Volume 24, Number 1

Efrem Melián, José Israel Reyes, and Julio

Meneses

Open University of Catalonia, Spain

The online doctoral population is growing steadily worldwide, yet its narratives have not been thoroughly reviewed so far. We conducted a systematic review summarizing online PhD students’ experiences. ERIC, WoS, Scopus, and PsycInfo databases were searched following PRISMA 2020 guidelines and limiting the results to peer-reviewed articles of the last 20 years, yielding 16 studies eligible. A thematic synthesis of the studies showed that online PhD students are generally satisfied with their programs, but isolation, juggling work and family roles, and financial pressures are the main obstacles. The supervisory relationship determines the quality of the experience, whereas a strong sense of community helps students get ahead. Personal factors such as motivation, personality, and skills modulate fit with the PhD. We conclude that pursuing a doctorate online is more isolating than face to face, and students might encounter additional challenges regarding the supervision process and study/life balance. Accordingly, this review might help faculty, program managers, and prospective students better understand online doctorates’ pressing concerns such as poor well-being and high dropout rates.

Keywords: qualitative review, online higher education, online PhD program, online doctoral student, lived experience, student’s perspective

There has been a dramatic increase in recent years in the number of students enrolled in online doctoral programs (Burrus et al., 2019; Sverdlik et al., 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has only accelerated what was already a strong trend towards virtuality in this educational stage. The most common profile of this population is distinct from the traditional PhD student. Whereas the traditional doctoral candidate was young and studied on site and full-time, the non-traditional candidate is a working adult with family responsibilities pursuing their degree online and part-time (Offerman, 2011).

Historically, the doctoral population has experienced very high attrition and delayed completion rates (Baltes & Brown, 2018; Lovitts, 2001). This situation is even more concerning in the case of online doctorates where dropouts are in the range of 40-70% (Marston et al., 2019; Rigler et al., 2017). But these are not the only potential troubles PhD students might deal with. Recent literature has highlighted what can be considered a mental health epidemic among this population (“Being a PhD Student Shouldn’t Be Bad for Your Health,” 2019; Evans et al., 2018). Poor well-being, high stress, and burnout from overworking are more widespread than previously thought, putting PhD students at an increased risk of developing a psychiatric disorder relative to the general population. These circumstances have dire implications. High attrition rates are costly in personal, institutional, and societal terms (Kelley & Salisbury-Glennon, 2016; Litalien & Guay, 2015). On the one hand, individuals face emotional hardship and might lose personal and professional opportunities. On the other, institutions fail to retain talent and waste their limited resources, while society at large loses the potential for knowledge growth and innovation.

Over the last few decades, a substantial body of research has been conducted on the factors promoting persistence or, alternatively, causing dropout in higher education (Tinto, 1975; Vossensteyn et al., 2015) and doctoral studies (Castelló et al., 2017; Lovitts, 2001; Sverdlik et al., 2018). Scarce research has been devoted, however, to examine this phenomenon in the context of online doctoral programs. Thus, there is a need to address this gap in the understanding of adult learners’ experiences and challenges within the online doctoral environment. Deeper awareness about this student body may help program chairs strengthen their online PhD programs, faculty better comprehend the demands of their students, and future students adjust their expectations about what pursuing an online PhD degree actually entails.

Several reviews have been conducted aiming to understand PhD candidates’ experiences and perspectives (Akojie et al., 2019; Gray & Crosta, 2019; Rigler et al., 2017; Spurlock & Cunningham, 2016; Sverdlik et al., 2018). However, most of them have not focused exclusively on the context of online PhD programs, often pooling together in-person, blended, and online programs. Such approach does not allow us to discern the specific characteristics and challenges a fully online context might exert on students. Akojie et al.’s review (2019) is, thematically, the closest to our own. Nonetheless, these authors exclude part-time students, which we include and consider a crucial profile closely related to adult, non-traditional students. Akojie et al. also limited the timespan to five years, which we expand to the last two decades to grasp a fuller picture of the phenomenon.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to comprehensively examine and critically analyze the available evidence on the experiences and perceptions of PhD students pursuing their degrees in an online modality. We specifically sought to synthesize the aspects facilitating or hampering the doctoral journey and the reasons why these students persist and eventually complete their studies or, alternatively, delay completion or drop out from their programs.

Systematic reviews are the method of choice when aiming to describe a phenomenon, summarize the available evidence, and document the remaining gaps in the literature (Gough & Thomas, 2016). This approach is particularly useful to decision makers. Hence, we adopted this approach while additionally following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021) to report the search and article selection process.

The general research question guiding this review was: What are the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of online PhD students along their doctoral journey? Derived from this broad question, we posed two additional sub-questions: What are the main perceived factors affecting online students’ persistence in their programs? How satisfied are they with the PhD program, the supervisory relationship, and the sense of community?

We searched four scientific databases, accounting for both educational-focused (ERIC) and comprehensive scientific repositories (Web of Science, Scopus, and PsycInfo). Results were limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English from 2002 to 2021. Including research performed over this time span gave us a broad longitudinal picture of the phenomenon. Focusing on primary empirical studies, we excluded literature reviews, grey literature, and anecdotal papers. The search was performed in June 2021 and included three semantic blocks of terms: (PhD OR doctoral OR doctorate) AND (online OR distance OR off-campus) AND (experiences OR perceptions OR attitudes).

