Julie Mackey

University of Canterbury, New Zealand

Terry Evans

Deakin University, Australia

The article explores the complementary connections between communities of practice and the ways in which individuals orchestrate their engagement with others to further their professional learning. It does so by reporting on part of a research project conducted in New Zealand on teachers’ online professional learning in a university graduate diploma program on ICT education. Evolving from social constructivist pedagogy for online professional development, the research describes how teachers create their own networks of practice as they blend online and offline interactions with fellow learners and workplace colleagues. Teachers’ perspectives of their professional learning activities challenge the way universities design formal online learning communities and highlight the potential for networked learning in the zones and intersections between professional practice and study.

The article extends the concepts of Lave and Wenger’s (1991) communities of practice social theory of learning by considering the role participants play in determining their engagement and connections in and across boundaries between online learning communities and professional practice. It provides insights into the applicability of connectivist concepts for developing online pedagogies to promote socially networked learning and for emphasising the role of the learner in defining their learning pathways.

Keywords: Connecting online and professional communities; online education; networks of practice; professional learning; communities of practice

Research focusing on the intersections between work and study, and particularly the role of online learning for professional development, represents an area of growing interest, not only in teacher education but also in other professional learning, development, and support (Conrad, 2008; Maor & Volet, 2007). The advent of online learning has been accompanied by burgeoning interest in the notion of community to support sociocultural approaches to learning. Garrison and Cleveland-Innes (2005, p. 135) suggest that “an interactive community of learners is generally considered the sine qua non of higher education.” Networked learning has been accompanied by a growing interest in approaches that employ communication technologies to foster collaborative processes, interaction (Cousin & Deepwell, 2005; Sorensen, 2005), and the social construction of knowledge (Edwards & Romeo, 2003). Consequently, attention has been given to understanding the potential and characteristics of online learning communities (Garrison, 2007; Goodfellow, 2005; Henri, Charlier, Daele, & Pudelko, 2003; Henri & Pudelko, 2003; Palloff & Pratt, 2007).

Higher education institutions adopting these social constructivist theories tend to be prescriptive in the way formal online courses are organised and set expectations for students to participate in online interactions as part of their course work. That is, social networking is mandated rather than organic and, as such, may encourage instrumentalist participation. Such approaches are supported by “a general and intuitive consensus in the literature . . . that the learner builds knowledge through discussions with peers, teachers and tutors” (Dysthe, 2002, p. 343), and others, for example, Geer (2005), Wilson, Ludwig-Hardman, Thornam, and Dunlap (2004), who advocate the role of community in supporting learning via interaction and collaboration. Slevin (2008, p. 116), considering the role of social interaction in e-learning contexts, challenges educators to ask, “How can institutions of learning best deploy modern communication technologies in order to engage and interact meaningfully with those seeking knowledge, guidance and inspiration?”

A problem with institutional perspectives of socially constructed learning is that the zone of interaction is usually confined to the online course community. There is little acknowledgement of the overlapping experiences of participants in communities of practice and other informal learning networks beyond the online course. Downes (2006) hints at this pedagogical weakness, suggesting that within formal online courses there is a tendency for community formation to be an adjunct of the course content, rather than the community itself driving learning interactions and determining salient content and resources. Discussions and interactions are shaped by content and curriculum, and the existence of a course community corresponds with the beginning and end of the course.

This insular view of community, bounded by course curriculum and timelines, is problematic for professional learning and highlights a tension between the underlying philosophical stance and the pedagogies adopted by universities. A central tenet of sociocultural epistemologies is that learning is vitally situated within the context of its development and that “understanding and experience are in constant interaction” (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 51). As Lave and Wenger (1991) describe in their theory of social practice, there is a “relational interdependency of agent and world, activity, meaning, cognition, learning, and knowing” (p. 1). Brown, Collins, and Duguid (1989) champion a similar position, stating that “activity, concept and culture are interdependent” (p. 34). According to Lave and Wenger (1991) learning is entrenched in social activities and occurs naturally in workplace interactions outside formal educational or training endeavours; learning is inextricably entwined with making meaning, sharing social and historical practices, forming identity, and belonging to community. How then do participants in formal, course-based learning make sense of and connect their simultaneous and overlapping experiences? Furthermore, how might participants’ experiences inform an understanding of learning as interconnections between practices, communities, members, and opportunities?

