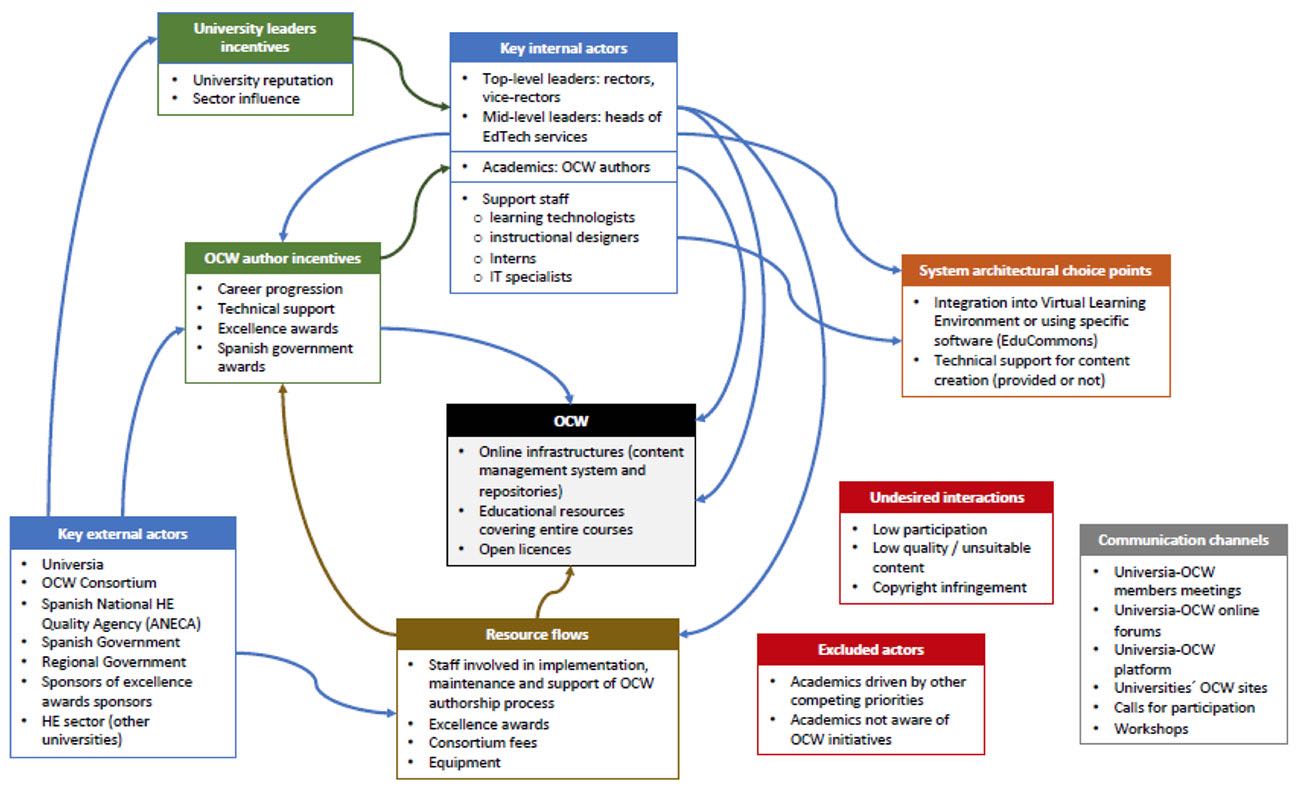

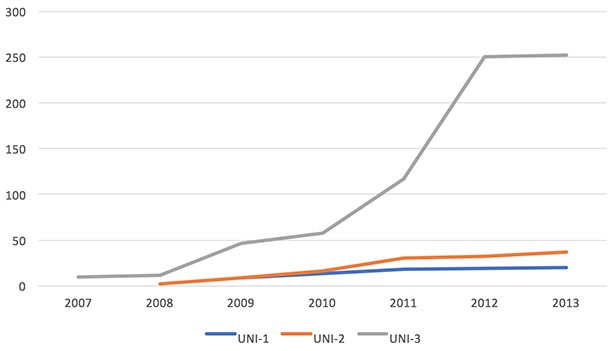

The release of OCW courses at the three universities grew fast during the period following the launch of each initiative, reaching a plateau within the first five years (Figure 4). Growth was negligible after 2013 for the OCW initiatives of both UNI-1 and UNI-3, the former being discontinued in 2017 (with 23 courses) and the latter in 2020 (with 253 courses). UNI-2 has released about 10 extra OCW courses since then, and, out of the three OCW sites, it is the only one still available. The creation of OCW modules tended to be one-off activities at the three universities, but some academics were credited as authors in more than one module—namely about 10% at both UNI-1 and UNI-2 and 20% at UNI-3.

