Shifting from an emphasis on teaching to learning is a complex task for both teachers and students. This paper reports on a qualitative study of teachers in a nurse specialist education programme meeting this shift in a distance education course. The study aimed to gain a better understanding of the teacher-student relationship by addressing research questions in relation to the students’ role, the learning process, and the assessment process. A didactical design comprising three phases focusing on distinct learning outcomes for the course was adopted. Data were collected through in-depth interviews with teachers and were analysed using inductive thematic analysis. The results indicate a shift towards a problematising and holistic approach to teaching, learning, and assessment. This shift highlighted a teacher-student relationship with a shared responsibility in the orchestration of the learning experience. The overall picture outlines a distance education experience of process-based assessment characterised by the imposition of teachers’ rules and a lack of creativity due to the limited role of ICT merely as a container of content.

Keywords: Distance education; higher education; e-learning

Shifting the emphasis from teaching to learning involves a complex process of changing structures in the education system (Barr & Tagg, 1995). One catalyst for changing structures is the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in education and society (Brown, 2006). In Sweden, ICT was introduced to the policy agenda in 1994, following the political initiative from the USA in 1993 (Karlsson, 1996). The introduction of ICT was also a starting point for the increased use of ICT in education and particularly in distance education. Previous studies in nurse distance education have investigated the impact of constructivist approaches to teaching and learning (Legg, Adelman, Mueller, & Levitt, 2009) as a theoretical framework for designing educational experiences (Peters, 2000; Twomey, 2004). In practice, constructivist learning is characterised as active and responsive to individual needs of the learner (Dalgarno, 2001). However, in constructivist studies, the teacher-student relationship is implicit through the interpretation of, for example, being an active learner. Few studies have focused on the teacher-student relationship as such in distance education that involves a shifting emphasis from teaching to learning.

Bergström and Granberg (2007) argue that the use of process diaries is one response to the need to bridge the distance in relation to teaching, learning, and assessment in distance education courses. Process diaries are used to support student reflection that is supported by feedback for monitoring and guidance from teachers at regular intervals. Moreover, process diaries illuminate the conflict for the tutors between their roles that on the one hand are to support formative assessment and on the other to make judgements in relation to summative assessment. Hudson et al. (2009) regard process-based assessment as a formative process that focuses on students’ learning over a period of time instead of simply on the product of learning. As a result of this move towards approaches that involve formative assessment and the regular use of feedback, the preconditions of the learning process in distance education are changing. These changing preconditions are considered in terms of Bernstein’s (2000) conceptual framework as a relationship between an instructional discourse and a regulative discourse. The concept of discourse is perceived as the teachers’ or the students’ style of talking and understanding of their practice (Winther Jørgensen, 2000). The instructional discourse creates what Bernstein refers to as specialised skills (Bernstein, 2000, p. 32). From an interview study with in-service nurse students, Bergström (2010) reported on the diversity of skills when students start to focus on the learning process through process-based assessment. The diversity of skills was illuminated through the students’ shift of thinking from desk teaching to self-regulated learning, from reproductive learning to productive learning, and from norm-referenced marks to self-reflective assessment. However, the regulative discourse is regarded as teachers’ rules of order, in other words what is tolerable or not in the teacher-student relationship. The regulative discourse is the dominant discourse in relation to the instructional discourse.

In this study, the focus is turned onto the teachers’ perspective as representative of the teacher-student relationship. Therefore, the aim was to understand the teacher-student relationship in the regulative discourse contextualised within a changing emphasis from teaching to learning in distance education. Thus, the following research questions were addressed in relation to the expectations of and beliefs about teaching, learning, and assessment from the teachers’ perspective:

At the time of this study in 2007, the teachers involved had experienced two significant turning points during a five-year period. The first turning point was the increased use of ICT that became a catalyst for distance education, and the second was the Bologna reform of higher education.

