This article introduces the work of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and describes its interest in the application of distance learning strategies pertinent to the challenges of food security and rural development around the world. The article briefly reviews pertinent examples of distance learning, both from the experience of FAO and elsewhere, and summarises a complex debate about the potential of distance learning in developing countries. The paper elaborates five practical suggestions for applying distance learning strategies to the challenges of food security and rural development. The purpose of publishing this article is both to disseminate our ideas about distance learning to interested professional and scholarly audiences around the world, and to seek feedback from those audiences.

The mission of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is to help build a food-secure world for present and future generations. The achievement of this mission depends upon the capacities and actions of a globally distributed set of individuals, organisations and communities. While a range of factors determines such capacities and actions, education and learning are widely recognised as important components of development. Since its inception, FAO has played a significant role in producing, managing and disseminating knowledge for processes of education and learning of importance to food security around the world. The Organization has adopted five corporate strategies to guide its activities over the next fifteen years:

1. Contributing to the eradication of food insecurity and rural poverty.

2. Promoting, developing and reinforcing policy and regulatory frameworks for food, agriculture, fisheries and forestry.

3. Creating sustainable increases in the supply and availability of food and other products from crop, livestock, fisheries and forestry sectors.

4. Supporting conservation, improvement and sustainable use of natural resources for food and agriculture.

5. Improving decision-making through the provision of information and assessments and fostering of knowledge management for food and agriculture.

The accomplishment of this strategic agenda will necessarily involve processes of education and learning. Over the past decade, there has been a resurgence of international interest in distance learning as a potentially useful strategy for addressing human development issues. This resurgence has been rooted, in part, in the evolution of new information and communications technologies, and, in part, in the improvement of pedagogical and administrative models for facilitating learning at a distance. United Nations agencies have contributed to the resurgence of international interest in distance learning. UNESCO (1997) has issued a policy document encouraging the use of distance learning, at all levels of educational systems, for purposes of development. The World Bank (1999) promotes “innovative delivery” as one of its global priorities for the educational sector. The World Health Organization (1998) promotes the use of “telematics,” including distance health education, in support of its Health-for-All agenda. Both UNESCO ( http://www.unesco.org/education/e_learning/index.html ) and the World Bank ( http://www1.worldbank.org/disted ) host Internet sites providing information to promote the appropriate use of distance learning. In addition to such policy advocacy and information dissemination functions, many United Nations agencies have employed distance learning strategies through their own programmatic interventions, and provided financial or technical assistance to a multitude of national and regional distance learning projects in developing countries.

FAO has accumulated significant experiences in the field of distance learning. Since the 1960s, FAO has contributed to the development of rural radio as a medium of information exchange and learning in many African countries. More recently, FAO has used distance learning strategies both for formal education and information dissemination purposes. One example is the ongoing collaboration between FAO and the REDCAPA network. REDCAPA is the “Network of Institutions Dedicated to Teaching Agricultural and Rural Development Policies for Latin America and the Caribbean” (Red de Instituciones Vinculadas a la Capacitacion en Economia y Políticas Agricolas en America Latina y el Caribe). REDCAPA was founded in 1993 through the initiative of the FAO Policy Assistance Division in collaboration with organisations from eleven Latin American and Caribbean countries, and financial support from the government of Italy. The REDCAPA network currently involves 66 universities and other organisations concerned with teaching agricultural economics and policies and sustainable rural development ( http://www.redcapa.org.br ) . Most members are from the region, although several European and American universities take part. REDCAPA’s main objectives are to contribute to the improvement of teaching and research in agricultural economics, rural development and the environment, support institution building, and improve national and international cooperation among its members. Among the various activities implemented to accomplish these objectives, the network coordinates regular distance learning courses on pertinent topics. In addition to its role in the establishment of REDCAPA, FAO has assisted the network financially, and provided training materials and direct support for a number of distance learning courses offered in the areas of food security policy, macroeconomics and gender analysis.