Figure 4

Number of OpenCourseWare (OCW) Courses per University

Note. Figure created by the author. Source data collected from OCW sites of each institution and captures of them by the Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org).

In the case of UNI-3, and to a lesser extent UNI-1, instructional designers were available to support the OCW authoring process. Indeed, the provision of that kind of support is key to understanding the large number of OCW courses produced at UNI-3, as any academic wishing to receive assistance in the creation of online resources in the academic year 2009-2010 was required to contribute the resulting content to the OCW initiative. Instructional design support was outsourced to an external company, and the number of OCW courses authored in 2009-2010 was so high that the courses had to be gradually released over the following years, due to limited capacity to process them. The end to instructional design support for OCW authors resulted in the release of just one new course after 2012:

The regular release of OCW [courses] has been discontinued because the team of technicians was disbanded in June 2012. ... The programme depended on a vice-rector who is no longer in post after the appointment of our new rector, and nothing has replaced the actions that led to such a large number of OCW modules. (Senior learning technologist, UNI-3)

There were important differences across the three universities in terms of the extent to which OCW was present in strategic documents, plans, and support mechanisms relating to EdTech and educational innovation. While no key documents from UNI-1 mentioned OCW, both UNI-2 and UNI-3 included OCW in plans devoted to outlining priorities and support mechanisms in that regard. Moreover, top-level university leaders at UNI-3 mentioned OCW within documents defining their vision for the institution.

UNI-3 made OCW a core element in its teaching and learning innovation programme over a number of years. Most notably, in 2009-2010, access to instructional design was restricted to those willing and able to build their online learning resources for the virtual learning environment (VLE) as OCW courses. Over the next couple of years, the amount of support and incentives for OCW authoring at UNI-3 gradually decreased, and the innovation plan approved by a new leadership team in 2013 did not mention OCW at all.

OCW was also embedded into a programme aimed at supporting the creation of online learning resources at UNI-2. The authors of outstanding OCW courses were rewarded with an economic incentive in the 2008-2009 and 2009-2010 academic years, but coinciding with the appointment of a new leadership team, the allocation of budget for that specific purpose was discontinued. Certificates that could be used by academics for career progression purposes started to be issued to OCW authors at UNI-2 after the first year of activity, and they became the main way of fostering participation after economic incentives were discontinued.

The varying levels of importance from a strategic point of view also translated into significant differences in terms of resources allocated to operational costs and OCW authoring. For instance, while UNI-3 allocated substantial human resources to instructional design support and the implementation of required online infrastructures, UNI-1 and UNI-2 relied largely on the work of interns:

We assigned too much responsibility to the intern, because we didn’t have any member of the staff available to do the job. So it was delayed. Indeed, there were [authors] who had finished their materials, but they were not available to the public on the Website. (Former top-level university leader, UNI-2)

Optimising resources was also part of the rationale for UNI-1 and UNI-2 to use the same technical systems to run their OCW and VLE. While it required some tailoring to meet the requirements of the OCW model, that work could be done in-house as it was an open-source system, and both institutions had the required expertise. On the contrary, at UNI-3, it was not possible to integrate OCW with its proprietary VLE system, and a separate content management system was used instead.

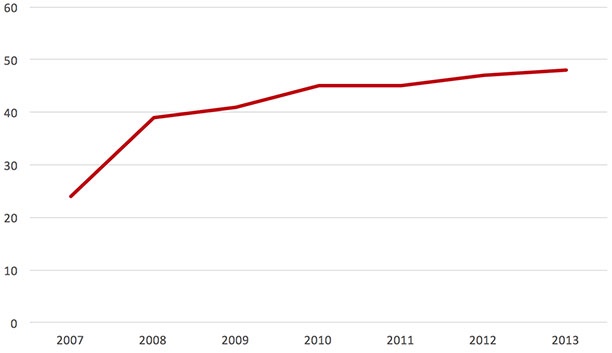

Universia had a strong influence on the implementation of OCW initiatives in Spain, especially among public universities. Most institutions in the OCW-Universia regional consortium joined it between 2007 and 2008, but the number kept growing until 2013 (Figure 5). In 2017, 40 public and 7 private Spanish universities were listed as members on the OCW-Universia site, which is no longer available.

