Alison Mead Richardson

Botswana

This paper reports on a longitudinal, ethnomethodological case study of the development towards flexible delivery of the Botswana Technical Education Programme (BTEP), offered by Francistown College of Technical & Vocational Education (FCTVE). Data collection methods included documentary analysis, naturalistic participant observation, and semi-structured interviews. The author identifies and analyses the technical, staffing, and cultural barriers to change when introducing technology-enhanced, flexible delivery methods. The study recommends that strategies to advance flexible learning should focus on the following goals: establish flexible policy and administration systems, change how staff utilization is calculated when flexible learning methodologies are used, embed flexible delivery in individual performance development and department/college strategic plans, ensure managerial leadership, hire and support permanent specialists, identify champions and share success stories, and address issues of inflexible organisational culture. This study may be of value in developing countries where mass-based models are sought to expand access to vocational education and training.

In institutions, translating policy into action can be precarious and time-consuming. Wright, Dhanarajan, and Regu (2009) point out, “Government and institutional personnel in developing countries often decide to employ e-learning or online learning without fully realizing what it means for their students and their institutions.” This study confirms and builds on this statement, focusing on the impact on institutional staff.

Botswana is one of Africa’s success stories (Siphambe, 2000; Freeman & Lindauer, 1999). Following independence in 1966, the country has been transformed from one of the least developed countries, with 90% of the population subsisting in drought-prone agriculture and a per capita income of about US$80, into a middle-income country, with 50% of the labour force employed in formal sector activities and a per capita income estimated in 2004 at US$3,451 (Hough & Short, 2007).

Despite this rapid transformation, Botswana faces a huge challenge in developing a skilled population, which can further contribute to national development. This is partly due to the capacity of the education system to meet demand. Due to the successes of the focus on the goals for Millennium Development and Education for All, most African countries are grappling with the question of how to increase access to post-secondary education (Perraton, 2000). Botswana is no different. “There is also evidence that the economy is unable to cater for the increasing numbers that have emerged from the expansion of primary schools” (Akoojee, 2005). A net primary enrolment ratio of 100 was reached in 2000 (Botswana Education Statistics Report, 2002). This success has consequently expanded the secondary sector and increasing numbers of secondary leavers are putting pressure on the provision of post-secondary, or tertiary, education. The World Bank, in its Education at a Glance series, reports a gross enrolment ratio for secondary education that increased from 38 in 1990 to 73 in 2005 (World Bank, 2007).

Educational development in Botswana takes place within the context of six-year rolling National Development Plans (NDPs). These are essentially plans for public spending and human resource use, and annual budgets are used as instruments for converting a development plan into a programme for action. The plan under which this study took place is NDP9, which states that the Department of Technical & Vocational Education & Training (DTVET) should do the following:

The guiding policy in education in Botswana is the Revised National Policy on Education (RNPE) 1994. In it, the Government of Botswana (GoB) has acknowledged that vocational education and training (VET) is crucial to the country’s economic diversification from an agro-based to an industrialised economy. The RNPE 1994 indicates that the Government should take responsibility for initial broad-based vocational education, while employers should be responsible for more job-specific or specialised vocational training.

The Vocational Education & Training (VET) Policy of 1997 focused on the need to expand access to VET and to make it more inclusive and equitable whilst addressing issues of quality and cost-efficiency. The policy identified that traditional delivery methods do not meet the needs of the broader profile of VET students existing in the country.

3.17 Traditional modes of programme delivery are widely used but their exclusive application does not always meet the requirements of a modern labour force and are not adequate for certain target groups. There is a need to diversify modes of delivery. Curricula and programmes will emphasise:

- flexible modes of delivery that will facilitate the achievement of competencies by trainees

- modes of delivery that are adaptable to new technologies and responsive to technological changes

3.18 Through pilot programmes, new modes of delivery will be explored. These include development and testing of different modes of distance education. (GoB 1997)

Clearly the educational policies are pointing in the direction of more flexible teaching and learning methodologies with an emphasis on distance learning provision and the use of technology to address issues of increased access and equity and improved quality with cost-effectiveness.