This article argues that there are strong links between social learning theory, formal online learning opportunities, and authentic learning in communities of practice. Furthermore, there is merit in positioning multimembership of communities of practice, enabled by e-learning and virtual learning environments, as examples of connectivist pedagogies in action. Wenger (2007, in Dyke, Conole, Ravenscroft, & de Freitas, 2007, p. 93) suggests that “social learning theory has profound design implications for the design of pedagogical e-learning” and that “rather than focusing solely on the design of self-contained learning environments, . . . e-learning also explores the learning potential of emerging technologies, that is, the ways in which these technologies amplify (or curtail) the learning opportunities inherent in the world” (p. 93).

Wenger’s (1998) social theory of learning underpins the research reported in this article. The ensuing discussion describes how elements of that framework, such as multimembership of communities, boundary crossing, and brokering can be interpreted as connectivist pedagogies and understood through the multipoint connections teachers develop through their online professional development. The perspectives of the teachers in this study provide insight into how universities might design learning environments that foster personal professional learning in and between networks of practice.

The research (conducted by Mackey for her Ph.D.) investigated the learning and professional experiences of 15 teachers studying a Graduate Diploma in ICT in Education at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, between 2005 and 2008. Case-study methods were used to conduct the research. The case was bounded in the sense that it centred on the teachers involved in the particular online professional development program. However, the boundaries between the teachers’ study and their work, and between local and virtual contexts, and the interrelationships with the broader social, political, and economic milieux also informed the case study.

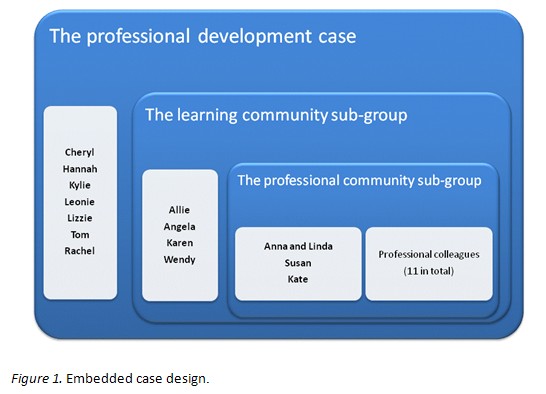

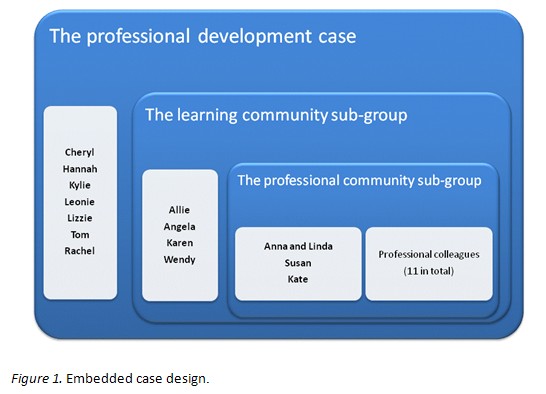

The study was designed, therefore, as a holistic case study with embedded cases (Yin, 2006); a conceptual diagram is provided in Figure 1. The holistic case is about the experiences of 15 teachers enrolled in a specific online professional development program. The embedded cases are sub-cases which contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of an issue or condition. The first level of embedded cases in this study comprises eight of the fifteen teachers and these subcases enable an in-depth analysis of the activities within the online learning environment. The second level of embedded cases, the professional community subgroup, comprises a nested group of four teachers within the learning community subgroup; these four teachers add depth to the study by including data from their school communities of practice. This nested design, with embedded case studies, enables a deeper level of analysis than is possible across the holistic case. All 15 teachers contributed to an overall understanding of how teachers learn, and where they situate their learning as they engage in online professional development. The purpose of the embedded cases was not to condense teachers’ experiences into a homogenous explanation of what it means to engage in online professional development, but rather to identify and illustrate the various experiences, issues, dilemmas, and impacts that contribute in some way to teachers’ professional learning in, and between, communities.

Thirty interviews were conducted with 15 teachers to provide in-depth perspectives about online study. In addition, all available online activity records drawn from 65 course enrolments across 11 separate courses were analysed for these teachers to provide a measure of their online engagement. These data sources were complemented with examples of online course participation (forum postings, peer review comments, shared documents, and activities) and assignments; and for the nested subset of teachers, interviews were conducted with 11 school peers to obtain an external perspective from close-at-hand colleagues who were not studying in the online courses. These strategies, along with an examination of official documents and the online course sites, contributed depth and detail to the case data.