The teachers in this study worked at a department for specialist nurse education in Sweden. In 2002, a strategic decision was taken at the department to move to distance education. This new approach to teaching and learning was regarded as a turning point in each of the teachers’ careers. The decision to adopt distance education as the main approach to teaching and learning resulted in the integration of ICT into distance education courses. This created a bottom-up response (Richards, 2004) in the process of shifting the emphasis from teaching to learning. This prompted change in both the learning environment and the pedagogy, which was a result of limiting the regular face-to-face course meetings and shifting towards communications through e-mail and an online approach. The online learning environment is based on a learning management system (LMS) that is used for archiving and displaying assignments and for communication between teachers and students. A web-based video conference tool was used for synchronous communication and collaboration in base groups amongst the students and the teachers. As a result, the students visited the university at the beginning and end of the semester. Through this approach, the number of face-to-face course meetings has decreased by 50%. Moreover, the increased use of ICT can be seen as an example of Richard’s (2004) notion of a changed rhetoric towards new ideas and models for developing this kind of practice and context. For these teachers, the rhetoric was characterised by increased demands for developing flexible courses every year and also for alternative approaches to assessment. Recruitment has developed from enrolling students in the neighbouring counties of the university to recruiting students from other parts of Sweden. This development has created pedagogical demands in terms of meeting student needs without having them travel to the university. However, the changed rhetoric is also part of curriculum reforms towards outcome-based models of education.

In Europe, the Bologna process is considered as the most important reform (Eurydice, 2009), which was introduced in Sweden in 2007 (Ministry of Education and Science, 2006). Accordingly, the teachers rewrote the learning outcomes in the syllabus according to the Bologna model. Changing the curriculum has been part of the change in emphasis from teaching to learning (Karseth, 2006). The key challenges for higher education are still considered to be shifting from an instructional paradigm towards a learning paradigm by addressing diversity in learning (TRENDS, 2010) and by recognising the needs for greater flexibility (TRENDS, 2005). A curriculum according to the Bologna model outlines the shift from content-based learning to outcome-based learning (Biggs & Tang, 2007). The teachers chose three learning outcomes for the process-based assessment, which were to

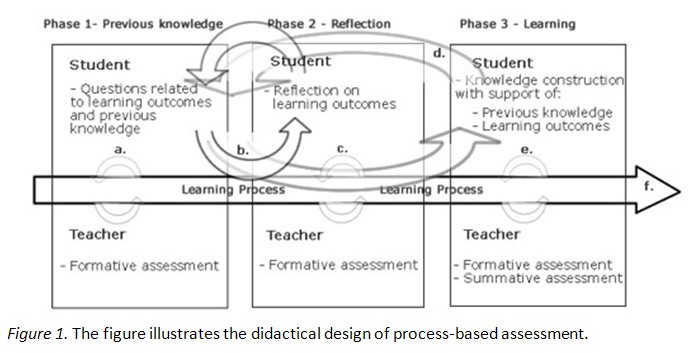

The figure below (Bergström, 2010) illustrates the didactical design of process-based assessment for a course of study. The didactical design takes its starting point from the three phases that aimed at covering and capturing the students’ learning process during the course.

Phase 1 establishes the starting point of the course. In this phase, students describe previous life, work, and study experiences upon which the teacher gives students feedback (a). In the middle of the course (phase 2), students reflect on their previous knowledge and the learning outcomes (b), which are followed by teacher feedback (c). When students come to the final phase of the course (phase 3), they summarise their learning in relation to previous knowledge and learning outcomes (d). Then the teacher provides feedback on the students’ texts and makes a final judgement (e). Students focus on the documentation of their experiences, events, and concepts and over a period of time gain insight into self-awareness and learning, which constitutes the learning process (f). Recordings of the students’ reflections and outcomes of process-based assessment were stored in document files in the LMS for the course.

