Terry Anderson and Jon Dron

Athabasca University, Canada

This paper defines and examines three generations of distance education pedagogy. Unlike earlier classifications of distance education based on the technology used, this analysis focuses on the pedagogy that defines the learning experiences encapsulated in the learning design. The three generations of cognitive-behaviourist, social constructivist, and connectivist pedagogy are examined, using the familiar community of inquiry model (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) with its focus on social, cognitive, and teaching presences. Although this typology of pedagogies could also be usefully applied to campus-based education, the need for and practice of openness and explicitness in distance education content and process makes the work especially relevant to distance education designers, teachers, and developers. The article concludes that high-quality distance education exploits all three generations as determined by the learning content, context, and learning expectations.

Keywords: Distance education theory

Distance education, like all other technical–social developments, is historically constituted in the thinking and behavioural patterns of those who developed, tested, and implemented what were once novel systems. The designs thus encapsulate a worldview (Aerts, Apostel, De Moor, Hellemans, Maex, Van Belle, & Van Der Veken, 1994) that defines its epistemological roots, development models, and technologies utilized, even as the application of this worldview evolves in new eras. In this paper, we explore distance education systems as they have evolved through three eras of educational, social, and psychological development. Each era developed distinct pedagogies, technologies, learning activities, and assessment criteria, consistent with the social worldview of the era in which they developed. We examine each of these models of distance education using the community of inquiry (COI) model (Arbaugh, 2008; Garrison, 2009; Garrison, Archer, & Anderson, 2003) with its focus on teaching, cognitive, and social presence.

Given the requirement for distance education to be technologically mediated in order to span the geographic and often temporal distance between learners, teachers, and institutions, it is common to think of development or generations of distance education in terms of the technology used to span these distances. Thus distance education theorists (Garrison, 1985; Nipper, 1989), in a somewhat technologically deterministic bent, have described and defined distance education based on the predominate technologies employed for delivery. The first generation of distance education technology was by postal correspondence. This was followed by a second generation, defined by the mass media of television, radio, and film production. Third-generation distance education (DE) introduced interactive technologies: first audio, then text, video, and then web and immersive conferencing. It is less clear what defines the so-called fourth- and even fifth-generation distance technologies except for a use of intelligent data bases (Taylor, 2002) that create “intelligent flexible learning” or that incorporate Web 2.0 or semantic web technologies. It should be noted that none of these generations has been eliminated over time; rather, the repertoire of options available to DE designers and learners has increased. Similarly, all three models of DE pedagogy described below are very much in existence today.

Many educators pride themselves on being pedagogically (as opposed to technologically) driven in their teaching and learning designs. However, as McLuhan (1964) first argued, technologies also influence and define the usage, in this case the pedagogy instantiated in the learning and instructional designs. In an attempt to define a middle ground between either technological or pedagogical determinism, we’ve previously written (Anderson, 2009) about the two being intertwined in a dance: the technology sets the beat and creates the music, while the pedagogy defines the moves. To some extent, our pedagogical processes may themselves be viewed as technologies (Dron & Anderson, 2009), albeit of a softer nature than the machines, software, postal systems, and so on that underpin distance education. Some technologies may embody pedagogies, thereby hardening them, and it is at that point that they, of necessity, become far more influential in a learning design, the leaders of the dance rather than the partners. For example, a learning management system that sees the world in terms of courses and content will strongly encourage pedagogies that fit that model and constrain those that lack content and do not fit a content-driven course model. The availability of technologies to support different models of learning strongly influences what kinds of model can be developed; if there were no means of two-way communication, for example, it would prevent the development of a pedagogy that exploited dialogue and conversation and encourage the development of a pedagogy that allowed the learner and the course content to be self-contained.

In this paper, we introduce a simple typology in which distance education pedagogies are mapped into three distinct generations. Since the three arose in different eras and in chronological order, we’ve labeled them from first to third generation, but as in generations of technology, none of these three pedagogical generations has disappeared, and we will argue that all three can and should be effectively used to address the full spectrum of learning needs and aspirations of 21st century learners.

Cognitive and behaviourist (CB) pedagogies focus on the way in which learning was predominantly defined, practiced, and researched in the latter half of the 20th century. Behavioural learning theory begins with notions of learning which are generally defined as new behaviours or changes in behaviours that are acquired as the result of an individual’s response to stimuli. Note in this definition the focus on the individual and the necessity for measuring actual behaviours and not attitudes or capacities. Major behaviourist learning theorists include American psychologists Edward Watson, John Thordike, and B.F. Skinner. These theoretical ideas led directly to instructional designs and interventions such as the Keller Plan (Keller & Sherman, 1974), computer-assisted instruction, and instructional systems designs. For example, Gagne’s (1965) events of instruction proceed through linear and structured phases, including to

1. gain learners’ attention,

2. inform learner of objectives,

3. stimulate recall of previous information,

4. present stimulus material,

5. provide learner guidance,

6. elicit performance,

7. provide feedback,

8. assess performance,

9. enhance transfer opportunities.