Figure 5

Spanish Higher Education Institutions in OCW-Universia

Note. Figure created by the author. Source data collected from the OCW-Universia site (http://ocw.universia.net) and captures of that website by the web.archive.org.

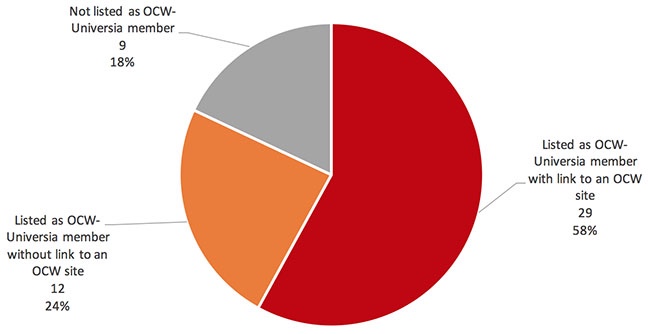

In order to join the OCW-Universia consortium, HE institutions were required to sign a memorandum of understanding and commit to implementing an OCW initiative with at least 10 courses in the first two years. However, not all of the member institutions completed the process of establishing their OCW sites In 2018, most public universities in Spain (more than 80%) were listed as members of the OCW-Universia on its Website, but only 29 active OCW sites (58% public universities) were linked from there (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Public Spanish Higher Education Institutions in OCW-Universia

Note. Figure created by the author. Source data collected from the OCW-Universia website, captured by the Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org/web/20180126044851/http://ocw.universia.net/es/instituciones-integrantes-iberoamericanas-opencourseware.php). Total number of public higher education institutions in Spain provided by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (2019). OCW = OpenCourseWare.

Top-level university leaders at both UNI-2 and UNI-3 had strong links with Universia, as indicated by the fact that representatives from both universities joined its board of directors around the time their institutions became affiliated with the OCW-Universia associate consortium. The decision for their universities to join the consortium must be understood in the context of the overall relationship between those institutions and the Universia organisation and network, as well as the Santander Group as its main sponsor. Besides the aims and values associated with the OCW initiative, cooperating with Universia was somehow a strategic movement on its own:

There is a key factor in the implementation [of the OCW site]: the ongoing relationship between the university and the Santander Bank. The rector was one of the members of Universia’s board of directors, and Santander, through Universia, wanted [us] to implement that initiative. (Former top-level university leader, UNI-2)

The fact that so many Spanish universities had quickly joined OCW-Universia also operated as extra pressure, as not embracing OCW could be perceived as a failure to follow “cutting-edge” trends:

It is also a bit like a domino effect. When you see someone else doing it you say: “Ah, that’s all right to do that, we’ll do it too.” Or because you get some complaints: “If X University is doing it, why is that you are not doing it?” (Top-level university leader, UNI-1)

The authoring of OCW courses does not necessary imply an understanding or even awareness of the basic principles of OER. While some interviewees were cognizant of the philosophical, legal, and technical aspects underpinning OCW as a type of OER, others simply equated OCW authoring with the creation on online learning resources. As an extreme example of this, one of the OCW authors interviewed at UNI-3 was disconcerted at realising during the interview that their OCW modules were accessible to people outside their university. Despite the scale of UNI-3’s OCW and availability of instructional design support and training, the rationale behind OER provision was not clearly communicated to academics:

It hasn’t been [clearly] explained, saying, “Well, we will do either some technical training that includes a clear introduction to the context”—that is, what the values of the project are, to understand why we’re doing this, [why] we’re going to participate in this—or [even] simply some campaign. (Senior learning technologist, UNI-3)

Even though UNI-1 was the only participating university accompanying the launch of its OCW initiative with a series of workshops aimed at raising awareness of the historic, legal, technical, and philosophical implications of OER, dissemination efforts were rather limited:

If you organise a few workshops but then you spend a whole year before circulating anything [again]or organising another workshop, then it is normal for people to think that [the project] is dead. Dissemination is very important and probably those other universities [that have been more successful in finding OCW authors] have done so. I must recognise that we haven’t done enough publicity. Not just workshops, but sending e-mails, advertising it on the homepage of the university’s Website. (Mid-level university leader, UNI-1)

