Patricia W. Neely and Jan P. Tucker

Kaplan University, USA

Many colleges and universities are expanding their current online offerings and creating new programs to address growing enrollment. Institutions often utilize online education as a method to serve more students while lowering instructional costs. While online education may be more cost effective in some situations, college decision makers need to consider the full range of cost implications associated with these online offerings. The unbundling of faculty roles in online distance education programs is one cost consideration that is often overlooked. As the faculty role has become more distributed, so have the costs associated with providing instruction and instructional support. This paper reviews the hidden costs associated with the unbundling of the faculty role and presents a framework for calculating the true costs of the unbundled faculty role.

Keywords: Faculty roles; unbundling; higher education; online education; faculty costs

Online distance education programs are growing. Allen and Seaman (2008) reported a 12% increase in students taking at least one online course from 2007 to 2008. The growth is expected to continue over the next five years with estimates placing the number of students taking online classes in 2014 at over 18.5 million students (Nagel, 2008). Universities are expanding current online offerings and creating new programs to address growing enrollment. At the same time that online enrollments are increasing, most colleges and universities are facing unprecedented pressures to cut costs. State funding for higher education is being cut dramatically and university endowments have decreased in value (Stratford, 2009). In response to the growing pressures to reduce costs, many colleges have looked to distance education, particularly online education, as the primary method for reaching more students while lowering instructional costs. Studies have shown that while online education may be more cost effective in some situations, college decision makers need to consider the full range of cost implications associated with online education. The unbundling of faculty roles in online distance education programs is one cost consideration that is often overlooked. Interviews were conducted at a major regionally accredited online university to determine the true cost of the development, launch, facilitation, and maintenance of a graduate business course. The data, while limited to one three-credit graduate course at one university, is presented as a means of opening the discussion of the true cost of unbundling faculty roles in online education.

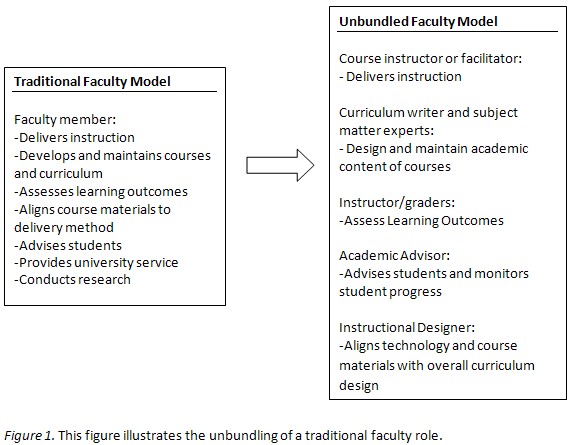

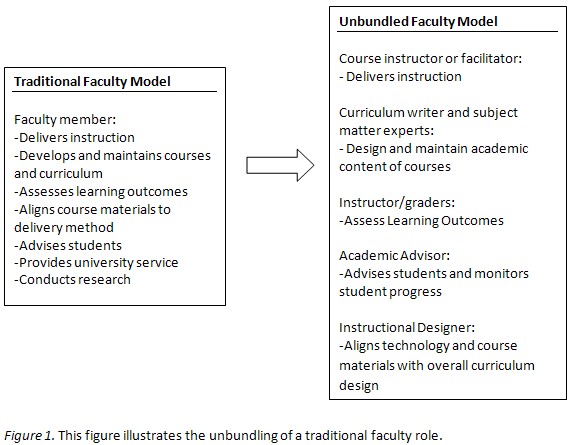

The unbundling of faculty roles begins with determining the core faculty responsibilities associated with the institution. For example, Franklin University has identified three principle faculty functions including leadership, instruction, and curriculum quality (Hagerott & Ferezan, 2003). The unbundling of these roles allows the university to assess, manage, and utilize resources based on each of these functions. It also allows the faculty to focus on their areas of expertise. Faculty members with training in curriculum design are involved in developing courses, while those with experience delivering instruction are able to focus on facilitating the course. In a traditional faculty model the faculty is responsible for both the content and delivery along with other functions like supervising graduate students, advising students, conducting research, and serving on university committees. In an online classroom this would also entail being responsible for technology functions. Unbundling these roles separates the instructional from the delivery activities and redistributes them (see Figure 1).