Behaviourist notions have been especially attractive for use in training (as opposed to educational) programs as the learning outcomes associated with training are usually clearly measured and demonstrated behaviourally. From the behaviourist tradition emerged the cognitive revolution, beginning in the late 1950s (Miller, 2003). Cognitive pedagogy arose partially in response to a growing need to account for motivation, attitudes, and mental barriers that may only be partially associated or demonstrated through observable behaviours. Also important, cognitive models were based on a growing understanding of the functions and operations of the brain and especially of the ways in which computer models were used to describe and test learning and thinking. Much research using this model proceeded from empirical testing of multimedia effects, cognitive overload, redundancy, chunking, short- and long-term memory, and other mental or cognitive processes related to learning (Mayer, 2001). Although learning was still conceived of as an individual process, its study expanded from an exclusive focus on behaviour to changes in knowledge or capacity that are stored and recalled in individual memory. The tradition continues with the successful application of experimentally verified methods like spaced learning (Fields, 2005) and applications of brain science, as well as more dubious, scientifically unsound and unverifiable learning style theories (Coffield, Moseley, Hall, & Ecclestone, 2004) that achieved popularity towards the end of the twentieth century and that still hold sway in many quarters today. The locus of control in a CB model is very much the teacher or instructional designer. Such theories provide models of learning that are directly generative of models of teaching.

It is notable that such models gained a foothold in distance education at a time when there were limited technologies available that allowed many-to-many communication. Teleconferencing was perhaps the most successful means available but came with associated costs and complexity that limited its usefulness. The postal service and publication or redistribution of messages was very slow, expensive, and limited in scope for interactivity. Methods that relied on one-to-many and one-to-one communication were really the only sensible options because of the constraints of the surrounding technologies.

Cognitive presence is the means and context through which learners construct and confirm new knowledge. In cognitive–behaviourist models of learning, cognitive presence is created through structured processes in which learners’ interest is stimulated, informed by both general and specific cases of overriding principles and then tested and reinforced for the acquisition of this knowledge. CB models of distance education pedagogy stress the importance of using an instructional systems design model where the learning objectives are clearly identified and stated and exist apart from the learner and the context of study. Later developments in cognitive theory have attempted to design learning materials in ways that maximized brain efficiency and effectiveness by attending to the types, ordering, timing, and nature of learning stimulations.

What most defined the cognitive-behavioural generation of distance education was an almost total absence of social presence. Learning was thought of as an individual process, and thus it made little difference if one was reading a book, watching a movie, or interacting with a computer-assisted learning program by oneself or in the company of other learners. This focus on individualized learning resulted in very high levels of student freedom (space and pace) and fitted nicely with technologies of print packages, mass media (radio and television), and postal-correspondence interaction. It is also interesting to note the backlash against distance education that arose amongst traditional campus-based academics, partially in reaction to this individualized affordance. This suspicion continues today (Garrison, 2009), though 30 years of research has yet to show differences in learning outcomes between learning designs with high or low levels of social presence, that is if one confines the definition of learning to the CB notions of acquisition of pre-specified facts and concepts.

Teaching presence in CB models was also reduced or at least radically reconstructed in many forms of CB distance education. In its earliest instantiation as correspondence education, the teacher had only their words on printed text to convey their presence. Holmberg (1989) described a style of writing that he called guided didactic interaction which, through personalization and a conversational writing style, was supposed to transmit the personality and caring concern of the teacher or author. Later technologies allowed voice (audio) and body language of the teacher (video) to be transmitted through television, film, and multimedia-based educational productions. Despite the general absence of the teacher in these CB pedagogies, one cannot discount the teaching presence that potentially could be developed through one-to-one written correspondence, telephone conversation, or occasional face-to-face interaction between teacher and student, as amply demonstrated in the movie and play versions of Educating Rita. Despite this potential, the teaching-presence role is confused in that the learning package that instantiates CB pedagogical models is supposed to be self-contained and complete, requiring only teacher–learner interaction for marking and evaluation. No doubt some distance education students using this model do experience high levels of teaching presence, but for many, teaching presence is only mediated through text and recorded sound and images. This reduction of the role and importance of the teacher further fueled resentment by traditional educators against the CB model of distance education and gave rise to the necessity of creating single-mode institutions which could develop educational models free from the constraint of older models of classroom-based and teacher-dominated education.

