Nancy Steel

Alberta-North Project, Canada

Patrick J. Fahy

Athabasca University, Canada

For several years, the government of the western Canadian province of Alberta has drafted policies and conducted research on the problem of populations under-represented in adult education. This Alberta-North and Athabasca University study, funded by the Alberta government’s Innovation Fund, uses the advice and educational experiences of northern former and present students, and of other community members, to identify ways of better attracting, preparing, and retaining under-represented populations in northern Alberta communities through provision and training in the use of distance delivery methods.

The research reported here commences with a review of the literature to investigate the following: 1) the contribution distance education makes globally to learning access in remote areas (and resulting economic growth for under-served populations); 2) how support is provided to retain isolated students; and 3) the help needed to assist remote students to complete distance programs. Community consultations with social service and education agencies in three communities were conducted in order to obtain their perspectives about what helps to attract and support students to educational programs and the barriers students typically encounter, which might be mitigated by distance methods. Finally, a survey was designed and distributed in 87 Alberta-North communities in northern Alberta and across Canada’s Northwest Territories to add perspective to the consultation results.

Keywords: Distance education; e-learning; pedagogy; northern; remote areas; isolated students

Alberta-North is a collaboration, unique in Alberta, among seven postsecondary education institutions: Athabasca University (AU), Aurora College, Grande Prairie Regional College, Keyano College, Norquest College, Northern Lakes College, and Portage College. The Alberta-North partnership was established in 1994 with the goal of increasing access to postsecondary programming, particularly for under-represented populations, by providing rural and remote communities with access to online distance education courses. The Alberta-North region covers 60% of Alberta’s geographic area, 9% of the province’s total population, and 51% of Alberta’s Aboriginal population.

Each institution offers online courses, from adult upgrading to career programs, and provides access through Alberta-North’s 87 Community Access Point (CAP) sites located across northern Alberta and the Northwest Territories. Each CAP site contains distance education technology and an onsite coordinator to provide course information and learning support. In 2008–2009, Alberta-North, and its affiliates (eCampus Alberta, Canadian Virtual University, and University of Calgary), offered 4,077 courses, ranging from upgrading courses to university studies.

Alberta-North’s partnership with Athabasca University was designed to address an under-researched area, namely community members’ and students’ views regarding the attraction, preparation, and retention of learners in remote northern communities. Some information exists already: in 2008, an Alberta-North study, funded by eCampus Alberta, examined the views of Alberta-North CAP site coordinators about “best practices.” The resulting report (Letkeman-McQuilikin & Neaves, 2009) offers suggestions for communicating course and program content to potential and current students, for conducting CAP site facility operations, and for general student retention and achievement, but leaves other questions about programming in the North unaddressed.

This project, funded by Alberta Advanced Education and Technology’s (AE&T) Innovation Fund, concerns ways of attracting, preparing, and retaining adult learners in Alberta’s rural and remote northern communities, based on what potential and actual students say they want and need to achieve success. It draws on, but goes beyond, previous inquiries and, as shown in the following, is based upon a history of public and educational reports and policy on education for under-represented populations, including historical and academic sources (Maslow, 1962), in both traditional and innovative delivery models (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005).

In 2003, AE&T’s First Nation, Metis, and Inuit Policy Framework: A Progress Report provided a vision and a policy statement, and articulated five goals: the availability of learning opportunities for Aboriginals, proper preparation of students for postsecondary studies, excellence in learner achievement, effective working relationships among all stakeholders, and a highly responsive education ministry. Strategies and performance measures for each goal were described in the statement.

In 2006, A Learning Alberta set out recommendations for making Alberta a knowledge-based province. The rationale for the paper was the confluence of economics and education/training, apparent in the notable fact that

while Alberta has the highest workforce participation rate in Canada, it also has among the lowest participation rate in post-secondary studies. Participation is even lower for those living in northern and remote communities, young males, First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples, persons with disabilities, Albertans with low income and education levels, and immigrants. (p. 1)

Several of the recommendations related to the paper’s goals are significant for this project, especially those addressing the educational and social needs of under-represented learners.

More recently, the Alberta government released the Roles and Mandates Policy Framework for Alberta’s Publically Funded Advanced Education System (2007) on the relation of education to economic and social prosperity. The document proposes an increase in Aboriginal enrolment, including through use of technology in remote areas. (The present project’s focus on ways to attract, prepare, and retain under-represented populations is aligned with these government policies, a factor which the authors believe contributed to its funding).