The first choice for most secondary school leavers is university but tertiary provision has not expanded at the same pace as basic education. Of the approximately 20,000 senior secondary school leavers annually, there is a net enrolment rate of less than 12% in post-secondary education (GoB, 2005). Projections from the Planning Unit at the Ministry of Education & Skills Development (MoESD) suggest that by 2016, this number will have risen to 37,000. Information from the University of Botswana suggests that currently out of 20,000 Form 5 leavers each year 18,000 would be traditionally eligible to apply for university. The university admits 5,000 students, of whom around 3,500 are school leavers, 1,000 are adult workers, and 500 are moving from one qualification to another. This leaves approximately 14,500 eligible school leavers unaccepted at the university. With the university currently taking only 3,500 school leavers each year and teacher training colleges admitting about the same number, there is clearly a huge shortfall in tertiary provision with perhaps more than 10,000 senior secondary school leavers, each year, with no tertiary destination.

Where do these young people go? Some go to the Agricultural College but increasingly they are turning to vocational education and training, traditionally delivered by government institutions but more recently by the growing number of private institutions in the country. Of the 124 institutions registered by Botswana Training Authority (BOTA) in December 2008, more than half are private providers.

The Government has long recognised this impending bottleneck in tertiary provision and, through the national development planning system, has taken the following actions:

Taking up the mandate provided by the 1997 VET Act, a major curriculum initiative was launched by DTVET in the same year to develop and implement the Botswana Technical Education Programme (BTEP). Designed in collaboration with industry and the Scottish Qualifications Authority to meet the needs of a modern and flexible economy and to encourage graduates to become lifelong learners, BTEP was introduced in 2001. It is a modularized, outcomes-based programme, which is designed to be delivered flexibly in a variety of modes to a wide range of different learners using individualized, constructivist methodologies.

The DTVET Strategic Plan 2004-2009 states that by the end of the plan period, 20 units of BTEP will be offered by distance learning. Budget lines have been allocated to facilitate this; however, the principal of FCTVE reports that these funds have been held centrally and have not been made available to the college.

The introduction of new teaching and learning technologies at FCTVE was essentially a naturally-occurring experiment, and it was important to find out what people did to make sense of the process. Approaching the study without a pre-determined hypothesis enabled themes and issues to emerge from the fieldwork rather than from the hypothetical standpoint (Patton, 1990). Flexibility in research methodology was important so the design could unfold as the fieldwork progressed. A process study focuses on how something happens rather than on the outcome or results.

Documentary analysis was a critical element in the data collection. A good deal can be learned about an organisation by its documented strategic plans, policies, and procedures. In addition, minutes of meetings can be a rich source of information in a longitudinal study as they document priorities and discussions on salient issues. As the research progressed, it became clear that there was a wealth of documentary evidence, which had not been identified initially, such as workshop flipcharts, programme descriptions, and reports from other consultants and technical assistants. These documents were also analysed and provided rich data; for example, workshop flipcharts from sessions with heads of departments (HoDs) showed how more flexible approaches became part of the college discourse over time.

Participant observation was suitable as the researcher was an adviser to the college staff and carried out the role of ‘expert’ in distance and e-learning. The study progressed with what Denzin calls an “omnibus field strategy” in that it “simultaneously combines document analysis, interviewing, direct participation and observation, and introspection”(1978). Daily interactions were focused on the process of implementing flexible learning programmes. The choice of research methods was based on the assumption that understanding emerges most meaningfully from an inductive analysis of detailed descriptive data gathered through direct contact with participants (Patton, 1990). Some specific assumptions were made:

This last assumption is potentially very wide. There is a complex relationship between research and policy. Research does not feed directly or simplistically into policy-making.

The study used a purposive sample: Respondents were specially selected to provide information-rich responses. Some respondents were selected because they held a certain role and responsibility within the system and others because of what they were doing, or not doing, in relation to the move towards more flexible teaching methods. During the initial exploratory fieldwork, observations were made and emerging patterns were identified. Later, specific respondents were selected to provide more focused information on specific issues and an attempt was made to explore the observed behavior in more detail. Patton (1990) calls this a move from an exploratory process to confirmatory fieldwork. Interviews were conducted with more than 30 respondents, including policy-makers, college managers, and lecturers. Key individuals, such as the college principal and lecturers who were of particular interest, were interviewed two or three times.

