Peter Bergström

Umeå University, Sweden

This article reports on a study that was carried out in autumn 2007 with students in a professional nurse education distance course at a Swedish university. The study aimed to develop a greater understanding of the student-teacher relationship based on research questions addressing the teachers’ role, the learning process, and the assessment process in traditional approaches to teaching and learning. A didactical design was adopted, focusing on three learning outcomes in three phases. In each of the three phases, these learning outcomes were assessed by each student documenting his/her knowledge at the beginning, middle, and end of the course. Data was collected via in-depth interviews with students (n = 14) and through a questionnaire (n = 40) and was analysed using an inductive thematic analysis of the material. The results indicate a student-teacher relationship involving ambiguity and complexity in relation to the degree of teacher direction as being teacher-centred or learner-centred and also in relation to the learning process as being reproductive or productive. The interpretation of the results shows diverse aspects of the student-teacher relationship arising from students’ beliefs about teaching, learning, and assessment and, in particular, process-based assessment. The locus of control involves the teachers’ role, the learning process, and the assessment process, which illuminates different perspectives of power relations in the student-teacher relationship.

Keywords: Process-based assessment; power relations; learning process; assessment process; teacher direction

Students can access education today without leaving their hometown and family, making it easier to increase the overall level of education of citizens in society. The use of contemporary technologies in education creates the possibility of changed roles for both students and teachers. In this evolving paradigm, new skills are necessary for managing students’ learning and their achievements. The European Union has identified eight key competencies (The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2006). The goals of the fifth key competency, learning to learn, are to make the learner aware of his/her learning process, to develop the learner’s skills to solve problems in the learning situation, and to build on the learner’s existing knowledge, gained from other educational experiences at work or in everyday life.

Both in face-to-face learning and distance education, there are perspectives of control in the student-teacher relationship. When entering a distance course, most students will have experienced traditional teaching and learning, which is understood as the knowledge transfer metaphor (Säljö, 2000), mediated by desk teaching. Within this tradition, the students are characterised as having a passive role in the student-teacher relationship. Garrison and Anderson (2003) argue that e-learning provides a different learning experience but that much of the existing knowledge on the student-teacher relationship rests upon classroom teaching. It is plausible to believe that this interaction between new and old experiences creates confusion regarding control. Garrison and Baynton (1987) explore the notion of control as the balance between independence, power, and support. In the student-teacher relationship, independence is simply freedom in the students’ learning; power deals with the question of responsibility for one’s learning; and support grows from the role of the teacher. Thus, confusion can arise for both teachers and students when control shifts between the actors. This paper reports on a study that aims to understand the student-teacher relationship in the context of process-based assessment for learning (Black & Wiliam, 1998). The notion of process-based assessment is understood from cycles of reflections and formative assessment. The context for the study is a professional distance education course on the subject of child health care in a nurse education programme. Limited generalisations are warranted with regard to the particular context of this study and to the group of students of inquiry. The research questions addressed students’ expectations and beliefs in relation to teaching and learning:

In practice, there are a variety of methods to document the learning process, including reflective journals, learning journals, or process diaries. The promotion of critical thinking is a central aspect of all these methods (Harris, 2007; Langer, 2002; Thorpe, 2004). Thorpe (2004) highlights the move from a routine practice to a reflective professional practice. This movement fosters a student-centred approach and active learning in which students at different levels arrive at new insights into the practice or subject at hand. Such a shift in practice reflects a student-teacher relationship in which the teachers guide students with the support of formative feedback (Bergström & Granberg, 2007). However, when students are not accustomed to employing these reflective methods, difficulties can arise, as illuminated in the study by Langer (2002), which highlights the problems that students can have in understanding the purpose of a learning journal.