The unbundling process allows faculty, to some degree, to be involved in the processes in which they have the most experience and expertise. This specialization may contribute to the overall quality of the curriculum developed but it may also cause the teaching faculty to feel they are too far removed from the material developed to teach it effectively (Sammons & Ruth, 2007). Unbundling faculty roles help administration to assign costs to specific components of the design and instruction of a course, but determining exactly how to calculate and assign these costs can be challenging. As enrollment in online classes continues to grow and universities continue to feel the pressure to adapt by expanding their course offerings in an effective and efficient manner, the problem of how to adequately budget these functions will continue to be an issue. This paper examines some of the costs that are often overlooked when allocating costs to instruction and design in an effort to increase awareness among those tasked with budgetary responsibilities in higher education institutions.

The concept of unbundling is not new. The problems associated with the bundling of faculty roles, for example faculty being responsible for areas in which they were not trained such as advising students, counseling, credentialing, and course development, were first introduced in the 1970’s (Trout, 1979; Wang, 1975). Research has suggested that there is often a negative correlation between faculty time spent on research and faculty time spent on teaching and that often instructors feel that one must be sacrificed for the other (Linsky & Straus, 1975; Feldman, 1987, Fairweather, 1993). The idea is that if the instructional role is disseminated too widely, instructors will become ineffective in all roles. The theory behind the unbundling of the teaching role is that it would improve both the quality and the cost effectiveness of learning (Wechsler, 2004).

Most online faculty members today are hired specifically to work with students in a facilitator’s role around the course content. The unbundling of the traditional faculty role results in the need for a number of support personnel. Faculty supervisors, trainers, instructional technologists, academic advisors, and graders are used to support the faculty member. Schuster and Finkestein (2006) indicate that information technology may be a contributing factor to the unbundling of the faculty role as higher education institutions are pressured to increase the speed at which they deliver content to keep up with student demand. Over twenty years ago, Ljosa (1988) indicated that distance education must focus on the communication between teachers and students to facilitate learning in an online environment, which supports the concept of teachers focusing on teaching.

The unbundling of faculty roles results in a number of challenges for online colleges and universities. At a time when state budgets are shrinking and pressures to contain costs have risen, the unbundled faculty role makes it increasingly difficult to calculate the actual costs of instruction for a single course (Neely, 2004). From a management perspective, an increased number of support personnel leads to additional activities involved with hiring, training, and supervising individuals in specialized roles.

In the traditional university structure, the department or college is a cost center, and budgets and reports on instructional activities are contained within the department. Department chairs and university administrators who take an accounting or historical approach to costing in higher education are able to attribute actual expenditures to each activity (Rumble, 2001). When costs for instructional activities are included in a department budget, allocating the costs on a per course basis becomes a matter of bookkeeping wherein direct costs are attributed to a single activity or course (Brinkman, 2001). Costing efforts in higher education are often fraught with problems due to the fact that the true costs of using the building and equipment are often not reported correctly and many costs are considered joint production costs (Winston, 1988). Finkelstein, Frances, Jewett, and Scholz (2000) indicate that duplication of efforts in higher education resources reduces costs and that course preparation is the function that allows the most duplication of faculty effort. Disaggregating the components of the faculty role may change the cost structure in higher education. Trying to determine how much change in cost and if that change is positive is challenging.

As the faculty role has become more distributed, the costs associated with providing instruction and instructional support have been dispersed to multiple cost centers across the university. Faculty salaries are tangible and easy to account for in budgets (Palloff & Pratt, 2007). Less tangible and more difficult to identify are supervisory costs, training costs, and other support costs necessary to keep online courses functioning. Examining multiple budgets to identify and allocate costs to a specific course is a complex undertaking. To properly allocate costs, the activities of all instructional support personnel would need to be recorded and allocated to a specific course. In doing so, the costs from multiple departments would need to be gathered and calculated on a per course basis.

With the unbundled faculty model, new hierarchies are created within the university to support instructional activities. What does it cost to create a new department dedicated to curriculum development, academic advising, or instructional technology? Calculating the costs goes beyond allocating an instructional technologist’s salary to each course supported. Administrative support, equipment, technology, training, and supervision must also be allocated to course activities to obtain the true instructional costs for an online course.