The first and second blocks aimed to specify the target population of the search, while the third block aimed at incorporating the type of qualitative results we were seeking. The search string terminology and truncations were deliberately kept simple in order to retrieve the maximum number of articles and to avoid unintended mistakes derived from each database’s particular functioning.

Studies had to meet the following criteria to be included in the review: (a) written in English; (b) from the last 20 years; (c) peer-reviewed; (d) empirical; (e) include online PhD students among its participants; and (f) gather accounts of the participants’ experiences throughout their online PhD programs.

We excluded studies that covered professional doctorates since their characteristics are quite different from research-intensive doctorates. Additionally, we discarded studies that did not collect first-person narratives (either coming from interviews or open-ended questionnaire items) and studies focused on specific courses or interventions that do not address the whole PhD degree.

Once we conducted the database search and retrieved the references, we first imported them to Zotero to manage the whole collection and remove duplicates. Then, we uploaded the collection to Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016), a software tool specifically developed to facilitate collaboration among researchers in the initial screening stages of systematic reviews. The first and second authors carried out a title and abstract screening, discarding thematically non-relevant studies and discussing disagreements about the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, we conducted a full-text reading of the remaining articles which allowed a final selection of articles to be included in this review.

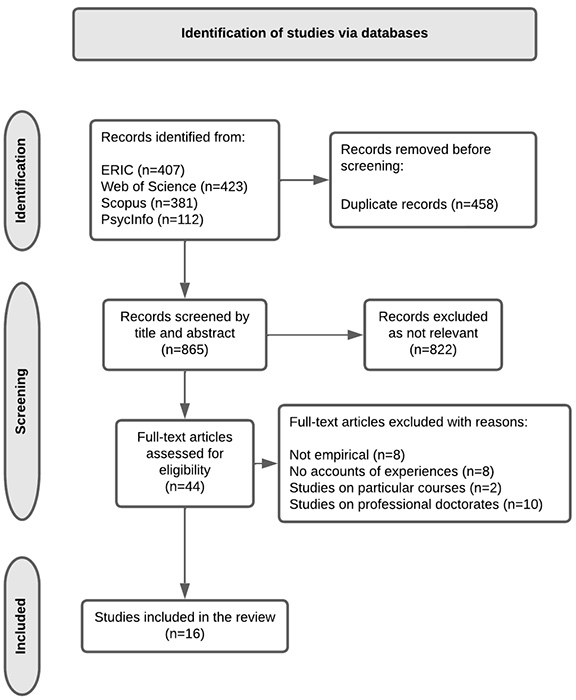

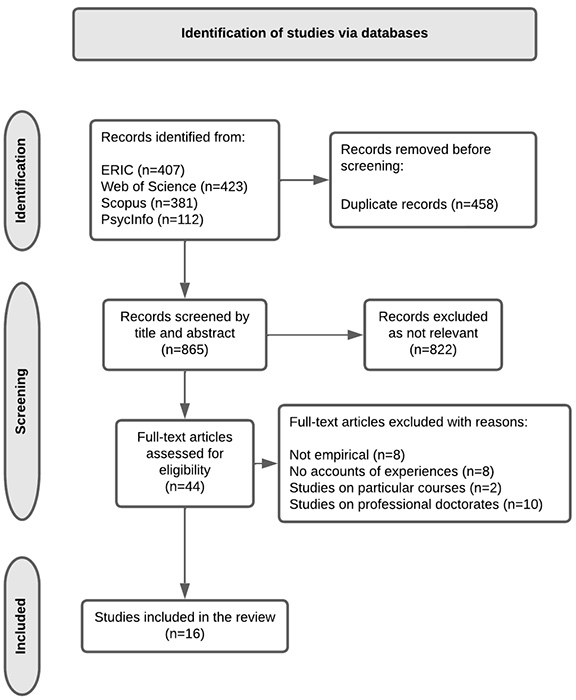

Figure 1 shows the articles’ search and selection procedure following the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021). PRISMA guidelines were developed to ensure detailed and transparent reporting of the review process, allowing for its trustworthiness and reproducibility. We initially recovered 1,323 articles using our search string in all four databases. After removing 458 duplicates, two independent coders screened 865 articles by title and abstract, deeming 43 articles for full-text assessment. After reading the whole text, 27 articles were further discarded due to several reasons such as not being empirical, not including students’ first-person accounts, or referring to interventions or courses and not to the general PhD program. Ultimately, 16 articles were included in the review.

Figure 1

PRISMA 2021 Flowchart

To make sense of the corpus of data, the first and second authors agreed on extracting the following information: bibliographic data (title, authors, year); context (country, field); methodology; participants; aim of the study; domains and themes; main findings; and limitations. We used thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008) to analyze the results sections of the papers. This approach was specifically developed to guide data analysis in qualitative systematic reviews, providing a rigorous framework through a qualitative lens. Following the scheme outlined by Thomas and Harden (2008), we first conducted line-to-line coding of the studies’ findings, while inductively developing a set of codes and descriptive themes that were progressively refined. In a second stage, we interpreted these descriptive themes to generate analytical themes that aimed to cover the whole spectrum of the phenomenon under review. These descriptive and analytical themes will serve as the basis for structuring our analysis in the following section.

