Puvaneswary Murugaiah

The Science University of Malaysia

Siew Ming Thang

The National University of Malaysia

Technology has brought tremendous advancements in online education, spurring transformations in online pedagogical practices. Online learning in the past was passive, using the traditional teacher-centred approach. However, with the tools available today, it can be active, collaborative, and meaningful. A well-developed task can impel learners to observe, to reflect, to strategize, and to plan their own learning. This paper describes an English as a Second Language (ESL) instructor’s attempt to foster interactive and reflective learning among distance learners at a public university in Malaysia, working within the framework proposed by Salmon (2004). The authors found that proper planning and close monitoring of a writing activity that incorporates interactive and reflective learning helped to raise the students’ awareness of their own learning process and consequently helped them to be more responsible for their learning. The students acquired significant cognitive benefits and also valuable practical learning skills through the online discussions. However, there were challenges in carrying out the writing task to promote this form of learning, including students’ professional and family commitments and cultural attitudes as well as communication barriers in the online environment. To address these challenges, the authors recommend the following: ensure tutor guidance, enforce compulsory participation, address technical problems quickly, commence strategic training prior to the beginning of a task, and implement team teaching with each instructor taking on certain roles.

Keywords: Reflective learning; online learning; distance education; English Proficiency course

Developments in educational technology have played a pivotal role in changing the dynamics of online education, namely distance education. Computer-mediated communication tools, both synchronous and asynchronous, allow learners to participate in interactive activities with their peers in a virtual environment. These tools are becoming so interactive and collaborative that they provide opportunities for instructors to achieve diverse pedagogic goals (Squires, 1999). For instance, Salmon (2002) successfully developed, moderated, and explored reflect-on-practice activities with an asynchronous text-conferencing system, while Lazarowitz and Natan (2002) combined computer-mediated communication (CMC) with cooperative learning to promote the power of a cooperative learning environment. The role of collaborative and interactive tools is crucial in online distance learning (ODL) as distant learners are separated geographically and even temporally from their peers and instructors and therefore are required to learn independently. This poses a major problem for them as they have to be disciplined and motivated to learn on their own. When students are unfamiliar with university education and distance learning, social interaction is as important as cognitive content for learning achievement (Kear, 2001). Social and emotional interactions are important as encouragement and acknowledgement are essential for motivation and learning (Rovai, 2001; Rourke et al., 2001).

Engaging in peer interaction activities involves student-instructor interaction, peer-to-peer collaboration, and active learning (Chen, Gonyea, & Kuh, 2008). These activities can assist students, namely ODL students, to collaborate and develop important skills in critical thinking, self-reflection, and co-construction of knowledge. Such learning environments can contribute to better learning outcomes, including development of higher-order thinking skills. A well-structured online unit offers essential support and development for learners to build their expertise in learning online (Salmon, 2002). Furthermore, with the advent of interactive tools, online learning can be more learner-centered if planned well and utilized fully. In a learner-centered online activity, students are expected to be responsible for constructing their own knowledge while engaging in the learning process. This includes reflecting upon their actions and thoughts and monitoring their own learning processes and knowledge construction (Garrison, 2009; Jonassen, 1999). Such activities happen on an individual basis but also through peer interaction. The instructor has a major role to play in assuring the success of this form of learning. She has to design activities that not only engage the students productively but are able to motivate and move them towards self-directedness. This paper explores to what extent an online writing task can achieve the above goals; as well, it explores the challenges faced by the instructor in the developmental process.

The School of Distance Education (SDE), Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) caters to adults from around the country. Their ages range from 23 to 72 years. A majority of these adults have scant knowledge about the mechanics of distance learning, namely the learning and delivery methods. The course delivery modes at SDE include printed materials, videoconferencing, electronic portal, and streaming Internet video. Learning via the Web is a novel feature for many, including those who are computer savvy.

A large number of distance-learning students at SDE, sometimes as many as 1,000, register for the basic English Language Proficiency course (as indicated in the SDE student records). This is due to the fact that English proficiency courses are compulsory for all students and low-proficiency students have to start with the basic course; whereas, students of higher proficiency begin with a higher-level course. The low-proficiency students view their attempts to improve language skills as an uphill task, and this problem is aggravated because they are learning on their own through a distance-learning system. Each proficiency level is handled by only one English language instructor. Hence, it is not surprising that the task of giving advice and guidance to these students is monumental. The instructor not only has to provide ample opportunities for them to practice the various language skills, but also needs to motivate them and help them to be more self-directed. The main author and researcher of this paper has been an English language instructor at SDE for 7 years. [From this point onwards, the main researcher will be referred to as the instructor.] Over the years, she has tried various ways to support her students effectively. These included using the Web to present activities, downloading exercises and language quizzes, using getting-to-know activities, presenting writing tasks, and providing feedback. However, she soon realized that her efforts were futile as improvement in her students’ language proficiency was minimal. They remained teacher-dependent, expecting her to spoon-feed them. Her involvement in the e-educator project led her to realize that a probable reason for this was that social and practical content was not prominent in the methods she employed. Her focus was primarily on cognitive content, that is, acquisition of basic language skills, which was insufficient to achieve her desired goals. As Kear (2001) points out, interactions with social and practical content are important for distance learners, who are coping with both university and distance education. In another study, Birch and Volkov (2007) found that ESL students who are shy to speak in English are willing to participate in online discussions. Thus, it is evident that for online learning to benefit ESL students, it must incorporate social interaction, collaboration, and reflection.