OCW authors at the three institutions were particularly concerned about the creation of online learning resources for their students as a way to enhance learning and overcome the limitations of pedagogical approaches primarily based on academics giving lectures and students taking notes, which have historically dominated teaching and learning at Spanish universities. That level of dedication to authoring learning resources was not regarded by participants as a mainstream academic practice in Spain, but they considered it a core aspect of who they were as academics:

I have created [learning] materials since I started. Always, always ... whether I was working part-time or full-time ... I’ve always elaborated my own [extended] notes. ... It’s absurd to have students taking notes during classes. ... It looks to me like a waste of time. (Academic, UNI-2)

Likewise, academics in certain disciplines tend to base their teaching on original content created by them, and therefore amenable to be released under an open licence, while others heavily rely on the use of copyrighted materials (e.g., artworks). Indeed, the need to rely on copyrighted materials was perceived as an important barrier to OCW authoring. While OCW courses were largely a by-product of academics’ ongoing work on the creation of learning resources, meeting the requirements of the OCW model required extra effort and was a clear barrier to participation: “The thing is that OCW does not require [creating] just a textbook, some notes. ... It also involves creating exercises, self-assessment activities, etc. ... Developing quizzes for self-assessment requires time too” (Academic, UNI-1).

Another impediment mentioned by participants was the perception that sharing teaching aids and other educational resources among peers was at odds with the prevailing academic culture at Spanish universities:

Lecturers are very protective of the materials that they have and [the content] they deliver in their classes. ... I think that it is something cultural, not to meddle in what other colleagues do, because it generates tensions and conflicts. These are sensitive issues. (Academic, UNI-3)

While participants considered the creation of learning resources as an important academic practice, they also recognised that its value for career progression purposes and appraisal was limited. Some felt that their excessive commitment to teaching and creating nonstandard scholarly publications (e.g., blogs, Websites, etc.) had a negative impact on their own opportunities for career development. This was particularly constraining to early-career academics:

Any young academic who doesn’t have a permanent position is currently listening to the following message: “You have to get accredited; you must publish a lot of research work.” It’s quite clear what she needs to do if she wants to have access to a [permanent] position in a reasonable time frame. Probably not to create OCW courses. ... The thing is that within this population that cannot devote their time [to the creation of OER] there are more people convinced that this is the future of the university. But they have to combine the future of the university and their own future. (Former top-level university leader, UNI-2)

Even though the value attached to the creation of online learning resources for career progression—and more generally, teaching as compared to research—was relatively low, the effort of adapting content to the OCW requirements was more worthwhile at UNI-2 and UNI-3 thanks to the issuing of certificates to OCW authors:

What they always say when you are planning to go for an accreditation is that you have to try and tick all the boxes, not to leave any gaps. ... Everyone knows that research is the most important section. As for the teaching section, provided you have taught enough credits—there is a minimum—[you are fine], then the rest is just complementary. ... You may meet the requirements of the teaching section just with your classes. ... Innovation in teaching is far from being a decisive factor [but still counts]. (Academic, UNI-2)

While most senior academics would not themselves benefit directly from that kind of recognition, one motivation for some was to help younger colleagues by coauthoring OCW courses with them. Other motivations apart from direct incentives (e.g., support, certificates) were social pressure (e.g., being invited personally) or involvement in the implementation of OCW and having to therefore set an example.

The findings from this case study are consistent with the cumulative body of knowledge generated in the social informatics literature (Meyer et al., 2019). In particular, this study uncovered some of the main difficulties that may arise when an EdTech initiative originally designed for a specific institution, namely OCW-MIT, is extrapolated to significantly different contexts. In doing so, it approached EdTech as socio-technical arrangements formed by a diverse range of interrelated elements, including artefacts (such as hardware and software), people, roles, values, practices, norms, and protocols (Kling, 2007).

This study’s results are also in line with the results of previous research on OEP that highlight the importance of institutional arrangements and cultures (Cachia et al., 2020; Cox, 2013; Hatakka, 2009; King et al., 2018) and complement, with qualitative insights, the results from previous studies on OCW in Spain (Frías-Navarro et al., 2010; Tovar et al., 2013).