From the outset this research drew on Wenger’s (1998) communities of practice as a theoretical framework in designing the study, shaping the methodology, and guiding the data collection, analysis, and interpretation. There was a tension in adopting and implementing this framework. While valuable as a descriptive theory for studying adult learning in natural settings (particularly applicable within the school context), the theory’s propositions raised questions around the existence of online communities. Wenger’s social learning theory was useful in interrogating the online learning community, but it also highlighted weaknesses, or what was not rather than what was, social practice. These questions prompted a closer analysis of the participants’ perspectives and the responsibility they took for designing their personal learning connections in and between communities. This extends understanding of where participants situate their learning, how they use interaction to meet their own learning needs, and how they manage their professional learning experiences.

The research focused on the perspectives of teachers who were motivated to learn about ICT, through ICT-mediated learning, but who had little or no experience of learning online themselves. They were experienced classroom teachers who were simultaneously encountering the unsettling experience of being learners and novices in a virtual learning environment. They were learning about the pedagogical use of ICT while learning with and through ICT, which added a further dimension to the overlapping environments of work (community of professional practice) and study (professional learning community).

The research also investigated the diffusion of teachers’ learning experiences beyond their own classrooms into their schools and professional communities. Some participants were responsible for leading and supporting ICT integration amongst their colleagues, thus creating potential for their professional learning to produce benefits beyond their own immediate practice.

All 15 participants held a teaching qualification and were enrolled in two and up to seven online courses during the data collection period (2005–2008); they represented a range of teaching experiences, ages, and predispositions towards online study. Participants were employed in early childhood (1), primary (8), intermediate (1), and secondary (5) education. The participants were also geographically spread, and although seven lived in Christchurch, none worked in the same school or appeared to know each other previously; another seven were located elsewhere in New Zealand; and one worked in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

A discussion of selected findings and their analyses follows. It draws on both quantitative and qualitative data, explores one participant’s engagement in detail, and uses related theory for the analytical discussion.

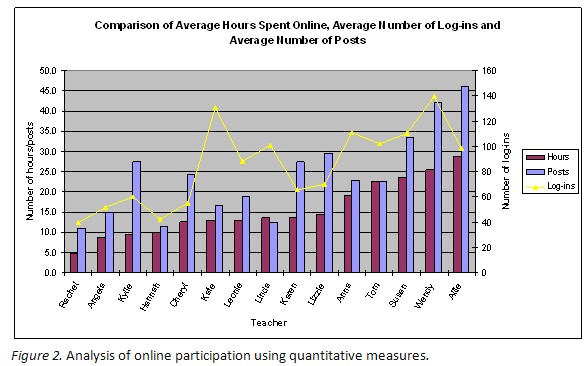

The quantitative measures of analysis identified wide variations in the levels of participation by teachers. Three quantitative measures were used to evaluate teachers’ online participation in each course, namely hours spent logged in to each course site, frequency of log-ins, and number of posts made to discussion forums or activities. The chart below illustrates the variation in participation reflected in the average measure for each teacher (based on the data analysed from each course in which they participated).

Quantitative data from learning management systems (LMSs) provide useful measures of what are rather superficial matters of learning; for example, log-in frequencies do not measure or reflect the learning processes or the quality of learning (Hansmann, 2006; Pena-Shaff & Nicholls, 2004). Interpretations of learning activities are achieved when quantitative records are complemented by contextual information about students’ learning and critical thinking within their learning contexts (Janetzko, 2008). This research not only triangulated the quantitative measures with such information but also drew substantially on teachers’ own reflections and comments about their online learning experiences.

The interpretation of teacher’s experiences was informed by Wenger’s (1998) communities of practice with particular attention to the processes of multimembership of communities. Teachers’ dual membership in professional and online communities can be conceptualised as boundary spanning which has the potential “to create continuities across boundaries” (Wenger, 1998, p. 105). These continuities or connections can be forged through documents, terms, and concepts, which connect practices from one context into another, and through the actions of “people who can introduce the elements of one practice into another” (p. 105). Not all experiences of multimembership entail brokering—something which Wenger describes as a complex activity requiring “processes of translation, coordination, and alignment between perspectives” (p. 109). The boundary of a community of practice can be envisaged as a delineation of practices and membership, but it can also be regarded as a permeable zone representing opportunities for overlap, connections, and participation by outsiders or newcomers. When community members traverse these intangible boundaries they are exposed to new learning opportunities that can be translated or introduced to the practices of their originating community. A discussion follows of the participants’ experiences of dual membership in relation to their connections with the online community and of their processes of translation, coordination, and alignment between their online and professional communities.