The e-educator module was a research project funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) and managed by the School of Education, University of Nottingham. The piloting of the e-educator module involved providing support for one year to a group of six online USM tutors (including the main researcher) who were teaching online distance learning courses in various disciplines. These tutors received online training modules that promoted interactive and reflective practices and were required to reflect on the pedagogical and affective issues presented in various units of the training modules. They also interacted with each other and their mentors in online discussion forums, blogs, and e-mails. Regular face-to-face meetings to troubleshoot and discuss problems reinforced this training. For more information on the e-educator module and the pilot project, please refer to Joyes, Hall, and Thang (2008), Thang and Joyes (2009), and Thang and Murugaiah (2009). The project website is available at www.echinauk.org.

Involvement in the e-educator project caused the instructor to realize the need to focus on the process of helping her students become more independent and reflective learners. In other words, her focus should be on how something is learnt, rather than on what is learnt (Clouder, 2000). Siemens (2005) concurs. According to him, learning in the digital age occurs through the process of interaction with various sources of knowledge and participation in group tasks. Reflection plays a significant role in this process. Brindley, Walti, and Blaschke (2009) share the same view. They affirm that knowledge construction occurs through interactions involving peer sharing. For higher levels of learning, reflection is key (Kanuka, Collet, & Caswell, 2002). Thus, it appears that interactive and reflective practices (the process of learning) contribute to knowledge construction (the product of learning). However, the instructor was rather apprehensive of the impact of such a practice on her students. Could her students adapt to the idea of learning online without face-to-face interaction? Lin (2008) points out that in adult learners, a gap exists between their old thinking and the new knowledge they encounter. In making adjustments to reduce this gap, they may feel disconnected at some points in their learning, which can lead to disruptions in peer collaboration (Brindley et al., 2009). Furthermore, the instructor was concerned whether her students would really learn with and from their peers through online interaction. Kim, Liu, and Bonk (2005) warn that communication difficulties, like slow feedback and unfamiliarity with group members, can hinder online peer-group learning. The issue of cultural influences on learning also needs to be considered. The objective of this study was therefore to seek answers to these questions in relation to teaching English writing skills to basic-level students, using an interactive and reflective approach.

Social constructivist theory underpins this study; it postulates that knowledge is constructed in a social environment when individuals reflect on their own and other people’s ideas (Maor, 2003). In other words, an individual’s understanding or knowing does not develop in isolation but through interactions with other people. Collaboration in a social learning environment is a vital element in any learning experience (Adams, 2006). An online learning environment is no exception. Online courses based on constructivist principles must be relevant, interactive, project-based, and collaborative, giving learners a certain degree of control over their learning (Partlow & Gibbs, 2003). The instructor becomes a facilitator, helping students to construct their own knowledge. Technology-enhanced teaching, from a constructivist viewpoint, should therefore bring about more student-oriented teaching, group work, and learning.