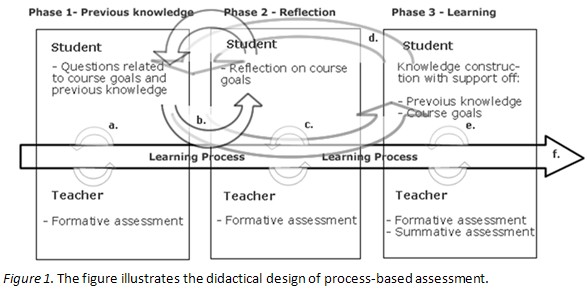

The figure below illustrates the didactical design for a course of study that takes its starting point in the three phases aimed at covering and capturing the students’ learning process during the semester. In the Swedish language, the term process refers to a course of events that is intended to change and develop something (SAOL, 2009).

Phase 1 establishes the starting point as the beginning of the course. In this phase, students describe previous knowledge from the perspective of their previous life, work, and study experiences, upon which the teacher gives feedback (a). In the middle of the course (phase 2), students reflect upon their knowledge in relation to their previous knowledge and the learning outcomes (b), which is followed up with teacher feedback (c). When students finish the course (phase 3), they summarise their learning in relation to their previous knowledge and the learning outcomes (d). The teacher provides feedback on the students’ texts and makes a final judgement (e). As with reflective learning journals, students focus on the documentation of their experiences, events, and concepts, and over a period of time they gain self-awareness and insight into their learning (Thorpe, 2004), which constitutes the learning process (f). In this study, the students had the support of a learning management system (LMS) and a web-based videoconference system (Marratech). Recording of the outcomes of the process-based assessment was achieved by using document files stored in the LMS.

The teachers used a template developed in a teacher education programme. In the first phase, the students were asked to describe their previous experiences from work, school, and life, and this was followed by three open questions from the perspective of three learning outcomes; for example, “Analyse lifestyle and risk of accidents among children and youths, and carry through and evaluate necessary actions.” In the second phase, the students found eight points for reflection from the perspective of the assignments in the course (e.g., the care of children), followed by four points of reflection upon literature, lectures, and scientific articles. In the third phase, the students took their starting point from the learning outcomes by developing three key concepts in their own words together with an analysis of their learning during the course of study. Furthermore, the teacher asked the students for future reflections in phase three.

The study focused on a mixed group of district and child nurse students attending a child health care course in a specialist nurse program at a university in Sweden in autumn 2007. The course was a distance course at a 50% pace, with two mandatory face-to-face meetings at the start of the course and at the end of the course. Between the meetings, the students worked in study groups at a distance, supported by videoconferencing and the use of the LMS. Each week the teachers held seminars through the use of videoconferencing. Furthermore, as a course requirement, the students underwent practical nurse training at child health care centres and in school health care. As well, the students attended another course at a 50% pace, fulfilling the 100% study pace. At the start of the course, students were asked to answer a questionnaire about their previous educational backgrounds and their positive and negative experiences of being assessed. From the questionnaire a convenience selection was used in which 10 out of 42 students volunteered to participate in the research study. At the outset, students agreed to a statement of research ethics. This followed the guidelines from both the Swedish Research Council (2001) and the University and addressed the aspects of beneficence, nonmalfeasance, informed consent, and confidentiality/anonymity. Before the study began, two students dropped out. The eight students were females between 25 and 42 years of age, with 1.5 to 20 years of work experience. The informants had limited experience with distance education, particularly ICT-supported distance education.

The teachers who decided to use process-based assessment were keen and enthusiastic about starting. Neither the teachers nor the students had prior experience of process-based assessment. Accordingly, the teachers took as their starting point the work of Bergström & Granberg (2007) by adopting a template that was modified for their particular needs. At the start of the course, the teachers introduced the students to process-based assessment during the mandatory meeting by giving a lecture for 30 minutes in which the pedagogical approach was briefly explained and the students had the opportunity to ask questions. The slides from the lecture were accessible in the LMS during the course.

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with the eight students, five weeks after the start of the course, and focused on the first phase of the process-based assessment. The interviews were conducted by phone and, when possible, face-to-face. A follow-up interview was completed with the six remaining students, three weeks after the course was completed, and was focused on the second and third phases of the process-based assessment. The student interviews were based on themes from all three phases. The two sets of interviews followed a similar structure, which aimed to capture the students’ experiences in each phase from the perspective of the students’ feelings, the character and nuances of process-based assessment, and the students’ expectations of the teachers and of process-based assessment. The interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed, and notes were taken during the interviews. The recorded material from the interviews amounted to 15.5 hours.