The teachers used a template developed in a teacher education programme, which was a 10-page document covering all of the phases. The students started by writing about themselves, on topics such as experiences from higher education and work in relation to the theme of the course, child health and school health service. In the first phase—based on previous knowledge—the students were asked to describe their previous knowledge in relation to each learning outcome. In the second phase, the students’ task was to reflect on the learning outcomes in relation to the course assignments, the literature and the lectures. In the final phase, the teachers asked the students to analyse their learning in relation to the learning outcomes and reflections.

In order to understand the regulative discourse, the material was analysed through the lens of the message system: curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation (Bernstein, 1977, 1990). These three concepts are only used as analytical concepts. In this analysis, Bernstein’s key concepts of classification and framing were applied. In order to understand the conditions and reproduction of the teacher-student relationship, the message system was analysed from the perspective of educational codes, in other words elaborated code and restricted code (Bernstein, 1990).

Bernstein used the concept of curriculum with a theoretical and symbolic meaning similar to that of Stenhouse, cited in Ruddock and Hopkins (1985). Stenhouse explains the symbolic meaning of the curriculum as having “a physical existence but also a meaning incarnate in words or pictures or sound or games or whatever” (Ruddock & Hopkins, 1985, p. 67). Accordingly, curriculum is interpreted with a broad understanding covering the teachers’ practice. In this analysis, curriculum is analysed through the concept of classification (Bernstein, 1977, 1990), which informs us about the relationship between categories. Classification is a relative concept and is either strong or weak. However, classification can be applied to an analysis at different levels, such as the relationship between the external and the internal value of classification. For example, the external value of classification can consider an educational reform in relation to the internal value of classification, which considers elements of content in a course’s syllabus. These values inform us about the power relationship between categories. Strong classification signifies a hierarchical power relationship, while the opposite pertains to weak classification. Bernstein (1990) argues that strong classifications reproduce relationships among categories.

The concept of pedagogy highlights the pedagogical practice from a theoretical perspective, which is perceived through the relative concept of framing, creating the notion of a message (Bernstein, 1977, 1990). This message is derived from the relative nature of framing that informs us who is in control, for example in the teacher-student relationship. If the analysis has a purpose of understanding something external, for example a reform, in relation to the internal pedagogical practice, two values need to be considered. An educational reform with a value of weak external framing carries a message of teacher control. In the pedagogical practice, a study guide with low structure has a value of weak internal framing and the students are in control, such that they could have, for example, influence on the learning environment. Thus, understanding pedagogy through the concept of framing, Bernstein (1990) argues that the notion of control creates a message in the external-internal relationship.

According to Bernstein (1977), evaluation is a function of curriculum and pedagogy and is understood as the relationship between classification and framing. In practice, evaluation is understood as the teachers’ assessment. Accordingly, the assessment practice depends on the syllabus and the teachers’ approach to teaching and on how the learning environment is arranged.

Bernstein (1990) explains an educational code as something tacitly received by taking part in education. The meaning of the code (its orientation) communicates two themes: an elaborated code derived from the principle of keeping things apart or a restricted code derived from the principle of keeping things together. In this paper, the educational code is considered to be the symbolic relationship between policy and practice. The analytical tool for investigating the code concerns the relationship between the internal and external values of the relative concepts of classification and framing. For example, if a policy reform is mandatory for the institution, external classification is strong. If the message of the reform aims to tell the teachers how to teach and assess, external framing is strong. Depending on the relationship between the external and internal values, the analysis points towards a specific meaning as either an elaborated or a regulative code (Bernstein, 1990).

A qualitative approach was adopted in order to understand the regulative discourse in the shift in emphasis from teaching to learning. The regulative discourse in the teacher-student relationship was studied from the teachers’ narratives of process-based assessment. A strategy for reading and analysing the texts is outlined, which addresses the trustworthiness of the interpretations of the empirical material.