The analysis of teachers’ online participation (as shown in Figure 2), combined with content analysis of online posts and contributions, demonstrated high levels of activity and strong indicators of social presence in the online community by some teachers and much weaker indicators for others. However, what was evident from teachers’ interviews was that their perceptions of learning connections and interactions were considerably different from the picture gleaned from the LMS data or from the interpretations that might have been assumed by lecturers. What was most telling, however, was that even the most apparently active teachers in the online environment were pragmatic and purposeful about their involvement in the online community.

In order to illustrate how these characteristics and behaviours played out in the online environment, and how they were perceived by the participants, the following section will describe the experiences of one teacher, Allie, who was particularly active in all of her online courses.

Allie averaged the most time online per course and made the highest average number of posts across the three courses in which she was enrolled. An analysis of Allie’s online postings also indicated strong social presence, evidenced through her use of informal language (e.g., “ha,” “darn,” “yikes”), conversational style (e.g., “so true,” “I know, I know”), text symbols (e.g., exclamation marks, ellipsis marks), humour, and emoticons to convey a personal dimension within her posts. She disclosed aspects of her personal life, frequently responded to others, greeted people by first name, used rhetorical questions, referred to the content of their contributions, and wrote affirmatively. Allie was not alone in these behaviours, as almost all of the participants exhibited similar social presence in their online activities. Even the most reticent of the online community subgroup, Angela, slowly gained confidence and reported that she enjoyed facilitating a group activity and felt more at ease in the online environment.

When Allie joined a group activity she was proactive in initiating processes, encouraging others, and taking personal responsibility for contributing to the task. She was also sensitive to others and willing to accommodate different perspectives or approaches. Online posts also indicated that Allie confidently requested clarification or help and addressed questions to both the lecturer and other course members. She was not afraid to respond to feedback from the course lecturer when she felt her ideas might have been misinterpreted.

Allie, like the majority of the online subcommunity participants, conveyed a sense of mutual engagement with others in her online postings. She placed herself in the role of fellow teacher, assuming others to have similar experiences, and identifying with the common practices and experiences of teaching. Allie’s language also embraced others as members of the wider teaching community, assuming common ground and mutual interests (e.g., “most of us who have tried some sort of multimedia project in our room”; and “I really don’t think we have a choice as teachers”). Many of Allie’s online posts reflected on the prescribed readings for the course or peer presentations, linking theoretical ideas with her own experience. While the posts were practical rather than theoretical, they represented cognitive processes connecting new ideas or strategies with Allie’s beliefs and everyday practice. Again, Allie’s responses were typical of the online community subgroup, where inclusive salutations, reference to others’ work or comments, and reflections on teaching in relation to theoretical ideas were common in the online forums. Two interviews were conducted with Allie in her classroom after school hours, and one interview at a later date after she had moved to a library-based learning centre established to support the use of digital technologies in school and community-based programs. The interviews focused on Allie’s perceptions of her online learning, her connections with others online, and the connections she made between her online learning experiences, her teaching, and her school community of practice.

In contrast to her online persona and what appeared to be active engagement in the online environment, Allie’s saw herself as “very individual” and someone who did what was required with “not a lot of extra mixing.” However, she valued online interactions and commented that she “[replied] to comments—not because you need to—[but because] it’s interesting to read comments.” Allie admitted that she would gravitate towards some members because she identified with them and their context, and liked making comparisons with her own classes. Allie also described how she followed one course member’s contributions (a principal) because she respected his leadership perspective. By her third interview Allie was recognising recurring names from earlier courses, and she related to these participants as digital acquaintances. Although Allie acknowledged a general sense of connection to the online course community, she did not identify any particular relationships that stood out as being significant, apart from the short bursts of activity in groups where interaction was required (e.g., in one course where collaborative group tasks were set). This weak connection to the online community was shared by all of the participants with one or two exceptions. Wendy and Susan, two secondary ICT specialists, began their study in the same semester and developed a closer tie as they studied several consecutive courses, even though they had never met in person. While they felt connected to each other, this familiarity did not extend to other course members. Similarly, Karen recognised an online network resulting from an informal cohort following a similar study plan with developing connections over ensuing semesters. Overall, participants appreciated lecturers’ attempts to foster a sense of community but placed little importance on developing meaningful online connections. In spite of this, there was consensus that online contributions supported and initiated learning experiences for teachers and that cross-sector conversations promoted deeper consideration of ideas and theories.

