Volume 24, Number 2

Kelly Arispe, Ph.D. and Amber Hoye, M.E.T.

Boise State University

Open educational resources (OER) are disproportionately created and/or accessed by institutions of higher education as compared to K-12 even though teachers confront the challenge of outdated teaching materials or, worse, an increasing trend by school districts to discontinue textbook adoption altogether. In this paper, we describe a sustainable and innovative example of OER-enabled pedagogy (OEP) that partners teachers and students across institutional boundaries to address these problems. The Pathways Project (PP) is a higher education and K-12 community of 350 world-language teachers, students, and staff that engage in the 5Rs (retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute) of OEP with a repository of more than 800 OER ancillary activities that support standards-based pedagogy for 10 world languages and cultures. The PP is innovative because it fosters renewable assignments for the entire disciplinary ecosystem unlike most OEP studies that discuss renewable assignments limited to a single course. Teacher education is one of the best places to engage OEP because teachers are trained to personalize and contextualize OER materials for their local classroom needs. In so doing, the PP community receives timely discipline-specific professional development that is in high demand, especially in rural communities where teachers are isolated. Higher education-K-12 OEP partnerships are rare, and yet teacher education programs exist in most universities and can be a logical place to start. This paper provides concrete examples and practical steps that are transferable to other disciplines looking to engage in similar types of OER-OEP collaboration and community engagement.

Keywords: OEP, renewable assignments, teacher education, K-12, higher education

One of the challenges facing U.S. institutions of higher education is collaborating with external communities to solve complex problems with outcomes that are mutually beneficial (Allan, 2021; Gimbel 2018). This is especially the case for institutions in rural states of the U.S. where the urban-rural divide is increasing, and communities may be suspicious of the value higher education has to offer (Parker, 2019). Furthermore, K-12 public institutions, especially those in rural communities, have a serious resource problem (Tomlinson, 2020). School districts are increasingly discontinuing textbook adoption while changing curricula to norm to updated standards. As a result, teachers can be left with the burden of creating their own materials with little time and training to do this well.

Open educational resources (OER) can be a bridge for community outreach and K-16i engagement through strategic teacher education. The Pathways Project (PP; https://www.boisestate.edu/pathwaysproject/) is an open educational resource (OER) that was created in 2018 to address these challenges and to engage K-12 and higher education educators, undergraduate students, and academic staff in a partnership fundamentally rooted in OER-enabled pedagogy (OEP). OEP is a constructivist process characterized by the 5Rs (retain, reuse, revise, remix, and redistribute) whereby using and creating OER materials is at the nexus of discipline-specific professional development that results in quality teaching materials in high demand.

Unfortunately, across K-12 institutions in the United States, two-thirds of teachers have no awareness of OER (Seaman & Seaman, 2022). This contrasts with growth in OER awareness in higher education institutions that report a 20% increase in awareness over the last five years (57% in 2022 compared to 37% in 2017). It is safe to assume that OEP, which is active engagement in the process, not solely awareness of OER, is even lower. Teacher education is a logical place to address these challenges, yet a recent survey revealed only 1% of teacher education courses use OER and only two survey respondents reported offering student teachers the opportunity to participate in the OER creation process in their courses (Van Allen & Katz, 2020).

This disparity no doubt is responsive to the paucity of research and innovative praxis focused on teacher education and OEP in general. Recent scholarship has focused on OEP and renewable assignments as a learning outcome tied to a specific course in teacher education programs (Van Allen & Katz, 2019). Renewable assignments are student work that is created for a greater audience and purpose than a singular course. For example, they can be integrated into or remixed in subsequent semesters for the benefit of future students.

The PP is an example of OEP that provides a nuanced approach to renewable assignments and OEP in general, primarily with regards to scope. The process of OEP leads to renewable materials that are openly shared with a larger, global community of world-language educators. The PP is integrated into several higher education courses, undergraduate internship opportunities, and in-service teacher development workshops and training. As a result, renewable assignments take on a whole new meaning because they are not limited to a specific course topic or even a core curriculum. This is largely because the PP OER is a repository of over 800 face-to-face and online ancillary classroom activities that support standards-based pedagogy for 10 world languages and cultures. Each activity follows a standard design protocol based on best practices in world-language teaching and aligns with state and national standards. Furthermore, every activity contains all materials needed for classroom implementation, making the process of revising or remixing activities more practical and accessible so that teachers can adapt materials to meet the needs of their specific learners.