The Information Network on Post-harvest Operations (INPh O) is a second example of FAO experience with distance learning. INPh O is managed and facilitated by the Agro-Industries and Post-Harvest Management Service on behalf of a range of international partners. INPh O provides three basic services ( http://www.fao.org/inpho ) :

1. Information and data bases concerned with a range of post-harvest issues (e.g., storage, transportation, processing, marketing and food safety).

2. Interactive communication services connecting users with one another and with resource people.

3. Links to other electronic sources of post-harvest information.

INPh O’s long-term objective is to contribute to food security and rural development by enhancing post-production systems around the world. The more immediate objectives are to disseminate selected information in a user-friendly way, to facilitate communication between post-harvest actors, and to support decision makers. INPh O’s targeted beneficiaries are small farmers, small enterprises and consumers. These beneficiaries are influenced through intermediary target groups including governmental institutions, research centres, universities, schools, non-governmental organisations, extension workers and entrepreneurs. INPh O was developed in 1997, became operational in 1998, and has grown into an important network for information dissemination and learning. The INPh O website is a busy one, with over 8,000 hits per day (and 800 user sessions per day) recorded in October 2000. In addition to the website, INPh O disseminates CD-Rom versions of its information services (some 8,000 copies have been produced to date). The interactive communications services involve a question and answer service on post-harvest issues, as well as a structure for moderated and non-moderated email conferences.

In addition to these existing initiatives, FAO is developing several projects with distance learning components. The Fisheries Industries Division is developing a series of three correspondence courses aimed at building local technical knowledge and management skills for sustainable artisan fisheries. The Outreach Programme of the World Agricultural Information Centre (WAICENT) is launching a CDROM-based Information Management Resource Kit to share tools and methodologies with member nations to build their capacity to manage agricultural information.

In the context of its own experiences and growing international interest in the field, FAO is exploring how distance learning could be most usefully applied to the achievement of its mission. This paper represents an important step in such an exploration. It summarises various arguments that have been made concerning the potential of distance learning in developing countries, and then makes five practical suggestions for applying distance learning strategies to the challenges of food security and rural development. The purpose of publishing this article is both to disseminate our ideas about distance learning to interested professional and scholarly audiences around the world, and to seek feedback from those audiences.

The use of distance learning strategies in developing countries is by no means novel. The potential connections between distance learning and development processes have been recognised for decades, as the following passage from Kabwasa and Kaunda (1973, p. 8) demonstrates:

Correspondence education has yet to make an impact in Africa. We feel it is our responsibility to give it as much publicity as we can, so that our people know its potentialities and possibilities, and how they can go about making greater use of it in the development of our continent.

In a recent overview, Hilary Perraton (2000) organises distance learning experiences in developing countries into four categories: 1) non-formal and adult education; 2) primary and secondary schooling; 3) teacher training; and 4) higher education. He provides numerous examples to indicate that countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America have had significant experience with distance learning since at least the 1960s. The following four examples of distance learning programmes related to agriculture have all reached substantial numbers of learners in developing countries, and have been sustained for at least a decade.

First, since the 1960s, “INADES-formation” (Institut Africain pour le développement économique et social) has provided non-formal distance learning opportunities to tens of thousands of farmers, extension agents and other agents of rural development in Africa (Dodds, 1999; Perraton, 2000). Courses for farmers include those on agricultural production and animal husbandry, as well as those on basic mathematics, management, marketing, credit and cooperatives. For extension agents and other development workers, additional courses are available on communication, extension methods, management and the rural economy. The delivery strategy for “INADES-formation” courses is a combination of print-based correspondence packages with local study groups and tutorial support.

Second, since 1973, the G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology has offered a Correspondence Course Programme to farmers and rural youth in Uttar Pradesh, India (M.P. Singh, 1992, 1999). About 500 learners each year select four courses from a list of seventeen options (fourteen concern the cultivation of particular crops, and one each concern dairy production, insecticide use and fertiliser use). The Programme’s delivery strategy is print-based correspondence. Each course comprises five or six lessons, written in elementary Hindi. Course scheduling is timed to coincide with the seasonal production of the various crops under study. The University has twenty District Extension Centres students may contact for personalised guidance and study support. Non-credit certificates are issued to all students passing end of term examinations in each course.