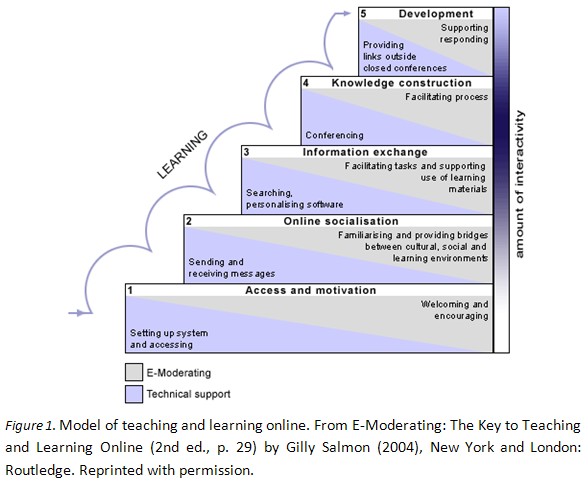

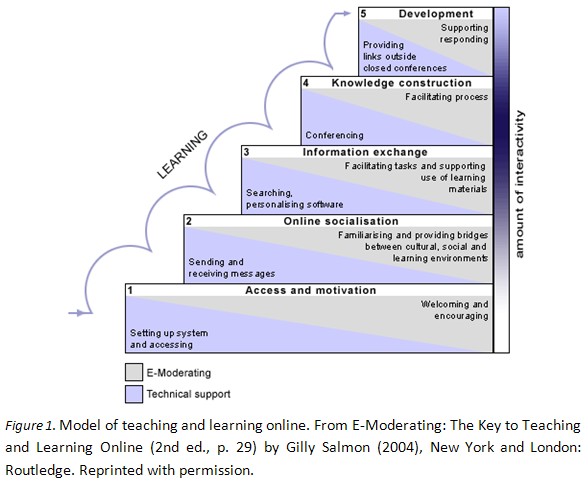

Salmon’s (2004) scaffolding model, teaching and learning through online networking, adopts constructivist theory. This model promotes online networking and group work while allowing the scaffolding of individual development. The two building blocks in the model are essential in promoting student interaction and learning:

This model was particularly useful for the online task designed by the instructor as it stresses the personal character of learning. It emphasizes that the learner is central in an online activity and that online learning is a social process. The model also demonstrates that both interaction and reflection are key in online learning. Thus, it is important to engage students in learning from one another through online interaction and reflection.

Salmon (2004) distinguishes five stages of online learning that an instructor should bear in mind when structuring and organizing an online activity (shown in Figure 1).

Stage 1 – access and motivation: As new online learners may experience apprehension and frustration in accessing an online interactive site, it is the role of the e-moderator to motivate and encourage them to learn online while ensuring that access to the online network is easily available.

Stage 2 – socialization: It is vital for an e-moderator to create an environment for online learners to share and exchange ideas by facilitating online work and cooperation.

Stage 3 – information exchange: At this stage, online learners interact with course content and other people involved in the online network (including the e-moderator). The e-moderator assigns tasks and requires learners to explore all relevant information available to them.

Stage 4 – knowledge construction: At this stage, learners hold online discussions regarding a task(s). These interactions can promote knowledge construction. In maintaining the online group, the e-moderator interacts with the learners and encourages them to contribute to the discussion.

Stage 5 – development: Online learners at this stage must become critical and self-reflective, as well as responsible for their own learning. They must be able to build on ideas acquired through online activities and apply them to their individual contexts.

The purpose of the study is to determine the extent to which an online writing task can result in interactive and reflective learning among distant learners at SDE. To accomplish this, action research is employed. Action research, which is a form of self-reflective inquiry to improve one’s own practice (Carr & Kemmis, 1986), involves solving problems and making changes or improvements. The basic principles underlying action research are to identify an issue or problem, to find a possible solution, to try it out, to evaluate it, and eventually to change the practice. Two processes are significant in action research: the actions that lead to learning and the learning that results from reflecting on one’s own actions. Self-reflection is crucial in examining one’s own work. It involves applying knowledge acquired from one’s experiences to improve practice (Ferraro, 2000). Action research, therefore, is learning in and through action and reflection (McNiff & Whitehead, 2002).

This study uses Salmon’s (2004) model of teaching and learning through online networking. To implement the 5-stage model, the instructor designed a guided writing task for her English Proficiency Level 1 students who had obtained Band 1 or 2 in the Malaysian University English Test. They were between 23 and 70 years of age, mainly from rural areas, and with varied professional backgrounds. As the task involved online collaboration and reflection, they used the e-learning portal provided by SDE as their learning platform. The portal, which was easily accessible by both students and instructors, provided salient tools for interaction, such as Wiki and discussion forums. For the online writing task, the discussion forum was used. The postings in the discussion forum regarding the task were analyzed qualitatively to examine the extent to which the task fostered interactive and reflective practice among students. The next section describes the online networking, reflection, and learning that occurred as the task progressed, based on the stages postulated by Salmon.

In implementing Salmon’s model (2004), the instructor took several measures to ensure that each stage was carried out effectively. The progress of the online task through the various stages could be discerned by students’ interactions and reflections in their postings. In this paper, initials identify the postings by the instructor (Ms. P) and the students.

This is the induction stage for online learning. As learning online was a novelty for many of the students involved, it was important to try to prepare them emotionally and mentally for the task ahead. To do this, the instructor tried to create a friendly and relaxed environment by introducing herself in the following manner:

Ms. P: Hi everyone, I’m Ms. P.M., your English teacher. Call me, Ms. P for short. We will be communicating a lot through this discussion forum. I will post many activities and exercises here for you to participate and try. The forum has been created for you. So feel free to introduce yourself, get to know others, post any query you have, etc. Since we seldom meet face-to-face, this is another convenient and effective way to communicate. You can interact with your peers as well as with me. So let us make it fun!