There were some important constraints on the research. One of the main concerns for a naturalistic participant observer is the issue of reflexivity. In qualitative research, the researcher is the research instrument (Patton 1990; Cohen, Manion, & Morrison 2000). Reflexivity acknowledges that qualtitative researchers are inevitably part of the social situation they are researching and inescapably have views and interpretations of the meanings of that social situation. This researcher had to be very careful to guard against imposing her own constructs on respondents during interview and content analysis. It was necessary for the researcher to closely monitor interactions with respondents in order to avoid bias.

The common constraint of time applied because the research was spread over a two-year period and large quantities of qualitative data were collected. It was important to design time-efficient data collection methods in order to achieve the detailed level of research required. The sheer weight of data that is collected during participant observation and the research skills needed to effectively analyse and attribute meaning to this enormous quantity of data require a large allocation of time. Field notes are of critical importance for a participant observer. The field notes taken during a longitudinal qualitative survey cover a vast amount of data, which must be recorded and analysed.

Initial ideas on the research methodology had to be adapted when it became clear that they were unworkable. An early plan was to request key staff members to keep a journal or diary of their activities and their reflections on those activities as they learned to use the new teaching and learning technologies. However, it quickly became clear that staff members were unlikely to commit to doing this in a sustained and useful way, so this method was dropped. The planned use of Internet chat systems for conducting interviews also proved to be unworkable as respondents did not have the required levels of skills or confidence in the use of the technology. This meant that the initial research design for interviews had to be re-thought in the light of the context of the respondents.

The BTEP Guide to Implementation (GoB, 2004) states the underlying principles of the BTEP curriculum as a commitment to providing flexible entry and exit points, flexible access to learning and assessment, and equality of access for all potential candidates. Colleges are guided to make decisions on how they will provide a BTEP candidate-centred approach to learning and flexible delivery of BTEP units.

In reality, whilst the design may have been flexible, many teaching staff have limited teaching skills, which means the delivery has become rigid and inflexible, leaning towards didacticism with many staff unwilling to work flexibly and courses being over-taught (Morris, 2007). This view is reflected by comments from college staff and managers.

The design of BTEP is very flexible, but it is the implementation which seems to be rigid. Some teachers hang on to the old ways of teaching and then we don’t feel the full potential of the programme.

It is not flexible – well maybe in name only. It is outcome-based but delivered within very rigid structures. When we try to deliver more flexibly then other people in the college want to do it in the traditional way.

So far, BTEP delivery has been only by conventional face-to-face educational methods. But in tandem with the creation of BTEP, DTVET planned to broaden the delivery methods of VET in order to meet the demands of increasing access. In the late-1990s, DTVET entered into a partnership with the European Union (EU) to build a new flagship technical college in Francistown in the north of the country. This is the seventh technical college in DTVET’s stable and the new college is mandated to offer BTEP nationally through both “traditional and flexible and distance education methods.” Along with building the new college and providing advanced ICT networking infrastructure, the EU/GoB funding provided a technical assistance (TA) team. The TA team included experts in ICT networking, ICT systems administration, instructional design, e-learning, and distance education. The role of the team was to assist in operationalising the new college and to assist the staff of the college to introduce new teaching and learning technologies. Because of their expert knowledge, the members of the team were contracted to be change agents in the process of bringing flexible teaching and learning approaches into the government VET system, starting with Francistown College of Technical & Vocational Education (FCTVE). The intention was to set up an innovative new college that would pioneer the use of ICT in teaching and learning in technical and vocational education and that would provide a model for other institutions to follow.

The college started operations in April 2007 with an initial staff complement of 35 making preparations to offer BTEP in 10 vocational programmes: Business, ICT and Multimedia, Hospitality Operations, Travel and Tourism, Clothing Design and Textiles, Hairdressing and Beauty Therapy, Construction, and Engineering.

In order to start the transition to flexible delivery, a number of activities were initiated by the TA team:

Remembering the classic Bates ACTIONS model (Bates, 1995), staff access was the first consideration, both in terms of physical access to the technology and of the skills to use it. DTVET provided a high-specification local area network at the college with Internet access through the Government Data Network. Following the recommendations of the Botswana National Strategy for eLearning Report (Uys, Mead, Fouche, & Adam, 2004) open source was chosen for the learner management software, and Moodle was recommended and accepted by the policy-makers.