This paper provides important contributions to contexts where there is little to no OEP scholarship. There is an overwhelmingly disproportionate representation of OEP in STEM or business and little to none in the humanities. For example, a recent meta-analysis on K-12 OER research studies found only one instance of humanities content included (Blomgren & McPherson, 2018). Furthermore, most research is focused on contexts within higher education that measure the impact of OER textbooks rather than examining the effectiveness of ancillary materials even though ancillary materials are more highly regarded by K-12 teachers for their customizability (Blomgren, 2018). Most importantly, the PP bridges the gap between institutions of higher education and K-12 and, in this way, provides insights applicable to any discipline and for every level of education.

OEP is a process rooted in constructivist principles of learning whereby users learn by doing and for a purpose (Van Allen & Katz, 2019; Wiley et al., 2017; Wolfenden & Adinolfi, 2019). OEP products contribute to a real-world purpose; for example, the materials created might respond to an authentic need in the learning community and be accessible to an audience beyond the immediate context. At the core, OEP should produce renewable resources that contribute to a repository for future use. OEP is most often described in the literature involving undergraduate student learners as the users and course materials as the content created; students work on renewable assignments that are then integrated into coursework for future semesters. Students learn how to openly license and share their materials which is the evidence of the learning outcomes.

Teachers, like students, can also participate in OEP and, in so doing, participate in transformative pedagogical practices where continuous learning and professional development are also outcomes. OEP is digital scholarship and fundamentally different from teaching with copyrighted materials because it requires teachers “to be consciously engaged in either building upon work previously done by another or to construct a new public entity that explicitly provides other learners permission to publicly transform and adapt it” (Wiley et al., 2017, p. 136). It is this level of conscientious engagement that differs from more traditional professional development experiences. Teachers take ownership of their investment because they recognize that they both reap the benefits of their contributions and that they are supporting future teachers by sharing their work for future use.

OEP can also respond to important resource challenges facing K-12 landscapes. Textbook adoptions are expensive, and professional development workshops don’t always address critical content needs for teachers of specific disciplines. Furthermore, textbooks are often lacking or lag when it comes to diverse representation, whether it be through the images selected or the perspectives that are presented. This is especially concerning for world-language teachers who are trying to facilitate and foster intercultural competence as one of the main learning objectives. Finally, textbooks are costly, and K-12 school districts have increasingly chosen either not to acquire a newer edition (further outdating and complicating the diversity problem) or to do away with textbooks altogether. This trend is disproportionately impacting rural communities and especially in disciplines like world languages that tend to offer fewer courses and may have one or two teachers for the entire district. Considering the recent COVID-19 pandemic, Van Allen and Katz (2020) remarked that “now is the opportune time to introduce educators to OER and advocate for its use over commercially published materials that are being made freely available during the crisis” (p. 215). What is more, teachers don’t do this in isolation; rather, they collaborate with one another for the purpose of long-term renewable use.

One of the challenges facing teacher educators wishing to use OEP as a transformational pedagogical experience is to set clear expectations about the nature of the OEP process. Most teachers are initially drawn to OER because it can save time by not having to create materials from scratch. While this is certainly true, the most compelling argument for engaging in OEP is that it is content-specific professional development rooted in learning by doing and socially constructed (Wolfenden & Adinolfi, 2019).