Nationally, Aboriginal groups have regularly cited access and support as participation issues in postsecondary education. In November 2005, Canada produced a series of agreements (not always acted upon) for improvements to Aboriginal well-being in Canada, including changes to access and support to education (the Kelowna Accord). In 2009, the Council of Ministers of Education (CMEC) Summit on Aboriginal Education, held in Saskatoon, discussed “priorities for moving forward on eliminating the gaps between the educational achievement of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students in Canada” (CMEC, 2010, p. 7). Themes and priorities for future emphasis included Aboriginal language and culture, equity in funding, seamlessness in provision of services, and the problems of access, retention, and graduation/completion.

The First Nations Adult and Higher Education Consortium (FNAHEC, see http://fnahec.org/Missions.htm) has developed a First Nation vision statement containing, among others, these goals:

To promote control of First Nations standards of excellence in education through support of our own accreditation processes and mechanisms. To build and maintain partnerships in the development and monitoring of appropriate legislation, policies, and regulations for First Nations adult and post-secondary educational programs and institutions. To develop and provide a range of programs and services that respond to the ongoing and changing needs of FNAHEC members. To develop and pursue economic resources that will lead to long-term financial self-reliance of FNAHEC and its members.

Alberta and Statistics Canada postsecondary statistics describe the magnitude of the problems involved in achieving goals such as those above. For example, AE&T institutional enrolment data show that Aboriginal enrolments (2008–2009) at Alberta-North partner institutions (in Alberta) collectively averaged about 20% (AE&T, 2010), suggesting that Aboriginal learners are under-represented in these institutions. (However, the data also show that the past-three-year trend has been toward a small but gradual increase in enrolment each year.)

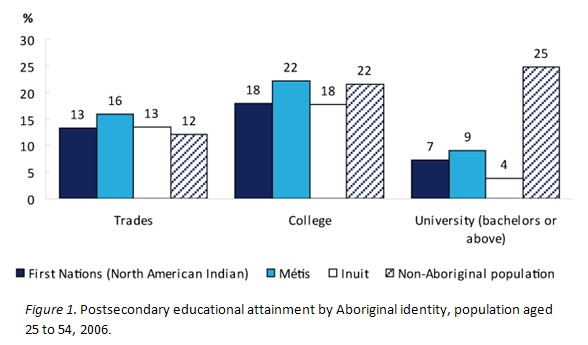

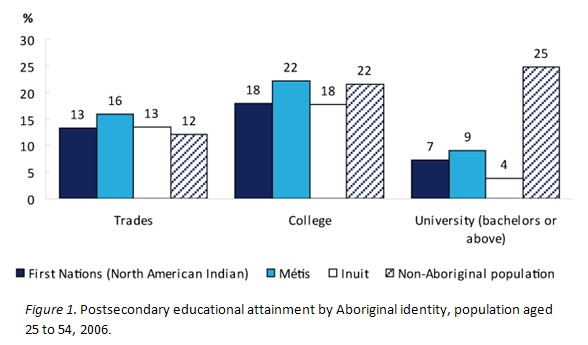

Statistics Canada census data also describes a national gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal postsecondary participation rates. As Figure 1 reveals, while there is a gap between participation rates at the university level, Aboriginals were almost as likely as non-Aboriginals to have a trades certificate or college diploma. In 2006, one-third (33%) of Aboriginal adults aged 25 to 54 had less than a high school education compared to about 13% of the non-Aboriginal population (Statistics Canada, 2010a, 2010b).

Provincial and federal statistics such as the above have shaped government policies and discussion papers, clarifying the present inequities in postsecondary systems. This research project attempts to find principles to bridge the gap between research awareness and practice by providing information from learners directly useful to programmers.

Albertan and Canadian perspectives are the focus of this review. The results describe how other jurisdictions justified inclusion of marginal populations in education and training, often through greater use of technologies. The review included 1) the contribution distance education makes to learning access (and resulting economic growth for remote or under-served populations) in Canada; 2) how support is provided to retain students; and 3) the help needed and provided to assist remotely located students to complete distance education programs. The themes mentioned are the experience of remote learners with distance education (DE); the role of family; funding assistance systems; the return on investment (ROI) from Aboriginal education; and Aboriginal culture, values, and attitudes toward learning.