Recruiting, hiring, and training activities proliferate with the unbundled faculty model. The traditional faculty model tasks the department chair with recruiting, selecting, hiring, and training new faculty with support from the human resources department and faculty committees. Hiring multiple individuals in highly specified roles also requires increased support for human resource activities as increased numbers of individuals are hired for these roles and the activities are continuous. Hiring is typically based on the semester system in a traditional faculty model. Many online institutions have multiple terms throughout the year, resulting in continuous hiring and training of instructional support positions. Increased administrative support is required for processing the hiring paperwork, for payroll, and for monitoring faculty performance.

Multiple supervisors are needed with specialized expertise to monitor and evaluate the performance of individuals in specialty roles. Instruction, training, and supervision are ongoing in the unbundled faculty model as multiple part-time instructors are used in various capacities to facilitate learning. The instructional cost per student is a growing concern for higher education institutions as they struggle to contain costs while providing quality education in a technologically rich and competitive environment. It is important that all costs be considered when determining the yearly budget for faculty and when calculating the true capital-labor ratio in these institutions.

The researchers used a case study approach to gathering data on the costs of unbundled faculty roles. The first phase of the research involved the collection of data and general information on the unbundled faculty role and on costs in higher education. The second phase of the research included identifying the course to be studied. Once a course was selected, university documents were examined to determine course instructional support. The final phase in the research included interviewing department administrators. The research questions that guided the gathering of data included the following:

A limitation of this study is the very narrow focus of examining one course at one institution. This case study may be of limited help in drawing broad generalizations about the costs of the unbundled faculty role at another institution or across institutions. Although limited in scope, this case study acts as a starting point for the examination of the cost implications for the unbundling of faculty roles in online institutions.

A review of each of the unbundled faculty roles identified in Figure 1 reveal that the process for identifying costs must begin by creating a framework for the costing process. The researchers determined that a modified activity based costing approach would be used. According to Horngren and Harrison (2009), activity based costing (ABC) examines costs that are the building blocks for measuring the costs of services, such as an online course. Traditional costing systems only measure inputs, such as salaries and administrative activities; whereas, activity based costing provides a mechanism and methodology for also measuring the cost of outputs (Granof, Platt, & Vaysman, 2000). While ABC is frequently used in business models it is not as prevalent in institutions of higher education. Higher education accounting systems typically rely on fund accounting, which may not provide the information administrators need to make strategic decisions within their institutions. Granof, Platt, and Vaysman (2000) found that the usefulness of allocating indirect costs based on factors by which they are most influenced, afforded by ABC, was just as applicable to universities as it was to industry. With an activity based costing methodology, individual activities are identified and the resulting costs attributed to an individual, online course at the university.

The process for identifying the costs of the unbundled faculty role began by reviewing each of the unbundled faculty roles identified in Figure 1. The costs for all roles were examined and calculated, except the academic advising role. Over the past 30 years, the academic advising function has been increasingly segregated from the role of a faculty member (Hrabowski, 2004). Specialized positions have been created within most colleges and universities to address student advising activities. For the purposes of this study, it was determined that academic advising activities were provided through the same advising centers for students in both traditional courses and in online courses. Academic advising has been segregated from the faculty instructional role at many universities using a traditional faculty model. The researchers determined that calculating the costs for academic advising would not be undertaken as part of this study because advising was centralized for students in both online and on-grounds courses.

The first step in conducting a study of the costs of the unbundled faculty role was to identify a framework for gathering costs. The unbundled roles can be separated into three types of activities. The first activity is the design and development of the online course. Rumble (2001) suggests that there is a clear division of labor between the activities associated with course development and the activities associated with the delivery of the course. Delivering the course is a second cost center. Interviews with distance education administrators at the university where this study was undertaken revealed a third center of activity, course maintenance.

Once the cost centers were identified, a second step was taken to identify the individuals and the actions taken by those individuals to support online course design and development, delivery, and maintenance. A course developer, course facilitator, and faculty member charged with course maintenance were interviewed to determine the activities associated with each unbundled faculty role.