Technical and operational issues can hinder a student’s enthusiasm in participating online. Problems with operating the portal and accessing the online system needed to be addressed effectively to prevent students from becoming disinterested in online activities. As a result, the instructor encouraged her students to contact her via e-mail or telephone regarding any technical problems they encountered. She also provided them with the technician’s contact details for direct consultation. Moreover, she endeavored to respond quickly and efficiently to their queries to create a close rapport with them. This was rewarded with comments such as those below:

Z: Thank you, Ms. P and Mr. N. [the technician]. I now can read all the postings. I am excited. Now I can make many friends.

R: Ms. P, I nearly gave up with the portal…luckily Mr. N. helped me with the problem. I am happy I can contact you and my friends.

B: Ms. P, thank you. I am not good with computers, so I thought I surely cannot use the portal. With your help, I can use it…not only for English but also other courses.

Motivation is an important factor for the success of a student. As distance learners with a generally low level of English proficiency, their self-esteem and motivation levels were also low. It was apparent that throughout the five stages, they had to be motivated to access the online system and also to spend enough time and effort on the task posted to make them active online.

Ms. P: To realize that you are weak is the first step towards improving yourself. As you can see, many of you are weak in English…so you’re not alone. Let us work together to try to improve our English, OK?

Ms. P: So, many of you are from rural areas. But that does not mean you cannot improve your English. You know, I’m from Perlis…and I grew up and attended school in a rural area too. I was not good in English when I was young, but I started reading English story books and slowly I improved. So you can improve too. It’s never too late!

Creating such an environment would motivate them to try to improve their English.

Creating an online environment that was conducive to interactions among students was vital. So prior to the task, it was important for the instructor to ascertain that learners were beginning to interact with their peers and to establish online identities. She used the discussion forum for this purpose, encouraging students to experiment with this mode of socializing. Some introduced themselves to the community and shared personal details, problems, and other information.

R: Hi! My name is R. I am from Jitra, Kedah. Are any of you from Jitra? I am scared whether can pass English or not…so if got students from here, we can do group work.

N: I am N from Pasir Mas, Kelantan. My English is also very weak. Never use it at home or work. Last time, when in school, just repeated what teacher said, that’s all. I don’t know how I can now improve my English…so old already!

A: My name is A from Masai, Johor. How to improve English together when all of us are weak? It is like we say in Malay, ‘five multiplied by two is the same as two multiplied by five.’ [all in the same boat]

The purpose of socialization was to foster closer bonds and create a sense of comradeship among the learners. The introduction task met with success. Even those who were very weak in the language posted their introductions. There was a sense of togetherness as they felt that, like the others, they were also weak in the language. They consoled one another and some boosted their self-confidence by providing encouragement for their peers to take action on their weakness.

B: Don’t think you are alone. We from Kelantan are weak in English. That’s a fact. What to do? But many from the West coast, their English is OK.

I: You’re not the only one, B. Many of us are weak too. I think it’s no point we just talk about poor English. Like Ms. P said, let’s try to do something about it. She said she’ll help us. So why not we try?

Z: For me, able to write a few sentences in English is good already…I think I’m improving. Why not we all think like that? One step at a time.

At this stage, students interacted not only with each other but also with the content. The instructor requested that students read the notes about writing expository essays in their module (each student was given the course module at the start of the academic year). She also gave an online summary of the notes to reinforce their understanding. During this stage, the instructor introduced the task. However, to make her students aware of the importance of reflections and collaboration, she modeled reflective thinking and her expectations in the discussion forum prior to giving them the task.

Ms. P: Many of you use the discussion forum to know your friends, read my notes, etc. Now I want you to go one step further. When you do this writing task, I want you to recall the steps you had taken to do it. For example, after you write a short paragraph, trace the steps you had taken when writing that paragraph. This is called reflecting where we become aware of our own learning process. Write down your reflections in the forum. For example, I write: ‘There are many causes of air pollution. One factor that contributes to it is the emission of toxic fumes by factories. The factories do not filter the wastes before disposing them. Due to this, toxic fumes that contain ammonia, sulphur and other chemicals are released into the atmosphere. The health of residents who live nearby the factories is affected.’ After writing the paragraph, I try to recall my writing process. For example: ‘Like in the notes, I must first have a main idea and then supporting ideas. Then, I must make sure the tense used is the present tense because the topic is factual.’ This is called reflection. Do you have a clear idea of what reflection is now? If you are not clear, don’t worry. Let me know, I will help you. OK, I will give you one week to ask me about reflection. After that, I will give you the first task.