An analysis of the meaning and value attached to OCW authoring as an academic practice across the institutions in this study revealed key aspects influencing the dispositions of academics towards OEP uptake, the long-term sustainability of those initiatives, and the more or less successful ways of fostering participation.

The analysis revealed five main differences between OCW-MIT and the OCW initiatives examined in this case study:

Overall, a disconnect was observed between the drivers and rhetoric behind the implementation of OCW initiatives and the motivations for academics to create OCW courses. Different motives may intersect at the creation and release of OER, often resulting in tensions and conflicting priorities (Falconer et al., 2016). As noted by Selwyn (2013, p. 82), “it may be argued that the likelihood of teachers and learners involved in the production of open software or content is curtailed by the realities of institutionalized education—not least issues of time, technical expertise, interest and motivation.” Even when there is appetite to create OER, the day-to-day demands of established academic practices—including a host of administrative tasks—leave little room for doing so.

The lack of incentives is a clear barrier to OCW authoring in Spain (Frías-Navarro et al., 2010), and, beyond the particularities of each of the three selected universities and their own institutional arrangements, the value—for career progression—of producing online learning resources was minimal, as determined by performance criteria established at a national level for the entire Spanish HE system. This means that academics had to prioritise other kinds of academic activities, mainly publishing research, over OCW authoring if they were to advance in their careers.

However, the two universities in the case study that provided OCW authors with a certificate enabling them to get their work recognised in accreditation processes—even if the value was minimal—achieved higher levels of participation. Academics aspiring to be promoted to more senior positions would benefit from prioritising other types of outputs; but at the same time, an OCW certificate was more valuable to them than it was to senior colleagues. Beyond career progression implications, making access to instructional design support for the creation of online learning materials conditional to the release of the resulting resources as OCW courses made the biggest difference in terms of participation levels across the three universities. That type of support was key to the implementation of OCW-MIT and has been highlighted in previous studies as an important enabler of OER authoring (Henderson & Ostashewski, 2018; Ros et al., 2014; Wei & Chou, 2021).

Using three OCW initiatives in Spain as a case study, this article sheds light on the process of implementing a highly predefined model of OER provision within institutional contexts that are considerably different from where it was originally devised, namely MIT. The study reveals a major disconnect between the drive to implement the initiatives and the realities of adopting OCW authoring as an academic practice. Even though the availability of support and the issuing of certificates—which academics may use for career progression purposes—proved to be valuable mechanisms used by some of the universities as enablers of OCW authoring, the overall incentive to invest time and effort in OER provision was minimal due to the accreditation and performance criteria defined at a national level.

An important recommendation for university leaders and policy makers wishing to promote the authoring and release of OER is to devise models that take into consideration the specificities of their institutions and the wider HE system in which they operate, paying particular attention to ways of making participation a valuable academic practice in relation to other competing priorities. For those considering the implementation of a highly defined model of OER provision conceived elsewhere—such as OCW—it is advisable to invest time first into assessing the readiness of their communities for the uptake of the proposed OEP (Wei & Chou, 2021) and carefully examining their institutional contexts from a socio-technical perspective.

The implementation of OER initiatives, including OCW, and related learning opportunities, such as massive open online courses, is often driven by the honourable goal of widening access to education and enabling development opportunities and lifelong learning for all; however, despite good intentions, it may instead lead to reinforcing knowledge gaps and social inequalities (Knox, 2013; Rohs & Ganz, 2015) by wrongly putting too much emphasis on individual agency over social structures (Eynon & Malmberg, 2021). Therefore, university leaders, policy makers, and advocates should take a step back to consider the ultimate goal they want to achieve in relation to their institutions’ missions before deciding what type of OER initiative is the most suitable to implement or promote, and even whether OER provision is the best way of doing so.

The author acknowledges funding from Talentia Excellence Grants (Junta de Andalucia), the Oxford Internet Institute, the University of Oxford’s Santander Academic Travel Award and the Carr & Stahl Fund (St Antony’s College, University of Oxford) for the PhD research on which this paper is based. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abelson, H. (2008). The creation of OpenCourseWare at MIT. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17(2), 164-174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-007-9060-8

Abelson, H., Miyagawa, S., & Yue, D. K. P. (2021, May 24). On the 20th anniversary of OpenCourseWare: How it began. MIT Faculty Newsletter, 33(5). https://fnl.mit.edu/may-june-2021/on-the-20th-anniversary-of-opencourseware-how-it-began/