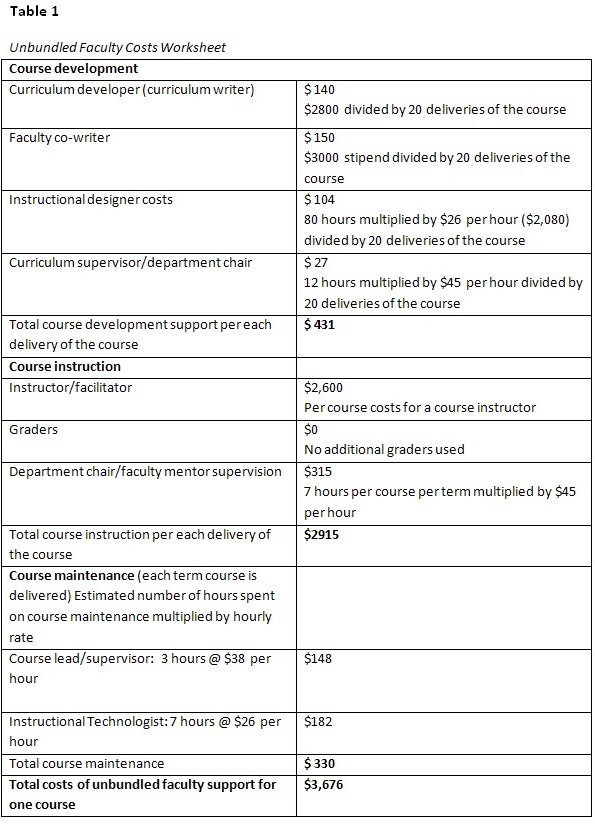

Data obtained from the interviews as well as from research into costing in distance learning was used to develop the unbundled faculty costs worksheet presented in Table 1. The worksheet provided a starting point for gathering and calculating the costs of the activities associated with the unbundled faculty role.

Online universities seem to follow three major models for curriculum development. A number of universities have developed departments devoted to curriculum development. Subject matter experts and curriculum developers with expertise in course design are hired in full-time positions to develop courses (Knowles & Kalata, 2007). Many universities follow the traditional model of paying a stipend to current faculty for course development, while some universities use part-time curriculum developers to create courses. Other universities use some type of blended model using current faculty and outside experts to develop courses. In this study, the university that provided costing data used a blended method, which paired a current faculty member with an external curriculum writer. The faculty member created learning objectives, identified learning materials including journal articles and textbooks, and identified the assessment methodology. The external curriculum writer developed the course assignments, the discussion threads, and the scoring rubrics for assignments.

The role of an instructional designer can vary depending on the university (Tantivivat & Allen, 2004). Some universities do not provide instructional design assistance to course developers. At other universities, the instructional designer assists with each step of course development. The university participating in this study provided instructional designer support to assist the faculty member with loading the course into the learning management system used by the university. The instructional designer ensured that the course provided ease of interaction and clarity to the student and made certain that there were no biases in the way the subject matter was presented.

During the course design process, a department chair or lead faculty member often provides assistance to the course designers. The individual in this role makes sure that the course meets university standards, ensures that the course is developed according to project deadlines, and reviews the course to ensure quality. In this study, a full-time faculty member provided support and supervision for the development of the course. The faculty member estimated the number of hours dedicated to supporting the course in this study.

Calculating the costs for individuals filling the unbundled faculty role required several different approaches to costing. The costs for individuals who worked for the university on a full-time basis were calculated by dividing the total amount of salary plus benefits by the number of hours in the yearly contract to arrive at a per hour cost. The per hour cost was then multiplied by the number of hours that the individual identified as spending in support of the course. Some individuals participating in the study were paid a flat fee for their contributions. The flat fees were easily allocated to the course activities.

For this study, data was gathered on the per class compensation for an online graduate business course. Compensation data was gathered on faculty members who had earned a terminal degree in their field (PhD, EdD, JD, or DBA) and who had three years teaching experience. The number of weeks per class ranged from six to ten weeks and the per class compensation ranged from a low of $1800 per class to a high of $4,000 per class with the average hovering around $2200 per class. The course instructors in the specific graduate course included in this study were paid $2600 to facilitate the class for six weeks.