Allie talked explicitly about her professional learning with her own students, telling them, “I talk about you all the time on this course, saying what we are up to.” She regularly introduced her class to new strategies or ideas which originated from her coursework, and she was able to point to examples on her classroom walls that bore evidence of this. The connections between Allie’s personal interest in ICT, her online study, and her teaching practice were clear. She deliberately embraced the new technologies being introduced into her school. It was clear that Allie incorporated new ideas and strategies in authentic ways, extending beyond the need to comply with assignment requirements.

When Allie shifted to her new job she adapted the course requirements to suit her new context even though she was not teaching a regular class. She was justifiably proud of one course-related project where she developed a website to introduce a special themed program on creative creatures.

I purposely picked something that I knew we could use for our holiday program, and our theme had already been set with “Seeing is believing”. I built—using the .EXE program—a website. It was our intro for our holiday program. I broke it down into four [modules] and looked at creatures, and myths and legends, and creatures in movies, creatures in stories, all that kind of stuff. And then from there [the children] would use tablets and draw. So, I used that website for the start of the program and I trialled it on some kids [from a previous school].

The finished website was well-structured, made excellent use of multimedia elements to engage students, and provided an enticing introduction to the planned program. Allie integrated her course-inspired ideas in other ways as she experimented with different strategies. In one example Allie developed a youth heritage project supported by Web 2.0 technologies to ensure that students whom she saw infrequently (once per week) could stay in touch with her and other project members via a wiki. The depth of Allie’s learning was evident in her reflections where she justified planning from theoretical perspectives and in an evaluative summary she presented to one online class via her own specially designed website. Not all of these activities were course requirements, and Allie’s enthusiasm for technology spurred her to experiment with new strategies and ideas in both her classroom and community learning centre contexts.

In the language of Wenger’s (1998) communities of practice social theory, Allie was a newcomer to the learning centre and was aware that she was still establishing herself, becoming familiar with the new culture, and gaining confidence in her new role. Allie was moving on an inward trajectory, from legitimate peripheral participation to a more established role in the organisation as she learnt more about its practices and expectations. When asked how she interacted with her colleagues and if she had opportunities to link her coursework into her new situation, she initially responded that she talked less to colleagues in her new role than she had in her previous job. However, as the interview progressed, this did not seem to be the case as Allie explained how she integrated some of her course activities and projects into the programs she was developing and how she worked with colleagues to do this. Her small team of new colleagues all had teaching backgrounds, and Allie would let her team leader know what she was doing and how her ideas might fit with the program. Later in the interview Allie compared her experiences working in the two different contexts.

Because my colleagues here, especially M my team leader, is always asking, “so what is it that you are taking in your online this time?”—like she does see that we will use it. Whereas with teaching last year, I don’t know, I mean some teachers knew I was taking online [study], but I don’t know if they saw that as an opportunity that they might use something that I was doing. Because it was very much, whatever I did, I just used in my class. It could have been shared a lot more now that I look back at it. . . . Whereas here I think whatever I am learning, it will be used. In future courses, I can see that happening.

Although she was a relative newcomer to the learning centre, Allie actively spanned the boundaries between study and work. Encouraged by her team leader, Allie acted as a broker introducing new strategies to enhance the existing repertoire and practice.

Allie’s experiences and examples were not dissimilar to those shared by other research participants. Her case is illustrative of the learning experiences encountered by teachers engaged in part-time online formal study while simultaneously working in teaching-related communities of practice. There was sound evidence, particularly from the school community subgroup where participants’ perspectives were independently endorsed by colleagues, that teachers made strong connections to their own classrooms, and there were numerous examples of strategies and theoretical approaches informing practice. These examples included using Web 2.0 tools for creative, collaborative, student-led activities; designing and implementing webquests; concept mapping and higher-order thinking strategies; inquiry learning and blended learning approaches; introducing learning management systems into the organisation; providing professional development sessions for colleagues; sharing readings and resources; and lastly, but significantly, implementing practitioner research projects within the wider school (e.g., ICT and creativity in junior classrooms; ICT to support spelling programs; LMS implementation in a secondary school; and the use of Web 2.0 tools to connect a kiwi conservation project to the classroom).