Thematic analysis is a process used for analysing qualitative data. This process is understood from the two perspectives of “seeing” and “seeing as” (Boyatzis, 1998). To see something means to find patterns in the data that begin with a coding procedure; whereas, to see as focuses on the interpretation of the analysis by bringing parts together. A starting point in the data was taken, and the coding procedure was derived inductively.

The qualitative process was understood from different steps of reflections and interpretations by using an inductive approach. However, Coffey and Atkinson (1996) describe clues to look for in qualitative data in support of inductive analysis of the material, including episodes, comparisons, and contrastive thinking in the statements. In line with Boyatzis’ (1998) views on inductive thematic analysis, the coding procedure started by reducing the raw information into written outlines of each unit of text. The information was interpreted in terms of what the interviewee was explicitly or implicitly saying. From the units of text, the process of “seeing” started by identifying descriptive themes (Wolcott, 2001). As the purpose of my research was to understand process-based assessment, taking it a step further was necessary. This step moved from the descriptive level to a higher analytical level in order to investigate what underpinned process-based assessment. The higher level of “seeing as” involved a process of interpreting the themes in relation to other themes and to theory.

The tools for understanding didactical design through the analysis of student interviews are based on a theoretical framework that has been developed as part of this study. In the analysis, Moore’s (2007) theory on transactional distance was used to conceptualise the degree of teacher direction, while Illeris’ theory (2009) was necessary for conceptualising the learning process. By combining the theoretical perspectives of Moore and Illeris it was possible to illuminate how students move between different approaches to learning. Bernstein’s (2000) concepts of strong and weak classification and framing were used to interpret what underpins the context of process-based assessment, which supported an understanding of the student-teacher relationship.

The theory of transactional distance (Moore, 2007) addresses the teacher-student relationship in light of the degree of teacher direction. Transactional distance is seen as a relative concept that is especially applicable to working in online contexts. The transaction between the teacher and the student is seen to be dependent on two variables, in particular dialogue and structure (Moore, 1980). Dialogue is seen as important for bridging transactional distance (Moore, 1991; 2007), while the structure of a course frames the ways in which students are able to make their own interpretations of the what, how, and why questions with regard to tasks they are asked to accomplish. If the structure is loose, the students have greater opportunities for making their own interpretations. However, assessment of students’ work is necessary and despite the dichotomy between summative and formative assessment it should always involve both summative and formative assessment (Taras, 2005; 2007a; 2007b). Through the application of these theories, the aspects of teaching and assessment are brought to the fore.

The major challenge in the learning process is bridging the gap between different learning experiences (Illeris, 2009). Building on Piaget’s cognitive theory, Illeris (2009) classifies levels of learning from the perspectives of assimilative or accommodative learning. These concepts are not separated in practice, but emphasis is often placed on the assimilative learning perspective. Illeris (2009) explains the assimilative learning perspective as learning by addition, or, in other words, the learner adds new pieces of knowledge to what already exists. The accommodative approach or transcendent learning modifies existing schemes by a process of deconstruction and reconstruction. Space is found within the latter process to include previous experiences and knowledge acquired from other contexts, assignments, or experiences. In practice, Illeris (2009) suggests problem-based learning as one way of transferring knowledge between two different contexts. Thus, these concepts demonstrate ways of understanding the learning process, which are of significance for process-based assessment.

Bernstein’s (2000) theoretical framework in relation to pedagogical practice and the concepts of classification and framing provide the basis for an understanding of different power relationships between agents in the classroom. The theory of classification and framing was applied in order to understand what underpins the student-teacher relationship as well as the messages arising from introducing process-based assessment into practice. The concept of classification provides a framework for exploring relationships between different categories and between agents, discourse, and practices. Classification is constituted from the degree of insulation between the categories. The degree of insulation helps to recognise a unique identity, approach, or voice. Thus, it is possible to differentiate between strong and weak classification based on the extent of insulation between categories. The concept of classification is between categories, while that of framing is within categories.