Course maintenance costs were calculated as $330 based on interview data from the department chair and an instructional technologist. Course maintenance costs are the least identifiable costs in the unbundled faculty role. Course maintenance may be as simple as updating a web link in a course or as complex as revising the assignments. Course maintenance is ongoing and is not reflected in budgets except when major course revisions are scheduled.

After calculating the cost of unbundled faculty support for one course, the researchers examined how the cost of support compared to the costs of support for one class with a traditional faculty role. The National Center for Education Statistics reported that the average salary for an assistant professor was $55,300 (Knapp, 2009). Fringe benefits varied as a percentage of salary dependent upon the type of institution. For the purposes of this study, fringe benefits were estimated at 30% of salary (Employee Benefits Research Institute, 2009). Total compensation for an instructional faculty member was calculated at $71,890 for the purposes of this study. The National Center for Education Statistics also reports that instructional faculty, on average, support eight courses during the academic year (Knapp, 2007). Based on data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the faculty member’s total compensation was approximated at $8,986 for a single course.

Our study revealed a cost of $3,676 for the instructional support provided to a single course with the unbundled faculty model. At first glance, the unbundled faculty role seems significantly less expensive than the cost of a traditional faculty member’s course support at $8,986 per course. However, the investment on a per course basis may be skewed in favor of the unbundled faculty role due to limitations in calculating the number of hours that a faculty member devotes to activities outside of instruction, such as university service. Also, it is difficult to assign the amount of time actually devoted to course design and maintenance unless instructional support personnel are asked to keep a time log of activities by course. For the purposes of this study, time spent on administrative and university service activities by faculty was ignored.

Our study revealed that there are significant per course costs that are often underaccounted in university budgets as a result of the unbundled faculty model. The unaccounted costs in the course design phase include leadership and support provided by lead faculty and department chairs in coordinating the design, development, and implementation of new courses. Far easier to identify and quantify are the costs incurred during the instructional phase. Faculty salaries were clearly identified based on the course assignments. The missing costs in the instruction phase were activities around faculty supervision and training. Course maintenance activities were also difficult to identify and were often overlooked in calculating unbundled faculty costs.

Most university budgets consider course development costs as sunk costs and do not allocate the costs to each delivery of the course. The costs of department chair support and instructional designer support are also rarely allocated at the course level. Course development costs for the course studied were $431 per course delivered. These costs included the work of a curriculum writer, a faculty lead, an instructional designer, and a department chair. These costs may not be considered significant on a per course basis, but when calculated across a number of courses can represent a significant investment of financial resources for a university. With the traditional faculty model, a faculty member would be tasked with developing a new course. The faculty member may or may not receive additional compensation for course development work depending on institutional policies.

The costs for course instruction are the most recognized costs in the unbundled faculty role. Often, course costs in budgets are limited to the cost of course instruction. Again, the costs of providing supervision and training to adjunct instructors are either not reported or are underreported when considering the costs of delivering an online course. The adjunct faculty member’s salary at the institution studied was higher than an average adjunct salary but significantly less than the cost of a full-time faculty member.

At first glance, the data seem to indicate that the costs per course of the unbundled faculty role are lower than the cost per course of hiring traditional faculty. However, this study suggests that it is difficult to identify and assign costs for instructional activities in higher education, particularly when comparing the traditional faculty model with the unbundled faculty model.

Interviews with university administrators indicate that there is an understanding that hidden costs are incurred, but ferreting out the information is difficult given the structure of budgeting and recording costs in higher education. Rumble (2001) writes, “Decision-makers want to know how much something will cost, and whether they can afford it. They need this information to set a budget, to cost change, and to decide between two or more different options” (p.2). The need to identify costs is not diminished by the fact that costing is a difficult and messy process as the researchers learned in conducting this case study.

Completion of this study indicates a need for further research in several areas. The costing worksheet that was designed as part of this study needs to be further developed so that university administrators can easily identify costs with the unbundled faculty model. Further research needs to be undertaken to identify whether an activity based costing model could be used to develop more accurate cost calculations for activities associated with the unbundled faculty role. A number of questions remain unanswered, such as the costs associated with creating new departments within the university to support instruction. Also, questions around how much it costs a university to hire, train, and supervise instructors remain unanswered.