The two teachers (N = 2) who taught in the course were chosen for in-depth interviews. They are above the age of 50 and have worked with distance education for between four and five years. Because the study was conducted over one semester, the model for interviewing the teachers was through four semi-structured, in-depth, face-to-face interviews. The interviews followed the occasions for teacher-student interaction in the didactical design. Before they were interviewed, the interview themes were tested with two other teachers. This process contributed to a modification of the interview themes and the follow-up questions. For the teachers in this study, the first interviews were conducted between June and August 2007, focusing on the teachers’ background as teachers. The second interview took part three weeks after the course started in September, focusing on the work of the students’ previous experiences. In December, a third interview focused on the students’ reflections. In January and February 2008, a fourth interview took place focusing on students’ learning. The interviews followed a structure of themes according to the didactical design and areas of teaching, learning, assessment, and use of ICT. The interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed, and notes were taken during the interviews. The recorded material from the interviews amounted to 11 hours and 35 minutes.

At the outset, the teachers agreed to a statement of research ethics. This followed the guidelines from the Swedish Research Council (2001) and addressed the aspects of beneficence, non-malfeasance, informed consent, and confidentiality/anonymity.

The empirical material was analysed through inductive thematic analysis influenced by Boyatzis (1998) and Malterud’s (2009) approaches. The empirical material was read and re-read several times, ultimately interpreting what the interviewees were implicitly or explicitly saying. In this process of understanding the essence of the interviews, a strategy was followed in which important signs (Malterud, 2009), episodes, comparisons, and contrastive thinking (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996) were searched for in the written transcriptions. An analytical process of searching for a relationship in the captured essences of the empirical material then followed. As a result of this process, three descriptive themes could be coded to a majority of the empirical material. The reliability and validity of the coding was considered in the subsequent reading of the material in light of the strategy for capturing the essence. Text of the chosen learning outcomes in the syllabus with regard to meaning-bearing concepts was analysed in relation to the interviews. However, as the purpose of my research was to better understand the teacher-student relationship in process-based assessment, taking the analysis a step further was necessary. This step moved from the descriptive level to a higher analytical level by integrating theory into the analysis in order to investigate what underpinned process-based assessment. The themes were interpreted through Bernstein’s (1977) message system of curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation by using the relational concepts of classification and framing. The results from the analysis of the message system in the form of the educational code were outlined in order to understand the regulative discourse.

The results are structured and presented in two stages, with the aim of understanding the teacher-student relationship in light of the research questions regarding the student role, the learning process, and the assessment process from the teachers’ perspective. In the first stage, the teachers’ practice was analysed. In this process of analysing the empirical material, five descriptive categories were found: the organisation of the course, the confusion of working in the LMS, the teachers’ criteria for assessment, difficulties in assessing the students, and a contextualised learning process. The five categories were developed into three themes covering most of the empirical material. The three themes are the teachers’ relationship with the students, the teachers’ interaction with the content, and the students’ interaction with the content. These results were analysed through Bernstein’s (1977) message system of curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation. The teachers’ voices were frequently quoted from the interviews. Furthermore, in this study the teachers’ narratives about their feedback, actions, and ideas were important sources for understanding the themes according to the message system of curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation. The names of the teachers are replaced with pseudonyms.

In the second stage of the analysis for understanding the teacher-student relationship, the focus turned to the relationship between policy and practice. By applying Bernstein’s (1990) educational codes through a theoretical lens, the social relationship from practice could be analysed in relation to educational reforms.

In the teachers’ relationship with the students, the relative concept of classification highlighted the relationship between valid content from the learning outcomes and less valid content from the students’ process. Moreover, the relative concept of framing outlined the teachers’ mode for communication in the teacher-student relationship.