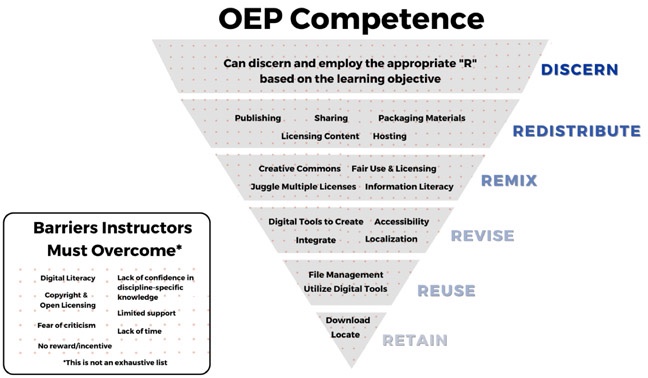

OEP is a process that moves the teacher from passive “taker” to active “engager” whereby the teacher can discern which “R” to employ based on the OER material(s) and the learning objective at hand. Unlike scouring the Internet for a single stand-alone material, OER materials are designed to be modified and become more pedagogically useful when adapted, not just adopted. Teachers negotiate their individual needs through the ways they localize the OER materials for their learners and according to the tasks/learning objectives. For example, they can infuse their own creative and subject-matter expertise to transform materials into something that is more contextualized and efficacious for their personal teaching environment. At its most profound level, the teacher is participating in collective practices that contribute to the potential for continued localization by future teachers engaging in OEP. However, to do so requires a certain level of OEP competence. As depicted in Figure 1, we characterize the 5 Rs through an inverted pyramid whereby the skills practiced at the upper echelon of the pyramid encompass the skills below. For example, a teacher wanting to remix an OER material will first need to retain, reuse, and revise the material so that she can remix it with other materials. Although the skills differ and grow in complexity with each of the R competencies, teachers may encounter the barriers listed at any point or multiple points along the way. The goal in OEP competence is not necessarily to have teachers revise and remix every OER material. Rather, it is for the teacher to know when to use which R for the right pedagogical purpose. Therefore, OEP must be firstly rooted in pedagogical understanding in the discipline. This foundation is the filter by which the teacher can decipher how to operationalize OEP.

Figure 1

Teacher OER Competence: The 5 Rs of OEP

As described above, the potential outcomes that spring from OEP should never be reduced solely to their products (OER materials). Teacher educators can help dispel this myth and prepare teachers to understand the OEP process with realistic expectations. At the same time, at a system level, higher education institutions should also consider how they make this work more visible and accessible by providing academic credit through online, informal OER/OEP coursework. A recent report on micro-credentialing by UNESCO chairs (see McGreal et al., 2022) details the affordances and barriers to consider in making this work count and to elevate more equitable professional learning opportunities for all teachers, regardless of place and time, online. In the PP context specifically, K-12 teachers engaging in the 2022-2023 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant activities earned one credit of academic professional development from the host institution. Furthermore, the directors awarded badges (https://badgr.com/public/issuers/JWCzlrrZTC6lO7UOjxsIJQ/badges) through Badgr (https://badgr.com/) that highlighted the course learning outcomes and provided evidence of OEP skills developed in the process.

While professional development and institutional support through course credit and badging are two ways to incentivize participation, the greatest barrier facing teachers engaging in OEP is firstly to locate the OER materials themselves and to be guided in a thriving OEP environment. In the section that follows, we turn to the PP, which serves as a transferable example and a systematic approach to building content-specific ancillary OER materials for a sustainable OEP community of practiceii that spans institutional boundaries.

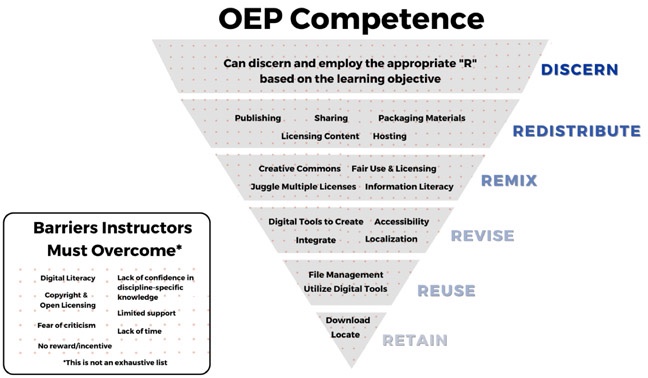

The genesis of the PP began in 2014 in a language resource center (LRC) where undergraduate students participate in weekly conversation sessions lasting 30 minutes. These sessions are integrated into lower-division coursework and are designed to engage students in spontaneous conversation, an aspect of language learning that is often most challenging for teachers to facilitateiii. Figure 2 provides descriptions of three sample activities.

Figure 2

Pathways Project Sample Ancillary Activity Descriptions

Note. Activity links: La subasta/The Auction (https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/50436-spanish-level-1-activity-08-la-subasta-the-auction/view); Salutations et présentations/Greetings and Introductions (Junior High Version; https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/62339-french-level-1-activity-02-salutations-et-pr%C3%A9senta/view); and El mundo del trabajo/The World of Work (Online Activity; https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/74468). Images from https://pexels.com.