Framing refers to what is inside a category and is carrying its message. Framing is the locus of control and varies according to the pedagogical relationship between the teacher and the student. This locus of control relates to a number of questions about students’ learning, such as who decides the frequency of reflections, which learning outcomes to focus on, how assessment is accomplished, and what to do with feedback. These questions reflect Bernstein’s (2000) concepts of selection, pacing, timing, and organisation of students’ learning in the student-teacher relationship. Furthermore, if framing is strong, the students have explicit instructions about how to deal with these questions; if framing is weak the students must take greater responsibility for interpreting and taking different decisions in their learning.

The results of the study are presented in the following section. In the presentation of the data, an attempt was made to show the student-teacher relationship from the perspective of the teacher’s role, the learning process, and the assessment process; a table was created with this goal in mind. In order to illustrate the different perspectives, the students’ voices are made evident via frequently used quotations. The students’ perceptions of process-based assessment were ambiguous and comparable to other educational experiences, such as the nursing programme in general. They were positive towards reflecting and reinforcing prior learning but argued strongly for developing new pieces of knowledge through activities supported by course literature and assignments, rather then developing previous knowledge. By reading, re-reading, and listening to the interviews, my perception of this particular group of students was that it was a group that was interested, engaged, and ambitious about the subject knowledge, particularly as it pertained to their daily work as nurses. From the questionnaire it was found that the entire group of students had experienced learning according to the knowledge transfer metaphor of desk teaching as described by Säljö (2000). Desk teaching involves the students being strongly monitored by the teacher with little opportunity for making their own decisions. Most of the students had been taught through such a teaching approach in both compulsory school and upper secondary school. Furthermore, a majority of the students regarded norm-referenced marks as unfair, as exemplified by one student who remembered “my teacher could not give me a four [five was the highest mark] because all fours were already occupied.” The students mentioned feedback from the teacher in their previous experiences as something positive. An example of this was expressed in the following statement: “studying at the upper secondary school I was informed what was good and what I should think about for improving.” The interviewees all had a similar experience of work, school, and higher education, and none had prior experience of process-based assessment.

The data was analysed by reading and re-reading the interviews. A first analysis resulted in three categories, or themes, which were inductively derived at a descriptive level. The descriptive themes of process-based assessment were

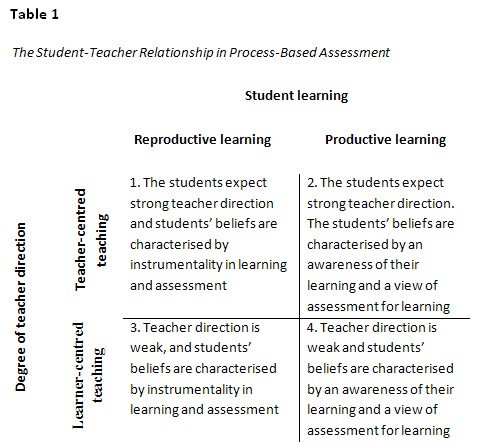

The analysis was brought to a deeper level by applying aspects of Illeris’s (2009) theory of assimilative and accommodative learning, which underpins the labels of reproductive and productive learning. The category of teacher directedness was derived by Moore (2007) as teacher-centred teaching or learner-centred teaching. The typology attempts to capture the relationship between the student and the teacher in process-based assessment. Each square in the quadrant in Table 1 is derived from the students’ reasoning in the interviews, from answers in the questionnaire, and from the contribution of the theoretical framework presented earlier. The quadrant indicates the complexity in the intersection between students’ beliefs about their learning process and the visible and tacit direction by the teacher. These intersections give rise to “fields of tension” (spänningsfält in Swedish) between the categories, which produce the content in the quadrant. All of the interviewees’ answers can be placed in the four categories, which constituted the following intersections: teacher-centred teaching and reproductive learning, teacher-centred teaching and productive learning, learning-centred teaching and reproductive learning, and learning-centred teaching and productive learning.