In the students’ previous knowledge, a curriculum of weak classification was expressed. In practice, the weak classification was seen when the teachers encouraged the students to use content outside of formal education, for example the students’ professions or lives. Ellen explained, “I ask . . . if they don’t think that they have learned somewhere else [in another situation].” Moreover, a shift towards strengthened classification was highlighted in the second phase of the process-based assessment by using the learning outcomes in the syllabus. Ellen reflected, “I repeated more of what they said [in Phase 1] . . . but [in Phase 2] I use the learning outcomes, which I take as a starting point.” Overall, the teachers expressed a curriculum in the process of change—from strong to weak classification with regard to the students’ content. Changing the feedback involved another approach to the students’ content in practice, which was a move from feedback of confirmation and summaries towards a problematising approach. The wish for a changed approach in practice outlines a strengthened perspective of a curriculum of weak classification. Caryn said, “I will try to think more from a reflective and problematising approach.”

The teachers’ approach in practice highlighted the difficulties of bringing the students’ skills and experiences to a predefined course structure. The teachers’ approach highlighted tacit communication with the students in the syllabus and in the instructions of the template but also explicit communication in the teachers’ feedback to the students. In the document files, the template showed a method of strong framing through signals of non-negotiation with the students in which the learning outcomes were chosen in advance. However, the format of the questions in the template indicated weak framing: the students had the freedom to write about their skills and experiences in relation to the learning outcomes. The teachers’ approach to the students was not to take a standpoint. Ellen argued, “The students have what they have as previous knowledge.”

The teachers saw their own reflections and analyses about their feedback as repetitive, the majority of their comments as too general, and their questions not sufficiently open. Ellen said, “By giving summaries of what has been said . . . and maybe an open question.” The teachers’ approach indicated weak framing because of the students’ right to create content. In the students’ reflections (phase 2), framing became stronger when the teachers used the learning outcome as a point of reference for validating the students’ element of content. Caryn explained, “Firstly, I encourage them . . . and then I give support or express if something is missing.”

The function between the strengths of classification and framing reflected a shift in assessment. The teachers argued for a move towards a problematising approach through weak classification and framing. Thus, the assessment condition did not highlight a question of right or wrong in the student-teacher relationship. Instead, the teachers’ feedback outlined encouragement by confirmation, as Caryn explained, “To confirm the students’ writing . . . they shall feel themselves confident in their creative process. I think this is very important,” and by questions in which the students self-regulate their learning. Ellen said, “I thought when the students got these questions back they should reflect a bit more without replying to me.”

In this theme of the teachers’ relationship to the content, the learning outcomes were explicitly discussed and valued in relation to process-based assessment. Classification informs us about the insulation of content in relation to the learning outcome. Framing, the issue of control in the teacher-student relationship, was derived from the teachers’ reasoning about the philosophy in the course design and for process-based assessment.

For process-based assessment, the teachers chose three learning outcomes in the syllabus that raised different expectations of learning. The three learning outcomes contained the verbs “to analyse,” “to identify,” and “to describe.” In the students’ learning, they encountered content that yielded a variety of answers reflecting the nurse practice in clinic. The teachers found that the learning outcome in the syllabus gave different categories of answers, from diverse to predefined. The three verbs highlighted to what extent the formal content had strong borders in relation to other categories of content. The two verbs “to analyse” and “to identify” in the syllabus were open to different perspectives, indicating a curriculum of weak classification. Caryn implicitly expressed the diverse nature of the verb “to identify”: “In the first learning outcome, [the students] have to think how they identify those, which is some kind of process.” The verb “to describe” outlined a curriculum of strong classification. This means that there are strong borders in relation to other categories of content, for example informal content outside the context of study. Ellen explained, “I think to describe that is at a rather low level . . . just . . . describe what you have read in a book.”

The teachers were forced to use a particular LMS that highlighted strong framing in which neither teachers nor students had enough control to change the space. A mistake in the setting with regard to the number of submissions of the document created a confusion of documents on different computers, the need for cut and paste between documents, and feedback sent through different channels of communication such as e-mail and instant messaging.

Caryn explained,

It is not possible to submit them again . . . instead they send them through PIM [instant messaging] and e-mail . . . My thought was it is a little bit of a mess! Where was that file stored?