Most lower-division undergraduate courses have some overlap with K-12 content. This is especially the case for language learning whereby novice and intermediate level language courses may be represented at all institutional levels, K-16. Moreover, many of the content-specific pedagogical challenges we were observing in our own language department, for example, new standards, lack of resources, costly textbook adoptions, lack of time, and so forth, were similar to the challenges being voiced in the K-12 world-language communities in our region.

By 2018, we were observing consistent positive language learning gains and improved student engagement because of the LRC conversation activities in our language program. As a result, we launched the PP as an OER repository to support a broader community of teachers who wanted to help learners improve their ability to converse but were lacking the resources and/or pedagogical training to do so. The activities that were originally created for our undergraduate LRC conversation sessions became the foundational PP activities that have been revised, remixed, and redistributed. As is shown in figures 3 and 4, each activity follows a similar scope and sequence adhering to best pedagogical practices, and provides a consistent template that facilitators can use.

Figure 3

The Foundational Structure of Pathways Project Activities

Note. From Exercise icon [Photograph] by katemangostar by freepik.com. Images from https://pexels.com.

Figure 4

The Scope and Sequence of Every Pathways Project Activity

Today, the PP hosts more than 800 face-to-face and online conversation activities for 10 world languages at the K-16 levels. Over 350 undergraduate students and teachers (K-12 and higher education) have been actively involved in materials creation, and the PP has a following of over 1,000 subscribers who receive monthly newsletters, attend webinars and workshops, and/or retain and reuse materials.

The PP aspires to continue supporting undergraduate learning within the higher education institution where it is housed while simultaneously augmenting and strengthening community engagement with K-12 teachers in both urban and rural school districts. The PP achieves these goals by focusing on growing/producing high quality, customizable teaching materials and providing accessible professional development in the discipline. The PP OER repository is categorized by subject and level and all materials are tagged with keywords to make them easier to find. Following a consistent template (Figure 4) across activities helps to reduce the time spent looking for an activity. Rather, users can focus their efforts on revising and remixing the activities through the embedded remix tool provided by OER Commons. Frequent professional development, in the form of tutorials, workshops, and webinars, develops and strengthens OEP teacher confidence to redistribute revised and remixed activities (i.e., renewable resources) for the larger PP community. These materials and professional development opportunities are constantly growing and improving, thanks to the PP team that brings together students, staff, and teachers, and is described in detail in the following section.

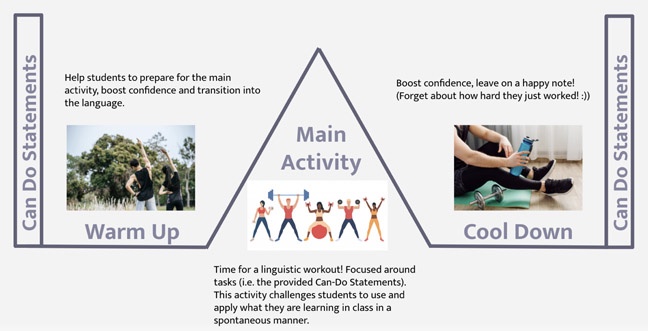

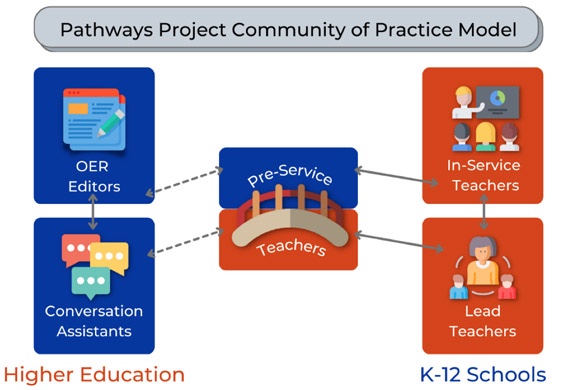

Undergraduate students play a central role in the creation and dissemination of PP activities. One of the greatest benefits for undergraduate student involvement in OER and OEP is hands-on career-readiness and interdisciplinary collaboration. This is especially the case for academic programs in the humanities where students can showcase their competencies in their major/minor by working on a project that directly impacts local communities. In the early stages of the PP, we recognized the importance of student involvement and identified distinct student profiles to assign different roles and responsibilities for ways students could help develop, refine, publish, and implement PP OER. As depicted in Figure 5, we created three distinct student creator roles to leverage students’ academic experiences and interests: (a) OER editors, (b) conversation assistants, and (c) pre-service teachers. To sustainably recruit and retain undergraduate participation for these positions, we use two established pathways at the university: work study and internship for credit. In addition, we offer a limited number of paid hourly positions that we fund through a small fee attached to lower-division courses that have a conversation lab component.