A systematic approach to staff capacity building was advocated (Le Cornu et al., 2004) starting with a training needs analysis survey of all the managers, administrators, and lecturing staff. This provided detailed information on the skills and confidence levels of staff in terms of computer literacy and new teaching and learning methodologies. From this, a programme of capacity-building activities was developed for which staff members could enrol. Seminars and workshops were held to introduce new concepts in flexible teaching and learning as well as new pedagogic approaches and training in using Moodle. After making it possible for staff to start gaining the skills and knowledge they needed, it was believed that teachers would begin to re-design their BTEP units for flexible delivery.

There was a high level of participation in staff development activities in the first few months but interest diminished and it became problematic to get people to attend sessions they had signed up for. This was believed by the TA team to be due to a lack of interest on the part of college managers which quickly filtered down to staff. As the departments moved towards finalizing their preparation for students it became easier for them to rely on traditional approaches. One lecturer commented on the amount of time it takes to develop resources for e-learning delivery through Moodle; another talked about the “risk” of offering e-learning. A good number of lecturers attended all the staff development sessions offered but did not translate that into the development of new approaches to teaching. One staff member saw this as a challenge to be addressed by management.

The other challenge for management, especially HoDs, is staff development. People attend staff development workshops just to satisfy the expectations of the HoD – they are not really interested in learning. This means that they cannot learn – and even if they do, they are not putting it into practice. So HoDs should undertake to do the follow-up and make sure that when lecturers get new skills that they follow through and create the new learning resources – even create e-learning units.

All teaching staff members were involved in the first college strategic planning cycle, and flexible learning was specified as an initiative to meet five strategic goals. Teaching staff commented that it was important to have policy and strategic plans that specified flexible learning for them to accept that this was something “coming from the top.”

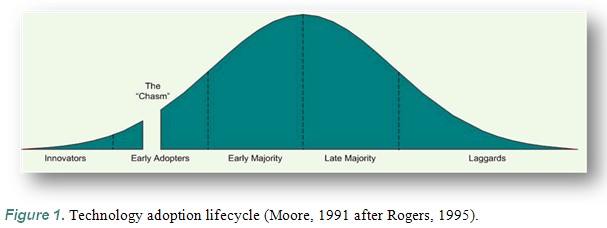

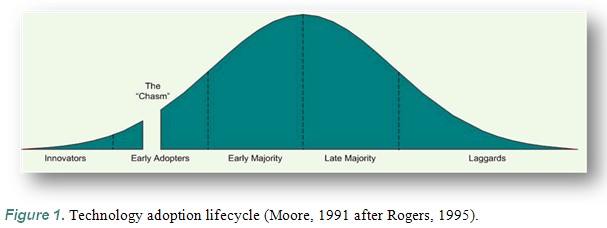

A classic technology adoption lifecycle was noted (Figure 1) with a few encouraging “innovators and early adopters.” An interesting point about these colleagues is that unlike the model proposed by Rogers (1995) they were not unhappy with lecture-style teaching and initially had no fascination with technology. When asked why they had taken up distance and flexible delivery, some expressed a desire for personal development as lecturers; another said “because you asked me to!”

Individual support to these staff resulted in a distance learning unit in Beauty Therapy being the first to enrol students to the college. Other early adopters developed flexible learning units in Hospitality Operations, Business, and Multimedia, and these staff benefited from individual coaching.

Change took place for one lecturer because she needed to find a solution to a lack of staff in her department; she was the only lecturer appointed to FCTVE. Distance delivery was identified as the solution. She is now committed to developing her whole programme in a flexible delivery format. She commented,

I wasn’t planning to do distance education when I came to FCTVE. But when I found I was the only staff member, what else could I do? And the PTEO supported me. Now I’ve learned to do distance education, I like it. I now know that it is important to increase access to BTEP with distance learning but I miss my students … you know, seeing them every day.