To summarize, CB models defined the first generation of individualized distance education. They maximized access and student freedom, and were capable of scaling to very large numbers at significantly lower costs than traditional education, as demonstrated by the successful mega-universities (Daniel, 1996). However, these advantages were accompanied by the very significant reductions in teaching, social presence, and formal models of cognitive presence, reductions that have come under serious challenge since the latter decades of the 20th century. While appropriate when learning objectives are very clear, CB models avoid dealing with the full richness and complexity of humans learning to be, as opposed to learning to do (Vaill, 1996). People are not blank slates but begin with models and knowledge of the world and learn and exist in a social context of great intricacy and depth.

While there is a tradition of cognitive-constructivist thinking that hinges on personal construction of knowledge, largely developed by Piaget and his followers (Piaget, 1970), the roots of the constructivist model most commonly applied today spring from the work of Vygotsky and Dewey, generally lumped together in the broad category of social constructivism. Social-constructivist pedagogies, perhaps not coincidently, developed in conjunction with the development of two-way communication technologies. At this time, rather than transmitting information, technology became widely used to create opportunities for both synchronous and asynchronous interactions between and among students and teachers. Michael Moore’s famous theory of transactional distance (1989) noted the capacity for flexible interaction to substitute for structure in distance education development and delivery models. A number of researchers noted the challenges of getting the mix of potential interactions right (Anderson, 2003; Daniel & Marquis, 1988). Social-constructivist pedagogy acknowledges the social nature of knowledge and of its creation in the minds of individual learners. Teachers do not merely transmit knowledge to be passively consumed by learners; rather, each learner constructs means by which new knowledge is both created and integrated with existing knowledge. Although there are many types of social constructivism (see Kanuka & Anderson, 1999), all the models have more or less common themes, including the importance of

The need for social construction and representation, for multiple perspectives, and for awareness that knowledge is socially validated demanded the capacity for distance education to be a social activity as well as the development of cohort, as opposed to individual study, organizational models of instruction. As Greenhow, Robelia, and Hughes (2009) and others have argued, learning is located in contexts and relationships rather than merely in the minds of individuals.

The locus of control in a social-constructivist system shifts somewhat away from the teacher, who becomes more of a guide than an instructor, but who assumes the critical role of shaping the learning activities and designing the structure in which those activities occur. Social-constructivist theories are theories of learning that are less easily translated into theories of teaching than their CB forebears.

It is notable that social-constructivist models only began to gain a foothold in distance education when the technologies of many-to-many communication became widely available, enabled first by email and bulletin boards, and later through the World Wide Web and mobile technologies. While such models had been waiting in the wings for distance education since Dewey or earlier, their widespread use and adoption was dependent on the widespread availability of workable supporting technologies.

Constructivists emphasize the importance of knowledge having individual meaning. Thus, cognitive presence is located in as authentic a context as possible, which resonates with distance education, much of which takes place in the workplace and other real-world contexts outside of formal classrooms. Cognitive presence also assumes that learners are actively engaged, and interaction with peers is perhaps the most cost-effective way to support cognitive presence (not requiring the high costs of simulations, computer-assisted learning programming, or media production). Cognitive presence, for constructivists, also exploits the human capacity for role modeling (Bandura, 1977), imitation (Warnick, 2008), and dialogic inquiry (Wegerif, 2007). Thus, Garrison (1997) and others could argue that constructivist-based learning with rich student-student and student-teacher interaction constituted a new, “post-industrialist era” of distance education. However, this focus on human interactions placed limits on accessibility and produced more costly models of distance education (Annand, 1999). It remains challenging to apply learning where it can blossom into application and thus demonstrate true understanding.

Social interaction is a defining feature of constructivist pedagogies. At a distance, this interaction is always mediated, but nonetheless, it is considered to be a critical component of quality distance education (Garrison, 1997). Much research has been undertaken to prove that quality interaction and subsequent social presence can be supported in both synchronous and asynchronous models of distance education. More recent developments in immersive technologies, such as Second Life, allow gestures, costumes, voice intonation, and other forms of body language that may provide enhancements to social presence beyond those experienced face-to-face (McKerlich & Anderson, 2007). It is likely, as learners become more acclimatized and skilled in using ever-present mobile communications and embedded technologies, that barriers associated with a lack of social presence will be further reduced, allowing constructivist models to thrive.

Kanuka and Anderson (1999) argued that in constructivist modes of distance education, “the educator is a guide, helper, and partner where the content is secondary to the learning process; the source of knowledge lies primarily in experiences.” Given this critical role, one can see the importance of teaching presence within constructivist models. Teaching presence extends beyond facilitation of learning to choosing and constructing educational interventions and to providing direct instruction when required. The requirements for high levels of teaching presence make the scaling of constructivist distance education models problematic (Annand, 1999), with few classes ever expanding beyond the 30–40 student cohort. Assessment in constructivist models is much more complicated than in behaviourist models, as David Jonassen (1991) has argued: “Evaluating how learners go about constructing knowledge is more important from a constructivist viewpoint than the resulting product” (p. 141). Thus, teaching presence in constructivist pedagogical models focuses on guiding and evaluating authentic tasks performed in realistic contexts.