Third, since 1986, the Women’s Secondary Education Programme of Allama Iqbal Open University has been providing rural women in Pakistan with courses to meet secondary school equivalency and to increase income generating opportunities through building practical skills (Batool and Bakker, 1997). The range of practical courses includes Selling of Home Made Products, Garment Making, Poultry Farming, Food and Nutrition, First Aid, Home and Farm Operations, and General Home Economics. The content of all courses has been designed to reflect the priorities, needs, and prior experiences of adult rural women. All courses are delivered through print-based correspondence methods, and learners receive tutorial support through local study centres. As of 1996, the Programme enrolled about 4,000 learners per semester.

Fourth, since 1988, Wye College of the University of London has delivered an External Programme that uses distance learning to provide learners around the world with opportunities for graduate study in agricultural development (Bryson and Hakimian, 1992; Pearce and Sharrock, 2000). Currently, over 1,000 learners from over 100 countries are enrolled in a range of programmes rooted in agricultural and environmental economics, management and planning. The Programme initially used traditional correspondence methods, and has recently added an Internet-based learning system for delivery of learning materials, tutorial support, assignment submission and feedback, and opportunities for learner-learner interaction.

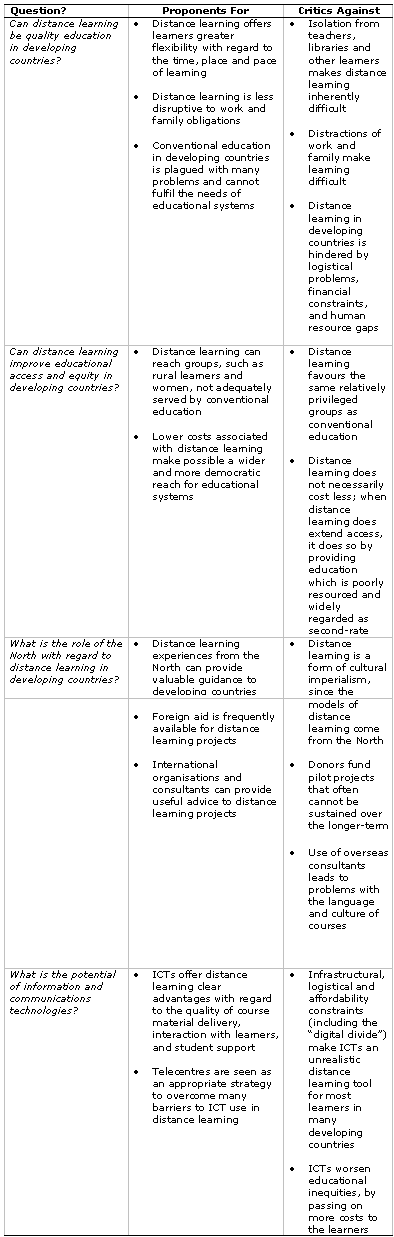

The fact that distance learning is an established form of educational delivery in many developing countries does not mean that distance learning is necessarily an effective tool in development efforts. Understanding the past influence and future potential of distance learning for challenges related to food security and rural development is not an easy task. Substantial literature has emerged that either describes or evaluates the past experiences and future potential of distance learning in developing countries (Arger, 1985, 1990; Bilham and Gilmour, 1995; Daniel, 1990; Dodds, 1996; Farrell, 1999; Guy, 1991; McAnany et al., 1983; Perraton, 2000; Shrestha, 1997a, 1997b; UNESCO, 1997; Young et al., 1980) or in particular regions such as Africa (Chale and Michaud, 1997; Fillip, 2000; John, 1996a, 1996b, Saint, 1999; UNESCO 1990, 1991, 1995). In these and other publications, a range of general claims has been made about the strengths and limitations of distance learning in developing countries. Many of these claims contradict one another. Table 1 indicates that there is no overall consensus about distance learning in developing countries.