The typology shows the student-teacher relationship derived from the students’ narratives. The students’ experiences are complex because they have not taken a clear decision for any category. The names of the students are replaced by pseudonyms.

As reflected in the first quadrant, students argued for teacher-centred learning in which they conducted a reproductive strategy for learning. In this category, students expected teacher guidance to be authoritarian. The students waited for the teacher to give orders, which Elisabeth expressed as, “I wait for someone to tell me that now it is part two, write part two.” Cecilia strongly expressed that the written instructions should be given without room for interpretation. Her view was that the written instructions should provide information on “how you shall think and how you shall write and what to focus upon.”

In the students’ narratives of their learning, a web of reflections on their thinking and actions portrayed their subjective strategies. These strategies were often derived from a starting point of asking for references to use. As Linda commented, “Yes, but you always think that assignments shall be written with references and that everything shall be written with references. You are not really allowed to have your own opinion without having references.” Obviously, this student started to think of a strategy adopted from other assignments in the course and probably other educational experiences. For some students, their reasoning mirrored a simple equation of gaining knowledge, as Maggie enthusiastically expressed: “I had such limited previous knowledge. Through this it was really useful for me to see that I had learned a lot.” This student illustrated a knowledge dimension of fragments.

In line with the learning approach above, students’ reasoning of assessment was from a perspective of right or wrong, such as looking for an answer in the course literature. As Cecilia complained, “I didn’t have any feedback if I did right or wrong.” However, there are reasons to believe that the course had a pedagogy that supported this approach, which Linda highlighted: “it was just one assignment among others … we had a lot of small assignments to accomplish.”

As reflected in the second quadrant, the role of the teacher was visible in the instructions, where the teacher identified which learning outcome the students should reflect on. This delimiting purpose was not positive because it could decrease the students’ engagement, as Klara reflected: “I am not interested in working with children … I think that was why I didn’t feel the interest to write.” However, Sara expressed an extended role in her writing: “When I reflect, I think I am the one who decides what I shall write and how I perceive the questions.”

In the students’ learning, the pedagogy of process-based assessment started to come to the fore. As Linda observed, “however, you thought it was some kind of work, but it was about my knowledge.” Doubts were expressed from the perspective of sifting and using references. Jennie was confused: “I thought: ‘what shall I write?’ I know roughly what I have as previous knowledge, but if I shall write everything I know about children with autism then it will be a novel.” All students expressed these kinds of difficulties in the first meeting where process-based assessment was in use. Jennie was aware of her previous and rich knowledge of a particular subject but expressed difficulties in delimiting and choosing the more important parts in relation to the learning outcomes for her story.

The students also understood the assessment differently. At the start of her writing, when she was not building her story on literature, Jennie thought, “Will the teachers think I’m stupid now when I have less knowledge in the learning outcomes?” Klara continued and argued with confidence that a student story can be developed differently and without one right answer: “Connected to these three learning outcomes there were instructions to reflect upon each assignment, but that can be done with different approaches.”

As reflected in the third quadrant, the students had space for interpreting the instructions, but conflicts arose from expectations based on other educational experiences. In fact, the teachers were not as visible in the instruction to the extent that the students desired.

The students were frequently comparing the new learning experience with other educational experiences. Jennie reflected that “I learned much more in the other parts when we had lectures and seminars, and assignments to work with.” For the process-based assessment task, this student noted an engagement for learning as “find[ing] as much as possible in these three learning outcomes.” This created a feeling in several of the students’ stories of learning, which were constituted of compilations of literature. One aspect that influenced students’ actions and thinking was probably the course design, which Linda expressed dispassionately: “We had a dreadful amount of assignments, and this was one of many to accomplish.” In moments of pressure the students adopted a strategy of accomplishing, promptly forgetting the experience, and continuing with the next task. Three students felt that they were “taking a chance” by sending the document to the teacher.

From the assessment perspective, in the reproductive approach to learning the students asked for judgments expressed as right or wrong. Again, the feedback from the teachers confirmed and summarised the students’ efforts, but instead of asking for qualitative supervision Elisabeth argued that “the teacher must check that I am on the right track.” A few students received constructive feedback, but the feedback had no requirement for them to make changes to their work. Klara took this decision: “I got a comment from the teacher on how I could write and develop the text, but I didn’t do it.”