Sixteen articles were eligible for inclusion in this review. Table 1 displays the articles’ findings and other key information. Except for one study conducted in Zimbabwe, all studies came from the USA, UK, and Australia. The fields of study gravitated heavily towards education (n = 7), while there were also some papers from medicine (n = 3) and psychology (n = 2). In four studies, the field was not explicitly mentioned. Most studies used a qualitative approach (13 studies with a total of 367 participants), whereas three used mixed methods (801 participants). The most frequent domains were the supervisory relationship (n = 6) and the overall PhD experience (n = 5), while other domains alluded to the sense of community (n = 2), emotions (n = 1), motivation (n = 1), and received support (n = 1).

Table 1

Descriptive Summary of Included Studies

| Citation | Country | Participants | Design: Instrument | Aim of the study | Main findings |

| Andrew (2012) | AU | 3 students | Qualitative: Interviews | Explore the challenges around distance PhD supervision |

Supervision at a distance has the advantage of flexibility and convenience to

reconcile with personal life. It does not hamper creativity, but there is

potential for loneliness.

Peer and institutional support are preconditions for engagement.

|

| Berg (2016) | US | 228 current and recently graduated students | Mixed methods: Survey | Understand the experience of African American and Latinx online PhD students |

Students carefully assess the risks and rewards derived from the decision of

pursuing a doctoral degree.

Challenges in the online doctorate: financial pressures, feelings of

self-doubt, isolation, family, and work responsibilities (70% took an

unscheduled break).

Advantages: demographically blind and culturally diverse.

|

| Brown (2017) | US | 75 students | Qualitative (phenomenology): Interviews | Explore perceived supports that contribute to persistence |

Main reasons for choosing an online program are flexibility, best fit with work

and family schedule, and no need to travel.

Advisors, family members, and co-workers are valuable sources of support.

Excessive workload, and professors’ lack of empathy regarding personal

responsibilities are reasons for quitting.

|

| Byrd (2016) | US | 12 students | Qualitative (phenomenology): Interviews | Understand factors that contribute to students’ sense of community |

Sense of community affects online doctoral experience positively.

Being in a cohort provides security and lessens anxiety.

Initial f2f seminars contribute greatly to togetherness.

Facing challenging situations strengthens the bond between participants.

|

| Erichsen et al. (2014) | US | 295 students | Mixed methods: Survey | Investigate distance doctoral students’ satisfaction with supervision |

Students are moderately satisfied with their supervisors, but many feel

isolated and abandoned.

Men are more satisfied than women. Students in blended programs are more

satisfied than students in online programs.

An online program is harder than a f2f one; but students value flexibility,

freedom, and the sense of empowerment it provides.

|

| Fiore et al. (2019) | US | 18 current and recently graduated students | Qualitative: Interviews |

Understand online doctoral students’ perceptions about supervision and

persistence

|

Supervision is the most cited factor related to persistence.

Many students feel independent research is daunting and feel frustrated with

the lack of or inconsistent advice received.

Students do not expect the loneliness and isolation the doctoral journey

entails.

|

| Halter et al. (2006) | US | 5 students | Qualitative (phenomenology): Interviews | Understand the experience of online doctoral students |

The benefits of an online PhD program (convenience, flexibility) outweigh the

costs (isolation).

Introverted, shy, and independent people fit best.

Students learn new skills such as catching up with technology, communicating

online, and building community.

|

| Ivankova & Stick (2007) | US | 278 current and former students | Mixed methods: Interviews | Identify factors contributing to students’ persistence |

Persistence is affected by program quality, relevance for professional life,

quality advisor’s feedback, and student’s writing skills.

Lack of synchronous and f2f interaction is a dropout factor.

Beneficial instructors are responsive, provide quality advice, and are willing

to accommodate students’ needs.

|

| Jameson & Torres (2019) | US | 40 students |

Qualitative: Survey and interviews

|

Explore mentor-student relationship and its influence on student’s

motivation to persist

|

Internal locus of control is a predictor of persistence.

Students at the early stages are excited and motivated but have unrealistic

expectations and overestimate their skills to conduct independent research.

The relationship with the supervisor is the most rated factor (~75%) in

supporting students’ motivation.

|

| Kennedy & Gray (2016) | UK | 24 students |

Qualitative: Survey and interviews

|

Explore doctoral students’ affective practice within the online environment |

Main positive emotions felt are pleasure, satisfaction, excitement, and

belonging; main negative emotions are upset, frustration, anger, fear.

Emotions circulate around three sites of intensity: sense of personal

progression, interaction with the community, and advisor and peers’

feedback.

|

| Kumar et al. (2013) | US | 9 recently graduated students | Qualitative: Interviews | Identify strategies used to mentor online doctoral students through their dissertation |

Students value mentors using different means of communication and providing

structure, with clear deadlines and expectations. Encouragement, positive

reinforcement, and gentle criticism are motivating.

Challenges: taking mentor’s feedback constructively and acting on it;

developing a “tough skin”; finding time to write; receiving enough

peer support; implementing research at a distance.

|

| Lee (2020) | UK | 13 current and recently graduated students | Qualitative (Phenomenology): Interviews | Explore the experiences of online PhD students |

Students have unrealistic expectations by assuming an online PhD is easier than

a traditional one.