The implementation of the task was planned carefully. The instructor developed the task to suit her students. She provided clear guidelines and instructions to ensure that the task would flow smoothly. She also explained the aims of the task, her expectations, and their roles.

Ms. P: This is what I want you to do. I will give you a topic and you are required to write a short paragraph on it. Next, reflect on how you wrote the topic and jot down your reflections. Others would also post their reflections. Then reflect on and respond to your friends’ reflections. Don’t worry about your peers’ reaction to your reflections. By sharing your reflections, you can learn from one another. You can share a strategy that you used with another student and vice-versa. Reflect each time you write and share your reflections with your peers. You will certainly be in control of your own learning. Good luck!

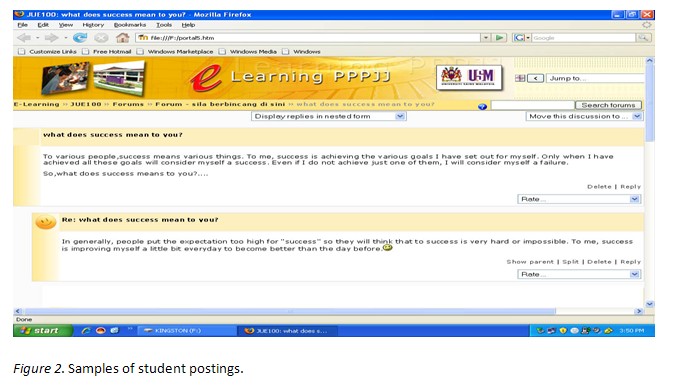

In the following week, she posted the topic, “what success means to you,” and requested a short paragraph on it (shown in Figure 2). Students were instructed to reflect on their writing process – how they wrote that paragraph, retracing their thought processes – and post these in the forum. After that, they had to read and respond to the reflections of others. Two weeks were allocated for this. Then another topic was posted and the students were required to repeat the same processes as before. Over a period of three months, five topics were given. The other topics within this writing task were “steps to improve the standard of English among distant learners,” “the role of the Internet in education,” “factors that contribute to an increase in crime rate in the country,” and “is money good or evil?”

It must be noted that this task was not a compulsory component of the course. Nevertheless, the instructor encouraged all to contribute to the task. During the three months the task was conducted, 27 students contributed fully to it, and their postings formed the data of this research. Others submitted the postings required but did not post their reflections. There were some who tried a few of the topics given to them, but their postings were not included in the data obtained for this study.

In this stage, the instructor monitored to what extent knowledge construction took place and endeavored to support students in their attempts to reflect on their own writing processes, share them with their peers, and comment on the reflections of their peers. This was a demanding task, but she adhered steadfastly to the following principles: (1) the instructor is accountable for maximizing student interaction (Hawkes, 2006); (2) the instructor must monitor and facilitate interactions as well as actively participate in the exchange of knowledge and reflections (Beldarrain, 2006); and (3) the extent to which students find value in their online learning experience and are satisfied with the results rests on the quality of those interactions (Dooley et. al, 2003).

In the initial stage, the instructor observed that some students’ personal reflections were rather limited.

A: I wrote what came to my mind.

N: I followed the paragraph writing guidelines that Teacher (Ms. P) gave.

T: I just remember how to develop a paragraph and use tenses.

Some displayed apprehension at having to reflect on their peers’ reflections.

M: My English is poor so I have nothing to comment.

K: I myself am weak in English…how to reflect on other reflections?

C: Sorry, how to comment when I don’t know whether my comment is right or not?

She then realized the need to support them further by giving guidance on how to reflect (both individually and in a group). Hence, she posted some questions that would prompt them on how to reflect.

Ms. P: What came to your mind? Go deeper and recall each step.

Ms. P: What are the guidelines that you followed? How did they help you in your writing?

Ms. P: Do you think your responses to your peers’ reflections would help them in their writing?

They were also encouraged to be constructive and not emotional in responding to their peers.

Ms. P: We are all here to learn. It does not matter whether your English proficiency level is lower than your peers’ or vice versa. Ali’s English is probably better than yours but your comment may help him to improve further in his writing. So think of how your response will benefit your peer. It does not matter how much your peer gains from your response. What is more important is the fact that you reflect on their personal reflections and present a constructive response that can assist him/her in his/her learning.

Due to the intervention and more practice sessions, students’ reflections and feedback improved noticeably.

B: I did an outline of the topic, and then I wrote. Then I checked for coherence, and correct vocabulary. I think this way is good. [student reflection]

K: First I wrote the main idea and then thought of how to develop it. I checked to see whether my points support the main idea. [student reflection]

R: Don’t write in Malay and then translate. Think in English. It is difficult at first, but you can improve your English this way. [student’s comment on a peer’s reflection]

F: Always check whether there is a main idea and supporting sentences. Sometimes our sentences don’t support the main idea, for example we give a wrong example for the main idea. [student’s comment on a peer’s reflection]

In this stage, learners are able to reflect on their own learning process to achieve the desired goals. An analysis of the students’ discussion revealed that as the activity progressed students were applying some of the suggestions offered by their peers in their reflections.