Table 1. The Case For and Against Distance Learning in Developing Countries

What can we conclude about distance learning as a means to promote rural development and food security? With regard to its track record, distance learning has had both successes and failures in developing countries. The lengthy list of problems and disappointments identified by critics of distance learning would lead to a pessimistic conclusion, unless one recognises that conventional alternatives in developing countries have also, at times, been unable to provide adequate levels of educational access, equity and quality (Perraton, 2000, p. 198). With regard to its future potential, distance learning seems to be a promising response to certain educational challenges, but it should not be seen as a panacea. Many institutions in developing countries are steadily increasing their capacity to engage in distance learning, and appropriate technological innovations are being used in many contexts.

The appropriateness and effectiveness of distance learning depends on why, how, and how well it is designed and delivered. Distance learning initiatives should be undertaken for appropriate reasons, and in a manner that is suitable to the stakeholders of the initiative. Organisations undertaking distance learning initiatives must have the capacity to do so, and must invest or obtain the necessary resources in order to do it well.

The claims listed in Table 1 are rooted in specific experiences of distance learning in contexts pertinent to food security and rural development in developing countries. Some of these experiences are from within FAO, but most are described in the literature cited in the last section of this article. By analysing these past experiences, it is possible to distil important lessons that have been learned. Paying attention to those lessons is a first step in creating an approach to distance learning that would enable FAO to act appropriately in this challenging field.

Meacham (1993, p. 227) suggests that distance learning initiatives have been undertaken in developing countries for political or commercial purposes: “Apart from the obvious purpose of teaching more people more effectively, distance learning systems have been used to impress donors, placate ministers, justify consultancies, and even sell technologies.” In the context of the contemporary development of new information and communication technologies, there is a danger that distance learning initiatives can be driven by the availability of innovative technologies (and the desire to be seen using them), rather than by the educational needs of individuals and communities. Fillip (2000, p. 42) argues:

Starting with the real needs of communities cannot be stressed enough. There is a strong tendency in the donor community to start with the technology rather than with the needs of the community and to ask the wrong questions. The important question is not “Can the Internet be used to provide distance learning to communities?” The important question is “What is the most appropriate, cost-effective and sustainable way to address the educational needs of communities?”

The FAO undertakes distance learning initiatives in support of its strategic objectives. In the struggle for food security and rural development around the world, distance learning should be conceptualised as a means to an end, and not an end in itself.

There is no universally appropriate model for designing and delivering distance learning initiatives. The potential target audiences for distance learning initiatives in which FAO might become involved is broad indeed, ranging from agricultural producers and marginalised rural populations, to relatively privileged urban professionals such as policy makers and information managers. It is essential that the form of distance learning selected be appropriate to the particular context in which it is being applied.

In a study of South Africa, Geidt (1996) identifies significant practical challenges that indicate adult basic education at a distance cannot function on an open university model adopted from the United Kingdom. Communities most in need of adult basic education provision in South Africa tend to have the following characteristics: slow and unreliable postal systems, few and unreliable telephones, lack of access to television, lack of electrification, poor road conditions, few and inadequate libraries, and inadequate school or other public facilities for studying. In addition to these infrastructure challenges, Geidt (1996, pp. 16-19) identifies several social and economic characteristics of disadvantaged communities in South Africa that make an open university style of distance learning unlikely to succeed. First, many people live in crowded housing conditions, and as a result learners do not have easy access to appropriate conditions in which to study. Second, written texts are not commonly used in day-to-day life; as a result learners are not accustomed to critically interpreting textual messages and constructing written responses. Third, previous school experiences of most learners are of rote learning, and as a result learners must make a difficult transition to become independent and critical learners. Fourth, there is tremendous cultural and linguistic diversity; as a result, many learners may have difficulty with the language and culture of standardised instructional materials. Geidt (1996, pp. 14-15) concludes that distance learning can only be effective when its delivery system and curriculum are appropriately matched to the social and political context of the learners. In the case of adult basic education in South Africa, Geidt (1996, pp. 19-20) suggests that a substantial component of face-to-face support is essential, and identifies several means through which such support could be provided (e.g., community-based tutors, community learning centres, and regional study centres).