Rural and remote learners, whether in traditional or distance programs, often have special needs. Bennett (2003) says of rural learners, with direct implications for distance education, “Rural communities lack a strong learning culture and rural residents may lack the literacy skills required to function in such a self-directed educational environment” (p. 5). She argues that rural residents face “a learning environment with higher attrition rates than occurs in more classroom-based offerings” (p. 6). In her opinion, and tellingly, DE approaches have in the past often been derived from the “perspective of the institution and its traditional, residential student paradigm” (p. 6) and not from “the unique community situations” of rural learners. Boud and Tennant (2006) raise a similar criticism in relation to graduate programming in Australia.

McMullen and Rorbach (2003) see special, but unfulfilled, capabilities in distance delivery: “Distance education has the ability to provide education opportunities to students in remote Aboriginal communities. To date, distance education has failed to meet this ability. Why?” (p. 6). They assert that “We have been continually told that our students have failed distance education courses. We contend that in many cases distance education courses have consistently failed the student” (p. 6). Through a series of case studies, they identified common barriers to DE for experienced learners in rural and remote communities and suggested better practices for resolving them. These and similar studies provide important perspective to our project as most northern students reside in remote communities, far from resources and assistance.

The central role of family as a support mechanism for all postsecondary students, prominent in the literature, emerged as a theme from our project survey findings. Bryan and Simmons (2009) investigated the impact of the family role on postsecondary educational success for first-generation Appalachian students. The Appalachian region resembles Alberta-North’s northern communities in that both are rural and remote, there is a level of poverty that exceeds the national average and affects postsecondary participation, and there is a strong association to community that makes leaving the community a challenge.

Taking a case study approach to conducting research with first generation postsecondary students, the authors reached several conclusions: students, often the first in the family to attempt higher education, frequently feel daunting pressure to succeed, potentially affecting their academic performance; poverty can be another form of pressure because “You know if you fail, your family is not going to be able to bail you out of it or help you . . . and you know that you’re different than middle class sort of families” (Bryan & Simmons, p. 401); and students may become isolated from family members, who lack direct familiarity with the student’s postsecondary experience.

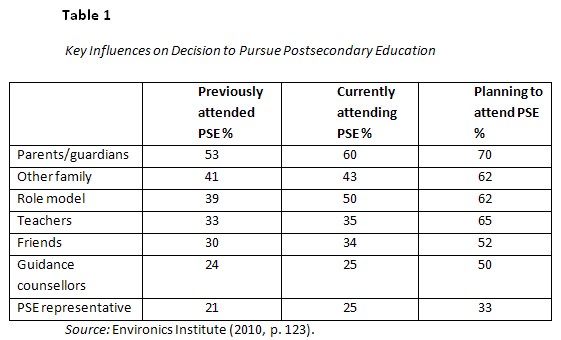

The Environics Institute (2010), in its study of urban Aboriginal people in Canada, also notes the central role that family plays in helping learners engage and succeed in postsecondary education. The study included students who have previously attended, those currently engaged, and those planning to attend postsecondary education. When asked about key influences on the decision to enrol in postsecondary education, a resounding response was “family,” although others were also mentioned, as shown below.

In the above study, “family,” “teachers/counsellors,” and “friends” were cited most often as significant supporting factors.

Another important theme that was found in the review of the literature, confirmed in our survey, is the difficulties associated with funding for Aboriginal education. Stonechild (2006) recorded the history of the Indian struggle for access to funding for postsecondary education in Canada, and the difference between the Aboriginal and the federal government interpretation of treaty rights regarding postsecondary education funding. In 1977, the federal government created the Post Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP), which provides funds for postsecondary education (upgrading education is exempt) administered and distributed by band councils. Helin and Snow (2010), among others, criticize this system as ineffective.

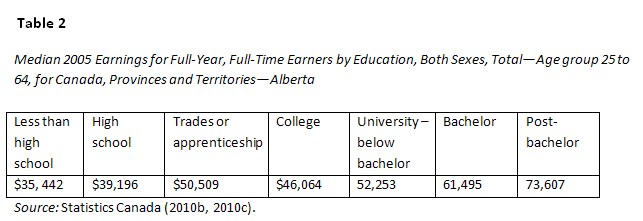

Whatever the difficulties and criticisms of the current funding system, the literature indicates that investment in Aboriginal postsecondary education in developed countries is economically justified. The relationship between earnings and education level in Canada can be seen in Table 2.