The teachers aimed for a problematising approach in which the students had increased control over choosing content. Teachers can only estimate plausible sources of knowledge and consider how the students use a particular situation. These teachers described an approach of weak framing in the students’ interaction with the content. Ellen said, “This kind of learning outcome such as “identify children . . . Several students have been working close to [the learning outcome], and several of them had met it in other circumstances, for example in school.” Ellen continued, “When [the students] have been at the clinic at practice and meet patients, which they refer to at several occasions [in the text] . . . then the students have learned from the situation.” However, the teachers saw a conflict between the approaches of weak framing in relation to strong framing. Caryn explained, “Some students think it is more enjoyable to read a textbook with a predefined answer instead of problematising.”

In the relationship between the strengths of classification and framing, understandings of assessment diverged. A divide emerged between what the teachers expected from the students and what they believed about the students’ approach to learning. Weak classification is by definition a weak insulation between what the teachers can expect of the students’ text in relation to the learning outcome. The students can decide what is and is not valid content. This creates a situation involving various responses among the students, which Caryn had noted, finding that “the students’ answers were often diverse.” The diversity of the students’ text became part of the nature of assessment.

The practice of the teacher-student relationship was highlighted by the three components of the message system: curriculum, pedagogy, and evaluation. The concepts of the message system were derived from the relative concepts of classification and framing. Classification and framing gave rise to diverse conditions of the social relationship through the concepts of power and control. For a better understanding of the teacher-student relationship at an institutional level, Bernstein’s (1990) educational codes were used in the analysis.

In the analysis at the institutional level, the use of the theory of elaborated code and restricted code (Bernstein, 1990) highlights the conditions and (re)production of the teacher-student relationship in a Swedish context. Two significant changes at the department pointed to a particular meaning and interactional context (Bernstein, 1990). The Swedish higher education reform of 2007 made the Bologna reform mandatory for the higher education institutions, indicating strong external classification. The guidance at the policy level is intended to promote student-centred learning and flexibility (TRENDS, 2005, 2010), indicating a message of weak external framing. The teachers’ adaptation of the Bologna reform yielded a curriculum of weak classification. The interactional context in society has changed in relation to the bottom-up effect of ICT (Richards, 2004). People’s daily use of the technology and the top-down effect of the Swedish ICT policy (Karlsson, 1996) indicates strong external framing. The department followed this transition by shifting the interactional context for teaching and learning towards distance education supported by the use of ICT. Process-based assessment is an isolated part in relation to the other parts, such as seminars and assignments, in this study. This is based on a design and approach with a preponderance of weak internal framing highlighted in the message system of pedagogy.

In summary, the educational code informs us of the relationship between the decisions taken at a policy level and the teachers’ practice. This analysis outlines a framework of the regulative discourse of policy and practice. The educational code for this institution’s approach to distance education indicates a restricted code. The reforms supported Bernstein’s notion of keeping things together, which created this particular teacher-student relationship in process-based assessment.

This study aimed to create a better understanding of the teacher-student relationship in the shift from teaching to learning by studying the regulative discourse of process-based assessment. The aim was reached by addressing the three research questions, which considered the students’ role, the learning process, and the assessment process. In relation to the students’ role, process-based assessment gave them a voice, ultimately giving them power and control, particularly in the learning process. In relation to the learning process, bringing different experiences together through reflections raised issues of a changed practice that also affected the assessment process. Finally, in relation to the assessment process, a changed practice was highlighted through the relationship between curriculum and pedagogy.

The student role in the restricted code outlined a specific practice building on preponderance towards a power relation in which the students have ownership. The students were meeting a changed approach for teaching, learning, and assessment through the problematising and holistic approach. The teachers’ indication of what the students expected (an elaborated code) was in contrast to the restricted code they faced in process-based assessment. The restricted code was found in the issue of power and control. The students were expected to find relevant elements of content in relation to the learning outcomes. This approach was difficult for the students to internalise, which did not become easier due to the teachers’ inexperience with the pedagogy. Moreover, a contradiction to this approach and to the changed student role was the detailed structure of the document files showing the teachers’ tacit power. However, the student role in this distance course was complex due to both a formal and an informal curriculum and to the pedagogy because the assignments held strong framing (and probably strong classification). This will be considered in relation to the students’ responsibility for finding situations in practice and for reflecting holistically on their roles as nurse students becoming specialist practitioners.