In fact, she raised two interesting issues:

Research into the uptake of online education by faculty carried out by Berge (1998) reveals that barriers to online teaching and learning can be situational, epistemological, philosophical, psychological, pedagogical, technical, social, and/or cultural. It is important to note that the majority of research into faculty adoption of technology has taken place within a context of higher education not TVET. We have yet to experience the breadth of the issues identified by Berge but can categorise the challenges we have encountered so far as technical, human resource, and cultural. There is a strong cultural emphasis on didactics and lecturing in the college, and this has not yet been sufficiently exposed and discussed in the initial activities. Research by Zellweger Moser (2007) in three research universities in North America indicates that time is one of the most important considerations for faculty when deciding whether to adopt technology. The unique situation at FCTVE is that many teaching staff members were employed at the college for up to 18 months before students joined the college, so lack of time to prepare new learning materials should not have been an issue.

There are several systemic barriers to the promulgation of flexibility at the college. The main one is the restrictive nature of government staff conditions of service. In the Botswana government system, teaching staff are contracted for office hours and there is little flexibility in the system. Staff cannot be paid for working outside these hours. In order to offer evening classes, external part-time staff must be hired. Staff members report dissatisfaction with this system. They would be prepared to work outside hours to support flexible delivery but expect remuneration for this. Time off in lieu is not always acceptable. In addition, staff members report a fear of being charged with “under-utilisation.” They feel they are judged by their contact hours with students, and flexible approaches, which reduce contact time, are viewed with suspicion. A recommendation was made to college management that the system of calculating staff teaching hours needed to be adapted to provide for flexible delivery. In distance learning, writing learning materials is the teaching and should be provided for in the same way as contact hours are in face-to-face teaching. As yet, the staff utilization mechanism has not been reviewed.

This was also an issue noted by Palmieri (2004, p. 92) in the move to flexible learning in vocational colleges in Australia in the 1990s. She quotes from a report of the ANTA Flexible Delivery Working Party (1992, p. 21): “Current input-oriented key performance indicators based on student contact hours and the utilisation of teachers and facilities are inappropriate for flexible delivery. They are a significant barrier to innovation and change.”

Lecturers also voiced concerns about the level of understanding of the issues involved in flexible delivery by college managers.

I’m not sure if the college managers really understand what flexible learning is all about. This is important because when you do flexible learning then some things have to be changed from the way they were done before. We need access to the LRC and even to the PC Labs in the evenings and at weekends for our students but that is quite difficult right now.

College managers, in turn, voiced concerns about the level of understanding of DTVET officers when they included distance and e-learning in their strategic plans.

It (distance and flexible learning) is reflected only as far as policy formulation is concerned. I have doubts about DTVET’s conviction and commitment to the implementation of distance and flexible learning. There is no evidence of them putting up structures to make sure it is realised. There is no unit or even an officer in DTVET for distance and flexible learning, so where is the co-ordination going to come from?

One of the biggest concerns reported by the college managers is the lack of counterparts to the TA team, which are needed for effective skills transfer. This is part of a wider concern about the lack of human resource for new teaching and learning technologies. There are no positions in the establishment to support the introduction of flexible learning. Apart from the TAs, there are few people with sufficiently developed technical or pedagogic skills to develop print-based or computer-based materials for flexible learning. A concern voiced by both managers and staff is that after the TA team has left the college, flexible learning will collapse, so in the words of one lecturer, “why bother?” Even the principal has stated that the lack of provision of specialist staff to support flexible learning suggests to him that efforts may cease when the TA team leaves the college: “It’s the issue of permanence. The TAs are here on a mission but when the TAs are gone, we think that flexible learning will collapse. That influences peoples’ thinking – even mine.” And one lecturer commented, “The problem comes now that it is time for the TAs to leave – who will drive the process forward now and support those teachers who have already started?”

It is clear that the project approach to change has substantial drawbacks. However, most staff and DVET officers acknowledge the need for external expertise with the introduction of new teaching and learning technologies. There is still some question about the efficacy of the use of TAs as change agents. Rogers (2003) points to the differences, or heterophily, between change agents and what he calls the “client system.” Rogers states that change agents tend to be substantially different from the people they are trying to persuade to change in terms of “language differences, socioeconomic status and beliefs and attitudes” (2003, p. 368).