Canadian and Albertan demographic trends are similar to each other and to international patterns: the Aboriginal population is growing nearly six times faster than the non-Aboriginal population, and the Aboriginal population is significantly younger than the non-Aboriginal population (median age for Aboriginals is 27, 25 in Alberta, compared to 36 for non-Aboriginals) (Alberta Finance and Enterprise, 2008). Given Alberta’s aging population and predicted skills shortages, Alberta Employment and Immigration (2009) concludes that the Aboriginal population represents an untapped labour force, and increasing Aboriginal access to higher education may be seen as an investment in the province’s future and economy. Sharpe and Arsenault’s (2009) study draws this blunt conclusion:

Given that educational attainment is one of the key drivers of participation and employment rates, there are clear incentives for the Canadian government to make Aboriginal education a priority. If in fact Aboriginal education is not made a priority, the drag on Canadian productivity caused by below-average Aboriginal education will grow as the Aboriginal population’s share of Canada’s labour force increases over time. (p. 17)

Citing a Canadian Council on Learning report from 2007, Malatest (2008) points out that there are other benefits besides economic ones to higher education. Postsecondary education is also associated with better health and well being, and higher levels of civic and community engagement (Brown, 2009). While not a new insight, this point broadens the discussion beyond the purely economic.

A final theme that emerged from the literature review was the issue of Aboriginal culture, values, and attitudes toward learning. McMullen and Rohrbach (2003) point out that the oral tradition has historically been the main learning teaching/learning method, along with the modeling tradition, the “watch then do” approach to skill development. The authors suggest that learning tasks best suited to Aboriginal traditions involve those that are global versus analytic; those that involve images, symbols, and diagrams, rather than standalone verbal; those that are more concrete than abstract; and those that involve reflection. These traditional Aboriginal learning values have clear implications for learning designers.

The focus of the study was the question, given the lack of opportunities for non-urban people in the present postsecondary education system, and the importance of training opportunities for this group, of what actions or resources might better attract, prepare, and retain northern residents in postsecondary education programs, specifically those delivered by distance education.

Community consultations, interviews, and a written survey questionnaire were used in a variety of venues to gather input from students and others in northern communities. In the spring of 2009, the project manager visited three Alberta communities, Fort McKay, Frog Lake, and Grande Cache, to consult with community agency representatives about their services and experiences with potential or current postsecondary students. Taking an appreciative inquiry approach, which “involves the art and practice of asking questions that strengthen a system’s capacity to apprehend, anticipate and heighten positive potential” (Cooperider & Whitney, 2005, p. 3), the project manager asked questions about which approaches or strategies, in the opinion of the participants, would attract students to adult education, prepare them for program success (especially using distance technologies), and help them persist in their programs.

Also in the spring of 2009, the project team developed a survey for past, current, and potential students in Alberta-North communities. The survey was first field-tested with residents of the Peavine Métis Settlement, Alberta, and then, after revisions, was sent to all CAP coordinators, who were asked to copy, distribute, and collect completed surveys. Having CAP coordinators involved was advantageous because they are recognized education representatives in their region and have regular contact with their communities. Data analysis (by the authors) incorporated SPSS and ATLAS.ti software. In all, 482 surveys were returned from 45 communities, providing good regional scope in the data.