Constructivist distance education pedagogies moved distance learning beyond the narrow type of knowledge transmission that could be encapsulated easily in media through to the use of synchronous and asynchronous, human communications-based learning. Thus, Garrison and others argue that the rich student-student and student-teacher interaction could be viewed as a “post-industrialist era” of distance education. However, Annand views the focus on human interaction as placing limits on accessibility and producing more costly models of distance education. Ironically, constructivist models of distance education began to share many of the affordances and liabilities of campus-based education, with potential for teacher domination, passive lecture delivery, and restrictions on geographic and temporal access.

The third generation of distance-education pedagogy emerged recently and is known as connectivism. Canadians George Siemens (Siemens, 2005a, 2005b, 2007) and Stephen Downes (2007) have written defining connectivist papers, arguing that learning is the process of building networks of information, contacts, and resources that are applied to real problems. Connectivism was developed in the information age of a networked era (Castells, 1996) and assumes ubiquitous access to networked technologies. Connectivist learning focuses on building and maintaining networked connections that are current and flexible enough to be applied to existing and emergent problems. Connectivism also assumes that information is plentiful and that the learner’s role is not to memorize or even understand everything, but to have the capacity to find and apply knowledge when and where it is needed. Connectivism assumes that much mental processing and problem solving can and should be off-loaded to machines, leading to Siemens’ (2005) contentious claim that “learning may reside in non-human appliance.” Thus, connectivism places itself within the context of actor-network theory with its identification of the indiscriminate and overlapping boundaries between physical objects, social conventions, and hybrid instantiations of both, as defined by their initial and evolved application in real life (Latour, 1993).

It is noteworthy that connectivist models explicitly rely on the ubiquity of networked connections between people, digital artifacts, and content, which would have been inconceivable as forms of distance learning were the World Wide Web not available to mediate the process. Thus, as we have seen in the case of the earlier generations of distance learning, technology has played a major role in determining the potential pedagogies that may be employed.

Connectivist cognitive presence begins with the assumption that learners have access to powerful networks and, as importantly, are literate and confident enough to exploit these networks in completing learning tasks. Thus, the first task of connectivist education involves exposing students to networks and providing opportunities for them to gain a sense of self-efficacy in networked-based cognitive skills and the process of developing their own net presence. Connectivist learning happens best in network contexts, as opposed to individual or group contexts (Dron & Anderson, 2007). In network contexts, members participate as they define real learning needs, filter these for relevance, and contribute in order to hone their knowledge creation and retrieval skills. In the process, they develop networks of their own and increase their developing social capital (Davies, 2003; Phillips, 2002). The artifacts of connectivist learning are usually open, accessible, and persistent. Thus, distance education interaction moves beyond individual consultations with faculty (CB pedagogy) and beyond the group interactions and constraints of the learning management systems associated with constructivist distance-education pedagogy. Cognitive presence is enriched by peripheral and emergent interactions on networks, in which alumni, practicing professionals, and other teachers are able to observe, comment upon, and contribute to connectivist learning.

Connectivist learning is based as much upon production as consumption of educational content. Thus, tools and skills of production (or produsage, as Bruns [2008] refers to the means of production when producers are also users of the resources). The results of this produsage are archives, learning objects, discussion transcripts, and resources produced by learners in the process of documenting and demonstrating their learning. These dialogic encounters become the content that learners and teachers utilize and collaboratively create and recreate. Connectivist cognitive presence is enhanced by the focus on reflection and distribution of these reflections in blogs, twitter posts, and multimedia webcasts.

Connectivist pedagogy stresses the development of social presence and social capital through the creation and sustenance of networks of current and past learners and of those with knowledge relevant to the learning goals. Unlike group learning, in which social presence is often created by expectation and marking for participation in activities confined to institutional time frames, social presence on networks tends to be busy as topics rise and fall in interest. The activities of learners are reflected in their contributions to wikis, Twitter, threaded conferences, Voicethreads, and other network tools. Further, social presence is retained and promoted through the comments, contributions, and insights of students who have previously engaged in the course and that persist as augmentable archives to enrich network interactions for current students. Connectivist learning is also enhanced by the stigmergic knowledge of others and the signs that they leave as they navigate through learning activities. The activities, choices, and artifacts left by previous users are mined through network analytics and presented as guideposts and paths to knowledge that new users can follow (Dron, 2006). In this way, the combination of traces of people’s actions and activities generate an emergent collective, which may be seen as a distinctive individual in itself, both greater and lesser than the sum of its parts: it is a socially constituted entity that is, despite this, soulless, a reflection of the group mind that influences but does not engage in dialogue (Dron & Anderson, 2009).