When school teachers engage in university courses for professional development, they are increasingly turning to online or blended learning as a means to combine work and study (Mandinach, 2005; Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia, & Jones, 2009; Roskos, Jarosewich, Lenhart, & Collins, 2007). Web-based technologies can improve access, equity, and quality of professional learning opportunities. Also, establishing online cohorts of teachers in courses can provide rich interactions regardless of location and teaching commitments (Harlen & Doubler, 2007; Robinson, 2008; Teemant, Smith, Pinnegar, & Egan, 2005). In addition, online or blended professional development may provide “real-time, ongoing, work-embedded support” (Dede, Ketelhut, Whitehouse, Breit, & McCloskey, 2009, p. 9); benefits associated with written asynchronous communication, which can enhance learning by allowing more time for reflection and more considered response; the potential of the online community to encourage the sharing of teachers’ reflections and experiences; and extended access to resources and expertise beyond the immediate school environment (Dede et al., 2009; Harlen & Doubler, 2007). Lieberman and Pointer-Mace (2010) discuss the potential of networked technologies and communities to make teaching practice public and the transformative power of sharing teachers’ knowledge. They highlight the value and impact of online connections, stating that “from more formal networks designed with particular purposes to informal grassroots connections, teacher professional learning is thriving online” (p. 86). Networked interactions allow teachers to share their own practice, rather than being the passive recipients of expert knowledge; such interactions provide opportunities for useful discourse related to practice. Laferrière, Lamon, and Chan (2006) similarly note that such technologies enable distributed cognition whereby teachers “create and improve knowledge of the community collectively” (p. 78).

This study showed that participants viewed the online interactions as useful but that, irrespective of their level of participation, they did not form strong connections with others in the online courses. There was evidence of sharing practices and understandings in the networked environment, but generally these were limited to the assessment and practicalities of completing the course. While the short duration of the courses (one 15-week semester) was a factor, teachers commonly found themselves in online classes with teachers from previous courses, which provided some sense of continuity but not enough to develop strong ties. Teachers identified superficial connections with others based around shared activities and a common understanding of roles and responsibilities in their school communities. The participants admitted gravitating towards “like-minded” course members but also recognised that different perspectives challenged their own thinking and prompted them to consider new possibilities. For example, secondary teachers noted that they didn’t have a great deal in common with their primary colleagues, but nonetheless several noted that they were inspired to try new pedagogical approaches after reading posts from primary teachers. Such behaviours may also be interpreted in the light of Gravenotter’s (1983) sociological theory of the strength of weak ties, whereby individuals benefit in various ways from their associations with acquaintances. While individuals are likely to have close ties with those who share similar world views and understandings, one advantage of weak ties is the opportunity to gain new information or resources via association with people beyond the ring of close relationships. Interestingly, and in alignment with Lave and Wenger’s (1991) understanding of what it means to be a broker, Gravenotter also notes that weak ties with acquaintances outside the circle of a close community may act as a network bridge and enable the diffusion of new ideas and practices between groups. Improved global communication systems and the ability to network virtually with others increase the potential to utilise weak connections in this way as seen within this study.

The participants blended the formal learning opportunities with their daily work as teachers. They constructed their own network of practice, selecting those they connected with in both online and school communities; they managed the level of interaction, particularly in the online environment where they were pragmatic about their time and purposeful in selecting those they responded to and whose work they read; and they aligned ideas, theories, strategies, and pedagogical approaches from the course with their own contexts, deciding which to implement and which to discard.

Teachers traversed the boundaries between work and study, managing their experiences of multimembership in ways that made sense to them personally and that aligned with the contextual demands and organisational cultures of their workplace environments. For example, some teachers had strong departmental communities and used these connections to strengthen and extend their learning experiences; some used their own learning to lead ICT development within their schools; others focused on their own classrooms and teaching practice; and some, like Allie, explicitly shared their own learning experiences with their students and included them in the ongoing exploration of new technologies and strategies for learning.

Participants became brokers and conduits between the online learning community and their own community of practice. While their own teaching changed as a result of their study, it was also clear from interviews with participants and their colleagues that ideas permeated beyond their own classrooms. The participants were able to lead discussions, support colleagues, share their research activities, and introduce new ideas in their syndicates and departments. These activities were explained and endorsed by the teaching colleagues who were interviewed in the research. Furthermore, even when participants were less overt about their study and focused more specifically on their own teaching practice and their own classrooms, their colleagues were cognisant of study-inspired innovations emerging through children’s work displayed on classroom walls and in presentations at assemblies.