One model of distance learning cannot be appropriate to all potential target groups of interest to FAO. Distance learning models and practices must be adapted to the social, cultural, economic and political circumstances of learners and their environment. As with other forms of educational activity, it is important to integrate gender analysis into the planning and implementation of distance learning initiatives.

One disturbing tendency in the history of distance learning in developing countries is the large number of initiatives that demonstrate significant learning outcomes and programmatic success during pilot projects, but are not sustained or replicated on a larger scale after the pilot project is complete and donor funding is withdrawn. While the lack of sustainability and scalability may reflect a number of variables, it is frequently related to the use of inappropriate delivery strategies. The failure of many educational television projects in developing countries in the 1970s and 1980s is an example of what Meacham (1993, p. 227) calls “technological overkill” in distance learning. This phenomenon refers to the use of expensive and complex delivery strategies when inexpensive and simple alternatives could be pedagogically effective. Fillip (2000, p. 25) argues that when it comes to choosing technologies for distance education “ . . . .it is essential to take a careful look at the level of infrastructure that the target populations have access to, and the extent to which the same target populations can afford to make use of that infrastructure for educational purposes.” When donors have tried to provide a communication infrastructure for distance learning programmes, such programmes have very rarely been sustainable. Given challenges with the costs and servicing of equipment, educational projects should use technologies that have already been established through entertainment and commercial sectors (Perraton and Creed, 2000, p. 17). With regard to sustainable technology choices, Dodds’ (1972, p. 46) conclusion from nearly thirty years ago is still pertinent: “The installation of new and glamorous media at great expense may be less effective than the careful integration of existing resources.”

The question of technologies and delivery strategy is related to the more general question of the cost-effectiveness of distance learning. Distance learning is sometimes presented as universally more cost-effective than conventional education. Past experiences in both developed and developing countries indicate that this is not necessarily the case. Distance learning has the potential to be, but is not necessarily, more cost-effective than conventional education (Perraton, 2000, pp. 136-138; Rumble, 1997, pp. 203-204; Rumble, 1999, p. 133; UNESCO, 1997, pp. 33-34). A range of factors that contribute to substantial cost differences between different distance learning initiatives are: numbers of learners enrolled, mixture of communication technologies, media and learning materials, degree of learner support and interaction, salaries and employment conditions of distance learning staff, production standards, and institutional working practices and overhead costs. A general conclusion that can be drawn is that distance learning tends to be more economically attractive at higher levels of education (Perraton, 2000, p. 196). This is because the costs of distance learning are relatively similar at all levels, whereas the costs per student of conventional education are higher at higher levels.

Distance learning is not simply an inexpensive alternative to other forms of educational programming or field interventions. In some cases, distance learning may provide a cost-effective means of reaching target groups of learners, but in other cases conventional face-to-face contact may be more cost-effective. The assumption that distance learning is a low-cost alternative can undermine the quality and impact of distance learning programmes by systematically depriving them of necessary resources.

In the field of food security, organisations should not endeavour to establish independent systems of communication for the delivery of distance learning initiatives. Rather, in each specific case, delivery strategies for distance learning initiatives should be developed according to the communication infrastructure that is currently available, reliable and affordable to the learners who will take part in the initiative. This does not mean that Internet-based delivery strategies must be universally rejected in favour of simpler alternatives such as print and radio. It does mean that the pedagogical strengths of any potential delivery strategy must be carefully assessed according to the practical constraints facing each group of learners. Some target audiences will have ready access to computers and the Internet, while others will not even have electrical power or reliable telephone service.