As in constructivist learning, teaching presence is created by the building of learning paths and by design and support of interactions, such that learners make connections with existing and new knowledge resources. Unlike earlier pedagogies, the teacher is not solely responsible for defining, generating, or assigning content. Rather, learners and teacher collaborate to create the content of study, and in the process re-create that content for future use by others. Assessment in connectivist pedagogy combines self-reflection with teacher assessment of the contributions to the current and future courses. These contributions may be reflections, critical comments, learning objects and resources, and other digital artifacts of knowledge creation, dissemination, and problem solving. Teaching presence in connectivist learning environments also focuses on teaching by example. The teachers’ construction of learning artifacts, critical contributions to class and external discussion, capacity to make connections across discipline and context boundaries, and the sum of their net presence serve to model connectivist presence and learning. A final stress to teaching presence is the challenge presented by rapidly changing technologies. No one is current on all learning and communications applications, but teachers are often less competent and have less self-efficacy; thus, connectivist learning includes learners teaching teachers and each other, in conjunction with teachers aiding the connectivist learning of all.

Learning in connectivist space is, paradoxically, plagued by a lack of connection. CB models provide a strong structure to learning that makes explicit the path to be taken to knowledge. When done well, a cognitivist or behaviourist approach helps the learner to take a guided path towards a specific goal. Constructivist models still place an emphasis on scaffolding, albeit in a manner that is more conducive to meeting individual needs and contexts. What they lose in structure, they make up for in dialogue, with social-constructivist approaches (especially the Vygotsky-influenced variety), relying heavily on negotiation and mediation to help the learner from one state of knowledge to the next. In connectivist space, structure is unevenly distributed and often emergent, with that emergence seldom leading to structure that is optimally efficient for achieving learning goals.

Connectivist approaches used in a formal course setting, where top-down structure is imposed over the bottom-up emergent connections of the network, often rely heavily on foci that are typically provided by charismatic and popular network leaders. For example, David Wiley’s paradigmatic Open Edu 2008 (http://opencontent.org/wiki/index.php?title=Intro_Open_Ed_Syllabus) and the highly acclaimed and emblematic CCK08 provided by George Siemens and Stephen Downes (Downes, 2008) were both notably run by network leaders with many followers. This is not a coincidence: Such people occupy highly connected nodes in their networks and can encourage a sufficiently large population to engage so that there is continued activity even when the vast majority does not engage regularly. Even then, learners often yearn for a more controlled environment (Mackness, Mak, & Wiliams, 2010). When scaled down and superimposed over a formal teaching pattern, connectivist approaches require a great deal of energy on the part of the central connector to actively maintain the network, and it is a common complaint that students at least start by feeling lost and confused in a connectivist setting (Dron & Anderson, 2009; Hall, 2008). This is only partly due to difficulties in learning multiple technologies and navigating cyberspace, although this aspect can be an important issue (McLoughlin & Lee, 2008). The distributed nature and inherent fuzziness of goals, beginnings, and endings implied by a connectivist approach often fit poorly with a context in which students are taking more formal and traditional courses that use a constructivist and or a cognitive-behaviourist model. Furthermore, as Kop and Hill (2008) observe, not all learners have sufficient autonomy in a given area to be able or willing to exercise the control needed in such an environment. Cognitive-behaviourist models are most notably theories of teaching and social–constructivist models are more notably theories of learning, but both still translate well into methods and processes for teaching. Connectivist models are more distinctly theories of knowledge, which makes them hard to translate into ways to learn and harder still to translate into ways to teach. Indeed, the notion of a teacher is almost foreign to the connectivist worldview, except perhaps as a role model and fellow node (perhaps one more heavily weighted or connected) in a network.

While a great many speculative and theoretical papers have been written on the potential of connectivism, most reports of experience so far are equivocal and, to cater to diverse learner needs, there is a clear need for a richer means of establishing both networked and personal learning environments that offer control when needed in both pedagogical and organizational terms. The crowd can be a source of wisdom (Surowiecki, 2005) but can equally be a source of stupidity (Carr, 2010), with processes like preferential attachment that are as capable of leading to the Matthew Principle (where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer) and rampant bandwagon effects as to enabling effective, connected learning.

We have seen how different models of teaching and learning have evolved when the technological affordances and climate were right for them. Cognitive-behaviourist pedagogical models arose in a technological environment that constrained communication to the pre-Web, one-to-one, and one-to-many modes; social–constructivism flourished in a Web 1.0, many-to-many technological context; and connectivism is at least partially a product of a networked, Web 2.0 world. It is tempting to speculate what the next generation will bring. Some see Web 3.0 as being the semantic Web, while others include mobility, augmented reality, and location awareness in the mix (Hendler, 2009). All of these are likely to be important but may not be sufficient to bring about a paradigmatic change of the sorts we have seen in earlier generations of networked systems because the nature and mode of communication, though more refined, will not change much with these emerging technologies. We see a different paradigm emerging. As concerns about privacy mount and we come to adopt a more nuanced approach to connections and trust, our networks are bound to become more variegated and specialized. It is already becoming clear that connectivist approaches must become more intelligent in enabling people to connect to and discover sources of knowledge. Part of that intelligence will come from data-mining and analytics, but part will come from the crowd itself.