The activities and perspectives of teachers in this study provided insight into the ways that individuals negotiate the formal and informal learning experiences in and between communities. The online learning community exhibited some characteristics of a functioning community of practice described by Wenger (1998), for example shared understandings and repertoire, sense of mutual engagement, and activities resembling joint enterprise. However, participants’ perspectives did not support a trajectory of engagement from the periphery to a more centrally connected position within the online community. Although some of the participants had completed six or seven online courses and were active participants in the online environment, they held only a nebulous sense of belonging to the community. Their pragmatic, purposeful approach to the online community suggests that their personal learning strategies may well reflect some of the characteristics of connectivist learning as described by Siemens (2005) and Downes (2006). Participants’ experiences and views harmonise with the following synopsis of connectivist theory.

The starting point of connectivism is the individual. Personal knowledge is comprised of a network, which feeds into organizations and institutions, which in turn feed back into the network, and then continue to provide learning to [the] individual. This cycle of knowledge development (personal to network to organization) allows learners to remain current in their field through the connections they have formed (Siemens, 2004, p. 5).

Siemens (2005) also suggests that weak ties, such as those exhibited by the participants in the online course community, are a valuable source of information within personal learning networks. Furthermore, he suggests that these tenuous or fleeting connections play an important role in prompting and supporting innovative practices as individuals are exposed to new ideas from beyond their familiar network of practice.

A connectivist perspective provides a useful lens to interpret how working professionals (like teachers) access and interact with academic and scholarly expertise in universities and simultaneously with peers in different locations as well as with colleagues in their own workplace. The increasing use of Web 2.0 tools alongside institutional learning management systems enables extended connections with the wider educational community and other interested participants. For example, a course lecturer links to a well-respected national ICT leader’s blog, or the course participants themselves contribute to online discussion forums, share work for peer review, or create publicly available artefacts online using Prezi, VoiceThread, etc. Learners are central to the process as they make the cognitive, social, and practical connections across networks enabled by technology.

It was clear in this research that the participants took control of their own online learning experiences. This sense of autonomy was evident in their choices and level of interaction online and offline and in the way they connected the theoretical and practical ideas from coursework to their own work contexts. They were focused on their own learning needs and were not looking for social engagement or sustained connections with others in the online environment. Their pragmatic online connections served a purpose, diversifying their networks and opening up new possibilities for learning, but these connections were different to the sustained interactions which occurred in their communities of practice. Teachers appeared to connect, blend, and design their own learning experiences in ways that dismissed issues of transfer and instead demonstrated permeability and connectivity between the two communities.

For the participants, online professional development provided opportunities to integrate their experiences as learners and teachers. Their experiences suggest there is considerable potential for online learning communities to support professional learning for teachers within schools. A key to realising this potential will be the redesign of online courses to encourage participants to develop their own networks of practice within and beyond the course parameters, accepting that weak online ties offer valuable learning opportunities and facilitating the strong links teachers often have within their school communities.

Such redesign will need to value learning that is synchronised with, and situated in, professional practice; encourage the often invisible interactions that learners have with those outside the formal course structure; promote the sharing of work and school-based examples within the online environment (especially cross-sector interaction); and facilitate critical reflection focusing on the links between theory and practice and between new and existing beliefs, attitudes, and practices.

Above all, effective redesign will embrace creative curricula approaches to enable participants to select and adapt learning activities to align with their own professional contexts. Providing flexibility and choice in relation to course content, assessment, and learning activities requires participants to be independent learners, prepared to take responsibility for interpreting, translating, and connecting their learning experiences to professional contexts. Inevitably this means less emphasis on standard coursework and assessment and increased variety in participant activity, with implications for lecturers to scaffold the processes and support multiple projects within a common framework. Increased flexibility and choice for learners should lead to greater opportunities for connections between communities from the perspective of the learner.

There are further possibilities for research on the effect of intermittent and short-term connections afforded by professional learning networks, including those related to formal settings, such as online qualifications, and the informal connections offered via social networking tools.

Dr. Elizabeth Stacey provided valuable advice and support during the conduct of this research project.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

Conrad, D. L. (2008). From community to community of practice: Exploring the connection of online learners to informal learning in the workplace. American Journal of Distance Education, 22, 3–23.

Cousin, G., & Deepwell, F. (2005). Designs for network learning: A communities of practice perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 30(1), 57–66.