In conclusion, there is much work to be done in developing costing models for the unbundled faculty roles. This study addresses only minimally the hidden costs of the unbundled faculty role. Future studies examining these costs would need to include real-time recordkeeping of hours dedicated to course development, delivery, and maintenance for not only the instructor but also for the online coordinators, the faculty schedulers, the instructional design coordinators, the course evaluators, and the quality assurance personnel. As online courses continue to proliferate and scrutiny of higher education costs increases, university administrators need to identify the cost impact of the unbundled faculty role.

Allen, E., & Seaman, J. (2008). Staying the course. Babson Survey Research Group: The Sloan Consortium.

Brinkman, P.T. (2001). The economics of higher education: Focus on cost. In M. Middaugh (Ed.), Analyzing costs in higher education: What institutional researchers need to know (pp. 5-17). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Employee Benefits Research Institute. (2008). FAQs about benefits – general overview. Retrieved from http://www.ebri.org/publications/benfaq/index.cfm?fa=ovfaq1.

Fairweather, J. S. (1993). Faculty rewards reconsidered: The nature of tradeoffs. Change, 25, 44-47.

Feldman, K. A. (1987). Research productivity and scholarly accomplishment of college teachers as related to their instructional effectiveness: A review and exploration. Research in Higher Education, 26, 227-298.

Finkelstein, M.J., Frances C., Jewett, F.I., & Scholz, B.W. (2000). Dollars, distance, and online education: The new economics of college teaching and learning. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Granof, M.H., Platt, D.E, & Vaysman, I. (2000). Using activity based costing to manage more effectively. PricewaterhouseCoopers Endowment for the Business Government.

Hagerott, J., & Ferezan, J. (2003). Faculty roles unbundled - Franklin University. In G. Richards (Ed.), Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education 2003 (pp. 1306-1308). Chesapeake, VA: AACE. Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/12128.

Horngren, C.T., & Harrison, W.T. (2007). Accounting (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Hrabowski, F.A. III. (2004). Leadership for a new age: Higher education’s role in producing minority leaders. Liberal Education, (90).

Knowles, E., & Kalata, K. (2007). A model for enhancing online course development. Innovate, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info.

Knapp, L.G. (2008). Employees in postsecondary institutions, fall 2007, and salaries of full-time instructional faculty 200. Retrieved from National Center for Education Statistics website: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2009154.

Linsky, A. S., & Straus, M. (1975). Student evaluation, research productivity, and eminence of college faculty. Journal of Higher Education, 46, 89-102.

Ljosa, E. (1988). The boundaries of distance education. Journal of Distance Education, 3(1), 85-88.

Nagel, D. (2009, October 28). Most college students to take classes online by 2014. Campus Technology Online. Retrieved from http://campustechnology.com.

Neely, P.W. (2004). A cost study of various methods of delivering a university course (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Palloff, R.M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom. Danvers, MA: Jossey-Bass Publishing.

Rumble, G. (2001). The costs and costing of networked learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 75-96. Retrieved from http://php.auburn.edu/outreach/dl/pdfs/Costs_and_Costing_of_Networked_Learning.pdf.

Sammons , M.C., & Ruth, S. (2007, January). The invisible professor and the future of virtual faculty. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 4(1), 3-13.

Schuster, J.H., & Finkestein, M.J. (2006). The American faculty: The restructuring of academic work and careers. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Stratford, M. (2009, January 26). University set to slash budgets. The Cornell Daily Sun.

Tantivivat, E.M., & Allen, S.D. (2004, July). Instructional designers and faculty working together to design learning objects. Paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning. Madison, WI.

Trout, W. E. (1979). Unbundling instruction: Opportunity for community colleges. Peabody Journal of Education, 56(4), 253-259.

Wang, W. K. S. (1975). The unbundling of higher education. Duke Law Journal, 1, 53-90.

Wechsler, H. S. (2004). Overview. The NEA 2004 almanac of higher education. Washington, DC, NEA. Retrieved from http://www.nea.org/assets/img/PubAlmanac/ALM_04_01.pdf.

Winston, G.C. (1988, December 14). Economic research shows that higher education is not just another business. The Chronicle of Higher Education.