Another notable trend is towards more object-based, contextual, or activity-based models of learning. It is not so much a question of building and sustaining networks as of finding the appropriate sets of things and people and activities. CloudWorks, a product of the OU-UK, is an example of this new trend, in which objects of discourse are more important than, or at least distinct from, the networks that enable them (Galley, Conole, Dalziel, & Ghiglione, 2010). When we post a message to a public space like CloudWorks, a blog, or a microblog (e.g., Twitter), much of the time the post is not addressed or customized to a network of known entities but to an unknown set of people who we hope will be interested in what we have to say, typically defined through tags, profile fields, or hashtags. The next step in this cycle would seem to be, logically, to enable those sets to talk back to us: to find us, guide us, and influence our learning journeys. This represents a new and different form of communication, one in which the crowd, composed of multiple intelligences, behaves as an intentional single entity. Such set-driven computing is already perhaps one of the most common ways that learning is supported online: The PageRank algorithm behind a Google search works in exactly this way, taking multiple intelligent choices and combining them to provide ranked search results (Brin & Page, 2000). Wikipedia, though partially a farmed process, includes many crowd-based or collective elements to help others guide our learning. Amazon recommends books for us, using complex, collaborative filtering algorithms that use the crowd as their raw materials. In each case, it is not individuals, groups, or networks that help us to learn but a faceless intelligence that is partly made of human actions, partly of a machine’s.

We and others have described these entities in the past as collectives (Segaran, 2007). Despite the ubiquity of such systems, what still remains unclear is how best to exploit them in learning. However, it seems at least possible that the next generation of distance education pedagogy will be enabled by technologies that make effective use of collectives.