Andrews, R., & Haythornthwaite, C. (Eds.). (2007). The SAGE handbook of e-learning research. Sage Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-sage-handbook-of-e-learning-research/book243430

Aranzadi, P., & Capdevila, R. (2011). Open Course Ware, recursos compartidos y conocimiento distribuido. La Cuestión Universitaria, 7, 126-133. http://polired.upm.es/index.php/lacuestionuniversitaria/article/view/3398

Borrás Gené, O. (2010). Observatorio de plataformas para OCW. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Cachia, R., Aldaoud, M., Eldeib, A., Hiari, O., Tweissi, A., Villar-Onrubia, D., Wimpenny, K., & Maya, I. (2020). Cultural diversity in the adoption of open education in the Mediterranean basin: Collectivist values and power distance in the universities of the Middle East. Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política, Humanidades y Relaciones Internacionales, 22(44), 53-82. https://doi.org/10.12795/araucaria.2020.i44.03

Carson, S. (2009). The unwalled garden: Growth of the OpenCourseWare Consortium, 2001-2008. Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 24, 23-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510802627787

Carson, S., & Forward, M. L. (2010). Development of the OCW Consortium. In 2010 IEEE Education Engineering (EDUCON) (pp. 1657-1660). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2010.5492401

Clifton, J., Díaz Fuentes, D., Fernández Gutiérrez, M., & Revuelta López, J. (2013). Difusión del proyecto OpenCourseWare—Universidad de Cantabria en asignaturas relativas a la economía mundial. In M. A. Bringas Gutiérrez, M. Fernández Gutiérrez, & M. Fernández Redondo (Eds.), XV Reunión de Economía Mundial / Sociedad de Economía Mundial (pp. 5-10). Universidad de Cantabria. http://hdl.handle.net/10902/4425

Cox, G. (2013). Researching resistance to open education resource contribution: An activity theory approach. E-Learning and Digital Media, 10(2), 148-160. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2013.10.2.148

Creanor, L., & Walker, S. (2012). Learning technology in context: A case for the sociotechnical interaction framework as an analytical lens for networked learning research. In L. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, V. Hodgson, & D. McConnell (Eds.), Exploring the theory, pedagogy and practice of networked learning (pp. 173-187). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0496-5_10

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-13099-000

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 1-19). Sage Publications. https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/40425_Chapter1.pdf

Eynon, R., & Malmberg, L.-E. (2021). Lifelong learning and the Internet: Who benefits most from learning online? British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(2), 569-583. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13041

Falconer, I., Littlejohn, A., McGill, L., & Beetham, H. (2016). Motives and tensions in the release of open educational resources: The UKOER program. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2258

Frías-Navarro, M. D., Pascual Llobell, J., Monterde i Bort, H., Pascual Soler, M., Badenes Ribera, L., & Pascual Mengual, J. (2010). Impacto del Open Course Ware (OCW) en los docentes universitarios. Universidad de Valencia/Ministerio de Educación. https://perma.cc/H49P-UFTZ

Gallardo Paúls, B. (2008). Teaching and open access: The Open Course Ware of the Universitat de València. @tic. Revista d’innovació Educativa, 1, 16-25. http://ojs.uv.es/index.php/attic/article/view/45

Hatakka, M. (2009). Build it and they will come?—Inhibiting factors for reuse of open content in developing countries. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 37(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2009.tb00260.x

Henderson, S., & Ostashewski, N. (2018). Barriers, incentives, and benefits of the open educational resources (OER) movement: An exploration into instructor perspectives. First Monday, 23(12). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i12.9172

King, M., Pegrum, M., & Forsey, M. (2018). MOOCs and OER in the Global South: Problems and potential. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(5). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i5.3742

Kling, R. (2007). What is social informatics and why does it matter? The Information Society, 23(4), 205-220. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240701441556

Kling, R., McKim, G., & King, A. (2003). A bit more to it: Scholarly communication forums as socio-technical interaction networks. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 47-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10154

Knox, J. (2013). Five critiques of the open educational resources movement. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8), 821-832. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.774354

Kursun, E., Cagiltay, K., & Can, G. (2014). An investigation of faculty perspectives on barriers, incentives, and benefits of the OER movement in Turkey. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(6). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i6.1914

Lerman, S. R., & Miyagawa, S. (2002). OpenCourseWare: A case study in institutional decision making. Academe, 88(5), 23-27. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ655807