Even though we asked the “tough institutional policy questions” in advance, as advocated by Gellman-Danley and Fetzner (1998), and identified the challenges that were likely to arise, it was difficult for administrative colleagues to focus on, and deal with, these in abstract. What we found – as did Berge – was that administrative and policy barriers that are encountered during the development and delivery of pilot programmes can usually be overcome in order to solve specific problems (Berge, 1998). When presented with a problem that needed solving, support staff displayed a flexibility and a willingness to help that was not evident when similar requests were made at the planning stage. When asked about this difference in response, one senior administrator commented, “Well you had students coming and I couldn’t let you down. I wanted to help you to make it work. But next time you will have to stick to the government system.”

Such comments point to Fullan’s (2006) statement, “In order to accomplish this goal [organisational transformation] it is necessary to change not only individuals but also systems.”

A cross departmental working group was convened to develop a strategy for implementing flexible learning at the college. In this forum, TA teams had an opportunity to explore the process of introducing flexible learning in more detail with heads of departments and other key staff. A phased approach was agreed upon, which started with challenging each department to find at least two ways to make their BTEP delivery more flexible. Unfortunately some departments proposed offering a short course, full-time and face-to-face, rather than the more technologically-enhanced deliveries envisaged. However, individuals in other departments did start to embrace more flexible content delivery methods and started using Moodle to present course content and formative assessments.

The working group suggested that the implementation of flexible learning should work through the government performance-based rewards system (PBRS) and individual staff performance development plans. The Government of Botswana has a highly defined performance management system, based on the balanced scorecard method of strategic planning (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). This system provides for individuals to achieve specific rewards for excellent performance over and above their salary. The working group proposed that enshrining activities associated with flexible learning in personal objectives and linking them to performance rewards would create an incentive to ensure the objectives are fulfilled to contribute to professional advancement. Although this was discussed with college managers, the concept did not filter down to staff and only one staff member (working closely with the TA team) included flexible delivery of a BTEP unit as an annual objective in the performance development plan. Unfortunately, both college staff and managers confirmed that the balanced scorecard system is not well understood or implemented: We understand how to fill in the forms, but we don’t really understand the purpose,” said one lecturer. And a college manager commented,

It is a good system but … there is not really a good understanding of how to use it effectively to help reach our strategic goals. Neither the staff nor the management really understands it because it is very complex.

One of the strategies to address the concern about lack of expertise in distance education at FCTVE, post-TA project, was a proposed collaboration between FCTVE and BOCODOL, the parastatal organisation with responsibility for improving access to school equivalency and vocational programmes for out-of-school youth, using open and distance learning methods. A proposal was made to collaborate on the development of BTEP Key Skills units, which can be studied at a distance through BOCODOL. Students with completion certificates from BOCODOL would then be given priority entrance to vocational programmes. This would relieve Key Skills staff from some face-to-face teaching and allow them to focus on remedial work and assessment, bringing potentially greater efficiency and quality to the system. Collaboration between DTVET & BOCODOL on distance delivery of vocational programmes is specified in NDP9, and DTVET, FCTVE, and BOCODOL management expressed their support for the collaboration. A Memorandum of Understanding was drawn up, and a Key Skills by DE planning workshop developed a course specification. However, neither has made progress since the end of the TA project.

FCTVE is a highly resourced and well-provisioned college, especially in the context of developing African countries, but we have seen that providing access to the technology and skills is not enough. The policy framework is in place to support the introduction of flexible learning but this is clearly not enough to make it happen. There is a fissure – another chasm, perhaps – between policy and the adapted organizational processes needed to bring about the changes specified in the policy.

The possible strategies for overcoming some of the challenges are both long- and short-term and are in the hands of both DTVET and the college. To ensure that the move towards flexible learning continues, focus is needed in key areas:

Palmieri’s experience in Australia shows that these are not simply issues for developing countries, and although a one-size-fits-all approach is not advocated, it is clear that lessons can be learned from VET systems that have already made the move towards flexible delivery. Palmieri’s experience of national policy on utilisation of VET teachers is reflected at DTVET. Although the policy and policy-makers are clear about the need for flexibility, the management structures and systems have not been adapted to facilitate that flexibility. The words of Greville Rumble are echoed here, who says that flexible learning is more about the organization being flexible than the students (personal communication, 2006).