Many of the problems with previous distance learning programmes in developing countries relate to a lack of participation on the part of those individuals and communities who were supposedly the beneficiaries in the design and delivery of the programmes. Guy (1991, p. 169) argues that an appropriate:

. . . conception of distance education would require a focus on programs in which participants have control over not only what is taught, but how and where distance education takes place. It is dependent on the participation of people, who through participatory planning and action, to develop a deeper understanding of their lives and the structures which surround them in time and space.

The need for participatory and empowering educational practice has been identified by FAO in its work in the fields of agricultural education, extension and communication for development. FAO (1999) has published a guide entitled Participatory Curriculum Development in Agricultural Education. The guide (FAO, 1999, pp. 70-73) categorises general groups of stakeholders in curriculum development processes as the “insiders” (i.e., leaders with training organisations, teachers, students, producers of educational materials), and the “outsiders” (i.e., policy-makers, politicians, educational administrators, educational experts, employers, professional bodies, clients, funders, parents, past students and special interest groups). Early in the analysis of a potential educational intervention, it is important to identify the stakeholders, understand those stakeholders’ diverse interests, and develop a process through which such stakeholders will be represented in the planning, implementation and evaluation of the intervention. The process of identifying, understanding and involving stakeholders help ensure that distance learning initiatives are undertaken for the right reasons, are sensitive to the contexts of learners and their environments, and are sustainable.

The substantial number and range of distance learning experiences accumulated in developing countries can help FAO craft pedagogical and administrative models that avoid replicating some of the fundamental mistakes that have been made in the past. While ideal models and practices have yet to be developed, practitioners and scholars in both the Northern and Southern hemispheres have done much to critically examine distance learning and make its application more appropriate to diverse circumstances around the world. Over the past decade, the practice of distance learning in both developed and developing countries has evolved substantially. In developing countries, Perraton (2000, p. 197) suggests:

The best-run programmes are probably better, more effective, and more interesting for their students than they were a generation back. There is a reasonable consensus on good practice, which will include using a combination of media, ensuring that there is effective tutoring and student support, having an efficient administrative system, and developing clear and well-produced teaching material.