A: I don’t do an outline before I write. But after R’s suggestion, I tried. I find it is easier to write.

T: Thank you, Z…you are right. I now think of main idea and supporting ideas as the roof and pillars of a house…it’s easy to understand.

D: I also like football, so I thought why not, like M, I read the sports section in the Star [newspaper] to learn new words. I read what I like and at the same time improve my vocabulary.

The online writing activity, featuring reflections and collaboration, attempted to assist students in self-directed learning and in improving their English-language writing skills. As this was a student-centered activity, the instructor took on the role of a facilitator. However, she soon found herself providing pedagogical knowledge, managing the learning context, acting as counselor and advisor, and handling technical problems. This experience is in tandem with Maor’s (2003) claim that online instructors play four roles: pedagogical, social, managerial, and technical.

During the online task, the instructor found the pedagogical role most demanding. She was aware that her students had limited knowledge and skills as far as reflections were concerned. Even their collaborative skills were lacking. Hence, she had to figure out ways to address these problems. Despite some improvements, in the end she had to admit that her students’ contributions lacked depth. Thus, it would appear that a sound knowledge of learning strategies is vital. Strategy training may have to be given before attempting to instill reflective thinking skills.

The instructor also found that the managerial role was not easy. It involved planning the task from beginning to end. She had to ensure that the task was appropriate for the students’ level of proficiency, learning environment, and social background. The versatility and capacity of the learning platform also had to be taken into consideration. Monitoring and evaluating the task proved to be even more challenging. She also had to closely monitor and evaluate the students’ contributions and interactions so that they did not deviate from the aims of the task. Aside from these concerns, students’ interest and pace in performing the task had to be monitored and maintained. This included intervening at appropriate times to encourage them to continue and to be more reflective in their contributions.

Maintaining positive affective conditions was also a vital role of the instructor. Thus, the instructor had to don the social hat and find ways to boost learners' self-esteem, to motivate them, and to provide a supportive learning environment.

Last but not least, technical problems had to be attended to. Fortunately, the instructor could forward major problems to the technical staff support person. Her role was mainly limited to solving navigational problems faced by those who were unfamiliar with the e-learning portal.

From the findings, it would appear that interactive and reflective practice can be carried out online. Over three months, the online task fostered this practice to a certain extent. Students’ initial apprehension of the task and their role was slowly replaced by improved participation and contribution to the discussion. A congenial and relaxing atmosphere put students at ease with their peers and instructor.

K: I was shy at first because my English is poor. But when I read the reflections made by my friends, I realized that all of us are weak in English. So we can learn together. I relaxed. I enjoyed reading my friends’ comments. Some were so funny.

D: Ms. P, I got an idea…you become a student and we become the instructor…because we are now experts in reflection!

Students’ sharing also revealed that their drive to learn was enhanced, probably because learning from peers is less formidable than from teachers. There is comradeship among students; they can relate to one another in a relaxed manner (Wei & Chen, 2006). As a consequence, in the current study the students were more at ease with their friends, appeared more motivated, and also believed that they could assist their friends. This result was evident in the study.

W: Don’t worry…our gang here is ready to help you, S. Just say what you don’t know…main idea? Coherence?...we can teach you. Right, Ms. P?

The postings reveal that student interactions among peers and their reflections benefitted them, especially in learning English. They managed to learn, unlearn, and/or relearn new knowledge. As proposed by Tsai (2004), these students, through learning to learn, have learned not only to restructure their knowledge and to make meaningful links with other forms of knowledge and experiences, but also to monitor and review their own learning. Peer interactions can help them to have better control of their learning, which leads to self-directed learning.

S: I feel I am learning to write all over again. This time I am doing the learning with some help from others. I like that.

B: I think I learn better by discussing with my friends. Learning on my own is boring.

H: Learning to write like this is fun because it is learning in a group. You enjoy but at the same time you learn to write in English.

The findings also demonstrate the challenges faced by the instructor in carrying out the task. The instructor had to monitor the task and ensure that students’ interest was maintained. It is not easy for adult learners to accept and adapt to new technology and ways of thinking, as pointed out by Lin (2008) and Brindley et al. (2009). This problem was evident in the initial stages when some students expressed their reluctance to participate in the activity.

J: I’m not good with computer at all. My children help me to access the portal because I cannot. So I don’t want to take part.

K1: I don’t know anything about computer or portal or e-learning. Difficult for me.