As reflected in the fourth quadrant, the students searched for the reflective moment that gave them support for further reflection. The role of the teacher highlighted an openness that supported students’ interpretations and decision-making regarding the task.

As they approached the end of the course, the students began to take extended decisions in relation to the instructions. Klara asserted that “the text should be connected to the course literature and lectures but I didn’t think those had so much to give. Instead, the text was developed more from our practice.” Klara continued and reflected on the knowledge she gained from the process-based assessment in relation to the assignments in the course. She commented that “in other assignments, I gained new knowledge … but the process documentation is only a reflection.” The student thought that there was something wrong when she had not developed (according to her understanding) new knowledge. Two students understood their knowledge as deeper. Klara observed how her previous knowledge had become more profound: “It (the text) felt as the text I wrote in my previous knowledge … but here (in practice) I saw it was possible to accomplish and in which form, so it had become deeper.” Linda continued and reflected, “My perspectives had become wider, because it was very much influenced by media before.” This moment of reflection and repetition was a positive activity for all students, as Cecilia noted: “There is nothing wrong with reflecting on your learning; it is positive.”

When the purpose of assessment was for learning, the students received questions and reflections from the teacher to elaborate and reflect on. Only one student received feedback, which was used for elaborating the knowledge during a two-week training period as a school nurse. Jennie expressed satisfaction with this: “I thought about these comments when I was at the school practice.” However, the students were aware of the need for formative assessment. Jessica articulated her critique on the feedback:

Yes, [it is important] that the teacher not just makes summaries or that the teacher in fact not at all make summaries. Instead I want comments and perspectives on what I have written from the teachers’ point of view. I do not want that feeling that I got something back which I wrote by myself, I ask for feedback from the teacher on what I have written.

Obviously, there was a gap between the students’ and teachers’ expectations of each other.

This study aimed at gaining a better understanding of the student-teacher relationship in process-based assessment. The typology of the four categories of thinking and action that was developed illustrates the diverse aspects of the teacher’s role in relation to the student’s approach to the learning process and also the diverse aspects of the student’s role in relation to teacher direction. The nature of the diversity relates to the fact that while students can be categorised strongly within one quadrant, there is considerable overlap. Furthermore, the ambiguity in the students’ narratives made it necessary to conduct a very close analysis in order to derive the students’ voices with regard to these four categories. The results did not clearly illustrate the extremes of teacher-centred teaching and reproductive learning and learner-centred teaching and productive learning from the starting point to the end of the process. Therefore, the students did not move from reproductive to productive learning in their learning process. Because of the diversity, the students’ previous experiences played an important role in understanding process-based assessment. The data revealed two categories, with particular approaches arising from previous experiences of teaching, learning, and assessment in relation to this new experience.

In conducting this analysis, the theoretical perspective of Bernstein (2000) was used in order to interpret and discuss the results based on the concepts of strong and weak classification and framing. In the first category – a traditional approach to teaching and learning – the students argued for a mode of teaching and learning that they were familiar with. From the students’ previous experiences, they knew very well how teaching and learning should be arranged, and they had clear ideas about what they wanted the teacher to do. This approach communicated a strong classification and framing in which the teachers and the students had clearly defined roles. These roles illuminate a power relationship in which the teacher monitors the students. The second category arises from a weakness in and a challenge to the traditional approach. This challenge most probably grew from entering into an approach of distance learning of this nature, in particular the reflective approach of process-based assessment. A starting point for this challenge is the students’ previous experiences of gaining feedback, insights they gained from previous educational experiences such as upper secondary school. These insights became evident when the students started to enter a productive thinking phase on learning. However, this process became stronger once the students gained insight into the pedagogy of process-based assessment related to the feedback they received from the teacher. The weakening of the traditional approach resulted in a challenge to the students’ previous beliefs about and reference points to teaching, learning, and assessment. This process can be seen as the cause of a state of confusion that was experienced by many of the students. The difficulty in moving on from this state of confusion was greater for some students than for others. In the second category, with an approach of process-based assessment, the students understood the learner-centred teaching. The locus of control changed accordingly because the students became more confident in their actions and thinking in relation to process-based assessment and probably distance learning as such. In the second approach, which involved weak classification and framing, the students were more aware of their own learning processes and their associated desires and claims.