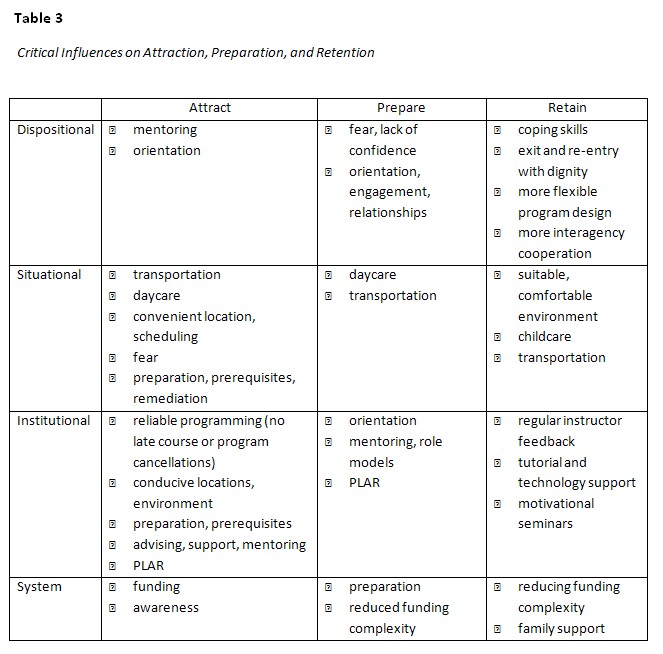

Because the focus was on how programming might be made more appealing and effective for northern residents, the consultation was based on a discussion of needs, not necessarily delivery models (distance education was not mentioned as a specific delivery strategy, though questions about it were answered wherever they arose since community members knew the study included alternative delivery models). Findings are presented below using Cross’s (1981) description of the dispositional, situational, and institutional influences that affect student participation in postsecondary (adult) education. For the purpose of the research, a fourth factor was added, the systemic factors that affect participation. Table 3 shows the main results of the interviews; implications for distance delivery are discussed in the next section.

The findings in Table 3 lead to the following general conclusions about attracting students to education and training programs:

These are the conclusions about preparation contained in Table 3:

Table 3 suggests these conclusions about retention of adult learners in northern locations:

Regarding systemic needs, Table 3 suggests the following:

The survey distributed by the CAP coordinators gathered respondent demographic data and then posed these questions, designed to supplement the community consultation results discussed above:

The survey also invited respondents to provide contact information voluntarily for possible interview follow-up.

Some of those who completed surveys did not provide information for every question. Survey participants were primarily female (58%), with a high percentage (45%) 35+ years of age. That nearly half of the respondents were 35 years of age and older is not surprising. A Canadian Council on Learning report (2009) notes that

a larger proportion of Aboriginal people return to complete their high-school education at a later age than is found in the non-Aboriginal population. This means that for a large share of Aboriginal young adults, high-school participation occurs in early adulthood rather than through the teen years, and PSE readiness can occur at a later age. (p. 44)

Of the survey participants who provided information, the majority (69%) self-identified as Aboriginal, and 29% indicated that they were First Nations, living on reserve. When asked about the highest level of education attained, nearly half (40%) indicated that they had completed some high school education, and 35% said they had some form of postsecondary education. The sample may not be representative of northern residents; it is, however, representative of the views of those northerners who have had PSE experience and who agreed to share their opinions and experiences.

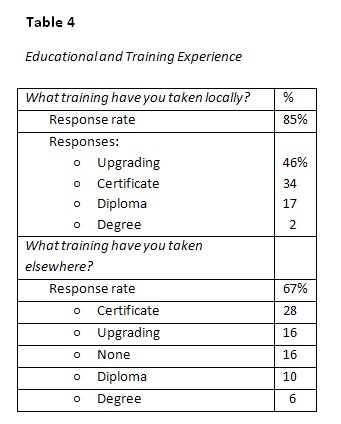

Table 4 shows the results of two questions designed to determine the education backgrounds of respondents.

Why did you leave the program?

Top responses:

Other reasons:

The above question squarely addresses reasons why students do not persist and helps to define what “personal reasons” might actually mean. Malatest & Associates (2002, p. 20) cite Donald Unruh, speaking of students at the University of Manitoba:

By far the most difficult area, and the area in which, despite our best efforts, we continue to face the greatest problems, is the area of personal and family supports. More students drop out of the programs for ‘personal reasons’ than all other reasons combined. (In fact, academic failure comes last as a reason for leaving.) . . . Family stress, discrimination, loneliness, and an alien environment combine to overwhelm students.

Our survey findings agree, and, in the above and in the following, further define what “personal” means in the context of persistence. (More is said about this point in the next section of the paper.)

What helped prepare you for your education in the community?

Sixty-seven percent of survey participants responded to this question. Top responses:

The influence of family on an individual’s decision to enrol is made clear in the literature and here in our survey’s finding. The nuances of that role merit exploration to discover ways that it can be supported and strengthened.

What hindered you, or what barriers did you have to overcome?

Eighty-nine percent of survey participants responded to this question. Top responses:

Of those who responded, a small percentage (n = 10) indicated that the question did not apply or that nothing hindered them—that they did not face any barriers.

The “fear factor” is reported regularly in the literature. Fear usually includes lack of self-confidence, trepidation at the prospect of failure, reluctance to embark on a new path (particularly if the student is a first-generation postsecondary or adult student), and reluctance to change. More research about fear is warranted in order to define it better and to explore solutions for those who experience it as a barrier to participation.