What is the future of flexible learning at FCTVE? This research is ongoing and lessons are still being learned from the process. It is hoped that more colleagues will cross the chasm and a foundation can be built for flexible learning at FCTVE that serves learners, teachers, and the Botswana VET system. It is also hoped that the chasm between the policy objective of flexible delivery and the management structures to support it can be reduced. The college principal and a lecturer have the last word respectively.

Now that we have come so far with flexible learning, we want to do more. We’ve seen the successes and learned where we need to make changes, so we have started. We now need to consolidate what we have achieved and work with those people who have not yet come on board.

Moving to distance and e-learning should be treated as compulsory – teachers should not be given the choice whether to do it or not. Management should be strict and follow up and make sure everyone does it – that’s how it works with us Africans – we need to be made to do something before we can appreciate that it is a good idea.

Akoojee, S. (2005). Private further education and training in South Africa. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council. Retrieved February 10, 2007, from http://www.hsrcpublishers.co.za/freedownload.asp?id=1995

ANTA (Australian National Training Authority) (2000). Australian flexible learning framework for the National Vocational Education and Training System 2000 – 2004. Brisbane: Australian National Training Authority. http://flexiblelearning.net.au

Bates, A.W. (1995). Technology, open learning and distance education. London: Routledge.

Bates, A.W. (2005). Technology, e-learning and distance education. London: Routledge.

Berge, Z. (1998). Barriers to online teaching in post-secondary institutions: Can policy changes fix it? Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 1(2). Retrieved October, 2006, from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/Berge12.html

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Freeman, R.B., & Lindauer, D.L. (1999). Why Not Africa? (NBER Working Paper No. 6942). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved December, 2008, from www.nber.org/papers/w6942

Fullan, M. (2006). The future of educational change: System thinkers in action. Journal of Educational Change, 7, 113-122.

Hough, J., & Short, P. (2007). Education policy fiscal review. Ministry of Education, Government of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana.

Gellman-Danley, B., & Fetzner, M. (1998). Asking the really tough questions: Policy issues for distance learning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 1(1) Retrieved September, 2006, from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/danley11.html

Government of Botswana (1997). Vocational education and training policy. Gaborone, Botswana.

Government of Botswana (2002). Botswana education statistics report. Gaborone, Botswana.

Government of Botswana (2004). BTEP guide to implementation. Department of Technical & Vocational Education & Training, Gaborone, Botswana.

Government of Botswana (2005). Tertiary education policy for Botswana: Challenges and choices. (Tertiary Education Council, consultation paper). Gaborone, Botswana.

Kaplan, R.S., & Norton, D.P. (1996). The balanced scorecard. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Le Cornu, P., van der Merwe, D., Moore, D., Nduba, S., & Rennie, F. (2004). Institutional policy for vocational education and training delivery. In G. Rumble & L. Moran (Eds.), Vocational education and training through open & distance learning. London: Routledge Falmer.

Moore, G.A. (1991). Crossing the chasm. New York: Harper Business.

Morris, I. (2008, February). BTEP: A personal critique. Presentation to QAA Stakeholders Conference.

Palmieri, P. (2004). The Australian flexible learning framework. In G. Rumble & L. Moran, (Eds.), Vocational education and training through open & distance learning. London: Routledge Falmer.

Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). California: Sage Publications.

Perraton, H. (2000). Open and distance learning in the developing world. London: Routledge.

Rogers, M.E. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.) New York: Free Press.

Siphambe, H.K. (2000). Education and the labour market in Botswana. Development Southern Africa 17(1).

Uys, P., Mead, A., Adam, L., & Fouche, J.(2004). Feasibility study report to develop a national strategy for e-learning in Botswana. European Union/DTVET, Gaborone, Botswana.

World Bank (2007). Education at a glance. Botswana: World Bank.

Wright, C.R., Dhanarajan, G., & Reju, S.A. (2009). Recurring issues encountered by distance educators in developing and emerging nations. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(1). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/608/1180

Zellweger Moser, F. (2007). The strategic management of e-learning support: Findings from American research universities. New York: Waxmann Munster.