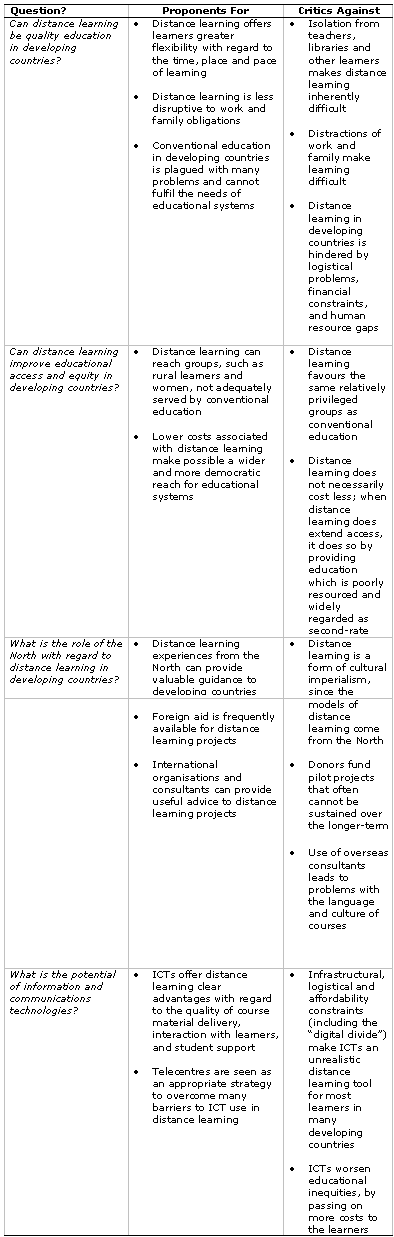

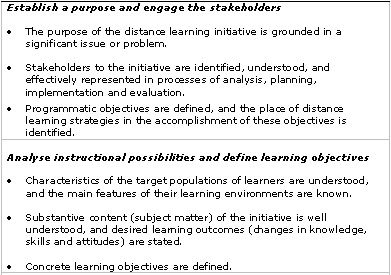

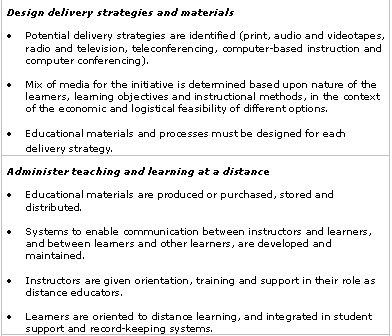

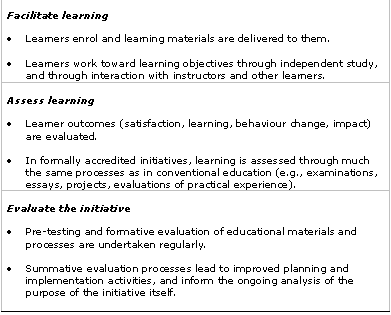

In developed countries, technological change has led to what Garrison (1997) calls the “post-industrial age” of distance education. In higher education, mainstream research universities in the Northern hemisphere are creating models of “distributed education” and “little distance education” as they use networked learning environments that blend distance education with face-to-face instruction (Garrison and Anderson, 1999). There is now increasing sensitivity to gender issues as important variables in the practice of distance education (Burge, 1998). Any organisation contemplating the application of distance learning strategies to the challenges of food security and rural development should be aware of the pedagogical innovations of the past decade. Table 2 identifies a basic outline of best practices in distance learning.

Table 2. Best Practices in Distance Learning

The Food and Agriculture Organisation can be an international catalyst for the learning of a diverse and globally distributed set of individuals, organisations and communities whose capacities and actions influence the achievement of food security and rural development. In collaboration with a wide range of partners, and in conjunction with other methods of intervention, the Organisation can employ innovative and appropriate distance learning methods to accomplish its strategic objectives.

Arger, G. (1985). Promise and Reality: A critical analysis of the literature available in Australia on distance education in the Third World. ERIC document ED 284 022.

Arger, G. (1990). Distance education in the third world: Critical analysis on the promise and reality. Open Learning, 5(2), 9 – 18.

Batool, S. N., and Bakker, S. (1997). Step by step towards success. Open Learning, 12(1), 3 – 11.

Bilham, T., and Gilmour, R. (1995). Distance Education in Engineering for Developing Countries. London: Overseas Development Administration.

Bryson, J., and Hakimian, H. (1992). The Wye College External Programme and Third World agriculture. In G. Rumble and J. Oliveira (Eds.) Vocational Education at a Distance: International perspectives. (p. 102-113) London: Kogan Page in association with the International Labour Office.

Burge, E. (1998). Gender in distance education. In C. C. Gibson (Ed.) Distance Learners in Higher Education: Institutional responses for quality outcomes (p. 25-45) Madison, WI.: Atwood Publishing.

Chale, E. M., and Michaud, P. (1997). Distance Learning for Change in Africa: A case study of Senegal and Kenya policy and research prospects for the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Retrieved August 27, 2001 from: http://www.idrc.ca/acacia/03230/04-dlear/index.html

Daniel, J. (1990). Distance education and developing countries. In M. Croft et al. (Eds.) Distance Education: Development and Access. (p. 101-110) Papers in English prepared for the Fifteenth ICDE World Conference held in Caracas, Venezuela, November.

Dodds, T. (1972). Multi-media Approaches to Rural Education. Cambridge: International Extension College.

Dodds, T. (1996a). The Use of Distance Education in Non-Formal Education. Vancouver, Commonwealth of Learning.