Dede, C., Ketelhut, D. J., Whitehouse, P., Breit, L., & McCloskey, E. M. (2009). A research agenda for online teacher professional development. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 8–19.

Downes, S. (2006). Learning networks and connective knowledge. Instructional Technology Forum, 28. Retrieved from http://it.coe.uga.edu/itforum/paper92/paper92.html.

Dyke, M., Conole, G., Ravenscroft, A., & de Freitas, S. (2007). Learning theory and its application to e-learning. In G. Conole & M. Oliver (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives in e-learning research: Themes, methods and impact on practice (pp. 82–97). London: Routledge.

Dysthe, O. (2002). The learning potential of a web-mediated discussion in a university course. Studies in Higher Education, 27(3), 339–352.

Edwards, S., & Romeo, G. (2003). Interlearn: An online teaching and learning system developed at Monash University. Paper presented at the World Conference on e-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare and Higher Education (ELEARN) 2003, Phoenix, AZ.

Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61–72.

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133–148.

Geer, R. (2005). Imprinting and its impact on online learning environments. Paper presented at the Ascilite 2005: Balance, Fidelity and Mobility and Maintaining the Momentum, QUT, Brisbane, Queensland.

Goodfellow, R. (2005). Virtuality and the shaping of educational communities. Education, Communication & Information, 5(2), 113–129.

Gravenotter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisted. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233.

Hansmann, S. (2006). Qualitative case method and web-based learning: The application of qualitative research methods to the systematic evaluation of web-based learning assessment results. In B. L. Mann (Ed.), Selected styles in web-based educational research (pp. 91–110). Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Harlen, W., & Doubler, S. J. (2007). Researching the impact of online professional development for teachers. In R. Andrews & C. Haythornthwaite (Eds.), The Sage handbook of e-learning research (pp. 466–486). London: Sage Publications.

Henri, F., & Pudelko, B. (2003). Understanding and analysing activity and learning in virtual communities. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 19(4), 474–487.

Henri, F., Charlier, B., Daele, A., & Pudelko, B. (2003). Evaluation for knowledge: An approach to supporting the quality of learners' community in higher education. In G. Davies & E. Stacey (Eds.), Quality Education @ a Distance; IFIP TC3/WG3.6 Working Conference on Quality Education @ a Distance, February 3–6, 2003, Geelong, Australia (pp. 211–220). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Janetzko, D. (2008). Nonreactive data collection on the Internet. In N. Fielding, R. M. Lee & G. Blank (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of online research methods (pp. 161–174). London: Sage Publications.

Laferrière, T., Lamon, M., & Chan, C. K. K. (2006). Emerging e-trends and models in teacher education and professional development. Teaching Education, 17(1), 75–90.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lieberman, A., & Pointer-Mace, D. (2010). Making practice public: Teacher learning in the 21st century. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 77–88.

Mandinach, E. B. (2005). The development of effective evaluation methods for e-learning: A concept paper and action plan. Teachers College Record, 107(8), 1814–1835.

Maor, D., & Volet, S. (2007). Engagement in professional online learning: A situative analysis of media professionals who did not make it. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(1), 95–117.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2007). Building online learning communities: Effective strategies for the virtual classroom (2nd ed. of Building learning communities in cyberspace). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pena-Shaff, J., & Nicholls, C. (2004). Analyzing computer interactions and meaning construction in computer bulletin board discussions. Computers and Education, 42(3), 243–265.

Robinson, B. (2008). Using distance education and ICT to improve access, equity and the quality in rural teachers' professional development in China. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(1), 1–17.

Roskos, K., Jarosewich, T., Lenhart, L., & Collins, L. (2007). Design of online teacher professional development in a statewide Reading First professional development system. Internet and Higher Education, 10, 173–183.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/networks.htm

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm

Slevin, J. (2008). E-learning and the transformation of social interaction in higher education. Learning, Media, & Technology, 33(2), 115–126.

Sorensen, E. K. (2005). Networked eLearning and collaborative knowledge building: Design and facilitation. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 4(4), 446–455.

Teemant, A., Smith, M. E., Pinnegar, S., & Egan, M. W. (2005). Modeling sociocultural pedagogy in distance education. Teachers College Record, 107(8), 1675–1698.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, B. G., Ludwig-Hardman, S., Thornam, C. L., & Dunlap, J. C. (2004). Bounded community: Designing and facilitating learning communities in formal courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5(3), 1–22.

Yin, R. K. (2006). Case study methods. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli & P. B. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 111–122). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.