Initial residential activities foster sense of community and help students

overcome their initial feelings of uncertainty.

Students feel increasingly competent as they advance through the dissertation

phase. When graduating, many feel “scholarly” but not

“scholars.”

|

| Madhlangobe et al. (2014) | ZW | 5 PhD and 6 master’s students | Qualitative: Interviews |

Describe motivational factors that increase successful doctoral and

master’s graduation

|

Students take cultural (being labelled a failure by family and friends), social

(self-initiated exile from friends), and financial (borrowing money from loan

sharks) risks.

“Team power,” including family and friends, is a strong predictor

of success.

|

| Natal et al. (2020) | US | 17 students | Qualitative (phenomenology): Interviews | Examine the experiences of Asian and Latinx online doctoral students |

Both Asian and Latinx are collectivists, experience a sense of duty, and rely

on their families to earn their degree.

Asian students feel pressure to attain an “honorable profession.”

Latinx are more likely to be first-generation college students and want to

reduce the stigma associated with their culture.

The online modality erases being perceived as culturally different.

|

| Naylor et al. (2018) | AU | 115 students | Qualitative: Survey | Examine the expectations and experiences of off-campus PhD students |

Students expect the PhD to be time-consuming, challenging, and personally

rewarding; but also, solitary and difficult to balance with personal life.

80% find the experience positive. 70% say they are overworked, but that

perception is unrelated to PhD satisfaction.

Inadequate supervision is heavily linked to a negative PhD experience.

|

| Studebaker & Curtis (2021) | US | 21 current and recently graduated students | Qualitative: Email interview | Explore how institutions can build sense of community in an online doctoral program |

Being part of a cohort and courses’ structure help build sense of

community.

Connections, although mainly asynchronous (e.g., instant messaging, group

chats, video conferencing), contribute to success.

|

Note. AU = Australia. ZW = Zimbabwe. N = 16.

We identified three analytical themes that run through the sixteen reviewed articles: (a) the overall online PhD experience, encompassing students’ expectations, perceived challenges, and satisfaction with the program; (b) relational factors such as the supervisory relationship and the community of peers; and (c) personal factors such as motivation, emotions, skills, and personality.

The online modality allows students to access educational opportunities that would not be available otherwise (Erichsen et al., 2014; Halter et al., 2006). They choose to pursue a doctorate online for a variety of reasons, mainly for the flexibility it provides to work at their own pace and from any location and also for the convenience of not having to travel or commute to campus (Halter et al., 2006). This is essential if we consider the non-traditional profile of most of these students. They are usually working professionals who must reconcile their studies with job and family responsibilities, thus having to juggle multiple roles and usually managing chronic time scarcity. Furthermore, many participants value joining a global community and the networking opportunities it entails (Kennedy & Gray, 2016), while ethnic minority students appreciate the “demographically blind” context (Berg, 2016) that erases perceptions of cultural differences and allows them to be just regular students (Natal et al., 2020).

Prior expectations about the doctorate are rather inaccurate, however. Students frequently underestimate some issues such as the difficulty of online programs compared to traditional ones—with many assuming the former to be somewhat easier—(Lee, 2020), the workload requirements (Brown, 2017), or the level of isolation that working on their thesis will entail (Fiore et al., 2019). These unrealistic expectations gradually adjust as participants progress in their programs, which is relevant since realistic expectations are correlated with satisfaction and persistence (Naylor et al., 2018).

The online doctorate is a non-linear, arduous journey. Studying online requires more self-discipline, commitment, and focus than studying in a traditional format (Erichsen et al., 2014). More than half the participants in Brown (2017) and Jameson and Torres (2019) contemplated dropping out at some point. Without going that far, taking a break is very frequent. In Berg (2016), almost 70% of the participants took a break due to financial constraints, family responsibilities, or academic issues. Students find the most challenging aspects of their PhD journeys are feelings of loneliness or abandonment and having to fend for themselves; the difficulty in attending to the demands of the program while meeting job and family obligations; and the debt burden and general financial struggles.

Despite the hardships, most students are satisfied with their online PhD programs. In Naylor et al. (2018), 80% of learners described a positive experience, regardless of their demographic characteristics. Meanwhile, satisfaction was strongly linked to effective supervision in Erichsen et al. (2014), and it grew as the student persisted and advanced with the program in Ivankova and Stick (2007). One of Halter et al.’s (2006) participants put words to this generalized perception:

I did feel that isolation sitting behind my computer. It was a small price to pay for having an opportunity to sit in a course on a winter night and be in my pajamas and coffee with me. The good outweighs the bad. (p. 102)

The supervisory relationship is the most important factor (Fiore et al., 2019; Naylor et al., 2018) affecting students’ satisfaction, persistence, and successful completion of the doctorate. It is pivotal in facilitating the transition from the coursework stage of the PhD journey to the often perceived as daunting dissertation stage, where more independent research and writing are required. This central role of the advisor in facilitating students’ advancement works also in the opposite direction: a poor relationship with the advisor is a direct path toward lack of motivation (Jameson & Torres, 2019) and disaffection (Naylor et al., 2018), and consequently lies behind many decisions to drop out (Fiore et al., 2019; Jameson & Torres, 2019).