The teachers’ goal was to implement and develop process-based assessment in this distance education course. The role was understood from a perspective of what the teachers actually did or did not do in relation to the two categories. The students’ approach to learning is a reflection of strong classification associated with teacher-centred teaching. The course design built on several assignments, which communicated a teacher-centred locus of control. Such design could be the root of the students’ strategy towards learning, which was to “accomplish and forget.” It is plausible to believe that the design of the template limited the findings. There is a high degree of structure with a teacher-centred approach in which the teachers control sequencing, organisation, timing, and pace (Bernstein, 2000) in students’ learning. These teachers did their best given the preconditions and their own interest in bringing about change. The process of change would probably have been smoother if the teachers had been familiar with support and training in the pedagogy of process-based assessment and if they had developed the template themselves. With a learner-centred approach, process-based assessment provided opportunities for dialogue and interpretation (Moore, 2007), but the teachers’ practices remained teacher-centred. Similarly, as the students entered their state of confusion, it seemed that the teachers themselves were trapped in the same space. This dilemma was illuminated in the process of assessment when the teachers provided feedback that did not challenge the students. It seems that the students moved more quickly towards a learner-centred approach to learning than the teachers moved towards a learner-centred approach to teaching.

The students were moving between strong and weak classification and framing in their learning. The strong classification in the students’ learning was expressed through a comfort with the structured approach to learning, one in which they knew how to act and perform. This structured learning environment is something the students had grown up with and were familiar with. When classification became weaker, the students’ educational awareness of the value in gaining feedback was heightened. This can be understood as contributing to a gap in terms of the development of a shared understanding in the student-teacher relationship. The pedagogy of process-based assessment involves weak classification and framing, arising from the nature of the learner-centred approach. Accordingly, the shift in the locus of control to the students gave them a stronger voice and more room for taking different decisions. However, the students acted in a counterproductive way in response to this opportunity; this was clear when they became satisfied with simply submitting and appeared uninterested in dialogue with the teacher. This counterproductive approach illuminates the power relationship between strong and weak classification, which also reflects the influence of the course design. Langer (2002) found that students have difficulties understanding this pedagogy. Unsurprisingly, capturing the learning process was a complex task for the students in this study. These difficulties could be seen to be the result of the strong classification being an obstacle at the start due to the students’ limited skills and prior experience with such an approach. The difficulty experienced in choosing content at the starting point of the process indicates their familiarity with a more reproductive strategy towards learning. When students are acclimatised to a traditional approach to teaching and learning, adjusting to the new approach is a big leap, especially when this is done without sufficient training. However, the productive approach to learning was visible in the students’ reasoning and insights into their knowledge. The three learning outcomes were a channel for tacit communication and strong classification and framing in the student-teacher relationship (Moore, 2007).

In order to change this locus of control through weaker framing, it is probably necessary to strive towards shared responsibility by increasing the level of freedom and control the students have over the learning outcomes. Accordingly, individual productivity and creativity could be stimulated to a greater extent by offering students more and open choices to address their professional needs, thus enriching the distance learning experience. Students who were not asking for the possibility of choosing their learning outcomes probably had stronger arguments in favour of the teacher-centred approach. It can not be overlooked that the use of a pre-set template affected the results. This template provided a tacit voice of structure from the teachers (Moore, 2007), which had several “check points” by focusing on the individual development of each student. Some degree of structure is clearly needed, but the key question is how much.