Lerman, S. R., Miyagawa, S., & Margulies, A. H. (2008). OpenCourseWare: Building a culture of sharing. In T. Iiyoshi & M. S. V. Kumar (Eds.), Opening up education: The collective advancement of education through open technology, open content, and open knowledge (pp. 213-227). MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/opening-education

Llorens, F., Bayona, J. J., Gómez, J., & Sanguino, F. (2010). The University of Alicante’s institutional strategy to promote the open dissemination of knowledge. Online Information Review, 34(4), 565-582. https://doi.org/10.1108/14684521011072981

Llorente Cejudo, M. del C., Cabero Almenara, J., Vázquez Martínez, A. I., & Alducín Ochoa, J. M. (2013). Proyecto OpenCourseWare y su implantación en universidades andaluzas, 12(1), 11-21. http://dehesa.unex.es/handle/10662/724

Lloyd, M. (2011, July 10). Billion-dollar benefactor for campuses in Latin America: A Spanish bank. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/billion-dollar-benefactor-for-campuses-in-latin-america-a-spanish-bank/

McCoy, C., & Rosenbaum, H. (2019). Uncovering unintended and shadow practices of users of decision support system dashboards in higher education institutions. Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 70(4), 370-384. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24131

Meyer, E. T., Shankar, K., Willis, M., Sharma, S., & Sawyer, S. (2019). The social informatics of knowledge. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(4), 307-312. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24205

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-97407-000

Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. (2019). Datos y cifras del sistema universitario Español 2018-2019 (Data and figures of the Spanish university system 2018-2019). Gobierno de España. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:2af709c9-9532-414e-9bad-c390d32998d4/datos-y-cifras-sue-2018-19.pdf

Oliver, M. (2011). Technological determinism in educational technology research: Some alternative ways of thinking about the relationship between learning and technology. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(5), 373-384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00406.x

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2008). Sociomateriality: Challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 433-474. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520802211644

Peter, S., & Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7-14. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.23

Richards, L. (2009). Handling qualitative data: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Rohs, M., & Ganz, M. (2015). MOOCs and the claim of education for all: A disillusion by empirical data. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(6). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i6.2033

Ros, S., Hernández, R., Read, T., Rodrı, M., Pastor, R., & Dı, G. (2014). UNED OER experience: From OCW to open UNED. IEEE Transactions on Education, 57(4), 248-254. https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2014.2331216

Santos-Hermosa, G., Estupinyà, E., Nonó-Rius, B., Paris-Folch, L., & Prats-Prat, J. (2020). Open educational resources (OER) in the Spanish universities. Profesional de la Información, 29(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.nov.37

Selwyn, N. (2013). Distrusting educational technology: Critical questions for changing times. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Distrusting-Educational-Technology-Critical-Questions-for-Changing-Times/Selwyn/p/book/9780415708005

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-art-of-case-study-research/book4954

Tovar, E., López, J., Piedra, N., Sancho, E., & Soto, Ó. (2013). Aplicación de tecnologías Web emergentes para el estudio del impacto de repositorios OpenCourseWare españoles y latinoamericanos en le Educación Superior. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid & Gobierno de España. http://ocw.uc3m.es/informe-final-ocw.pdf/at_download/file

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837-851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

UNESCO. (2002). Forum on the impact of open courseware for higher education in developing countries—Final report. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001285/128515e.pdf

Villar-Onrubia, D. (2014). The value of Web mentions as data: Mapping attention to the notion of OER in the HE arena. In M. Sánchez & E. Romero Frías (Eds.), Ciencias sociales y humanidades digitales técnicas, herramientas y experiencias de e-research e investigación en colaboración (pp. 163-181). Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:0aac8efd-f100-4a06-9fe5-7a1d849120bf

Wei, H.-C., & Chou, C. (2021). Ready to do OpenCourseWare? A comparative study of Taiwan college faculty. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 22(2), 118-142. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v22i2.5252

White, S., White, S., & Borthwick, K. (2020). Blended professionals, technology and online learning: Identifying a socio‐technical third space in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 75(1), 161-174. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12252

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. https://www.worldcat.org/title/case-study-research-design-and-methods/oclc/50866947

"They Have to Combine the Future of the University and Their Own Future": OpenCourseWare (OCW) Authoring as an Academic Practice in Spain by Daniel Villar-Onrubia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.