Online delivery introduces some additional challenges to PhD supervision. For instance, the initial matching of the student with the supervisor is crucial but often challenging (Lee, 2020). Communication can also be hampered by distance and should be facilitated proactively by advisors (Kumar et al., 2013). On the students’ side, difficulties lie in acting on an advisor’s feedback and developing a “tough skin” to be able to cope with the constant criticism constructively (Kumar et al., 2013). Overall, Kumar et al.’s participants valued mentors that provide structure, clear expectations, and deadlines; timely and specific feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the work done; and gentle criticism and positive reinforcement, all of which acted as motivators.

On the other hand, students highly appreciate having a community of peers (Andrew, 2012) and think it contributes decisively to their adjustment and success in the program (Lee, 2020; Studebaker & Curtis, 2021). Having a strong community is closely related to engagement and thus persistence (Byrd, 2016), and it is a protective factor when intentions to drop out arise. Reliance on peers helps students alleviate isolation and develop coping mechanisms to face challenges during their doctoral studies (Halter et al., 2006). In this sense, having a cohort with which students experience the same milestones at the same time gives them a sense of security and consistency, in what they describe as a “family-like” sentiment (Byrd, 2016; Studebaker & Curtis, 2021). In-person contact at some point during the PhD program, in the form of initial residencies or sporadic face-to-face meetings, markedly helps build this togetherness, igniting community-building (Berg, 2016; Byrd, 2016; Halter et al., 2006).

Finally, alongside advisors and peers, online PhD students rely on other sources of support such as significant others, family, friends, or co-workers to help them push ahead (Byrd, 2016). They receive assistance from these persons in areas such as childcare, running errands, or addressing financial issues. However, despite this support, their persistent feeling is one of not being able to meet their whole range of responsibilities (Brown, 2017).

Personal factors such as motivation, emotions, skills, and personality impact students’ achievement in a program, dynamically interacting with the abovementioned relational factors. Intrinsic motivation in the form of self-direction, passion, and drive has a remarkable effect on students’ persistence across studies, even outweighing external factors such as the characteristics of the program, the quality of the advisor’s performance, or the students’ work/life balance (Fiore et al., 2019; Ivankova & Stick, 2007). Emotion wise, Kennedy and Gray (2016) found that students felt the most positive about personal sense of progression and belonging to the community, while the absence of embodied communication, inflexible deadlines, and study “invading” nights and weekends elicited the most negative affects. In addition, some personalities, such as independent, introverted, or goal-oriented people, seem to better adapt to online PhD work (Halter et al., 2006).

The stage students are in the program is relevant. Studies differentiate between the course stage and the dissertation stage of the PhD program. In the former, the student takes compulsory courses, while the latter progressively entails actual independent research and writing. Figure 2 summarizes some trends, derived from our analysis, on the modulating effect of the PhD stages on personal variables.

Figure 2

Observed Trends in the Online Doctoral Journey

Initially, students are highly motivated (Ivankova & Stick, 2007) but have an inaccurate perception of what a distance PhD program implies (Jameson & Torres, 2019; Lee, 2020). During the 1st year, unadjusted expectations confront reality, while motivation is based on an external locus of control. Around the end of the 1st year or at the beginning of the 2nd year, expectations tend to adjust as students get to know the reality of an online doctorate. They are entering the dissertation stage. This transition is often lived as a time of shock and crisis (Fiore et al., 2019; Jameson & Torres, 2019; Lee, 2020) since the harshness of the program becomes evident and self-competence is not yet fully settled. In this period, students are particularly vulnerable to frustration if some external factors, particularly the supervisory relationship, fail to motivate them (Fiore et al., 2019). Progressively, while advancing in the program, students start to gain more confidence in their ability to carry out independent research (Jameson & Torres, 2019), and thus, intrinsic motivation grows (Ivankova & Stick, 2007). This higher level of perceived competence is accompanied by the development of a scholarly identity and the confidence in being able to successfully complete the PhD program (Natal et al., 2020).

The purpose of this systematic review was to summarize current knowledge about the experiences and perceptions of online PhD students along their academic journey. To follow, we outline the main arguments derived from this work.

First, online doctoral students are generally satisfied with their programs, yet feelings of isolation, the study/life balance, and financial constraints are challenging. We found that students’ satisfaction with their programs was high across disciplines. Previous studies provided conflicting evidence in this regard, with some finding, as in our case, no difference in students’ satisfaction among disciplines (Barnes & Randall, 2012) and others (Nettles & Millett, 2006) lower satisfaction in the social sciences than in natural sciences. Unsurprisingly, the most predictive factor related to satisfaction was the number of semesters students have been enrolled in the program. This can be related to evidence indicating that as students advance in a program, so do their perceived skills in conducting independent research, adjusted expectations on what a PhD program entails, and intrinsic motivation to pursue their goals. Satisfaction is also closely related to online doctorates’ profiles. As non-traditional students, pursuing an online degree allows them to balance their studies with personal responsibilities and better manage chronic time scarcity.