Figure 5

Pathways Project Student Profiles and Roles

Note. Images from Chat icon by Vectors Market via freepik.com, Bridge icon by Free Pik via freepik.com, Notepad icon by itim201 via freepik.com.

Activity development begins with conversation assistants who are content providers and stem from both language majors and minors and pre-service teachers. This group also includes native, heritage, and advanced speakers who are not presently language majors or minors. They use their knowledge of the target language and culture to develop ancillary materials and prepare a complete, highly customizable activity that contains a facilitation guide for instructors, a slide deck, and additional instructional materials depending on the activity. Once created, conversation assistants facilitate the activities with small student conversation groups and report back to OER editors about any changes that may need to be made to enhance the instructional experience.

Students from all three profiles, as shown in Figure 5, may work as an OER editor. These students proofread and polish activities, test out multimedia materials, and ensure consistent instructional design. OER editors are responsible for openly licensing and publishing the activities designed by conversation assistants through OER Commons and Pressbooks. This team of students may also assist in-service teachersiv wishing to publish materials they have created. In doing so, they help address barriers depicted in Figure 1 such as lack of time and skills, confidence in the quality of one’s materials, and knowledge about copyright and licensing (Bates et al., 2007; Rolfe, 2012; Windle et al., 2010).

Pre-service teachers are secondary education majors completing both language and teacher education courses and often work in all three creator roles, starting first as a conversation assistant or OER editor during their first and second years. In their third year, they take two methodology/pedagogy courses where the PP is integrated into course assignments. For example, the professor uses several PP OER ancillary activities as a model for facilitating standards-based practices to foster student engagement. In addition, students are taught how to retain, reuse, and revise the PP activities as formative exercises in both courses. This gives them opportunities to identify, select, and appraise how an activity might align with a typical K-12 curriculum. Finally, they complete a summative assessment where they design a unit plan that integrates a revised PP activity. Thus, by the end of their third year, all pre-service teachers have engaged in OEP and can employ their newfound competence to their field experiences.

Unique to this role, pre-service teachers dedicate most of their fourth and final year to their field experiences in local schools. Here they are encouraged to showcase PP activities to their in-service mentor teachers and to practice implementing their revised activities with students. This is an invaluable way both pre- and in-service teachers exchange expertise; pre-service teachers model to in-service teachers the process for locating and integrating PP activities in any given unit and in-service teachers provide expert knowledge on how to implement the activities in the classroom and evaluate the efficacy of the PP activities in practice. Thus, undergraduate students play a vital role in bridging OEP opportunities between higher education and K-12 institutions by generating PP OER activities that are then customized by teachers for local purposes. Figure 6 shows the different members of the PP team who support the OEP community of practice.

Figure 6

The Pathways Project Community of Practice: Bridging Institutional Boundaries With OER

Note. Images from Chat icon by Vectors Market via freepik.com, Bridge icon by Free Pik via freepik.com, Notepad icon by itim201 via freepik.com, Teach icon by Nikita Golubev via freepik.com, and Communication icon by Free pik via freepik.com.

One of the greatest challenges when engaging in OEP across institutional boundaries is to find an approach that is sustainable and equitable. There are many disciplines in higher education that have teacher education programs. One of the defining features of these programs is that pre-service teachers are mentored by in-service teachers through field experiences in secondary schools over several semesters towards the end of the program. However, the number of pre- and in-service teachers is relatively small, especially for world languages. Thus, it was imperative to operationalize a parallel approach to grow awareness and engagement with the PP that was accessible to all teachers in the community and beyond.