Furthermore, due to their various professional and family commitments, some of the students viewed the task as time-consuming, and this affected their motivation to participate actively in the task. Thang et al. (2010) found that these factors were constantly used by Malaysian Smart School teachers to explain why they could not participate more actively in given online tasks. Ostlund (2008) attests to the negative impact of adult responsibilities on distance learning. As distance learners, they have to juggle study time with work and family.

Z: I take a long time to do this writing because I’m weak. I sometimes am fed up because I can only do after my work and my children are sleeping…I get tired.

Additionally, in a few instances interactions were affected by the reluctance of some students to comment on their peers’ reflections because they felt that doing so would be disrespectful.

L: I like to read other comments but I don’t like to comment. How to give comment when I am not good in English…like show off only!

M: So funny…as if I so good, I tell my friends what I think of their comment. Sorry la …I am commenting because must comment. May be my comment not good…

Thang et al. (2010) also found evidence of this cultural attitude in a project with Malaysian Smart School teachers who were reluctant to post too much because they were afraid that their comments would be disrespectful to their peers or that they would come across as “showing off.”

Another challenge faced is the communication barrier brought about by the absence of face-to-face communication. Rheingold (1993) points out that, “the authenticity of human relationships is always in question in cyberspace, because of the masking and distancing of the medium, in a way that it is not in question in real life.” (p. 129). Boyd (2007) and Kim et al. (2005) support this observation. The Malaysian context revealed a similar finding. Thang et al., in a study of online participation by a group of Malaysian Smart School teachers, found that the teachers were reluctant to participate online and attributed this to the fear of facing an unknown audience in the virtual world.

The present study has several implications for ODL practice and research in Malaysia. Overall, the online interactive and reflective writing activity seems to have managed to raise the students’ awareness of their own learning. Those who actively participated in the given task appeared to have learnt to reflect and managed to apply it in improving their writing skills in English. They also found that peer reflections and evaluation had motivated and helped them to write better. Thus, they had not only acquired significant cognitive benefits, but also valuable practical learning skills through the online discussions. Maor and Volet (2007) emphasize that online discussions can contribute to improved learning skills as well as to the quality of learning. The interactive and reflective approach has also promoted new knowledge construction and meaningful learning among online learners, a finding similar to that of Celentin (2007).

A tutor’s guidance is crucial for the success of interactive and reflective learning. His or her intervention can address student problems with technology, with team members, and with content. The findings reveal that the instructor’s guidance reduced such problems and that, to a certain extent, successful learning was achieved. It is evident that distance education students in the study benefitted from this form of learning.

However, the study also identified some challenges. Lack of participation due to professional and family commitments, cultural factors, and communication barriers cannot be easily resolved as they will need not only careful thought and planning but also changes in mindset and policies (including government and school policies). Nevertheless, it is possible to undertake certain measures to minimize the problems and to ensure greater success in future attempts. One way is to enforce compulsory participation as recommended by Birch and Volkov (2007). Technical problems also need to be addressed quickly to enable smooth online interactions among students. A comfortable and reliable technological environment facilitates group online interactions (Koh & Hill, 2009; Thang et al., 2010). Moreover, strategy training should be provided prior to the commencement of a task (Brodie, 2007), which helps to reduce student anxiety about the task as well as to ensure its smooth implementation. Factors such as age, group size, culture, and appropriate technological tools should be given due consideration when determining the task (Koh & Hill, 2009). Last but not least, team teaching should be implemented with each instructor taking on certain role(s). This form of learning is too demanding for one instructor (as shown in this study), especially if she or he is handling a large group of students.

Finally, the researchers would like to acknowledge that the preliminary nature and short duration of this study do not permit generalizations and would like to propose further research on a larger scale to establish to what extent these findings are applicable to a wider context.

This article is based on the e-educator project funded by the Higher Education Funding Council for England in the United Kingdom.

Adams, P. (2006). Exploring social constructivism: Theories and practicalities. Education, 34(3), 3–13.

Beldarrain, Y. (2006). Distance education trends: Integrating new technologies to foster student interaction and collaboration. Distance Education, 27(2), 139–153.

Birch, D., & Volkov, M. (2007). Assessment of online reflections: Engaging English second language (ESL) students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(3), 291–306.

Boyd, D. (2007, May 13). Social network sites: Public, private, or what? Knowledge Tree. Retrieved from http://kt. flexiblelearning.net.au/tkt2007/?page_id=28

Brindley, J., Walti, C., & Blaschke, L. (2009). Creating effective collaborative learning groups in an online environment. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(3), 1–18.

Brodie, L. (2007). Reflective writing by distance education students in an engineering problem based course. Australasian Association of Engineering Education, 13(92), 31–39.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical, education, knowledge and action research. Lewes: Falmer.