Nonetheless, taking a break for one or more semesters and considering leaving the program was a very frequent occurrence. There are several reasons for this circumstance. Loneliness, difficulties with managing study with work and family responsibilities, and financial issues all take a toll on online doctoral candidates. The studies reviewed indicated students were often not prepared for the isolation they would go through during a PhD program. Even though loneliness is commonly referred to in the literature as a hampering factor in the general doctoral population (Rigler et al., 2017), the distance modality seems to aggravate this predicament. In this regard, students experienced ambivalent feelings: they chose the online modality for its flexibility and “anytime, anywhere” features, but eventually found themselves craving physical proximity. Ultimately, they felt it was extremely helpful for programs to have some kind of face-to-face interaction, which helped ignite a sense of community later in the program. Indeed, Conrad (2005) noted an “enormous surge in connectedness and satisfaction with the program design” (p. 9) in online doctoral students who were able to meet face-to-face at least once.

Previous research showed that while flexibility provides educational opportunities, it also demands more self-regulatory skills on the students’ side (Xavier & Meneses, 2021). Our results point to an equivalent concern regarding study/life balance. The same flexibility that allows adult learners to pursue an online PhD program is to blame for blurred borders between their academic and personal lives, and the sensation that the latter progressively shrinks. Relatedly, Akojie et al. (2019) highlighted how this feeling of being chronically time-deprived is particularly pervasive among online doctoral students. This is relevant since Evans et al. (2018) found that perceived poor study/life balance is a risk factor for depression and anxiety during a PhD program. Financial hurdles are another factor jeopardizing students’ progress. Many online doctorates do not give an accurate picture of the actual costs of a PhD program, even more so because they usually prolong their studies, which adds to mounting costs and uncertainty. Rigler et al. (2017) linked ongoing enrolment with current costs, opportunity costs, and the expected benefits of attaining a PhD degree. Similarly, the studies reviewed pointed at students carefully assessing the worth of earning a doctorate considering its trade-offs. Minority students and those living in low-income countries were particularly affected by financial concerns. All the above-mentioned challenges might be causally connected to the mental health vulnerabilities detected in PhD candidates, which greatly exceed those of the general population (“Being a PhD Student Shouldn’t Be Bad for Your Health,” 2019; Evans et al., 2018).

The second argument derived from this study concerns two common factors affecting success and satisfaction: the supervisory relationship determines the quality of students’ academic experience, while a strong sense of community helps them to get ahead.

Supervision was the most frequent domain covered in the studies reviewed and a central factor in students’ testimonies when it comes to not only successfully completing their online PhD degree but also facilitating future career prospects. This protagonist role of the supervisor in the PhD student’s academic life has been extensively examined in the literature, from the classic work of Tinto (1975) to recent reviews on doctoral students (Madan, 2021; Sverdlik et al., 2018). Golde (2000) described how behind many attrition stories lies a bad relationship with the supervisor. This is also true in our results, where online students think an initial match with the supervisor, in their first year, is crucial but often challenging. Golde also stated that poor supervision has often more to do with indifference than downright neglect or abuse. In this respect, among the dissatisfied doctorates in the studies reviewed, many felt stuck with unsupportive supervisors who did not seem to care, and ended up having to resort to internal motivators like passion or drive to cope and persist in their studies. Gray and Crosta (2019) remarked that the qualities of a good supervisor are independent of the delivery modality, but also that counseling students online introduced additional challenges to interaction. Doctoral students in the studies also felt building satisfactory relationships and rapport was harder in the absence of face-to-face interaction. For this reason, they preferred a supervisor who takes a proactive stance on accompaniment but who is also flexible enough to take into account that most students are working adults with multiple responsibilities.

While the supervisor is a central figure in facilitating students’ progress, having a community of supporting peers is what helps online doctorates cope when the former or other aspects of the PhD program do not go as expected. Sakurai et al. (2012) observed that while there is often ambivalence regarding the supervisor’s impact on their engagement and performance when students happen to have a community of peers, it has almost always a positive net effect. Our findings support this reflection. Separately, previous research highlighted the importance of the cohort-based program structure (Akojie et al., 2019), and how not being in a cohort program is detrimental to students’ socialization, resulting in increased perceived isolation (Spurlock & Cunningham, 2016). In our findings, the cohort-based community was progressively seen by online doctoral students as an academic “family.” It helped them overcome academic difficulties, fight loneliness, and, above all, keep motivated. Peers shared knowledge in an informal way and helped each other emotionally. In this regard, we should bear in mind that community-oriented students perform better than those working individually (Spurlock & Cunningham, 2016).

The third main argument concerns how personal factors such as expectations, motivation, emotions, and skills modulate students’ fit throughout a PhD program. Past research (Sakurai et al., 2017) noted that engagement and persistence in the PhD journey are influenced by personal aspects such as motivation, self-regulatory strategies, and skills. Yet these factors are, in turn, dynamic and evolve as the individual progresses from the initial stage of a PhD program to a more advanced one in which conducting research independently and writing the thesis take centre stage. In this sense, we identified several trends in this review. Online doctoral students begin the PhD journey highly motivated but with unrealistic expectations of what lies ahead and feeling insecure about their writing skills. As they begin facing the reality of the doctorate, expectations adjust, but this period around the end of the first year can be one of crisis. Our findings reflect both Sakurai et al.’s (2012) remarking that motivation needs to be continuously nurtured, and Sverdlik et al.’s (2018) stressing that lack thereof is, for many, the main reason for dropping out, and thus the need for institutional support in times of crisis. For those who advance in their programs, however, the perception of increased ability to do research is accompanied by a developing “scholarly” identity—even though many, as working professionals, do not aim towards an academic path—with drive and inner motivation following.