Since 2019, the PP has pursued three fundamental approaches to engage a broader network of in-service world-language teachers in the OEP process. First, the PP team has presented the PP activities at local, state, and national conferences in person and online to heighten awareness of the PP and OEP in general. Second, one of the PP directors has facilitated year-long professional development workshops with several local school districts. At these workshops, teachers are introduced to the PP activities as examples of best pedagogical practices and taught how to retain, reuse, and revise PP activities to align with their curriculum. Workshop time is provided for teachers to practice what they’ve learned by customizing PP activities for an upcoming unit. Finally, the PP has pursued local, state, and national grant funding to further support professional development opportunities for K-16 world-language teachers. Local and state funding has supported two iterations of semester-long intensive training and mentorship with a small group of K-16 teachers who work with the PP team to revise PP activities. In 2022, the PP received a two-year Digital Humanities Advancement Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to further these objectives with a larger group of teachers and to expand beyond retain, reuse, and revise to also integrate the remix and redistribute cycles of OEP. Grant deliverables include a PP Hub (https://pathwaysproject.my.canva.site/), which provides support for teachers as they engage in the 5Rs mentioned above. In addition, the funding will support much needed research that evaluates rural and urban K-12 OEP teacher practices in the humanities.

Together, these three approaches have enabled the PP team to bridge institutional boundaries by helping undergraduate students and faculty and staff strategically work with the K-12 community to produce a growing repository of renewable materials. Most importantly, the OEP process provides critical discipline-specific teacher development that fosters learning by doing.

The PP OER has sustainably and effectively grown in quantity, quality, and impact over the last four years. This is in large part due to the PP team design that, like the cogs in a wheel, empowers each entity of the team to effectively build off and work with one another. The aim of this paper is to outline key elements (people and structures) that may exist across disciplines in higher education and, specifically, for programs that support pre-service and in-service teacher development in some capacity. Table 1 provides practical steps an institution can take to also meet this aim. These steps specifically address OER ancillary materials creation, not a textbook. Nonetheless, regardless of the product, ancillary or textbook materials, these guidelines might help other institutions brainstorm ways to do this type of OEP collaboration.

Table 1

Practical Steps to Foster a K-16 OEP Partnership

|

The steps above have come from the invaluable lessons the PP team has learned and refined along the way, and yet teachers at all levels face many barriers (see Figure 1) that inhibit the transformational pedagogical experience that OEP touts (Baas et al., 2019). Recognizing and explicitly addressing these barriers is paramount. Firstly, teachers must possess or cultivate information literacy skills when searching for and ultimately selecting materials related to their discipline (Tang & Bao, 2020). This process can be time intensive and frustrating at best. While teachers of introductory level courses may find a virtual treasure trove of materials, intermediate and less commonly taught subjects (or in our case, languages) are lacking materials. Even when materials are plentiful, time is needed to review and appraise them. Once a teacher selects an OER material they’d like to reuse, a new, specific set of skills is required to revise and remix. Here again, time functions as a barrier, along with lack of reward, lack of confidence in one’s materials, and a lack of skills (Bates et al., 2007; Wenk, 2010; Windle et al., 2010). Teachers who successfully revise and remix materials may share their materials with their local network, but “seem to refrain from sharing on the Web” (Van Acker et al., 2014, p. 142), owing to what Beaven (2018) called dark reuse. Most concerning, however, is the urban-rural K-12 divide where OEP might make the greatest impact. Teachers in urban districts have greater access to professional development workshops to address and overcome these barriers while teachers in rural school districts do not (Tomlinson, 2020). Virtual workshops and strategic outreach that is inclusive of rural professional development can address these disparities, and this is the primary objective for the PP moving forward.

While not an exhaustive list, the contents of Table 1 delineate best practices that have contributed to the sustainability of the PP over the last four years. In addition, items nine and ten point to future-focused initiatives the PP has recently developed that can support open distributed learning contexts for teachers. Nonetheless, the barriers discussed are clear growth opportunities where the PP can address long-standing challenges in OEP. Moving forward, one of our present challenges is how to foster long-term OEP sustainability with in-service teachers who do not mentor pre-service teachers and attend professional development workshops because their districts mandate them. A common misconception for these teachers is that OER materials are finalized products that must fit exactly within their unit or curriculum to serve an immediate purpose. Professional development workshops can be important stepping stones to adjust these misconceptions by emphasising the process of OEP and the investment of time it will take to customize materials to better align them to the curriculum and, most importantly, for their students. Furthermore, the PP is eager to engage with teachers across state lines and measure OEP outcomes to better understand informal learning contexts in an Online Distributed Learning context. Finally, the PP has experienced challenges well documented in the OER literature with regards to the lack of redistribution or sharing back (Beaven, 2018). This is a particularly complex challenge for K-12 community outreach that is in stark contrast to most university courses that, by nature, are taught by people who have more control and can strongly encourage students to make their assignments renewable through redistribution or sharing back. As the PP engages in its next cycles of K-12 community outreach, it will be imperative to better understand and evaluate mitigation strategies to foster increased redistribution amongst K-12 teachers, including fostering digital literacy skill development in both rural and urban settings, so that PP is representative of diverse learning environments to positively impact student learning for all.