Celentin, P. (2007). Online education: Analysis of interaction and knowledge building patterns among foreign language teachers. Journal of Distance Education, 21(3), 39–58.

Chen, P., Gonyea, R., & Kuh, G. (2008). Learning at a distance: Engaged or not? Innovate, 4(3). Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=438&action=article

Clouder, L. (2000). Reflective practice: Realizing its potential. Physiotherapy, 86(10), 517–522.

Dooley, K. E., Kelsey, K. D., & Lindner, J. R. (2003). Doc@distance: Immersion in advanced study and inquiry. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 4(1), 43–50.

Ferraro, J. M. (2000). Reflective practice and professional development. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teaching and Teacher Education. Retrieved from http://www.ericfacility.net/ericdigests/ed449120.html

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Implications of online and blended learning for the conceptual development and practice of distance education. The Journal of Distance Education, 23(2), 93–104.

Hawkes, M. (2006). Linguistic discourse variables as indicators of reflective online interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 20(4), 231–244.

Jonassen, D. H. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional theories and models (Vol. 2). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Joyes, G., Hall, C., & Thang, S. M. (2008). The e-educator module: A new approach to the training of online tutors. International Journal of Pedagogies & Learning, 4(4), 130–147.

Kanuka, H., Collet, D., & Caswell, C. (2002). University instructor perceptions of the use of asynchronous text-based discussion in distance courses. The American Journal of Distance Education, 16(3), 151–167.

Kear, K. (2001). Following the thread in computer conferences. Computers & Education, 37(1), 81–99.

Kim, K.-J., Liu, S., & Bonk, C. J. (2005). Online MBA students' perceptions of online learning: Benefits, challenges and suggestions. Internet and Higher Education, 8(4), 335–344.

Koh, M.H., & Hill, J.R. (2009). Student perceptions of group work in an online course: Benefits and challenges. Journal of Distance Education, 23(2), 69–92.

Lazarowitz, R. H., & Natan, I. B. (2002). Writing development of Arab and Jewish students using cooperative learning (CL) and computer-mediated communication (CMC). Computers and Education, 39(1), 19–36.

Lin, L. (2008). An online learning model to facilitate learners’ rights to education. Journal for Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(1). Retrieved from http://www.distanceandaccesstoeducation.org/Results.aspx?searchMode=3&criteria=en

Maor, D. (2003). The teacher’s role in developing interaction and reflection in an online learning community. Educational Media International, 40(1), 127–138.

Maor, D., & Volet, S. (2007). Interactivity in professional online learning: A review of research based studies. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(2), 269–290.

McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2002). Action research: Principles and practice (2nd ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Ostlund, B. (2008). Prerequisites for interactive learning in distance education: Perspectives from Swedish students. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24(1), 42–56.

Partlow, K. M., & Gibbs, W. J. (2003). Indicators of constructivist principles in Internet-based courses. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 14(2), 68–97.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(1). Retrieved from http://cade.icaap.org/vol14.2/rourke_et_al.html.

Rovai, A. P. (2001). Classroom community at a distance: A comparative analysis of two ALN-based university programs. The Internet and Higher Education, 4, 105–118.

Salmon, G. (2004). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online (2nd ed.). London: Routledge Falmer.

Salmon, G. (2002).E-tivities: The key to active online learning. London: Routledge.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: Learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/index.htm

Squires, D. (1999). Peripatetic electronic teachers in higher education. ALT_EJ, 7(3), 52–63.

Thang, S.M., Hall, C., Murugaiah, P., & Azman, H. (2010). Creating and maintaining online communities of practice in Malaysian Smart Schools. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Thang, S. M., Murugaiah, P., Lee, K. W., Hazita A., Tan, L. Y., & Lee, Y. S. (2010). Grappling with technology: A case of supporting Malaysian smart school teachers' professional development. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 26(3), 400–416.

Thang, S.M., & Murugaiah, P. (2009). Investigating Malaysian tutors’ perceptions of the e-educator. Malaysian Journal of Distance Education, 11(1), 71–89.

Thang, S.M., & Joyes, G. (2009). Localisation of the e-educator module: The Malaysian experience. Turkish Journal of Distance Education (TOJDE), 10(2). Retrieved from http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/

Tsai, C. C. (2004). Beyond cognitive and metacognitive tools: The use of the Internet as an 'epistemological' tool for instruction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 525–536.

Universiti Sains Malaysia (2006). Student records of the school of distance education.

Wei, F. H., & Chen, G. D. (2006). Collaborative mentor support in a learning context using a ubiquitous discussion forum to facilitate knowledge sharing for lifelong learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(6), 917–935.