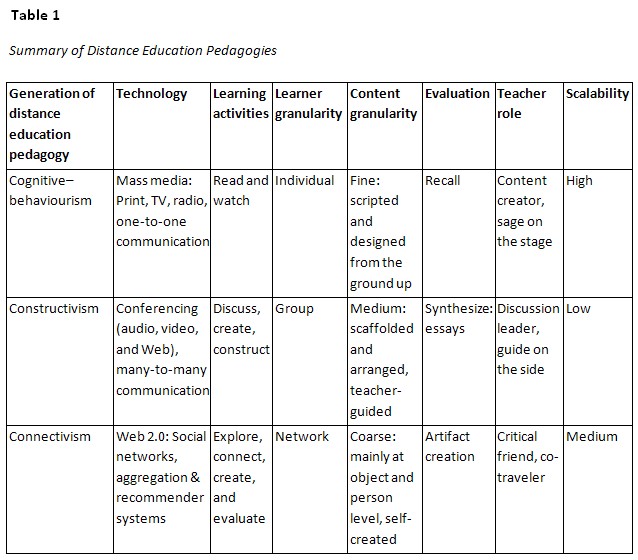

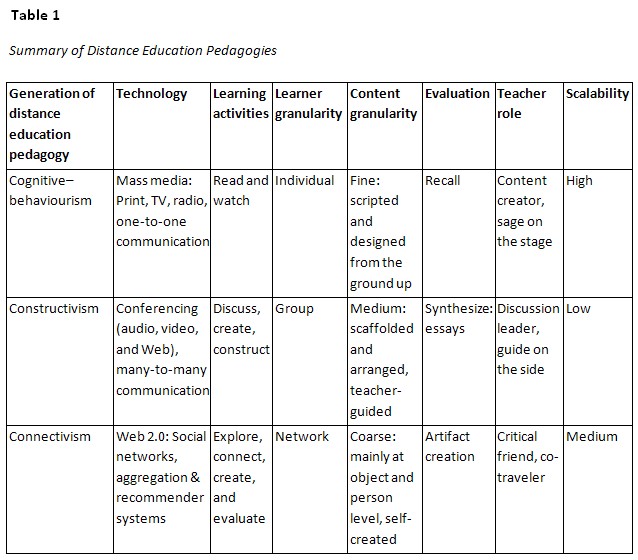

Distance education has evolved through many technologies and at least three generations of pedagogy, as described in this paper. No single generation has provided all the answers, and each has built on foundations provided by its predecessors rather than replacing the earlier prototype (Ireland, 2007). To a large extent, the generations have evolved in tandem with the technologies that enable them: As new affordances open out, it becomes possible to explore and capitalize on different aspects of the learning process. For each mode of engagement, different types of knowledge, learning, and contexts must be applied and demand that distance educators and students be skilled and informed to select the best mix(es) of both pedagogy and technology. Although the prime actors in all three generations remain the same—teacher, student, and content—the development of relationships among these three increases from the critical role of student–student interaction in constructivism to the student–content interrelationship celebrated in connectivist pedagogies, with their focus on persistent networks and user-generated content. The popular community-of-inquiry model, with its focus on building and sustaining cognitive, social, and teaching presence, can be a useful heuristic in selecting appropriate pedagogies. Table 1 below summarizes these features and provides an overview and examples of both similarities and differences among them.

We conclude by arguing that all three current and future generations of DE pedagogy have an important place in a well-rounded educational experience. Connectivism is built on an assumption of a constructivist model of learning, with the learner at the centre, connecting and constructing knowledge in a context that includes not only external networks and groups but also his or her own histories and predilections. At a small scale, both constructivist and connectivist approaches almost always rely to a greater or lesser degree on the availability of the stuff of learning, much of which (at least, that which is successful in helping people to learn) is designed and organized on CB models. The Web sites, books, tutorial materials, videos, and so on, from which a learner may learn, all work more or less effectively according to how well they enable the learner to gain knowledge. Even when learning relies on entirely social interactions, the various parties involved may communicate knowledge more or less effectively. It is clear that whether the learner is at the centre or part of a learning community or learning network, learning effectiveness can be greatly enhanced by applying, at a detailed level, an understanding of how people can learn more effectively: Cognitivist, behaviourist, constructivist, and connectivist theories each play an important role.

Aerts, D., Apostel, L., De Moor, B., Hellemans, S., Maex, E., Van Belle, H., & Van Der Veken, J. (1994). Worldviews: From fragmentation to integration. Brussels, Belgium: VUB Press. Retrieved from http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/clea/reports/worldviewsbook.html.

Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right: An updated and theoretical rationale for interaction. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 4(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/149/708.

Anderson, T. (2009). The dance of technology and pedagogy in self-paced distance education. Paper presented at the 17th ICDE World Congress, Maastricht. Retrieved from http://auspace.athabascau.ca:8080/dspace/bitstream/2149/2210/1/The%20Dance%20of%20technology%20and%20Pedagogy%20in%20Self%20Paced%20Instructions.docx.

Annand, D. (1999). The problem of computer conferencing for distance-based universities. Open Learning, 14(3), 47–52.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2008). Does the community of inquiry framework predict outcomes in online MBA courses? The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(2). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/490.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

Brin, S., & Page, L. (2000). The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Retrieved from http://www-db.stanford.edu/pub/papers/google.pdf.

Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: From production to produsage. New York, NY: Lang.

Carr, N. (2010). The shallows: What the Internet is doing to our brains. New York, NY: Norton.

Castells, M. (1996). The Information Age: Economy, society and culture: The rise of the networked society (Vol. 1). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. London: Learning and Skills Research Centre.

Daniel, J. (1996). Mega-universities and knowledge media: Technology strategies for higher education. London: Kogan Page.

Daniel, J., & Marquis, C. (1988). Interaction and independence: Getting the mix right. In D. Sewart, D. Keegan & B. Holmberg (Eds.), Distance education: International perspectives (pp. 339–359). London: Routledge.

Davies, W. (2003). You don't know me, but... Social capital and social software. London: Work Foundation.

Downes, S. (2007, June). An introduction to connective knowledge. Paper presented at the International Conference on Media, knowledge & education—exploring new spaces, relations and dynamics in digital media ecologies. Retrieved from http://www.downes.ca/post/33034.

Downes, S. (2008). Places to go: Connectivism & connective knowledge. Innovate, 5(1). Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info/pdf/vol5_issue1/Places_to_Go-__Connectivism_&_Connective_Knowledge.pdf.

Dron, J. (2006). The way of the termite: A theoretically grounded approach to the design of e-learning environments. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 2(1), 3–16.

Dron, J., & Anderson, T. (2007). Collectives, networks and groups in social software for e-learning. Paper presented at the Proceedings of World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education, Quebec. Retrieved from www.editlib.org/index.cfm/files/paper_26726.pdf.

Dron, J., & Anderson, T. (2009). How the crowd can teach. In S. Hatzipanagos & S. Warburton (Eds.), Handbook of research on social software and developing community ontologies (pp. 1–17). Hershey, PA: IGI Global Information Science. Retrieved from www.igi-global.com/downloads/excerpts/33011.pdf.

Dron, J., & Anderson, T. (2009). Lost in social space: Information retrieval issues in Web 1.5. Journal of Digital Information, 10(2).