Dodds, T. (1999). Non-Formal and Adult Basic Education through Open and Distance Learning in Africa: Developments in the Nineties towards Education for All. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning.

FAO (1999). Participatory Curriculum Development in Agricultural Education: A Training Guide. Rome: FAO.

Fillip, B. (2000). Distance Education in Africa: New technologies and new opportunities. Washington: Japan International Cooperation Agency.

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Computer conferencing: the post-industrial age of distance education. Open Learning, 12(3), 3 – 11.

Garrison, D. R., and Anderson, T. (1999). Avoiding the industrialization of research universities: Big and little distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 13(2), 48 – 63.

Geidt, J. (1996). Distance education into group areas won’t go? Open Learning 11(1), 12 – 21.

Guy, R. (1991). Distance education and the developing world: Colonisation, collaboration and control. In Terry Evans and Bruce King (Eds.) Beyond the text: Contemporary writings on distance education. (p. 152-175) Geelong: Deakin University Press.

John, M. (1996a). Distance education in sub-Saharan Africa: the promise vs the struggle: part 1. Open Learning, 11(2), 3 – 12.

John, M. (1996b). Distance Education in Sub-Saharan Africa: The promise vs the struggle – Part 2. Open Learning, 11(3), 21 – 30.

Kabwasa, A., and Kaunda, M. (1973). Correspondence Education in Africa. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McAnany, E., Oliviera, J. B., Orivel, F., and Stone, J. (1983). Distance Education: Evaluating New Approaches in Education for Developing Countries. Evaluation in Education, 6, 289 – 376.

Meacham, D. (1993). Quality and context in the developing world: fitness for purpose, whose purpose? In T. Nunan (Ed.) Distance Education Futures. (p. 221-239) Adelaide: University of South Australia.

Pearce, R., and Sharrock, G. (2000). The Changing face of distance learning. Staff and Educational Development International, 4(1), 29 – 36.

Perraton, H. (2000). Open and Distance Learning in the Developing World. London: Routledge.

Perraton, H., and Creed, C. (2000). Applying new technologies and cost-effective delivery systems in basic education. In Education for All 2000 Assessment: Thematic Studies. (p. 14-18) Paris: UNESCO.

Rumble, G. (1985). Distance education in Latin America: Models for the 1980s. Distance Education, 6(2), 248 – 255.

Rumble, G. (1997). The Costs and Economics of Open and Distance Learning. London: Kogan Page.

Saint, W. (1999). Tertiary Distance Education and Technology in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington: World Bank, ADEA Working Group on Higher Education.

Shrestha, G. (1997a). Distance Education in Developing Countries. Retrieved August 27, 2001 from: http://www.undp.org/info21/public/distance/pb-dis.html

Shrestha, G. (1997b). A Review of Case Studies Related to Distance Education in Developing Countries. Retrieved August 27, 2001 from: http://www.undp.org/info21/public/review/pb-rev.html

Singh, M. P. (1992). Experiences from and impact of an innovative correspondence course-based distance education programme in agriculture. Indian Journal of Open Learning, 1(1), 11 – 13.

Singh, M. P. (1999). Professional correspondence courses of University of Agriculture and Technology. In S. Panda (Ed.) Open and Distance Education: Policies, Practices and Quality Concerns. (p. 163-176) New Delhi: Aravali Books International.

UNESCO (1990). Priority Africa. Final Report of the Seminar on Distance Education in Africa held in Arusha, Tanzania from 24 to 28 September, 1990. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (1991). Africa: A Survey of Distance Education 1991. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (1995). Rapport Final: Séminaire Sous-Regional sur l’Education á Distance. Paris: UNESCO, Secteur de l’Education, Priorité Afrique.

UNESCO (1997). Open and Distance Learning: Prospects and Policy Considerations. Paris: UNESCO.

WHO (1998). A Health Telematics Policy in support of WHO’s Health-for-All Strategy for Global Health Development. Geneva: WHO.

World Bank (1999). Education Sector Strategy. Washington: World Bank.