What suggestions do you have to make local training and education easier or more successful for those who take it?

Sixty-six percent of survey participants responded to this question. Top responses:

As noted in the literature review, the paucity of funding, coupled with the difficult application process and requirements, makes this an ongoing barrier to participation in postsecondary education. Our survey respondents ranked funding as the top barrier and placed it second in suggestions for improvements.

Have you heard of Alberta-North? If so, what do you know about it?

Thirty-three percent of survey participants responded to this question. It can be assumed, in this case, that a non-response might mean a “no” answer, that respondents did not know about Alberta-North. Of those who responded, 48% answered “yes.”

To the question about what they know about Alberta-North, respondents provided a variety of related responses: Distance, online, education, Web, technology or computer. Some described how they heard about Alberta-North: through affiliation with a postsecondary institution, through word-of-mouth, and through print advertising (posters, pamphlets, newsletters).

The survey activity itself served a number of purposes. Apart from its main purpose, to solicit past, current, and potential students’ ideas about their postsecondary education experience and suggestions for improvements, it also served to engage CAP coordinators in the research project and to raise the Alberta-North profile in regional communities.

The survey findings echo some of the themes found in the literature and the community consultation results, particularly the significant role that family plays as a support to students, and funding availability and access challenges.

The study established the following facts about the present provision of adult and postsecondary programs in remote northern Alberta. This analysis also reveals the potential of distance delivery to address many of the barriers students face, as shown in the comments in italics below each point:

Distance education, as it is not face-to-face (or not wholly), either does not precipitate, and may ameliorate, the impact of many of the logistical problems identified by the respondents: daycare, family and employment commitments, transportation, costs of participation, conflicts with location and scheduling, etc.

Less of an issue with distance education as more choice is in the hands of the student.

Less of an issue with distance education as either not needed at all, or other resources may become available when fixed schedules and locations for study are not imposed.

Families become more important in a distance model: families can assist with childcare, transportation, and other family management issues. Families can also use the technologies of distance to communicate with one another.

A role for Alberta-North might become the link to available distance programs and to resources that support success of learners in their use. Further study is needed to determine the extent of this problem and potential solutions.

More programs may potentially be available at a distance than can reasonably be expected in face-to-face or synchronous delivery modes.

Distance mentoring and role-modeling are potential future studies, as discussed below.

The above indicates how distance delivery might complement existing face-to-face models to address the major barriers to participation in formal learning in northern Alberta. The distinction between remote and isolated become critical (On the Frontier, 2007): Students may be the former, but, with intelligent use of technology, they need not experience the latter. Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, and Zvacek (2009) nicely summarize the distance delivery model of the future with obvious application to remote communities:

Interactive instruction is possible because telecommunications technologies permit the learner to contact databases, information sources, instructional experts, and other students in real-time and interactive ways. . . . Instruction is authentic because it is not teacher centred; rather it is content and learner centred. (pp. 22–23)

On the basis of the above analysis of distance education’s potentials, the project Advisory Committee is investigating, through two projects, how new supports might reduce barriers to learning participation for adults in remote communities. One project will see the development of a handbook of suggestions for CAP Coordinators, for instructors, and for college administrations to better attract, prepare, and retain Aboriginal students. The second project will investigate the interest of a select number of CAP coordinators in expanding their role as service providers to that of mentors. If there is an interest, mentor training will be developed and delivered, a mentorship program awareness strategy developed, and mentor-mentee activities documented. The goal of such a program is to provide students with additional support, and it is to be piloted between January 2011 and June 2011. Further reports will follow as these projects produce results.

Alberta Advanced Education & Technology. (2002). Campus Alberta: A policy framework. Retrieved from http://aet.alberta.ca/media/134142/campusalbertframework.pdf

Alberta Advanced Education & Technology. (2003). First Nations, Metis, and Inuit education policy framework: A progress report. Retrieved from http://www.education.gov.ab.ca/FNMI/fnmiPolicy//pdfs/FNMIProgRep.pdf

Alberta Advanced Education & Technology. (2006). A learning Alberta. Retrieved from http://aet.alberta.ca/media/133863/steering_committee_final_report.pdf

Alberta Advanced Education & Technology. (2007). Roles and mandates policy framework for Alberta’s publically funded advanced education system. Retrieved from http://aet.alberta.ca/media/133783/roles%20and%20mandates%20policy%20framework%20final.pdf