In the learning process from the perspective of a restricted code, the teachers were pointing out the shift towards students’ texts with a problematising approach. The instructional discourse outlined the problematising and holistic approach, which also indicates the regulative discourse in practice. The regulation was tacit and diverse in the curriculum, and the change in the mode of teaching would probably need to be strengthened in the instructions to the students, which is a question of both designing the curriculum and of ways of understanding this distance education pedagogy. Clearly, in this distance education context the learning outcomes in the syllabus became an important tool in the learning process. The students faced both formal and informal learning outcomes that were also part of the complex picture. In order to take care of the learning process, there is probably a strong need for developing learning outcomes that address the process outcomes. Relevant examples of such outcomes are those derived from the voice of these teachers with regard to the verbs “to make visual” and “to make aware of.”

The teachers’ feedback was also part of the students’ learning process. For the teachers, one of the difficulties was to give relevant feedback. The encouraging and confirmative feedback was rather passive and kind in relation to the teachers’ wish for being more active through open questions. This is an issue that highlights the power relationship between the teacher and the student. When the teachers were passive, they did not use their power. The teachers used their power if the student had gaps in the learning outcomes in the syllabus. In principle, the students were open-minded in their texts according to the holistic approach of bringing different experiences of learning together. The teachers expected the students to take care of their learning process without the teacher watching. In contrast, if students expect an elaborated code and they do not know what is expected of them, there is a tacit conflict of different expectations in the student-teacher relationship.

The analysis of the results pointed to the teachers’ and students’ use and the purpose of using information and communication technologies (ICT). The use of ICT made it possible to conduct this course at a distance. Technology helped both the teachers and students to interact at a distance through the storage of document files. However, the problem is that ICT was used as nothing more than a container of content supporting interaction and storage, which the teachers cannot be blamed for. This use of ICT outlines a traditional approach to teaching and learning created by the LMS provider. As a container of content, ICT supported communication in the teacher-student relationship; however, none of the information is shared, tagged, or processed by the computer. This would probably provide a different dimension to the teacher-student relationship.

The assessment process from the perspective of the restrictive code indicated complexity with regard to the teacher-student relationship. In practice, assessment was difficult due to the detailed structure of the template because of issues related to the students’ self-esteem. This complexity highlighted the power relationship between the formal and informal learning outcomes in relation to the personal nature of the students’ texts. The student texts were regarded as a source for developing and encouraging the students in their learning. Furthermore, the teachers’ action and thinking showed a humble attitude in relation to the nature of the students’ texts with regard to ownership of their reflection and analysis.

The informal learning outcomes deserved to be expressed formally in the syllabus. This would be a significant reform at the institutional level but also a strengthening of the restrictive code. However, it is probably easy to fall into the trap of discussing summative assessment of facts in relation to process-based assessment of the students’ learning. This is not a question of decreasing the specific facts nurse specialist students need to gain in order to get certification through summative assessment. This is a question of developing the students’ previous knowledge and learning in order to make their distance learning experience richer.