Fields, R. D. (2005). Making memories stick. Scientific American, 292(2), 75–81.

Gagne, R. M. (1965). The conditions of learning. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Galley, R., Conole, G., Dalziel, J., & Ghiglione, E. (2010). Cloudworks as a ‘pedagogical wrapper’ for LAMS sequences: Supporting the sharing of ideas across professional boundaries and facilitating collaborative design, evaluation and critical reflection. Paper presented at the 2010 European LAMS & Learning Design Conference, Oxford.

Garrison, D. R. (1985). Three generations of technological innovations in distance education. Distance Education, 6(2), 235–241.

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Computer conferencing: The post-industrial age of distance education. Open Learning, 12(2), 3–11.

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Implications of online and blended learning for the conceptual development and practice of distance education. The Journal of Distance Education, 23(2). Retrieved from http://www.jofde.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/471/889.

Garrison, D. R., Archer, W., & Anderson, T. (2003). A theory of critical inquiry in online distance education. In M. Moore & G. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of distance education (pp. 113–127). New York, NY: Erlbaum.

Garrison, R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical thinking in text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2), 87–105.

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. (2009). Learning, teaching, and scholarship in a digital age: Web 2.0 and classroom research: What path should we take now? Educational Researcher, 38, 246–259.

Hall, R. (2008). Can higher education enable its learners' digital autonomy? Paper presented at the LICK 2008 Symposium.

Hendler, J. (2009). Web 3.0 emerging. Computer, 42(1), 111–113. Retrieved from http://www.ostixe.com/memoria/files/publicaciones/Junio/web3.0emerging.pdf.

Holmberg, B. (1989). Theory and practice of distance education. London, UK: Routledge.

Honebein, P. C. (1996). Seven goals for the design of constructivist learning environments. In B. Wilson (Ed.), Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design (pp. 11–24). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

Ireland, T. (2007). Situating connectivism. Retrieved from http://design.test.olt.ubc.ca/Situating_Connectivism.

Jonassen, D. (1991). Evaluating constructivistic learning. Educational Technology, 31(10), 28–33.

Kanuka, H., & Anderson, T. (1999). Using constructivism in technology-mediated learning: Constructing order out of the chaos in the literature. Radical Pedagogy, 2(1). Retrieved from http://radicalpedagogy.icaap.org/content/issue1_2/02kanuka1_2.html.

Keller, F. S., & Sherman, J. (1974). PSI: The Keller plan handbook. Menlo Park: W. A. Benjamin.

Kop, R., & Hill, A. (2008). Connectivism: Learning theory of the future or vestige of the past? International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(3).

Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Mackness, J., Mak, S. F. J., & Wiliams, R. (2010). The ideals and reality of participating in a MOOC. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Networked Learning.

Mayer, R. (2001). Multi-media learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKerlich, R., & Anderson, T. (2007). Community of inquiry and learning in immersive environments 11(4). Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 11(4). Retrieved from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/jaln/v11n4/index.asp.

McLoughlin, C., & Lee, M. J. W. (2008). The three p’s of pedagogy for the networked society: Personalization, participation, and productivity. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20(1), 10–27. Retrieved from http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE395.pdf.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Toronto: McGraw-Hill.

Miller, G. (2003). The cognitive revolution: A historical perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 141–144.

Moore, M. (1989). Three types of interaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 1–6.

Nipper, S. (1989). Third generation distance learning and computer conferencing. In R. Mason & A. Kaye (Eds.), Mindweave: Communication, computers and distance education (pp. 63–73). Oxford, UK: Permagon.

Phillips, S. (2002). Social capital, local networks and community development. In C. Rakodi & T. Lloyd-Jones (Eds.), Urban livelihoods: A people-centred approach to reducing poverty. London: Earthscan.

Piaget, J. (1970). Structuralism. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Segaran, T. (2007). Programming collective intelligence. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly.

Siemens, G. (2005a). A learning theory for the digital age. Instructional Technology and Distance Education, 2(1), 3–10. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm.

Siemens, G. (2005b). Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. ElearnSpace. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/networks.htm.

Siemens, G. (2007). Connectivism: Creating a learning ecology in distributed environments. In T. Hug (Ed.), Didactics of microlearning: Concepts, discourses and examples. Munster, Germany: Waxmann Verlag.

Surowiecki, J. (2005). Independent individuals and wise crowds. IT Conversations, 468.

Taylor, J. (2002). Automating e-learning: The higher education revolution. Keynote address presented at the 32nd Annual Conference of the German Informatics Society, Dortmund, Germany, 1 October.

Vaill, P. (1996). Learning as a way of being: Strategies for survival in a world of permanent white water. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Warnick, B. (2008). Imitation and education: A philosophical inquiry into learning by example. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Wegerif, R. (2007). Dialogic education and technology. New York, NY: Springer.