We reviewed the available literature regarding online doctoral experience, and most of it came from Western, English-speaking countries and the fields of education and psychology. A more diverse set of studies encompassing populations from other geographical areas, ethnicities, genders, and scientific fields would certainly add nuance and complexity to our findings. In this regard, it would be especially instructive to use an intersectional approach that examines how the interaction of race, class, and gender influences the lived experiences of online PhD students. In this review, we have stressed the online feature of the PhD experience. Still, reviewing part-timers’ specific struggles (Gardner & Gopaul, 2012; Gatrell, 2020) might widen understanding of this doctoral population. Although there is partial overlap with full-timers in terms of challenges encountered, part-timers are a particularly understudied, precarious, and peripheral doctoral population. Likewise, we have indicated some crucial differences between the online and face-to-face doctoral experience. However, not being the focus of our work, further research on this topic in terms of its impact on persistence and students’ well-being would be valuable. Finally, it would be enlightening to research the voices of those doctoral candidates who left academia. The studies reviewed remark that enrolled students and those ahead in their programs are the most satisfied, yet we lacked hearing from those who dropped out.

Pursuing an online doctorate is more isolating than face to face and introduces additional challenges to the supervision process and students’ study/work/life balance. This review showed that relational factors, either as part of a supervisory relationship or in a community of peers, were crucial in assisting online doctoral students to persist in their studies and avoid intentions to drop out. Accordingly, institutions can improve the online PhD experience by strengthening cohort-based structures, providing some type of in-person opportunity throughout the programs to boost socialization, and facilitating awareness and training among supervisors with regards to adult, working professional students’ particular needs in terms of flexibility and accompaniment.

This work was supported by doctoral grants from the Government of Catalonia (2021-FISDU-00310) and the Open University of Catalonia (2019/00003/001/006/006).

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Akojie, P., Entrekin, F., Bacon, D., & Kanai, T. (2019). Qualitative meta-data analysis: Perceptions and experiences of online doctoral students. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 3(1), 117-135. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/5814

Andrew, M. (2012). Supervising doctorates at a distance: Three trans‐Tasman stories. Quality Assurance in Education, 20(1), 42-53. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881211198239

Barnes, B. J., & Randall, J. (2012). Doctoral student satisfaction: An examination of disciplinary, enrollment, and institutional differences. Research in Higher Education, 53(1), 47-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9225-4

Baltes, B., & Brown, M. (2018). Impact of additional early feedback on doctoral capstone proposal approval. International Journal of Online Graduate Education, 1(2), 2-11. https://ijoge.org/index.php/IJOGE/article/view/21

Being a PhD student shouldn’t be bad for your health [Editorial]. (2019). Nature, 569(7756), 307. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01492-0

Berg, G. A. (2016). The dissertation process and mentor relationships for African American and Latina/o students in an online program. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(4), 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1227191

Brown, C. G. (2017). The persistence and attrition of online learners. School Leadership Review, 12(1), 47-58. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1277006.pdf

Burrus, S. W. M., Fiore, T. D., Shaw, M. E., & Stein, I. F. (2019). Predictors of online doctoral student success: A quantitative study. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 22(4), 61-66. https://www.westga.edu/~distance/dla/pdf/2019-dla-proceedings.pdf#page=61

Byrd, J. (2016). Understanding the online doctoral learning experience: Factors that contribute to students’ sense of community. The Journal of Educators Online, 13(2), 102-135. https://doi.org/10.9743/JEO.2016.2.3

Castelló, M., Pardo, M., Sala-Bubaré, A., & Suñe-Soler, N. (2017). Why do students consider dropping out of doctoral degrees? Institutional and personal factors. Higher Education, 74(6), 1053-1068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0106-9

Conrad, D. (2005). Building and maintaining community in cohort-based online learning. International Journal of E-Learning & Distance Education, 20(1), 1-20. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ807822.pdf

Erichsen, E. A., Bolliger, D. U., & Halupa, C. (2014). Student satisfaction with graduate supervision in doctoral programs primarily delivered in distance education settings. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 321-338. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709496

Evans, T. M., Bira, L., Gastelum, J. B., Weiss, L. T., & Vanderford, N. L. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36(3), 282-284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Fiore, T. D., Heitner, K. L., & Shaw, M. (2019). Academic advising and online doctoral student persistence from coursework to independent research. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 22(3). https://ojdla.com/archive/fall223/fiore_heitner_shaw223.pdf

Gardner, S. K., & Gopaul, B. (2012). The part-time doctoral student experience. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 63-76.

Gatrell, C. (2002). Mission impossible: Doing a part time PhD, (or getting 200% out of 20%) - is it really worth it? In N. Greenfield (Ed.), How I got my postgraduate degree part time (pp. 85-95). Lancaster University.