Taras (2005, 2007a, 2007b) argues for assessment as one process through which the students receive a judgement. If the judgement comes from the teacher, it is a voice of strong classification. The students were asking for a summative assessment in its most simplified form (i.e., being right or wrong). This thinking was a strong belief that was reflected in the students’ reasoning. When classification became weaker, the students gained insight into the fact that the answers could be diverse and did not necessarily follow a norm, particulalry in a group with such diverse backgrounds. The students also had an awareness of what they wanted from assessment to support their learning. But when the students received constructive feedback, they did very little in response. This gap between awareness and action could be interpreted as arising from an unequal power relationship, associated with the traditional approach to teaching and learning and based on strong classification and framing. Thus, the students were satisfied if they could interpret or justify that their achievements were perceived as having been accomplished from the teacher’s perspective. As a consequence, the process aspect in process-based assessment was moved to the background.

In summary, the key findings from this study lead to an increased understanding of the student-teacher relationship in the distance education context and, in particular, the ways in which the power relationship involves the teacher’s role, the learning process, and the assessment process. A pedagogical issue for students in distance education was highlighted: professional experience meeting a new paradigm for learning. In terms of the teacher’s role, the power relationship shows more openness than authoritarianism but also reveals greater demands on the student to take responsibility for his or her own learning. In terms of the student’s learning process, the power relationship illuminates a shift in reasoning, decision-making, and actions with regard to the new experience of openness in process-based assessment in distance learning, in contrast to a traditional approach to learning. The assessment process plays an important role in the student-teacher relationship, which also influences the learning process and, in particular, has implications for the role that students expect their teachers to play. The next stage of the study will explore the impact of the teachers’ beliefs about process-based assessment on this nursing education course.

Bergström, P., & Granberg, C. (2007). Process diaries: Formative and summative assessment in on-line courses. In N. Buzzetto-More (Ed.), Advanced principles of effective online teaching: A handbook for educators developing e-learning. Santa Rosa, California: Information Science Press.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique (Rev. ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-148.

Boyatzis, R. (1998). Thematic analysis and code development: Transforming aualitative information. London and New Delhi: Sage.

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data. London and New Delhi: Sage.

Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-Learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. London and New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Garrison, D. R., & Baynton, M. (1987). Beyond independence in distance education: The concept of control. The American Journal of Distance Education, 1(3), 3-15.

Harris, M. (2007). Scaffolding reflective journal writing - Negotiating power, play and position. Nurse Education Today, 28, 314-356.

Illeris, K. (2009). Transfer of learning in the learning society: How can the barriers between different learning spaces be surmounted, and how can the gap between learning inside and outside schools be bridged? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25(2), 137-148.

Langer, A. M. (2002). Reflecting on practice: Using learning journals in higher education and continuing education. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(3), 337-351.

Moore, M. G. (1980). Independent study. In R. Boyd & J. Apps (Eds.), Redefining the discipline of adult education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Moore, M. G. (1991). Editorial: Distance education theory. The American Journal of Distance Education, 5(3), 1-6.

Moore, M. G. (2007). The theory of transactional distance. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (2nd ed. pp. 89-105). New Jersey and London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

SAOL (2009). Svenska Akademins ordlista 13:e upplagan [The Swedish language 13th edition, in Swedish]. Stockholm.

Säljö, R. (2000). Lärande i praktiken. Ett sociokulturellt perspektiv [Learning in practice. A sociocultural perspective, in Swedish]. Stockholm: Prisma.

Taras, M. (2005). Assessment – summative and formative – some theoretical reflections. British Journal of Educational Studies, 55(4), 466-478.

Taras, M. (2007a). Assessment for learning: understanding theory to improve practice. Journal for Further and Higher Education, 31(4), 363-371.

Taras, M. (2007b). Machinations of assessment: Metaphors, myths and realities. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 15(1), 55-69.

Thorpe, K. (2004). Reflective learning journals: From concept to practice. Reflective Practice, 5(3), 327-343.

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council on key competences for lifelong learning. Retrieved from http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/sv/oj/2006/l_394/l_39420061230sv00100018.pdf

Swedish Research Council (2001). Ethical principles of research in humanistic and social science. Retrieved from http://www.vr.se

Wolcott, H. F. (2001). Writing up qualitative research (2nd ed.). London and New Delhi: Sage.