Allan, S. (2021). Four ways K-12 and higher education can collaborate on pandemic recovery. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. https://usprogram.gatesfoundation.org/news-and-insights/articles/four-ways-k12-and-higher-education-can-collaborate-on-pandemic-recovery

Baas, M., Admiraal, W., & van den Berg, E. (2019). Teachers’ adoption of open educational resources in higher education. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(9), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.510

Bates, M., Loddington, S., Manuel, S., & Oppenheim, C. (2007). Attitudes to the rights and rewards for author contributions to repositories for teaching and learning. Alt-J, Research in Learning Technology, 15(1), 67-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687760600837066

Beaven, T. (2018). “Dark reuse”: An empirical study of teachers’ OER engagement. Open Praxis, 10(4), 377-391. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.4.889

Blomgren, C. (2018). OER awareness and use: The affinity between higher education and K-12. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v19i2.3431

Blomgren, C., & McPherson, I. (2018). Scoping the nascent: An analysis of K-12 OER research 2012-2017. Open Praxis, 10(4), 359-375. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.4.905

Gimbel, E. (2018, May 16). Higher education and K-12 form partnerships to help educators and learners. EdTech: Focus on K-12. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2018/05/higher-education-and-k-12-form-partnerships-help-educators-and-learners

McGreal, R., Mackintosh, W., Cox, G., & Olcott, Jr., D. (2022). Bridging the gap: Micro-credentials for development: UNESCO Chairs policy brief form—Under the III World Higher Education Conference (WHEC 2021) Type: Collective X. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 23(3), 288-302. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v23i3.6696

Parker, K. (2019, August 19). The growing partisan divide in views of higher education. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/08/19/the-growing-partisan-divide-in-views-of-higher-education-2/

Rolfe, V. (2012). Open educational resources: Staff attitudes and awareness. Research in Learning Technology, 20(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.14395

Seaman, J. E., & Seaman, J. (2022). Coming back together: Educational resources in U.S. K-12 education, 2022. Bay View Analytics. https://www.bayviewanalytics.com/reports/k-12_oer_comingbacktogether.pdf

Tang, H., & Bao, Y. (2020). Social justice and K-12 teachers’ effective use of OER: A cross-cultural comparison by nations. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(9), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.576

Tomlinson, H. B. (2020, September). Gaining ground on equity for rural schools and communities. MAEC Rural Equity Series. https://maec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/MAEC-Rural-Gaining-Ground.pdf

Van Acker, F., Vermeulen, M., Kreijns, K., Lutgerink, J., & Van Buuren, H. (2014). The role of knowledge sharing self-efficacy in sharing open educational resources. Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 136-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.006

Van Allen, J., & Katz, S. (2019). Developing open practices in teacher education: An example of integrating OER and developing renewable assignments. Open Praxis, 11(3), 311-319. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.3.972

Van Allen, J., & Katz, S. (2020). Teaching with OER during pandemics and beyond. Journal for Multicultural Education, ( 14 )3/4, 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-04-2020-0027

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wenk, B. (2010, April). Open educational resources (OER) inspire teaching and learning. In IEEE Educon 2010 Conference (pp. 435-442). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2010.5492545

Wiley, D., Webb, A., Weston, S., & Tonks, D. (2017). A preliminary exploration of the relationships between student-created OER, sustainability, and students’ success. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i4.3022

Windle, R. J., Wharrad, H., McCormick, D., Laverty, H., & Taylor, M. G. (2010). Sharing and reuse in OER: Experiences gained from open reusable learning objects in health. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2010(1), Article 4. http://doi.org/10.5334/2010-4

Wolfenden, F. & Adinolfi, L. (2019) An exploration of agency in the localisation of open educational resources for teacher development. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(3), 327-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1628046

Partnering Higher Education and K-12 Institutions in OER: Foundations in Supporting Teacher OER-Enabled Pedagogy by Kelly Arispe, Ph.D. and Amber Hoye, M.E.T. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.