Golde, C. M. (2000). Should I stay or should I go? Student descriptions of the doctoral attrition process. The Review of Higher Education, 23(2), 199-227. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2000.0004

Gough, D., & Thomas, J. (2016). Systematic reviews of research in education: Aims, myths and multiple methods. Review of Education, 4(1), 84-102. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3068

Gray, M. A., & Crosta, L. (2019). New perspectives in online doctoral supervision: A systematic literature review. Studies in Continuing Education, 41(2), 173-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1532405

Halter, M. J., Kleiner, C., & Hess, R. F. (2006). The experience of nursing students in an online doctoral program in nursing: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(1), 99-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.001

Ivankova, N. V., & Stick, S. L. (2007). Students’ persistence in a distributed doctoral program in educational leadership in higher education: A mixed-methods study. Research in Higher Education, 48(1), 93-135. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-006-9025-4

Jameson, C., & Torres, K. (2019). Fostering motivation when virtually mentoring online doctoral students. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.5590/JERAP.2019.09.1.23

Kelley, M. J. M., & Salisbury-Glennon, J. D. (2016). The role of self-regulation in doctoral students’ status of all but dissertation (ABD). Innovative Higher Education, 41(1), 87-100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-015-9336-5

Kennedy, E., & Gray, M. (2016). ‘You’re facing that machine but there’s a human being behind it’: Students’ affective experiences on an online doctoral programme. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 24(3), 417-429. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2016.1175498

Kumar, S., Johnson, M., & Hardemon, T. (2013). Dissertations at a distance: Students’ perceptions of online mentoring in a doctoral program. Journal of Distance Education, 27(1), 1-11. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1426932680

Lee, K. (2020). A phenomenological exploration of the student experience of online PhD studies. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 15, 575-593. https://doi.org/10.28945/4645

Litalien, D., & Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 218-231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.004

Lovitts, B. E. (2001). Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Madan, C. R. (2021). A brief primer on the PhD supervision relationship. European Journal of Neuroscience, 54(4), 5229-5234. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15396

Madhlangobe, L., Chikasha, J., Mafa, O., & Kurasha, P. (2014). Persistence, perseverance, and success: A case study to describe motivational factors that encourage Zimbabwe Open University students to enroll, persist, and graduate with master’s and doctorate credentials. SAGE Open, 4(3), https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014544291

Marston, D., Gopaul, M., & Kenney, J. (2019). Issues to consider for online doctoral candidates utilizing meta-analysis for dissertations. International Journal of Online Graduate Education, 2(1), 2-16. https://ijoge.org/index.php/IJOGE/article/view/30

Natal, M., Jimenez, R., & Htway, Z. (2020). Lived experiences of Asian and Latinx online doctoral students. American Journal of Distance Education, 35(2), 87-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1793642

Naylor, R., Chakravarti, S., & Baik, C. (2018). Expectations and experiences of off-campus PhD students in Australia. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(4), 524-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1301405

Nettles, M. T., & Millett, C. M. (2006). Three magic letters: Getting to PhD. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Offerman, M. (2011). Profile of the nontraditional doctoral degree student. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2011(129), 21-30. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.397

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), Article 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., ... McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372(160). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Rigler, K. L., Bowlin, L. K., Sweat, K., Watts, S., & Throne, R. (2017, March 21-23). Agency, socialization, and support: A critical review of doctoral student attrition [Paper presentation]. 3rd International Conference on Doctoral Education, University of Central Florida, Orlando, United States. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED580853.pdf

Sakurai, Y., Pyhältö, K., & Lindblom‐Ylänne, S. (2012). Factors affecting international doctoral students’ academic engagement, satisfaction with their studies, and dropping out. International Journal for Researcher Development, 3(2), 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1108/17597511311316964

Sakurai, Y., Vekkaila, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2017). More or less engaged in doctoral studies? Domestic and international students’ satisfaction and motivation for doctoral studies in Finland. Research in Comparative and International Education, 12(2), 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499917711543

Spurlock, C. & Cunningham, M. (2016). Socialization and retention of part-time doctoral students: A review of ten years of literature. In S. Whalen (Ed.), Proceedings of the 12th National Symposium on Student Retention, Norfolk, Virginia (pp. 372-383). University of Oklahoma. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Socialization-and-Retention-of-Part-Time-Doctoral-A-Spurlock/d6cdfeb80f48db2b01b18f942474e3909b4e332b

Studebaker, B., & Curtis, H. (2021). Building community in an online doctoral program. Christian Higher Education, 20(1-2), 15-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2020.1852133

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N., McAlpine, L., & Hubbard, K. (2018). The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students’ completion, achievement, and well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 361-388. https://doi.org/10.28945/4113

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), Article 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89-125. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3102/00346543045001089

Vossensteyn, H., Kottmann, A., Jongbloed, B. W. A., Kaiser, F., Cremonini, L., Stensaker, B., Hovdhaugen, E., & Wollscheid, S. (2015). Dropout and completion in higher education in Europe: Main report. European Union. https://doi.org/10.2766/826962

Xavier, M., & Meneses, J. (2021). The tensions between student dropout and flexibility in learning design: The voices of professors in open online higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 22(4), 72-88. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v23i1.5652

The Online PhD

Experience: A Qualitative Systematic Review by Efrem Melian, Jose

Israel Reyes, and Julio Meneses is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License.