Alberta Advanced Education & Technology. (2010). Campus Alberta planning framework: Profiling Alberta’s advanced education system. Retrieved from http://aet.alberta.ca/capf

Alberta Employment and Immigration. (2009) Alberta’s aging labour force and skills shortages. Retrieved from http://employment.alberta.ca/documents/LMI/LMI-SSA_aging-and-shortages.pdf

Alberta Finance and Enterprise. (2008). 2006 Census of Canada, Aboriginal release. Retrieved from http://www.finance.alberta.ca/search/query.aspx?sitesearch=www.finance.alberta.ca&requiredfields=&partialfields=&q=aboriginal&btnG

Bennett, G. (2003). Strangers in a strange land: Rural learners in distance education (Unpublished master’s thesis). St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS.

Boud, D., & Tennant, M. (2006). Putting doctoral education to work: Challenges to academic practice. Higher Education Research and Development, 25(3), 293–306.

Brown, T. (2009). Supporting the engagement, learning, and success of at-risk students, Part I. Innovative Educators Webinar Series. Retrieved from http://www.innovativeeducators.org/v/vspfiles/V4_Backup/atrisk1.ppt

Bryan, E., & Simmons, L.-A. (2009). Family involvement: Impact on post-secondary educational success for first-generation Appalachian college students. Retrieved from http://0-proquest.umi.com.aupac.lib.athabascau.ca/pqdweb?RQT=572&TS=1265063697&clientId=12302&VType=PQD&VName=PQD&VInst=PROD&PMID=22023&PCID=47679051&SrtM=0&SrchMode=3&aid=2

Canadian Council on Learning. (2009). Post-secondary education in Canada: Meeting our needs? Retrieved from http://www.ccl-cca.ca/pdfs/PSE/2009/PSE2008_English.pdf

Cooperider, D., & Whitney, D. (2005). A positive revolution in change: Appreciative inquiry. Retrieved from http://appreciativeinquiry.case.edu/uploads/whatisai.pdf

Council of Ministers of Education Canada. (2010). Strengthening Aboriginal Success: CMEC summit on Aboriginal Education. Retrieved from http://www.cmec.ca/Pages/Default.aspx

Cross, P. (1981). Adults as learners. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Environics Institute. (2010). Urban Aboriginal peoples study. In Educational values, aspirations and experiences (pp. 117–128). Retrieved from http://www.uaps.ca/

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. American Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133–148.

Helin, C., & Snow, D. (2010). Free to learn: Giving Aboriginal youth control over their post-secondary education. Retrieved from http://www.macdonaldlaurier.ca/home/

Letkeman-McQuilikin, J., & Neaves, V. (2009). Successful practices for distance learners. Available by request from Alberta-North email alberta-north@northernlakescollege.ca

Malatest & Associates. (2002). Best practices in increasing Aboriginal postsecondary rates. Retrieved from http://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/49/malatest.en.pdf

Malatest, R. A. (2008). Factors affecting the use of student financial assistance programs by Aboriginal youth: Literature review. Retrieved from http://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/197/factors-affecting-aboriginal-youth.pdf

Maslow, A. (1962). Toward a psychology of being. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.

McMullen, B., & Rohrbach, A. (2003). Distance education in remote aboriginal communities. Retrieved from http://www.cnc.bc.ca/__shared/assets/Distance_Education_in_Remote_Aboriginal_Communities7675.pdf

On the frontier. (2007, November 17). The Economist, 385(8555), 40.

Sharpe, A., & Arsenault, J.-F. (2009). Investing in Aboriginal education in Canada: An economic perspective. Retrieved from http://www.cprn.org/theme.cfm?theme=62&l=en

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek, S. (2009). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Statistics Canada. (2010a). Aboriginal statistics at a glance. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-645-X. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-645-x/2010001/education-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2010b). Postsecondary educational attainment by Aboriginal identity, population aged 25 to 54, 2006. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-645-X. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-645-x/2010001/c-g/c-g009-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2010c). Median 2005 earnings for full-year, full-time earners by education, both sexes, total – age group 25 to 64, for Canada, provinces and territories. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/earnings/Table803.cfm?GH=4&Lang=E&O=A&SC=1&SO=99&T=803

Stonechild, B. (2006). The new buffalo: The struggle for Aboriginal post-secondary education in Canada. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.