In summary, this study shows an increased understanding of the teacher-student relationship from the perspective of the regulative discourse. This discourse highlights the shift in emphasis from teaching to learning through the research questions, which focused on the student role, the learning process, and the assessment process. With regard to the social relationships, this study highlights the complexity of this shift, which encompasses the three aspects identified in the research questions. However, in relation to the student role, students need to perceive their teacher more as a critical friend than an assessor. For example, in the contrast between the formal learning outcomes and the informal learning outcomes, it is plausible to believe that the student role is a response to the formal learning outcomes. The problematising approach in practice shows a richer learning process but also highlights a difficult and complex shift in the teachers’ practice. The complexity is related to the teacher-student relationship in which students’ power and control are increased by new and different expectations. The assessment process is also part of the relationship between power and control. In order to make the learning experience richer, students and teachers need to change their approach to assessment, which also relates to the student role and the learning process. The students need to assess themselves, and the teachers need to guide them through that process with learning outcomes that support diversity and build on personal experience. Finally, the role of ICT, that is the LMS, provides a problematic picture of the social processes highlighted in this paper. The internal meaning of the LMS only supported storage of content, nothing more. Accordingly, the use of this LMS reinforced the traditional roles in the teacher-student relationship.

Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, (Nov./Dec.), 13–25.

Bergström, P. (2010). Process-based assessment for professional learning in higher education: Perspectives on the student-teacher relationship. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11(2).

Bergström, P., & Granberg, C. (2007). Process diaries: Formative and summative assessment in on-line courses. In N. Buzzetto-More (Ed.), Advanced principles of effective online teaching: A handbook for educators developing e-Learning. Santa Rosa, CA: Information Science Press.

Bernstein, B. (1977). Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmissions

(Vol. 3). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bernstein, B. (1990). Class, codes and control: The structuring of pedagogic discourse (Vol. 4). London and New York: Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique (Revised ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (3rd ed.). Glasgow: Open University Press.

Boyatzis, R. (1998). Thematic analysis and code development: Transforming qualitative information. London and New Delhi: Sage.

Brown, T. H. (2006). Beyond constructivism: Navigationism in the knowledge era. On the Horizon, 14(3), 108–120.

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data. London and New Dehli: Sage.

Dalgarno, B. (2001). Interpretations of constructivism and consequences for computer assisted learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(2), 183–194.

Eurydice network. (2009). Higher education in Europe 2009: Developments in the Bologna Process.

Hudson, B., Granberg, C., Österlund, D., Bodén, A., Scherp, H-Å., Scherp, G-B., Liljeqvist, H., & Johansson, M. (2009). P@rable Project—Process based assessment through blended learning. Retrieved from http://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/21543/1/gupea_2077_21543_1.pdf.

Karlsson, M. (1996). Surfing the wave of national IT initiatives – Sweden and international policy diffusion. Information Infrastructure & Policy, 5(3), 191–205.

Karseth, B. (2006). Curriculum restructuring in higher education after the Bologna Process: A new pedagogic regime? Revista Española de Educación Comparada 2006, 12, 255–284.

Legg, T. J., Adelman, D., Mueller, D., & Levitt, C. (2009). Constructivist strategies in online distance education in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(2), 64–69.

Malterud, K. (2009). Kvalitativa metoder i medicinsk forskning (Vol. Andra upplagan). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Ministry of Education and Science. (2006). Högskolereformen 2007 (Reform of Higher Education 2007; in Swedish). Retrieved from http://www.sweden.gov.se/sb/d/5696/a/66504

Peters, M. (2000). Does constructivist epistemology have a place in nurse education? Journal of Nursing Education, 39(4), 166–172.

Richards, C. (2004). From old to new learning: Global imperatives, exemplary Asian dilemmas and ICT as a key to cultural change in education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 2(3), 337–353.

Ruddock, J., & Hopkins, D. (1985). Research as a basis for teaching: Readings from the work of Lawrence Stenhouse. Oxford: Heineman.

Swedish Research Council. (2001). Ethical principles of research in humanistic and social

science. Retrieved from http://www.vr.se.

TRENDS. (2005). European universities implementing Bologna. European University Association.

TRENDS. (2010). A decade of change in European Higher Education. European University Association.

Twomey, A. (2004). Web-based teaching in nursing lessons from the literature. Nurse Education Today, 24, 452–458.

Winther Jørgensen, M. (2000). Diskursanalys som teori och metod [Discourse analysis as theory and method; in Swedish]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.